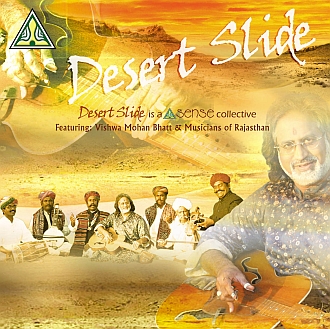

Desert Slide – a new chapter in Rajasthan’s age-old book of changes and musical adventures

6. 7. 2009 | Rubriky: Articles,CD reviews

[by Ken Hunt, London] Even by repute, people who have never been to Rajasthan and only ever saw photographs or artwork, view Rajasthan popularly as a region saturated with colour. In its Great Thar Desert, soil, sand and salt lakes offer a palette of yellows, browns and reds. In its deciduous woodlands dhok and dhak – the tree known as the ‘flame of the forest’ – provide the seasonal mosaics of the forest canopy and forest floor and then there is the vibrancy of bougainvillea everywhere whether on the highways or streets. In its street markets full of chillies, mangoes, bananas and spinach, Rajasthan offers an abundance of saturated colours – and watery contrasts. Then factor in whether through raga or folk dance or mela (festival) how musically Rajasthan is affected by what is all around when musicians play.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Even by repute, people who have never been to Rajasthan and only ever saw photographs or artwork, view Rajasthan popularly as a region saturated with colour. In its Great Thar Desert, soil, sand and salt lakes offer a palette of yellows, browns and reds. In its deciduous woodlands dhok and dhak – the tree known as the ‘flame of the forest’ – provide the seasonal mosaics of the forest canopy and forest floor and then there is the vibrancy of bougainvillea everywhere whether on the highways or streets. In its street markets full of chillies, mangoes, bananas and spinach, Rajasthan offers an abundance of saturated colours – and watery contrasts. Then factor in whether through raga or folk dance or mela (festival) how musically Rajasthan is affected by what is all around when musicians play.

An ornithological metaphor springs to mind when it comes to Rajasthan’s traditional music. Jaipur has been home for demoiselle cranes for time out of mind. Huge numbers hug the thermals over the Pink City (Jaipur), landing to strut their courtship and territorial stuff – a source of inspiration for Rajasthani dance. Yet Keoladeo, long the place where Siberian cranes overwintered, has seen the birds’ numbers decrease to next to nothing. What is increasingly happening in Rajasthan – without getting judgemental about the musicians, performers and dancers – is tradition is disappearing in the tourist heat haze. There is a buzz that folk culture is getting as defanged as the palaces’ dancing cobras.

The Desert Slide project bucks any such prevailing trends. A dynamic microcosm, it cross-fertilises two parallel yet different Rajasthani traditions. One is the world of Hindustani classicism that Mohan Vishwa Bhatt playing the Vishwa Mohan vina represents. The other brings together Rajasthan’s two main indigenous and hereditary clans of semi-professional or full-time professional music-makers, namely the Langas and Manganiars (or Manganihars). That commingling of traditions is interesting because it brings together hereditary Hindu and Muslim musicians to common purpose. As a concert and recording collaboration, Desert Slide represents something boldly different in Rajasthani music.

The opening song Helo mharo suno on Desert Slide reinforces the conjoining of traditions. It is a praise song for Baba Ramdev, who was soon revered both as a Hindu deity and an Islamic pir (saint) in Rajasthan. In many ways what is more interesting still than Baba Ramdev crossing that religious divide is him spanning the gulf of caste.

Desert Slide is designed to grab your attention and is the very personification of how musicians embrace vocal and instrumental folk and art music traditions – that business of music connecting rather than dividing.

Let’s dig deeper.

The opening devotional song Helo mharo suno (track 1) is kin to the bhajan form of Hindu hymnody. It is in praise of one of Rajasthan’s most revered Hindu deities and Islamic pirs (saints) of medieval times. Said to have lived from 1469 to 1575 in the Christian Era, Baba Ramdev is linked with the Pokaran district, some 110 km east of Jelsalmer in western Rajasthan and is often depicted on horseback. His worship crosses the Hindu-Muslim divide as well as crossing the caste line since his followers include caste Hindus and the casteless (Dalits or Untouchables) in modern-day Rajasthan and Gujarat – and even further afield into Madhya Pradesh and Sind on the Pakistani side of the border. Several Rajasthani melas (fairs or festivals) celebrate his memory. Helo mharo suno is rooted in râg Bageshri with a sprinkle of râg Shahana and appears in an 8-beat tâl (rhythm cycle). Its title can be rendered along the lines of ‘Hear me calling you’ or ‘Hear my entreaty’. The style of singing is designed to attract attention. And it works remarkably well.

Avalu thari aave, badilo ghar aave (track 2) is a song of separation, a woman’s plea to her beloved (badilo), asking him to come home (ghar). Vishwa Mohan Bhatt plays a theme, a rhythmic melodic hook of his own composition early in the piece to convey a sense of journeying, but the wit of his playing lies in slipping between the interstices of ‘ragadom’. The interpretation is based in râg Bhairav with a little trace of Kalingra, another morning râg, again in the same 8-beat tâl, keherwa or kaharwa as Helo mharo suno. The portrait painted uses filigree brushstrokes, impressionistically summoning the two râgs’ slight difference.

Avalu thari aave, badilo ghar aave (track 2) is a song of separation, a woman’s plea to her beloved (badilo), asking him to come home (ghar). Vishwa Mohan Bhatt plays a theme, a rhythmic melodic hook of his own composition early in the piece to convey a sense of journeying, but the wit of his playing lies in slipping between the interstices of ‘ragadom’. The interpretation is based in râg Bhairav with a little trace of Kalingra, another morning râg, again in the same 8-beat tâl, keherwa or kaharwa as Helo mharo suno. The portrait painted uses filigree brushstrokes, impressionistically summoning the two râgs’ slight difference.

Jhilmil barse meh (track 3) is a rainy season song. In Rajasthani ‘meh’ means rain, a word perhaps related to the Hindi ‘megh’ (cloud) – hence the monsoon season râg Megh. ‘Barse’ means ‘pouring’ in this context while ‘jhilmil’ indicates something tiny or small, so the line can be translated as ‘Droplets of rain are falling’. The song is based in Malhar, a monsoon season râg, and Des, a râg with a Malhar feel. It is, so to speak, Des with a wash of Malhar – as distinct from Des Malhar, another râg permutation. Again, like all the pieces on Desert Slide bar Kesariya balam, it is in keherwa – that 8-beat tâl.

All languages love onomatopoeia. Rajasthani is no exception. In track 4, Hichki (Hiccoughs) hinges on a local folk belief or superstition. When a person thinks of somebody from whom they are apart, the person he or she is missing is said to get the hiccups. The narrator has got the hiccups. In Rajasthan the râg it is set in is commonly called Bhairavi but it is actually truer to Kirvani, a râg originally associated with the South Indian heartland. Vishwa Mohan Bhatt’s alap or opening invocation is designed to set the mood or scene, creating an atmosphere suffused with sadness or melancholy and a pain and pangs of separation. It also has a romantic undertow strong enough to whip the listener off their feet.

All languages love onomatopoeia. Rajasthani is no exception. In track 4, Hichki (Hiccoughs) hinges on a local folk belief or superstition. When a person thinks of somebody from whom they are apart, the person he or she is missing is said to get the hiccups. The narrator has got the hiccups. In Rajasthan the râg it is set in is commonly called Bhairavi but it is actually truer to Kirvani, a râg originally associated with the South Indian heartland. Vishwa Mohan Bhatt’s alap or opening invocation is designed to set the mood or scene, creating an atmosphere suffused with sadness or melancholy and a pain and pangs of separation. It also has a romantic undertow strong enough to whip the listener off their feet.

Mhari menhdi ro rang (track5) (The colour of my henna) is set in Pahadi. Pahadi here is more like a dhun or folk air than a pure râg. Distinguishing it from a strict râg, Bhatt likes to dub it a “dhun Pahadi” – a folk air Pahadi. The programme’s instinctive mela sub-theme resurfaces here. In Rajasthan, but also elsewhere in the Indian subcontinent, menhdi or henna’s uses range from the cosmetic – it is a hair colorant used by men and women alike – to rites of passage. It is particularly associated with bridal adornment and is used to dye intricate patterns on celebrants’ hands. Henna is also associated with typically Rajasthani melas. One such is the monsoon-season Teej, the festival of swings, in the Hindu month of Shravana (August-time in the Christian calendar) which toasts Parvati’s union with Shiva and hence conjugal bliss. Another is Gangaur, Rajasthan’s defining 18-day mela that follows on the heels of Holi, the spring festival of colours, and a mela that, like Teej, is connected with the Goddess Parvati. Henna’s earthy browns and reds are the colours from which life – and symbolically, green – springs.

Kesariya balam (track 6) or Saffron Beloved – imagine the colour of kesar mangos – is another song of longing and separation. It is in the 6-beat dadra tâl and set in Mand, a râg borrowed from the folk music of Rajasthan. The lyrics welcome the listener to the person’s home or homeland. The singer sings of counting the days, counting off the days that they have been apart, on the finger joints of the outstretched palm. She has done this so frequently and for so long that the lines of the skin creases are wearing away.

Rajasthan’s vastness of bright light and vibrant colour is reflected in its folk arts and the land’s robust musical heritage. That intensity and the sheer size of the state determine that it is a land of extremes. It embraces the camel browns and kesar yellows of the Thar Desert on its western flank and – pointing east towards Uttar Pradesh – the grey plumage and black heads of demoiselle cranes soaring over the Pink City, descending to dance and inspire dancers.

Desert Slide reflects the excitement of its birthplace, its surroundings, its musical origins and the colours of Rajasthan. In its bridging of tradition, nothing like Desert Slide has ever been captured for posterity before and that is why Helo mharo suno in its invocation of Baba Ramdev is so perfect. He banished boundaries in Rajasthan. Maybe only a white writer would have dared make those connections.

(c) 2009 Ken Hunt and Vishwa Mohan Bhatt – http://www.vishwamohanbhatt.com/

Photographs Desert Slide (c) Sense World Music 2009, otherwise (c) 2009 Ken Hunt

Desert Slide Sense World Music 085 (2006)