All the world’s a screen – India’s film magazines

3. 3. 2009 | Rubriky: Articles,Feature

[by Ken Hunt, London] Wherever there is a successful film industry, like the penumbra to the klieg lights, film magazines will mushroom in order to feed people’s apparently insatiable appetite for news – planted or otherwise – and tittle-tattle. In the Anglophone world, from Picture Show (when ‘picture’ was the British Empire equivalent of ‘movie’) to the “Hollywood girls and gags!” of Movie Humor, cinema was well served from the silent era onwards. But India’s was, is and shall ever remain a special case.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Wherever there is a successful film industry, like the penumbra to the klieg lights, film magazines will mushroom in order to feed people’s apparently insatiable appetite for news – planted or otherwise – and tittle-tattle. In the Anglophone world, from Picture Show (when ‘picture’ was the British Empire equivalent of ‘movie’) to the “Hollywood girls and gags!” of Movie Humor, cinema was well served from the silent era onwards. But India’s was, is and shall ever remain a special case.

India has long been home to the world’s biggest film industry. Numerically and in terms of cultural penetration it outstrips Hollywood. Yet it is more than Bollywood. It includes the other major cine-woods – notably Kollywood (the Kolkata-based, Bengali equivalent), Mollywood (the cinema of Kerala in Malayalam), and Tollywood (the Chennai-based Tamil film industry).

Cinema spread like commercial wildfire in the Indian subcontinent from the 1890s, further to the brothers Auguste and Louis Lumiere showing their first reels in Bombay in July 1896. In a country in which illiteracy or near-illiteracy is still the norm in many states so many decades after Partition in 1947, silent film engaged and caught the public imagination with religious dramas, tales of the supernatural and slapstick, visual comedy. They transcended language and literacy skills. They glued the nation together and became a sort of neo-folklore. They re-defined and determined what popular culture meant. Film became the dominant cultural medium, displacing travelling companies and traditional theatre.

The arrival of film song

In 1931 India launched its own talkies. Ardeshir M. Irani’s adaptation of a Parsee drama Alam Ara (‘Light of the world’) narrowly became India’s first talkie. Irani gave the subcontinent its first filmi sangeet (‘film song’) singer in W. M. Khan. Importantly, he used the same device – song and music – that the peripatetic theatre companies had used and were still using. Alam Ara became a hit that travelled too. A hit in India could be a hit too in, for example, Ceylon and Burma. Just as later Bombay film industry movies were hits in other continents in ways that Hollywood could not be. Hollywood came to epitomise Amerika, its values, its cultural myopia and especially its foreign policies. Bollywood films were and remain both neutral and, in the main, escapist. They carry none of the neo-imperialistic baggage of Hollywood.

In 1931 India launched its own talkies. Ardeshir M. Irani’s adaptation of a Parsee drama Alam Ara (‘Light of the world’) narrowly became India’s first talkie. Irani gave the subcontinent its first filmi sangeet (‘film song’) singer in W. M. Khan. Importantly, he used the same device – song and music – that the peripatetic theatre companies had used and were still using. Alam Ara became a hit that travelled too. A hit in India could be a hit too in, for example, Ceylon and Burma. Just as later Bombay film industry movies were hits in other continents in ways that Hollywood could not be. Hollywood came to epitomise Amerika, its values, its cultural myopia and especially its foreign policies. Bollywood films were and remain both neutral and, in the main, escapist. They carry none of the neo-imperialistic baggage of Hollywood.

Song – filmi sangeet – was the magic elixir that cinema-goers gulped down. The unlettered with ‘compensatory’ oral skills left having learnt the catchiest songs on first pass or a close enough take on the song to sing what passed as it to friends and family. Where once silent cinema had used mythic and religious stories to attract audiences, music now was the new universal element. That and spectacle. Increasingly song ‘choreographed’ to lavish dance scenes may have dislocated and suspended the narrative flow but they made borderline hits hanging on a whim and a prayer box-office magic. One great song could launch a film into the financial stratosphere.

Cinema magazines

Cinema magazines

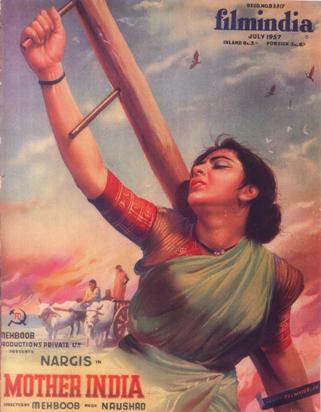

The film industry appreciated the power of words in print. People bought commemorative programmes for the film. These souvenirs had eye-grabbing cover graphics (often of the highest pictorial and printing standards), film credits and plot synopsis. They also had the printed lyrics to songs. These might be in Arabic or Shahmukti script and Devanagari for Urdu and Hindi readers respectively. The Mother India painting on the cover of Film India above is typical of the quality of these souvenir programmes’ artwork and shows why they were so prized.

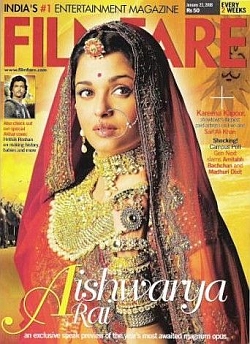

But from early on, the Indian film industry was also well served by film magazines. Bollywood may get the lion’s share of attention at home and abroad but cinema coverage has always extended (if an absolute like ‘always’ can ever be said or permitted) to regional cinema in regional languages. As a sociological phenomenon, India’s film magazines – and its letters pages – are the litmus test of the duality of conservatism and changing cultural and moral values. Yet whether discussing Dev Anand or Amitabh Bachchan, Helen or Aishwarya Rai, Guru Dutt or CyberIndian SFX, the coverage has stayed true to the lakh (100,000) and crore (100 lakh or 10,000,000) principles of success and failure.

As happened in Hollywood and Britain, Indian film magazines swiftly tapped into allure and celebrity, the stock-in-trade of today’s English-language titles like Cine Blitz, Filmfare (or Film Fare), g magazine, Movie and Stardust. With the arrival of the talkies in India, the hunger for titillation through alleged liaisons and rumoured off-screen snogs steadily grew. During the 1930s, publications like The Cinema, Film India (or filmindia) and Filmland dominated the English-speaking readership. Film India, the brainchild of Baburao Patel, was especially influential and Patel’s eviscerating reviews were greeted with grimace and glee in varying measures.

Between the 1950s and 1970s, a slew of new titles arrived. These included Film World, Filmfare, Madhuri, Screen, Stardust and Star and Style. Some survived. Most were gobbled up or went under. Following the Darwinian model though, when one went under other magazines appeared. Cinemaya (maya fittingly means ‘illusion’), launched in 1988, was but one that plugged a gap.

Between the 1950s and 1970s, a slew of new titles arrived. These included Film World, Filmfare, Madhuri, Screen, Stardust and Star and Style. Some survived. Most were gobbled up or went under. Following the Darwinian model though, when one went under other magazines appeared. Cinemaya (maya fittingly means ‘illusion’), launched in 1988, was but one that plugged a gap.

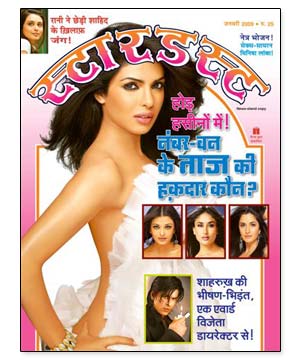

By the 1970s Stardust was arguably the market leader. Still, Filmfare had its prestigious awards that bolstered its reputation. The awards polarised and still polarise opinion – especially when a particular film, actor or song failed to scoop a particular award. Never underestimate controversy.

The Bombay-based Cine Blitz proved a particularly important title. Its launch issue in December 1974 rang bells like a sure-fire attention grabber. Prominent was a piece about flower-child Protima Bedi, later a gifted Orissi classical dancer. It came with photos of her streaking – a gesture of liberation and progressiveness unparalleled in denial-ridden, pseudo-moralistic India – on Bombay’s Juhu Beach. Of such circulation fillips are lakhs made.

Regionally based bilingual titles such as the English-Gujarati Ranjit Bulletin also emerged. They were, to home in on Gujarati, today’s Abhiyaan (roughly something between ‘work’ and ‘mission’) and its forerunners like Cinema Sansar (sansar, as a word, summons a serried bank of meanings including ‘home’ and ‘humanity’) and Moj Majah (‘Enjoyment’). Elsewhere in the subcontinent, print and online publications devoted to cinema have flowered. Malayalam has its Villinakshatram and Chithram and Kannada its Viggy and Chitraloka. Many have bilingual presences. There are many more examples beyond the Bollywood blogster hordes.

Regionally based bilingual titles such as the English-Gujarati Ranjit Bulletin also emerged. They were, to home in on Gujarati, today’s Abhiyaan (roughly something between ‘work’ and ‘mission’) and its forerunners like Cinema Sansar (sansar, as a word, summons a serried bank of meanings including ‘home’ and ‘humanity’) and Moj Majah (‘Enjoyment’). Elsewhere in the subcontinent, print and online publications devoted to cinema have flowered. Malayalam has its Villinakshatram and Chithram and Kannada its Viggy and Chitraloka. Many have bilingual presences. There are many more examples beyond the Bollywood blogster hordes.

The National Film Archive of India

First established in 1964, the National Film Archive of India (NFAI) is an organisation based in Pune with repositories in Bangalore, Kolkata and Thiruvananthapuram. Affiliated to the International Federation of Film Archives, the Pune site houses the ever-expanding national collection of film-related holdings with some 50,000 books and Central Board of Film Certification scripts, censorship records from the 1920s onwards and the main national archive of periodicals from the early 1930s onwards. Month in, month out, the NFAI acquires all the nation’s most important newspapers and periodicals on the subject – an indication of the commensal relationship between India’s press and the subcontinent’s film industry. Come the day its website expands, www.nfaipune.gov.in will become a useful tool internationally worthy of an international cultural phenomenon.

The paradox

The paradox

The major paradox is that, given the scale of music’s contribution to the industry, how little serious attention film music got historically and generally gets nowadays. Although, in the parlance of the time, “Miss Nurjehan” graced the cover of The Cinema as far back as 1931 – albeit, at the risk of blowing the relevance of the citation, as an actress rather than as a playback singer – the only publication that has consistently carried in-depth coverage of the Indian music scene is Screen, Mumbai’s weekly broadsheet-style paper. Through its succession of historian-minded journalists and name columnists such as Mohan Nadkarni reflecting on classical music from A. Narayana Iyer to Bhimsen Joshi and Rajiv Vijayakar doing detailed Q&A pieces about people like the Saawariya and Bhool Bhulaiyaa songstress Shreya Ghoshal, Screen has proved itself the magazine since the 1950s with, arguably, the keenest grasp of music in its Indian film context.

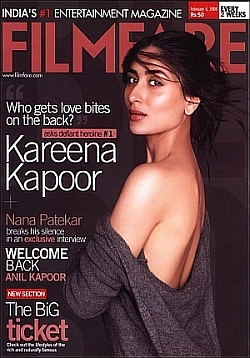

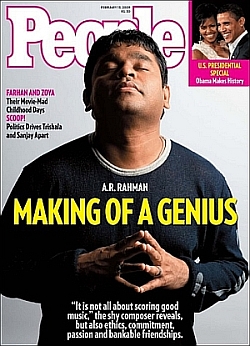

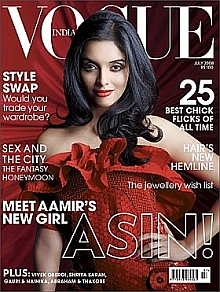

Indian cinema is big business. Just as Filmfare covets an Aishwarya Rai or Kareena Kapoor front cover and interview, mainstream titles like Vogue India or India Today want the sales boost an Aishwarya Rai cover brings. It is interesting that titles like People and Rolling Stone are covering Bollywood’s musical side now. Nowadays a musical phenomenon such as A.R. Rahman merits the full front cover treatment. Of course, Rahman comes trailing clouds of glory such as Bombay Dreams, Lord of the Rings and Slumdog Millionaire. (Tellingly none of them is Bollywood.) It is a far cry from Mojo commissioning me to write an article about Rahman and then retracting the commission after the interview was in the can because he was deemed a month later to be far too obscure to merit a single column inch.

Indian cinema is big business. Just as Filmfare covets an Aishwarya Rai or Kareena Kapoor front cover and interview, mainstream titles like Vogue India or India Today want the sales boost an Aishwarya Rai cover brings. It is interesting that titles like People and Rolling Stone are covering Bollywood’s musical side now. Nowadays a musical phenomenon such as A.R. Rahman merits the full front cover treatment. Of course, Rahman comes trailing clouds of glory such as Bombay Dreams, Lord of the Rings and Slumdog Millionaire. (Tellingly none of them is Bollywood.) It is a far cry from Mojo commissioning me to write an article about Rahman and then retracting the commission after the interview was in the can because he was deemed a month later to be far too obscure to merit a single column inch.

This leads us to that final question: that paradox. Given the importance of filmi sangeet in as the world’s most popular popular music form, where beyond the Lata Mangeshkar biographies are the magazines and books dedicated to India’s film song? Where is the detailed and in-depth coverage of this extraordinary popular music that out-performs rock, rap and reggae?

The good thing is that this feels curiously like being on the brink, like being witness to an exhilarating period. As happened, to give Western examples, when small magazines started running informative and informed, in-depth and passionate articles about rock or folk or punk as a reaction to the mainstream music press still treating those phenomena as mere youth crazes or passing fads. For, after all, when all is said, done and debated where would Indo-Pakistani film be today without filmi sangeet?

Ken Hunt is the author of the chapters on the Indian subcontinent’s music in the second and third editions of The Rough Guide to World Music. He compiled The Rough Guide to Asha Bhosle (World Music Network RGNET 1131 CD, 2003), The Rough Guide to Lata Mangeshkar (RGNET 1132 CD, 2004), The Rough Guide to Mohd. Rafi (RGNET 1133 CD, 2004) and The Rough Guide to Bollywood (RGNET1179CD, 2010).