Alton Kelley (1940-2008)

14. 6. 2008 | Rubriky: Articles,Lives

[by Ken Hunt, London] San Francisco’s graphic artist, painter and poster and collage artist, Alton Kelley died at his home in Petaluma, California on 1 June 2008 at the age of 67. It would be hard to over-estimate him as one of San Francisco’s foremost psychedelic artists and his impact on that scene’s rock music in visual and graphic terms. He was central to that blossoming of great handbill, poster and album art that people associate with San Francisco. Kelley blazed happy trails as part of the so-called Great Five – Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, Randy Tuten and Wes Wesley – with the signal difference that while the other four pursued their Muse largely through solitary activities, he shaped his unique vision usually in the glad company of Stanley ‘Mouse’ Miller – though Kelley and Griffin did collaborate on a poster advertising the triple bill of It’s A Beautiful Day, Deep Purple and Cold Blood at the Fillmore Auditorium in 1968.

[by Ken Hunt, London] San Francisco’s graphic artist, painter and poster and collage artist, Alton Kelley died at his home in Petaluma, California on 1 June 2008 at the age of 67. It would be hard to over-estimate him as one of San Francisco’s foremost psychedelic artists and his impact on that scene’s rock music in visual and graphic terms. He was central to that blossoming of great handbill, poster and album art that people associate with San Francisco. Kelley blazed happy trails as part of the so-called Great Five – Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, Randy Tuten and Wes Wesley – with the signal difference that while the other four pursued their Muse largely through solitary activities, he shaped his unique vision usually in the glad company of Stanley ‘Mouse’ Miller – though Kelley and Griffin did collaborate on a poster advertising the triple bill of It’s A Beautiful Day, Deep Purple and Cold Blood at the Fillmore Auditorium in 1968.

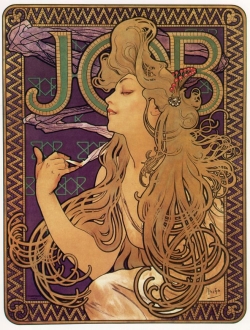

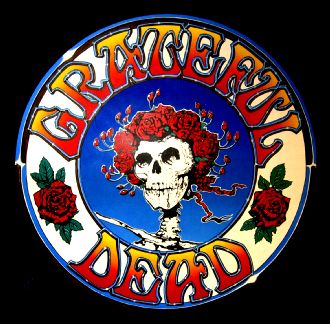

Collectively Mouse-Kelley, theirs was a linchpin team that would create Zeitgeist-capturing or timeless images for the San Francisco Bay Area’s finest – the likes of Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Big Brother & The Holding Company and many of the rest. Their images shouted San Francisco to a wider world. The posters and/or album covers that Mouse-Kelley created for Foreigner, Mickey Hart, Robert Hunter, Journey, Led Zeppelin, New Riders of the Purple Sage, the Rolling Stones, Styx and Wings became part of rock iconography. However just as the posters of the Ivančice, Moravian-born artist Alphonse Mucha (1860-1939) are associated with one artist in particular, the ‘divine’ actress Sarah Bernhard (1844-1923), so Mouse-Kelley came to be associated in particular with the Grateful Dead (1965-1995).

Kelley had headed west like so many others before him. The poetry talks of running out of road, braking before hitting the waters of the Pacific. But the reality had been crueller for generations. He settled in San Francisco in the mid 1960s. His actual birthplace was Houlton, Maine, where he was born on 17 June 1940. He did his proper growing up in Stratford and Bridgeport, Connecticut. Cars became a big deal and while still attending high school he fell under their automotive spell in the grand American way. As he would do till the end of his years, he would channel his obsession for cars into his artwork. He would do bespoke hot-rod-style paint jobs on them, he would showcase their images on posters and T-shirts, and he embraced the mythology of cars wholeheartedly, as much as his fellow Americans Hank Williams, Chuck Berry, Commander Cody & His Lost Planet Airmen and Bruce Springsteen did. It was the American car ‘n’ lost highway tradition in pictures. Plus and next, it was hardly coincidence that his longstanding collaborator, Mouse was similarly hooked on automotive excess, imagery and symbolism. That stuff calls and beckons down the tenses.

Kelley had headed west like so many others before him. The poetry talks of running out of road, braking before hitting the waters of the Pacific. But the reality had been crueller for generations. He settled in San Francisco in the mid 1960s. His actual birthplace was Houlton, Maine, where he was born on 17 June 1940. He did his proper growing up in Stratford and Bridgeport, Connecticut. Cars became a big deal and while still attending high school he fell under their automotive spell in the grand American way. As he would do till the end of his years, he would channel his obsession for cars into his artwork. He would do bespoke hot-rod-style paint jobs on them, he would showcase their images on posters and T-shirts, and he embraced the mythology of cars wholeheartedly, as much as his fellow Americans Hank Williams, Chuck Berry, Commander Cody & His Lost Planet Airmen and Bruce Springsteen did. It was the American car ‘n’ lost highway tradition in pictures. Plus and next, it was hardly coincidence that his longstanding collaborator, Mouse was similarly hooked on automotive excess, imagery and symbolism. That stuff calls and beckons down the tenses.

Kelley came out of an industrial design background. While he was never an academic, he knew his art and what moved him. He was a working-class pragmatist who had spent much of his life not in art adventures but in working as a mechanic and/or welder working on helicopters or road vehicles. He reached California in the 1960s, first settling in Los Angeles before relocating in San Francisco. His move coincided with San Francisco’s psychedelic explosion. Kelley was not especially precise about when he arrived in San Francisco, but his timing, whenever it was, was impeccable. The Vietnam War was in full spate and he needed something alternative in art terms. As he is quoted as saying in Mouse & Kelley (Paper Tiger, 1979), “Cars seemed as glamorous as washing machines.” He was being cute. He had bought into cars’ sleek-lined, finned and fendered iconography. He and Mouse would return to automotive imagery over and over again.

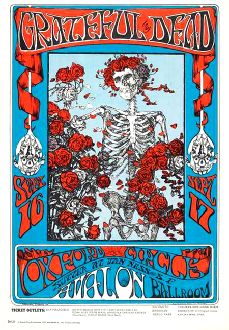

In 1965 he became a member of San Francisco’s hippie collective going under the name of the Family Dog. Amongst its number were Luria Castell, Chet Helms, Ellen Harmon and Jack Towle. And the collective had this bizarre notion to put on dance-concerts. Around 1965 the San Francisco Bay Area was becoming very different from elsewhere in the States. For one thing it was – and is – a walking city. Using public transport still carries no connotations of poverty, as elsewhere in citified USA. People walked or hopped on a trolley or a streetcar. And then continued walking. Haight’s telegraph poles were covered with theatre and concert posters. And, just like today, they had adverts of all sorts tacked to them. Only these posters and handbills tugged at the eyeballs in a new way. These were advertising the next Grateful Dead, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Big Brother or Jefferson Airplane gig. And if it was a Family Dog dance-concert poster, it was advertising the next the Avalon Ballroom show on Sutter.

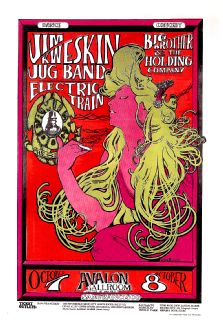

Kelley had the great, good fortune to bump into Mouse around this time. Mouse, born in Fresno, California on 10 October 1940, was likewise predisposed to the counterculture values of this new San Franciscan scene and the pictorial and graphic wonders of the past. They forged a new creative partnership. The partnership worked its influences relentlessly. Their posters were a hit-and-run artistic service. On their Howlin’ Wolf and Big Brother & The Holding Company poster at the Avalon in 1966 a slavering wolf roared. For the Dead and Sopwith Camel’s gig there that same year Frankenstein gazed out. The Mount Tamalpais Outdoor Theater gig with Joan Baez, Mimi Farina, the Grateful Dead and Quicksilver Messenger Service had Winnie The Pooh and his winsome little sidekick heading into the sunset, probably past the Sunset end of San Francisco, left of Golden Gate Park in other words, and onwards to the Pacific.

Kelley had the great, good fortune to bump into Mouse around this time. Mouse, born in Fresno, California on 10 October 1940, was likewise predisposed to the counterculture values of this new San Franciscan scene and the pictorial and graphic wonders of the past. They forged a new creative partnership. The partnership worked its influences relentlessly. Their posters were a hit-and-run artistic service. On their Howlin’ Wolf and Big Brother & The Holding Company poster at the Avalon in 1966 a slavering wolf roared. For the Dead and Sopwith Camel’s gig there that same year Frankenstein gazed out. The Mount Tamalpais Outdoor Theater gig with Joan Baez, Mimi Farina, the Grateful Dead and Quicksilver Messenger Service had Winnie The Pooh and his winsome little sidekick heading into the sunset, probably past the Sunset end of San Francisco, left of Golden Gate Park in other words, and onwards to the Pacific.

The Mouse-Kelley team proved as eclectic as the musicians themselves in their thieving. (The San Francisco Bay Area musicians stole beautifully.) What was grist to their mill? Well, old advertisements and mail order catalogues, images of Hollywood and Native Americans, science-fiction extraterrestrials and UFOs, sweet wrappers and robot visages, G-L-O-R-I-A Swanson and Mad magazine’s mascot-in-chief Alfred E. ‘What me worry?’ Neuman all figured. But from early on they snaffled the sensibilities of Belle Époque, Art Deco and Jugendstil materials. And since we are a Prague-based website, let’s be unambiguous: Alphonse Mucha must be mentioned. They gave Ol’ Mucha a new twist of psychedelicised life. ‘Girl with Green Hair’ advertised a 1966 Avalon Ballroom dance-concert by the Jim Kweskin Jug Band and Big Brother & The Holding Company. Out of the kindness of their hearts, an attractive woman whose original job in life was to sell Job cigarette papers was re-employed.

Poster art has an illustrious history but it is predominantly a commercial art. Just as Mucha had his champagne and Job cigarette papers, Kelley-Mouse had their images of hot rods and, er, Zig-zag cigarette papers. Theirs was definitely commercial art. Their 1973 Monster T-Shirt Catalog peddled clothing with images of bygone babes, dragsters, a jester holding a skull mask or stroking his chin, cosmic goofs and even rolling papers.

Poster art has an illustrious history but it is predominantly a commercial art. Just as Mucha had his champagne and Job cigarette papers, Kelley-Mouse had their images of hot rods and, er, Zig-zag cigarette papers. Theirs was definitely commercial art. Their 1973 Monster T-Shirt Catalog peddled clothing with images of bygone babes, dragsters, a jester holding a skull mask or stroking his chin, cosmic goofs and even rolling papers.

By 1966 they were branching out into album cover art with the Grateful Dead’s eponymous debut. It is a period piece, a journeyman collage without any of the flair of their later work but this was an era of scalpel and cow gum. It is drab beside their later silkscreen poster work or their plunging into Pantone’s new fluorescent colours territory.

The Mouse-Kelley team came to work extensively with the Dead, indeed went on the payroll as part of the band’s extended family, it was said. They contributed massively to the Dead’s image. Kelley’s adaptation of an Edmund Sullivan illustration in the 1859 edition of Edward Fitzgerald’s The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám was perhaps their most iconic contribution. If it had been a film it would have blazed like the icons in Andrei Rublev, Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1966 film. It depicted a skeleton with a skull crowned or wreathed – choose your symbology – with roses. It started as a 1966 concert image, became an album cover in 1971 (for, confusingly, another Grateful Dead, this time a double live album) and afterwards entered the Dead’s core iconography.

They would work with other Dead images. The dusty brown cover photograph of Workingman’s Dead (1970) was Kelley wiping the lens on his Brownie camera. American Beauty (1970) employed rose symbolism – American Beauty is a variety of rose – and the ambiguity of lettering (‘American Reality’ could also be read). The triple-LP Europe ‘72 (1972) went cartoon on its cover. Terrapin Station (1975) included a sly reference to a Fillmore Auditorium poster for a Turtles (and Oxford Circle) gig that Heinrich Kley and Wes Wilson had done in 1966. That was the thing about Alton Kelley. If you knew your art and music history, there was so much in those images to nod sagely in agreement to. But there was a lot more in the way of allusions that you knew you would have to crack later. That is the history and magic of art, with or without the oomph of psychotropic substances.

We thank the copyright holders for permission to use:

Girl with Green Hair (c) Mouse/Kelley 1966 for FD, Rhino Entertainment

Skeleton and roses image (c) Mouse/Kelley 1966 for FD, Rhino Entertainment

Grateful Dead logo (c) Mouse/Kelley