Howard Evans (1944-2006)

14. 3. 2011 | Rubriky: Articles,Lives

[by Ken Hunt, London] British folk music found a top drawer brass player, arranger and composer in Howard Evans. He had an utterly pragmatic, utterly professional attitude to music making and the musician’s life and from 1997, when he joined the Musicians Union’s London headquarters, as assistant general secretary for media he revealed that over and over again. He was totally pragmatic about his art and the first to drolly prick any bubbles of pretension about making music. He brought a wider knowledge and a greater diversity of musical experiences to bear on making music than any professional musician I ever met but he never got the slightest tan from the musical limelight.

[by Ken Hunt, London] British folk music found a top drawer brass player, arranger and composer in Howard Evans. He had an utterly pragmatic, utterly professional attitude to music making and the musician’s life and from 1997, when he joined the Musicians Union’s London headquarters, as assistant general secretary for media he revealed that over and over again. He was totally pragmatic about his art and the first to drolly prick any bubbles of pretension about making music. He brought a wider knowledge and a greater diversity of musical experiences to bear on making music than any professional musician I ever met but he never got the slightest tan from the musical limelight.

He mixed years of experience playing brass in military music contexts with the Welsh Guards, in pit orchestras, in London shows such as Cats, Starlight Express and Lou Reizner’s production of The Who’s Tommy and for sessions for the likes of the Star Wars soundtrack, Rick Wakeman, Emerson, Lake & Palmer Evans and the André Previn-era London Symphony Orchestra. Apart from the LSO, he played with the Royal Ballet, Welsh Opera and, most pertinently for his folk connections, with the National Theatre (NT) (as it was called before it got a ‘Royal’ appendage stuck at its front).

He mixed years of experience playing brass in military music contexts with the Welsh Guards, in pit orchestras, in London shows such as Cats, Starlight Express and Lou Reizner’s production of The Who’s Tommy and for sessions for the likes of the Star Wars soundtrack, Rick Wakeman, Emerson, Lake & Palmer Evans and the André Previn-era London Symphony Orchestra. Apart from the LSO, he played with the Royal Ballet, Welsh Opera and, most pertinently for his folk connections, with the National Theatre (NT) (as it was called before it got a ‘Royal’ appendage stuck at its front).

He brought this to bear when playing with Martin Carthy and John Kirkpatrick, Brass Monkey and the Home Service. Born in Chard, Somerset in England’s West Country on 29 February 1944, he died in North Cheam in Surrey on 17 March 2006. He first picked up a brass instrument (“baritone sax horn,” he told Owen Jones’ short-lived folk magazine Albion Sunrise, “it was actually a tenor sax horn”) when he was 10 and eventually graduated to cornet. At the age of 13 he passed an audition to play with the National Youth Brass Band. He left school aged 15. In 1961, after a couple of years of scratching a non-musical living, he responded to an advert in the UK magazine British Bandsman for experienced cornet players. The Welsh Guards recruited him on talent and because he father was Welsh. Nine years as a bandsman with the Welsh Guards followed and later drew on this experience with choice morsels such as Old Grenadier in Brass Monkey’s repertoire or the inclusion of Percy Grainger’s Lincolnshire Posy in the Home Service’s repertoire. They illuminated the British folk scene. He also did sessions for the likes of Leon Rosselson and Loudon Wainwright III. He just regarded himself as a musician, not a folk musician or any other musical subgenre.

Howard Evans could play anything brassy, whether trumpet, cornet, flugelhorn or, on one occasion in an NT production, alpenhorn. He was a total musician as happy analysing Miles Davis’ Sketches of Spain or Dave Brubeck’s ‘Take Five’ as a little Percy Grainger or something from The Who. He had managed to get a foot inside the NT pit in the 1970s with Tales From The Vienna Woods. Productions such as The Plough And The Stars and Sir Gawain & The Green Knight tumbled after, leading to the invitation to join Ashley Hutchings’ post-Rise Up Like The Sun Albion Band, then preparing for the Bill Bryden’s production of Lark Rise in the NT’s Cottesloe Theatre. The NT’s ‘Green Room’ was renowned for its conviviality. Out of one conversation came the offer for him to work with the guitarist and vocalist Martin Carthy and the free reed maestro and vocalist John Kirkpatrick. It seemed a good idea. The first fruits of their newly hatched partnership were him overdubbing trumpet on Jolly Tinker and Lovely Joan on Carthy’s Because It’s There (1979). By January 1980 they were out gigging as a three-piece which was when I first met him.

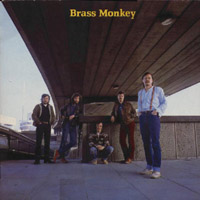

That trio grew and in January 1981 metamorphosed into a fresh elemental force eventually called Brass Monkey, an idiom open to various interpretations, as a quintet with Martin Brinsford playing sax, mouthorgan and percussion and Roger Williams trombone, occasionally tuba and euphonium. They stayed together, apart from a period in which Richard Cheetham occupied the trombone chair Williams rejoined. Their head-turning Brass Monkey (1983) (now combined with their second LP See How It Runs (1986) – derived from the Saxa Salt catchphrase – as The Complete Brass Monkey (1993)) contains a remarkable reworking of the incest ballad The Maid And The Palmer, one of the most daring and mesmerising performances ever committed to posterity or perdition. The combination of Evans, Williams and Brinsford playing together will be etched into anyone’s memory who saw them. They were that potent a force. Brass Monkey went on to make five albums with Sound & Rumour (1998), Going & Staying (2001) and Flame of Fire (2004). It was while touring with Brass Monkey that Evans fell ill. He was diagnosed as having cancer. We spoke afterwards and he confessed to an initial rush of ‘Why me?’ thoughts, soon eclipsed, typically, by a ‘Why not me?’ reflection.

That trio grew and in January 1981 metamorphosed into a fresh elemental force eventually called Brass Monkey, an idiom open to various interpretations, as a quintet with Martin Brinsford playing sax, mouthorgan and percussion and Roger Williams trombone, occasionally tuba and euphonium. They stayed together, apart from a period in which Richard Cheetham occupied the trombone chair Williams rejoined. Their head-turning Brass Monkey (1983) (now combined with their second LP See How It Runs (1986) – derived from the Saxa Salt catchphrase – as The Complete Brass Monkey (1993)) contains a remarkable reworking of the incest ballad The Maid And The Palmer, one of the most daring and mesmerising performances ever committed to posterity or perdition. The combination of Evans, Williams and Brinsford playing together will be etched into anyone’s memory who saw them. They were that potent a force. Brass Monkey went on to make five albums with Sound & Rumour (1998), Going & Staying (2001) and Flame of Fire (2004). It was while touring with Brass Monkey that Evans fell ill. He was diagnosed as having cancer. We spoke afterwards and he confessed to an initial rush of ‘Why me?’ thoughts, soon eclipsed, typically, by a ‘Why not me?’ reflection.

Working in the NT brought him into contact with an eleven-piece Albion Band offshoot rehearsed from November 1980 and March 1981 near the NT while working on The Passion. The tentatively titled First Eleven chrysalis included Evans and Kirkpatrick. The group that finally emerged, a mere septet, was the Home Service, England’s most forceful electrified folk group Fairport Convention and Steeleye Span. They created a never-before-heard sound live. Even if their debut Home Service (1984) failed to deliver the band’s power and majesty, it revealed the power of their songwriting and arranging. The Mysteries (1985) with Linda Thompson as guest vocalist was a marked improvement but still tied them to their NT sinecure. They broke free with their masterful Alright Jack (1986). Evans shaped the work mightily, suggesting Percy Grainger’s Lincolnshire Posy, a suite he had encountered with the Welsh Guards. In the mixing room a copy of John Bird’s biography of Grainger was a fixture, a touch I loved.

At the 1982 Cambridge Folk Festival, whilst sitting with the writers Richard Hoare and the John Platt, that West Coast man of many strings David Lindley first heard an act billed as the Martin Carthy Band. A couple of years later, he told me, “It was the most exciting, original thing I’d heard in ten years.” Their proper name was Brass Monkey. Nobody had ever combined voice, stringed and free reed instruments, percussion, reed and brass instruments like Brass Monkey before. Maybe nobody had ever imagined that combination in its blending of folk and wind bands. At Jackson Browne and David Lindley’s Theatre Royal concert in London on 27 March 2006, Lindley called Brass Monkey “one of my favourite bands of all time” and dedicated El Rayo-X to Howard Evans saying “This song is supposed to have horns in it. He’ll be playing.”

At the 1982 Cambridge Folk Festival, whilst sitting with the writers Richard Hoare and the John Platt, that West Coast man of many strings David Lindley first heard an act billed as the Martin Carthy Band. A couple of years later, he told me, “It was the most exciting, original thing I’d heard in ten years.” Their proper name was Brass Monkey. Nobody had ever combined voice, stringed and free reed instruments, percussion, reed and brass instruments like Brass Monkey before. Maybe nobody had ever imagined that combination in its blending of folk and wind bands. At Jackson Browne and David Lindley’s Theatre Royal concert in London on 27 March 2006, Lindley called Brass Monkey “one of my favourite bands of all time” and dedicated El Rayo-X to Howard Evans saying “This song is supposed to have horns in it. He’ll be playing.”

At Howard Evans’ packed ‘leaving do’, the remaining four Monkeys played him out with Old Grenadier, one of pieces he had brought to the band’s table at the beginning.

Very much in Howard Evans’ memory, Brass Monkey continues to perform. Paul Archibald, on trumpets, piccolo trumpet and cornets, debuted live in March 2009 at the Electric Theatre in Guildford, Surrey playing a repertoire that included material from Brass Monkey’s then-unreleased Head of Steam (2009).

The Home Service album sleeve image is © and courtesy of Fledg’ling Records. The album sleeves and images of Brass Monkey are © and courtesy of Topic Records. In the first photo by John Haxby they are L-R: Martin Brinsford, Martin Carthy (below), John Kirkpatrick (above), Roger Williams and Howard Evans. In the second they are Martin Carthy, Howards Evans, Martin Brinsford, John Kirkpatrick and Richard Cheetham.