India, despite it’s rich heritage, remains a white spot on the music map.

28. 9. 2024 | Rubriky: Articles,Interviews

[Petr Dorùžka, Krems, Austria] Music enterpreneur Ankur Malhotra explains: The reason is favoritism and classism. There are millions spent by billionaires on weddings rather than be used to support the musicians via grant systems.

[Petr Dorùžka, Krems, Austria] Music enterpreneur Ankur Malhotra explains: The reason is favoritism and classism. There are millions spent by billionaires on weddings rather than be used to support the musicians via grant systems.

Malhotra represents some of the best Indian folk and roots musicians who perform on major festivals worldwide. Barmer Boys play spiritual Hindi and Muslim songs from the Rajasthani desert. 77-year-old Lakha Khan is the last living sarangi violin master. His music ranges from ragas to Sufi chants and epic chants. Decades ago, the virtuoso violinist Yehudi Menuhin was one of the first Western supporters of Indian music. He declared that the dark and hypnotic tone of the sarangi is “the very soul of Indian feeling and thought”.

Indian music has been explored step by step by the West during the past 70 years. On his travels, Menuhin discovered two greats of classical music, Ali Akbar Khan and Ravi Shankar. He presented Khan in 1955 at the New York Museum of Modern Art. Shankar was touring in the West since 1956, in 1960 he gave a concert at the Prague Spring festival, and four years later at the Woodstock festival. Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan from Pakistan took qawwali sufi chants to Womad festival in 1985, thanks to Peter Gabriel.

However, music from the Indian subcontinent is still unknown in its full range. Yet, there are many cases when it flows to the West under favorable conditions. But when a Western listener travels to India as a cultural tourist, leftovers of colonial mentality reappear. Malhotra also explains this contradiction. The interview took place during the Glatt und Verkehrt festival in Krems on the Danube in Austria.

However, music from the Indian subcontinent is still unknown in its full range. Yet, there are many cases when it flows to the West under favorable conditions. But when a Western listener travels to India as a cultural tourist, leftovers of colonial mentality reappear. Malhotra also explains this contradiction. The interview took place during the Glatt und Verkehrt festival in Krems on the Danube in Austria.

How many professions do you have?

It depends on the time of day and what needs to be done. I am a mechanical engineer, I have an MBA degree, I have also worked in robotics, with aircraft engines, and children with dyslexia. But music has been more than a hobby for me since childhood. As a student, I made mixtapes for friends, later I became a radio host and DJ on American radio (WORT 89.9FM). I have worked in various capacities for my artists as producer, video director, sound engineer, photographer, mastering, cutting dub plates, websites, tour management, PR and marketing. Yes, I do have many professions.

So you started your career as an engineer?

I graduated from R.V. College of Engineering in Bangalore in South India, majoring in Mechanical Engineering. Then two years of software programming. And at the same time, I was making my way towards the music. I lived half in India, half in the US for the past two decades.

What kind of music did you prefere?

I was interested in blues, psychedelia. And Indian classical music too. When I was studying business in the US, I saw Bob Dylan and Neil Young for the first time. I started volunteered for a festival in Madison, Wisconsin. It was then that I noticed how many places in the world music comes from, but India was missing. That has no logic, because today it is the most populous country in the world. Our culture has a centuries-long history of music. I asked: can I do anything about it?

But Ravi Shankar played at Woodstock. George Harrison introduced Indian music to rock audiences. And then there was Shakti and other fusion bands.

That’s a tiny fraction. What about Indian folk music? Master players from the countryside also have a lot to offer. I was figuring out how to start, how to shape the identity of an artist. But first you need to record the music.

So you made field recordings? In Rajasthan, the birthplace of the European Roma?

Yes, that’s how I started working with some of the legendary folk masters from Rajasthan, also recorded their biographies, presented them at concerts. Musicians from all across Western Rajasthan and Kutch in Gujarat. By the way, Indian music is unimaginably diverse, and just in this relatively small zone of India (still larger than many Western European countries combined!) there was so much musical diversity to be found. Then we also have black communities, originally from East Africa, the Sidis based in Kutch.

Were their ancestors brought there as slaves?

Some were slaves, some came as traders, others as sailors, and as travelers. Exchange between India and East Africa has been going on for centuries.

Some were slaves, some came as traders, others as sailors, and as travelers. Exchange between India and East Africa has been going on for centuries.

For field recordings you need financial support. Could you apply for any government funding?

I took it as a labor of love. I was motivated by my love for music. There were some mentors who donated funds and some used equipment (Sony cassette recorder).

Have you been investing your savings?

I had minimal savings from my start up world and those all went into the business I co-founded (Amarrass Records). We struggled on extremely low budgets for a few years, but eventually I had to come up with some kind of sustainability plan.

How did you plan the next step? Licence field recordings to record labels, radio stations, academic archives?

Private stations in India are interested in commercial stuff, Bollywood. And as far as archives are concerned, my work was not meant to be an academic exercise. I wanted the music to bring joy to audiences. I wanted the music to create a lasting impression. I wanted the audiences to know the musicians name, know their music and their art. Those musicians knew nothing about distribution and show business, but they needed someone to get them out into the world. In Madison, Wisconsin, I was connected with one of the oldest community stations, WORT 89.9 FM, and in 2013, on my first US tour, we recorded in the studio with musicians. Later we got airplay and support from European stations like Funkhaus Europa, BBC, and more.

The 20th century had several milestones when Indian music came entered the Western world. Yehudi Menuhin introduced two giants of Indian classical music, Ravi Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan, to international audiences. George Harrison popularized the sitar. And in Britain, a modern version of the traditional bhangra music emerged, originally played in Punjab to celebrate the successfully harvested crops.

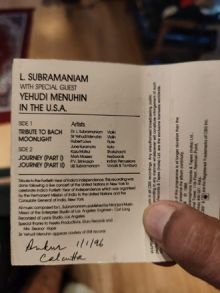

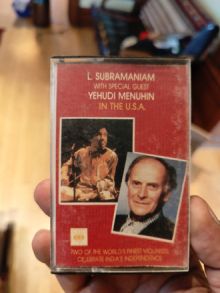

I would elaborate further. Menuhin, for example, played with the South Indian classical violinist L. Subramanian in the USSR in the early 1980s. When I was growing up in Delhi, I used to listen to an L. Subramanian cassette recording with the jazz violinist Stéphane Grappelli (Conversations). All these were key artists and opened the world’s ears to Indian music. Then, when modern bhangra emerged in the Indian diaspora in the 1980s, Indian music merged with hip hop.

How do Punjabi Indians really feel about British bhangra?

For example, Apache Indian, a British artist with Indian roots, had a big hit in India in the 1980s, which was made possible the multinational music television company MTV. But there are other connections. The Indian market was also penetrated by the Algerian rai singer Khaled. We played with Barmer Boys in Berlin (Wassermusik 2017) when Khaled was performing there. They performed their version of Khaled’s big hit Diddi, and he invited the Barmer Boys on stage. When Vieux Farka Touré (guitarist from Mali and son of the late Ali Farka Touré) came to India, he jammed with musicians from Rajasthan. Malian kora virtuoso, Madou Sidiki Diabaté, has performed with Lakha Khan. They could not talk to each other, but wonderful sound colors flowed from their instruments. Together they played 48 strings, 21 on kora, 27 on sarangi.

The kora, sounding like a European harp, is relatively familiar in the West, unlike the sarangi.

The sarangi, like the sitar and other Indian instruments, has three sets of strings: melodic, sympathetic, which provide additional color, and drone. The melodic ones are made of goat’s intestine, and the others are made of steel and bronze. It’s a notoriously difficult instrument to master and while the sound of the sarangi is omnipresent in a lot of classic Bollywood, the master musicians and luthiers who make this folk instruments are disappearing.

And that’s why the instrument is so hard to tune. When the temperature changes, does each of those strings go out of tune differently?

Yes, but at the same time, that is the beauty of the instrument. It’s sound has such a wide range of overtones. One single instrument creates amazing layers of sound.

Yes, but at the same time, that is the beauty of the instrument. It’s sound has such a wide range of overtones. One single instrument creates amazing layers of sound.

But, because of that complicated tuning, the sarangi as an accompanying instrument is gradually being displaced by Indian harmonium, and becoming the most endangered species in the world of Indian instruments?

Lahka Khan is the seventh generation of master players in his family, a recipient of the India’s highest honor, the Padma Shri Award. No wonder he looks down on the harmonium. You can play any note on the sarangi. It has no frets, whereas on the harmonium only notes corresponding to the keys can played. According to Lakha Khan, “you don’t even need any master skills to play the harmonium”. When I first met Lakha, he told me a story. His father told him before he died that if the sarangi continues to be played in the family, his name would be preserved in the memory of India. Each player is expanding his skills through his whole life and sacrifices everything for the instrument.

How do India-Pakistan relations work in culture?

There is no cross-border exchange, a completely absurd situation. The two countries are united by the same culture, but the governments do not allow the union, and music to be practiced. Meetings take place in third countries. Two years ago, we performed at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, and there were some beautiful moments. A master player from India and a qawwali singer from Pakistan were next to each other on the big stage.

Here in Austria, Lakha Khan performed this morning at an early concert as part of the festival. How did it go?

At 7 o’clock, he played morning ragas in the garden of the monastery. We named that concert the Awakening of the Gods, because unlike humans, they are not lazy and get up at sunrise. Specifically, we evoked the gods Rama, Krishna and Shiva. The second morning was a Sufi affair invoking the majesty of Allah’s creations. It was sold out. We did a similar concert at the Roskilde festival in Denmark.

If you are presenting Indian music to the world audiences, is there any chance for financial support?

In theory, this can work on two levels in India. In the philanthropic, private sector where you have patrons, and also on the state level. But neither works in music of my artists. For example, the Indian government offers programs where an artist gets a grant to perform in a concert to celebrate the Independence Day. So, the whole event is based on a routine, while the artist himself, the musical content, the creative part, are neglected by the officials. All that remains is to look for support through private initiatives.

On the other side, South Korea has a well-thought-out grant system which is more functional than in some European countries. The music of a country whose population is 30 times smaller than India’s is heard far more often at world festivals. Isn’t that an example Indian institutions should follow?

Korea is an exceptional example. It works similarly in Canada and in Scandinavia. There you can get a grant of 10,000 Euros. You will record an album with that money. Indians have a lot to learn, especially if they can spend hundreds of millions on a wedding. At the same time, such money could dramatically change the image of Indian music in the world.

Korea is an exceptional example. It works similarly in Canada and in Scandinavia. There you can get a grant of 10,000 Euros. You will record an album with that money. Indians have a lot to learn, especially if they can spend hundreds of millions on a wedding. At the same time, such money could dramatically change the image of Indian music in the world.

Hundreds of millions of rupees?

No, dollars. This is only possible because in India the dividing line between the government and corporate structures is somewhat blurred.

Thanks to corruption?

This is the first cause, the second is nepotism.

Nepotism, can you explain that?

That is the hidden structure. Who do you know, how well you get along with them, what contacts do you have. This determines your market value. And according to the list of acquaintances, your further destiny.

Which is strongly reminiscent of the unfortunate Indian caste system.

Exactly. A number of caste prejudices are so deeply rooted in society that they penetrate into the economic sphere as well. So, your place on the social ladder is all ruled by caste. And that also determines if you get invited to the party.

Have you had the opportunity to play at someone’s wedding with a band?

Yes, a couple of times in India. It happened in the diaspora, but also with the Barmer Boys in Denmark.

But a proper Indian wedding takes more than one day.

It depends on the region, sometimes even a week. They often invite more bands.

Can you put this to European perspective? In my country, it happens that a band from the Balkans cancels a concert at a festival when they receive a more lucrative wedding offer. Does that mean, that one wedding is equal to, say, five times a fee from a big festival like Roskilde?

Yes, depending on how wealthy the wedding party’s families are, the fees can be enormous sums.

Any example?

In July 2024, the son of multi-billionaire Ambani got married. The cost was 200 million dollars. Imagine someone like Rihanna among the guests. Her fee is 5 million. Mark Zuckerberg gave the newlyweds a private jet as a wedding present. Mukesh Ambani is the richest man in Asia. The status of the local airport was shifted to international. Just temporarily because of the wedding. That is the definition of nepotism. When you are a wealthy business executive in India, you can change the rules whenever it suits you.

When you play a wedding as a musician, you receive a fee according to the contract. The other part is the bills that the guests stick on the foreheads of musicians to play their favorite songs. How much does this make?

Sometimes more than the contract itself. They also attach banknotes to the musicians’ clothes, and make sure that everyone else sees it.

In India, you also have festivals whose program curators are experts from Europe. For foreigners who come to the festivals as cultural tourists, their names may be a guarantee of quality, but if you look at it from the point of view of an Indian, aren’t they missing something?

These festivals take place in historical forts, palaces, i.e. places that are not easily accessible to the ordinary Indian. A certain exclusivity is created, the event is expensive for the local listener. Besides tourists, these festivals are aimed at the local elite. I see it as segregation. Behind the scenes there are separate spaces for players of different importance. Organizers insist on their own prices, fees are often at the level of a pittance.

So, while the colonial mentality has died out in Europe, it does persist in the business European are doing in India?

Organizers circumvent the rules, considered as good manners in the industry. The musician’s manager also functions as a protection for the artist from unfair practices, but some of these presenters go directly to the artist and reduce the fee to minimum. The artist does not have the training to defend his interests. It’s a completely different approach than the festivals we play at here in Europe, which are aimed at the widest audience. Which is much more in line with my priorities. In this way, more permanent ties are created, important for the music community.

There is a large Indian diaspora in Britain and elsewhere. To what extent are those immigrants part of your audience?

It may sound surprising, but it is not. For example, in New York or Toronto, where the diaspora is very strong, we did not see many Indians in the audience.

In India, you have classical music, ghazal love songs considered as “semiclassical”, Bollywood music, spiritual chants. In Europe the line between classical and popular music is still rigid. How does it work in India?

Classical players look down on folk musicians. Lakha Khan, who comes from a folk music background, sees it this way: Yes, the classical players have to follow all these rules, but we have freedom. We can move across genres, we can play what a classic player is not allowed.

Would they invite him to a classical music festival in India?

Rather not. The Government of India has formalized this concept and made rules. There is an Indian Council for Cultural Relations and classical players get paid four times as much as folk musicians. The system is hierarchical, so even an inferior classical player is better off than a master folk musician.

A unique opportunity for artists to break out to international festivals is the annual Womex conference and showcase festival. You and the Barmer Boys were lucky to be selected but then cancelled. Why?

The reason was health problems. Lead singer Manga needed major heart surgery. He was only 49, like me. But when you work in India with rural artists, access to medical care and how to pay for it are highly complicated issues. And besides, these artists have no education. Manga is illiterate, his passport has a fingerprint instead of a signature. Science, medicine, that is a distant world for him. He escaped from that hospital and sought refuge in a Sufi shrine. There he recited prayers in the hope that he would be healed before the doctors.

(Unfortunately, Manga died in September 2024, 5 weeks after this interview).

In the case of Lakha Khan, does the term “last living master” have a different meaning in India than, ?say, among American bluesmen?

For one thing, yes. In India, so much work is still needed, so that the awareness of that music, its meaning, penetrates into public opinion, and into the institutions that can support it. For example, few people in India know who Lakha Khan is. But there are more people in the world today who have an idea about his talent.