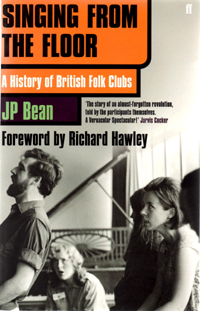

Singing From The Floor – A History of British Folk Clubs

19. 2. 2016 | Rubriky: Articles,Lives

J P Bean

J P Bean

Faber & Faber

ISBN 978-0-572-30545-2

[by Ken Hunt, London] Britain’s folk clubs must seem strange to anyone visiting them for the first time. They are an exceedingly British institution, only found on English, Northern Irish, Scottish and Welsh soil – or, allowing for poetic licence, on foreign soils as British forces’ transplants, such as RAF Luqa’s Malta Folk Club and the British Army on the Rhine. To interject a personal observation, the folk club equivalents in Eire, Germany, the Netherlands, Germany and the USA all have altogether different characters.

It was only in the second half of the 1950s that Britain’s folk clubs started and a coherent folk scene began coalescing. Ironically the English Folk Song & Dance Society had been frantically dance-orientated. Yet before the term ‘folk club’ was coined there were gatherings like Harry and Lesley ;Boardman’s ‘folk circle’ founded around 1954 in Manchester and Alex Eaton’s roughly contemporaneous Workers’ Music Association-inspired gatherings in Bradford. Often overlooked, there were university-based folk societies such as Cambridge’s St. Lawrence Folk Song Society, founded in 1950, and Oxford’s Heritage Society, operating by 1956. Aside from their own such as Stan Kelly and Rory McEwen they also booked occasional guests like Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Shirley Collins.

Arguably the first big stone flung into the pond was the establishment of Ballads & Blues in London. Hosted by Ewan MacColl, with strong support from Bert Lloyd, Isla Cameron, Fitzroy Coleman and Peggy Seeger, it met, most memorably, at the Princess Louise in High Holborn. Re-launched as a club in November 1957 after the Ballads & Blues ensemble returned from Moscow, the ensemble had lent its name to the club. It set so many standards. For example, Jimmie Macgregor, then teaching in Glasgow, would hitchhike from Scotland to London (over 700 miles there and back) to attend the club at weekends. By 1960 Robin Hall and Jimmie Macgregor’s duo would be the television face of folk.

Bearing in mind the importance of folk clubs to the vitality and longevity of the British folk scene it may seem peculiar that J P Bean’s absorbing oral history Singing From The Floor is the first major account devoted to the folk club institution. They were – and remain – the bedrock of the folk scene, the places where many people learned stagecraft and how to hone material or just to have a good evening out and a sing. Before camera-phones and YouTube folk clubs were where musicians unselfconsciously tweaked and road-tested material. J P Bean’s voyage began in 1966 when as a teenager he visited the folk club “above the Three Cranes pub” in his hometown, Sheffield.

You started researching this book in 1966 by going to your first club. What was your reason for going to one?

You started researching this book in 1966 by going to your first club. What was your reason for going to one?

I’d seen a bit on television. I’d seen Alex Campbell and Martin Carthy. I’d heard some pieces on the radio. I was only just 16 and I wanted to know more. I read a snippet in the local [Sheffield] paper about the Barley Mow folk club, so I went along and found this heaving, sweaty, oozy but cheerful Saturday night scene. And like I say in the intro it was like Christmas Eve every Saturday night. I saw people there, the impressions of whom would stay with me all these years.

More specifically, what attracted you?

What it was really that attracted me – it wasn’t just the Saturday night atmosphere or whatever – it was the characters. You know, there were some great characters in the folk clubs. There were people that made a big impression on you. People like Bob Davenport with the way he could hold the audience without any instrumental accompaniment all night long. Alex Campbell was a great character and a comedian but people like [Diz] Disley, Tony Capstick and Billy Connolly I would say I have a fondness for. They were wonderful times and I hope that comes across in the book.

When did you start interviewing people?

I started in April 2010. From the very first interviews with Louis Killen in Gateshead and Martin Carthy in Robin Hood’s Bay, from then to publication was almost exactly four years. The last year there wasn’t much happening because it was pre-production. I spent a good eighteen months roaming up and down the land just interviewing people, chasing them on the phone, getting numbers and networking. Then it slackened off as I started to put it together.

It was a wonderful social time. People welcomed you to their homes or you met them in pubs or you met them wherever. And heard the stories. I heard the stories of people who I’d only sat and marvelled at when I was young.

When looking back over that scene I know in my case I have semi-regrets I didn’t get to talk to certain people. Are there any people you would have dearly loved to have captured?

I would have loved to have interviewed Ewan MacColl. I would have liked to have interviewed Bert Jansch. I missed him by a very short span.

This is the dream. I’d have liked to have talked to Bob Dylan about London ’62/’63. And possibly Paul Simon. I wrote to Paul Simon’s management three times but didn’t get a reply. And I wrote to Dylan’s. But there are so many people who knew them at that time and presented a different angle or a different view on how they saw them – Dylan and Simon – that I think it really works out alright.

Did you ever go to any folk clubs outside of the British Isles?

Only Jersey [one of the Channel Islands between England and France]. And I don’t think that would count.

No, I didn’t and I would always have liked to have done. In those days when I was younger I would have loved to have gone to America or Canada. I didn’t get to American until ’94 and that was through doing the Joe Cocker book [Joe Cocker – The Authorised Biography, 1990, revised 2003].

Did you get any sense of impermanence at the end of the book you know, the way things have changed in the folk club scene?

How do you mean?

Well for instance, you talked about going along to the Barley Mow at the Three Cranes. Is the Three Cranes pub still there?

Yeah.

See, where I live [in southern England] pubs have just disappeared and most of the clubs were in pubs.

Most of the pubs in the Sheffield/South Yorkshire area where the folk clubs were held are still standing. They don’t all bear the ;same name. One of the big ones was the Highcliffe that is a very thriving gig now called the Greystones. The Highcliffe Folk Club was the first place in England where Billy Connolly, Barbara Dickson and John Martyn played, brought down by Hamish Imlach.

Years ago I went for a walk, as I used to do quite regularly, with Gill Cook [the doyen of Collet’s folk emporium in New Oxford Street] and I remember we did this walk – it was a ‘research pub crawl’. She talked about all the folk clubs in this little area of Soho in London. There were some in cellars and some in the top rooms of pubs. It was fascinating.

As you describe that this is exactly the reason I did Singing From The Floor. I wanted to get as many of those stories as I could. Gill Cook had died by that time. I was aware when Alex Campbell went that he must have had so many great stories because he’d played so many clubs, busked on the streets.

The one interview that sticks in my mind and it does pertain to Transatlanticness was sitting in a pub in Islington with Tom Paley. He was in his 80s at the time. He was talking about playing union hall gigs with Woody Guthrie and how Woody used to take him round to Leadbelly’s house on a Sunday afternoon. That was like touching history.

A lot of it was with a lot of people in England and Scotland but that with Tom Paley, for me, was quite amazing.

Julian Broadhead alias J P Bean died in late 2015. His obituary is here http://www.thestar.co.uk/news/sheffield-writer-j-p-bean-dies-aged-66-1-7560561#axzz3r5FvhJ4Z

Ken Hunt’s obituary of Gill Cook is here:

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/gill-cook-341453.html