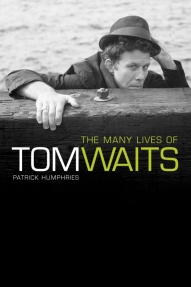

The Many Lives of Tom Waits

27. 11. 2007 | Rubriky: Articles,Book reviews

[by Ken Hunt, London] In a hoary old quote that pops up in Patrick Humphries’ The Many Lives of Tom Waits, Waits, that lovable whey-faced geezer in black with a pork-pie hat, quips, “Marcel Marceau gets more airplay than I do!” Things may have improved marginally in the meantime – Marceau dying in 2007 will have given Waits a chance to cut in – but Waits has proved tenacious when it comes to avoiding anything so vulgar as a whiffette of becoming a popular singing star. Waits is a man of many threads. He has regaled us with many mythologies, mostly hand-woven and threadbare enough for the unwary dupe to be taken in and buy him that figurative drink out of pity.

[by Ken Hunt, London] In a hoary old quote that pops up in Patrick Humphries’ The Many Lives of Tom Waits, Waits, that lovable whey-faced geezer in black with a pork-pie hat, quips, “Marcel Marceau gets more airplay than I do!” Things may have improved marginally in the meantime – Marceau dying in 2007 will have given Waits a chance to cut in – but Waits has proved tenacious when it comes to avoiding anything so vulgar as a whiffette of becoming a popular singing star. Waits is a man of many threads. He has regaled us with many mythologies, mostly hand-woven and threadbare enough for the unwary dupe to be taken in and buy him that figurative drink out of pity.

Suckers! To call Waits a singer-songwriter would be like damning him with faint praise. Buying into that singer-songwriter job description might be likened to buying eau de cologne or Viagra on the strength of a spam message. Or similarly responding to that plaintively lonely Russian lass or that Nigerian pet-lover-in-distress. Truth is, Waits is a fabulist. Verisimilitude is his stock in trade. That applies to his music and to his secondary career as a fellow who pops up in such films as The Two Jakes, The Fisher King and Bearskin: An Urban Fairytale.

Improbably, though in a nice way, The Many Lives of Tom Waits is his first major biography of the man. The London-based writer, Patrick Humphries is an old hand too, an established music writer whose subjects include Dylan, Hitchcock, Elton John, Pink Floyd, Paul Simon and Bruce Springsteen. Amongst his string of fine books, two are seminal – as in standard works. His Nick Drake (1997) and Richard Thompson: Strange Affair (1996) are true E.M.D. works. The expression is the title of one of the American mandolinist David Grisman’s finest, early breakthrough compositions. It stands for ‘Eat My Dust’. And every writer who writes about Nick Drake and Richard Thompson – and now Tom Waits – will ever have occasion to acknowledge – or avoid acknowledging – Humphries’ groundbreaking achievements.

Waits doesn’t peddle autobiographical or confessional stories-in-song in an L.A. Confidential manner. Like Waits, The Many Lives of Tom Waits does, however, allow Humphries to don the Chandleresque cap (alliteration wins out over fedora) when telling the tale. Waits is no Joni Mitchell, Jackson Browne or James Taylor. With Waits, you don’t get, in Humphries’ turn of phrase, “the open-heart surgery of Joni Mitchell or James Taylor”. Waits sends reports, sometimes Californian Chinese whispers, back from the Old Weird America. Or the Old Weird America in Waits’ Mind. Waits delivers fables. He tells tall tales. And, though everybody lies, Waits lies splendidly. His snappy one-liners are notable for their fragrance of insect repellent. Try, “I’ve always maintained that reality is for people who can’t face drugs.” (Did he filch the quip? Much like the lobotomy preference option one, does it matter? Allow Waits a few populist tendencies too.) He also protects his privacy, keeps his wife and partner-in-song Kathleen (née Brennan) and their family pretty well hid. He knows a thing or two about mystique. And did I mention meretriciousness? Humphries has wisely not set himself the task of unpicking verity from verisimilitude. That task would be messy. Like picking out just the red ones from a jar of M&Ms or Smarties while blindfold and allowed to use only your sense of taste. See? That’s how reading about Waits tinkers with a writer chap’s keying fingers.

The best part of the deal is that his songs and, heigh ho-ho, extraordinary renditions are like nobody else’s. Try, Waits’ dark-as-a-dungeon reappraisal of the 1938 Disney ditty Heigh Ho (The Dwarfs Marching Song) on Stay Awake and regurgitated on Orphans as evidence. Sure, you get a bit of this and a bit of that in his songs. Perhaps a glancing allusion to the dimly familiar or a bookworm’s regurgitation of something from some dog-eared almanac, like Waits’ spoken-word Army Ants with its Hammer House of Horror vibe on Orphans. A bit of banter, a prehensile-eared eavesdropping here, a lifted musical phrase or breaker’s yard metal-on-metal scream there. The stone-cold fact remains: his songs and attitudes are like nobody else’s. Surely, that’s why Iva Bittová from fair Brno town picked him for her wish-list concert. http://bittova.com/img/press/0704a.jpg (To be candid, I made it plain that we wanted a pair of complimentary tickets.)

The only disappointments with The Many Lives of. are bibliographical. The endnote references for each chapter have no cross-references in the bibliography. Mind you, what get at chapter’s end is the worst form of shorthand. To give random examples, how useless are “Brian Case, Melody Maker“, “Observer Music Maker” and “Timothy White”? Despite that inordinate irritation factor if you wish to get your head around the warped wonders that are Waits’, now you have two essential books to consult.

The first is Innocent When You Dream (2005). Edited by Mac Montandon, it is a gathering of collected journalism about, and interviews with Waits from the earliest days. The best stuff in it is like being locked in a Hall of Mirrors overnight and coming out with your imagination turned around, engaged and enslaved. The second book is Patrick Humphries’ The Many Lives of Tom Waits. Eat His Dust.

Patrick Humphries, The Many Lives of Tom Waits Omnibus Press ISBN 13:978-1-84449-585-6