CD reviews

[by Ken Hunt, London] When Joep Bor of the Rotterdam Conservatorium first conceived of a project that would take a selection of those “complex and abstract musical entities” known as ragas and present them in an accessible form, he had no idea how many years would flash by. By 1990 Bor was in partnership with the Monmouth, Welsh Border-based Nimbus label. What was little more than a pipe dream in 1984 eventually became The Raga Guide, a 4-CD, 196-page package, the product of a collaboration between traditional Indian musicians, the Rotterdam Conservatorium and Nimbus Records. It was launched at the High Commission of India’s Nehru Centre in London in April 2001.

[by Ken Hunt, London] When Joep Bor of the Rotterdam Conservatorium first conceived of a project that would take a selection of those “complex and abstract musical entities” known as ragas and present them in an accessible form, he had no idea how many years would flash by. By 1990 Bor was in partnership with the Monmouth, Welsh Border-based Nimbus label. What was little more than a pipe dream in 1984 eventually became The Raga Guide, a 4-CD, 196-page package, the product of a collaboration between traditional Indian musicians, the Rotterdam Conservatorium and Nimbus Records. It was launched at the High Commission of India’s Nehru Centre in London in April 2001.

Over that period team coalesced. Hariprasad Chaurasia, Buddhadev DasGupta, Shruti Sadolikar-Kalkar and Vidyadhar Vyas were the principal musicians, providing instrumental and vocal portraits of particular ragas – the full list is given below. The shapes in the smoke slowly took on tangible form and substance. But one of the major breakthroughs was the inclusion of song texts, where appropriate, provided in Devanāgarī script with English translations (although no transliterations for steering purposes).

Over that period team coalesced. Hariprasad Chaurasia, Buddhadev DasGupta, Shruti Sadolikar-Kalkar and Vidyadhar Vyas were the principal musicians, providing instrumental and vocal portraits of particular ragas – the full list is given below. The shapes in the smoke slowly took on tangible form and substance. But one of the major breakthroughs was the inclusion of song texts, where appropriate, provided in Devanāgarī script with English translations (although no transliterations for steering purposes).

At the turn of the century the Indian musicologist V.N. Bhatkhande (1860-1936) compiled a standard work on Hindustani, that is, Northern Indian ragas. Much has been published since but his raga manual remains an essential textbook. However, raga is, as Bor eloquently describes it, “a dynamic concept”. In subsequent books, one component was usually absent – the sound portrait. Add sound and microscopic detail, tone and expressiveness come alive. A unifying concept behind this raga manual for the next millennium became, as Robin Broadbank of Nimbus put it, to present “raga music from a performer’s perspective.”

Presenting each raga in a form that could be assimilated had been an early decision. As far back as 1984 Dilip Chanda Vedi had worked on brief raga outlines capturing the soul of the raga. The four musicians who finally accepted the mission impossible took over his work on his death. The first musician to begin recording these six-minute maximum raga sketches was the vocalist Shruti Sadolikar-Kalkar in 1991. The sarodist Buddhadev DasGupta, the flautist Hariprasad Chaurasia and the male vocalist Vidyadhar Vyas completed the line-up. One thing had been clear from the very beginning. This was to be a guide to Hindustani ragas, not a guide to Hindustani music making. Therefore, although instruments such as tabla and sarangi (a stringed instrument often used to shadow and accentuate a vocal line) feature in an accompanying guise, there is no attempt to have, say, sarangi, sitar or shehnai (a double-reeded, shawm-like instrument) as principal instruments.

“You have to make a choice,” Bor explained to me at the time of its launch. “You have to have very good musicians. I would have loved to have sarangi. I asked Ram Narayan, my teacher, but he just didn’t want to do it. At the end of the day the instruments are not that relevant. It’s the rāgs, it’s the interpretation of the rāgs which give a clear picture.”

This is an investment for every raga collection. Indispensible. If you see it, grab it.

The Raga Guide, Nimbus Nimbus NI 5536/9

Disc One

Disc One

1. Abhogi (Hariprasad Chaurasia)

2. Adana (Buddhadev DasGupta)

3. Ahir bhairav (Buddhadev DasGupta)

4. Alhaiya bilaval (Shruti Sadolikar-Katkar)

5. Asavari (Hariprasad Chaurasia)

6. Bageshri (Buddhadev DasGupta)

7. Bahar (Buddhadev DasGupta)

8. Basant (Hariprasad Chaurasia)

9. Bhairav (Hariprasad Chaurasia)

10. Bhairavi (Hariprasad Chaurasia)

11. Bhatiyar (Shruti Sadolikar-Katkar)

12. Bhimpalasi (Shruti Sadolikar-Katkar)

13. Bhupal todi (Hariprasad Chaurasia)

14. Bhupali (Hariprasad Chaurasia)

15. Bibhas (Vidyadhar Vyas)

16. Bihag (Buddhadev DasGupta)

17. Bilaskhani todi (Hariprasad Chaurasia)

18. Brindabani sarang (Buddhadev DasGupta)

Disc Two

1. Chandrakauns (Vidyadhar Vyas)

2. Chayanat (Buddhadev DasGupta)

3. Darbari kanada (Buddhadev DasGupta)

4. Desh (Hariprasad Chaurasia)

5. Deshi (Shruti Sadolikar-Katkar)

6. Dhani (Shruti Sadolikar-Katkar)

7. Durga (Shruti Sadolikar-Katkar)

8. Gaud malhar (Buddhadev DasGupta)

9. Gaud sarang (Shruti Sadolikar-Katkar)

10. Gorakh kalyan (Vidyadhar Vyas)

11. Gujari todi (Shruti Sadolikar-Katkar)

12. Gunakri (Vidyadhar Vyas)

13. Hamir (Buddhadev DasGupta)

14. Hansadhvani (Vidyadhar Vyas)

15. Hindol (Vidyadhar Vyas)

16. Jaijaivanti (Buddhadev DasGupta)

17. Jaunpuri (Buddhadev DasGupta)

18. Jhinjhoti (Buddhadev DasGupta)

Disc Three

1. Jog (Buddhadev DasGupta)

2. Jogiya (Hariprasad Chaurasia)

3. Kafi (Hariprasad Chaurasia)

4. Kamod (Buddhadev DasGupta)

5. Kedar (Buddhadev DasGupta)

6. Khamaj (Buddhadev DasGupta)

7. Kirvani (Hariprasad Chaurasia)

8. Lalit (Hariprasad Chaurasia)

9. Madhuvanti (Shruti Sadolikar-Katkar)

10. Malkauns (Hariprasad Chaurasia)

11. Manj khamaj (Hariprasad Chaurasia)

12. Maru bihag (Shruti Sadolikar-Katkar)

13. Marva (Vidyadhar Vyas)

14. Megh (Vidyadhar Vyas)

15. Miyan ki malhar (Vidyadhar Vyas)

16. Miyan ki todi (Vidyadhar Vyas)

17. Multani (Shruti Sadolikar-Katkar)

18. Nayaki kanada (Shruti Sadolikar-Katkar)

19. Patdip (Shruti Sadolikar-Katkar)

20. Pilu (Hariprasad Chaurasia)

Disc Four

1. Puriya (Vidyadhar Vyas)

2. Puriya dhanashri (Hariprasad Chaurasia)

3. Puriya kalyan (Hariprasad Chaurasia)

4. Purvi (Vidyadhar Vyas)

5. Rageshri (Buddhadev DasGupta)

6. Ramkali (Shruti Sadolikar-Katkar)

7. Shahana (Buddhadev DasGupta)

8. Shankara (Vidyadhar Vyas)

9. Shri (Vidyadhar Vyas)

10. Shuddh kalyan (Buddhadev DasGupta)

11. Shuddh sarang (Shruti Sadolikar-Katkar)

12. Shyam kalyan (Buddhadev DasGupta)

13. Sindhura (Buddhadev DasGupta)

14. Sohini (Vidyadhar Vyas)

15. Sur malhar (Buddhadev DasGupta)

16. Tilak kamod (Shruti Sadolikar-Katkar)

17. Tilang (Shruti Sadolikar-Katkar)

18. Yaman (Shruti Sadolikar-Katkar)

30. 5. 2011 |

read more...

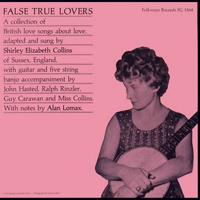

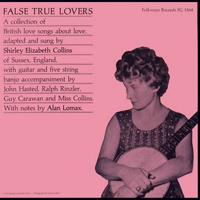

[by Ken Hunt, London] This concluding section departs from the previous structure. In this coda Shirley Collins compares then and now. She recollects what it was like starting out for her, with the recording of her first two LPs Sweet England (1959) and False True Lovers (1960) back-to-back in 1958. With Alan Lomax and Peter Kennedy presiding, she cut the tracks for those two records over two days in a house in the north London residential district of Belsize Park. She reflects on what is happening now, especially her concerns about fast-tracked success and its disadvantages.

[by Ken Hunt, London] This concluding section departs from the previous structure. In this coda Shirley Collins compares then and now. She recollects what it was like starting out for her, with the recording of her first two LPs Sweet England (1959) and False True Lovers (1960) back-to-back in 1958. With Alan Lomax and Peter Kennedy presiding, she cut the tracks for those two records over two days in a house in the north London residential district of Belsize Park. She reflects on what is happening now, especially her concerns about fast-tracked success and its disadvantages.

“I think it was quite spontaneous, a lot of it. Those two albums were recorded in two days. Everything was probably just done once, possibly twice if I made a great mistake. I just made up the next song as it came to it. At that time I was very naïve and I hadn’t been recorded like that before. In a way it was like a field recording, although done indoors in a studio. I was just singing the songs as they came up. Some of them had to be more thought about because other people were accompanying me on them. I don’t think we thought in advance because I know when all the recordings were made they were then divided up into the Folkways tracks and the Argo English choices. It wasn’t pre-planned. There was not that degree of sophistication or forethought then. It was quite spontaneous.

“I think it was quite spontaneous, a lot of it. Those two albums were recorded in two days. Everything was probably just done once, possibly twice if I made a great mistake. I just made up the next song as it came to it. At that time I was very naïve and I hadn’t been recorded like that before. In a way it was like a field recording, although done indoors in a studio. I was just singing the songs as they came up. Some of them had to be more thought about because other people were accompanying me on them. I don’t think we thought in advance because I know when all the recordings were made they were then divided up into the Folkways tracks and the Argo English choices. It wasn’t pre-planned. There was not that degree of sophistication or forethought then. It was quite spontaneous.

“None of us was used to recording anyway. We weren’t used to using microphones. I think you were always very nervous when you were being recorded as well. I remember feeling quite scared of the whole procedure.

“Nowadays you can record in your own kitchen or front room. Anyone can do it. I think anyone reading about how nervous one would be about doing it, would think, ‘Nah, it’s easy.’ It wasn’t then and I was recording for two rather important people. They were very encouraging. When I listen back to it, there really were some tracks on there that were quite lovely. And some that are quite dreadful; the songs aren’t worth being recorded. But it was typical of my repertoire at the time and typical of what I’d learned from home, so it was an honest record.”

If you were soaking up a song then, assimilating it and making it something of your own, if you like, what sort of length of time would that process have taken for you in those days? The reason I ask is I get the feeling with a number of singers nowadays that they are too quick off the mark recording songs. They’re not under the skin of the song.

If you were soaking up a song then, assimilating it and making it something of your own, if you like, what sort of length of time would that process have taken for you in those days? The reason I ask is I get the feeling with a number of singers nowadays that they are too quick off the mark recording songs. They’re not under the skin of the song.

“To be fair, I think that’s pretty much me for my first two. I wasn’t ready. They were too early. The songs weren’t good enough really. A great many of them were trivial and when I look back at them now I do cringe. But I think the difference between me then is that we didn’t have all the information behind us that the singers today should have. If they express an interest in traditional song, they should be prepared to listen to the traditional singers.

“I think you’re right. I think a lot of them are recording too soon. It’s understandable because if you want to make a career of singing you want to get going fairly quickly. Because they receive so much praise for their recording – they’re either the Best New Album of the Year or the Best Songwriter, Best Song or Best Folksinger – they’ve got to come up with the Best every year. You got so many Bests out there that it’s difficult to pick out the Best now. Not enough of them are listening to enough of the traditional singers that they should be listening to. You’ve got to listen to your Harry Coxs, your Phoebe Smiths, your Caroline Hughes, your Harry Uptons and your Coppers; you’ve just got to. How can you be a singer of traditional song if you haven’t formed any basis in the real thing and you’re acquiring songs the easy way from what the Revival singers were singing? And some of the Revival singers weren’t picking up from proper sources either, you know, from the best of the singers.

“So, in some cases the new singers are picking up ‘double-poor’: they’re not learning from the best. They’re doing it the easy way. There’s not enough hard work in there. They can play instruments like mad. They’re very good instrumentalists. But they’re not listening to the songs: they’re listening to themselves singing the songs. It’s so apparent when you listen to: they want to sound like either Sandy Denny or Kate Rusby. Sandy wasn’t a traditional singer. Wonderful singer, wonderful songwriter and great in that genre but not in folk music. Half the girls are singing like children, like little girls whispering into the microphone. The music is more robust than that. Even though a lot of the songs are tender and romantic, there’s still a wonderful robustness about them. Melancholy yes, but there’s still strength in there too. That seems to be missing from a lot of the modern performances. It’s what I feel.”

For more information go to www.shirleycollins.co.uk

For information about the discographical output and song material of Shirley Collins, Martin Carthy, Anne Briggs, Nic Jones and their kind, set aside a couple of hours to browse Reinhard Zierke’s labour of love and folk disquisition. Begin with Shirley at: www.informatik.uni-hamburg.de/~zierke/shirley.collins/index.html

Small print

The copyright of all other images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers. Unless otherwise stated, all interview material is original and copyright Ken Hunt.

25. 4. 2011 |

read more...

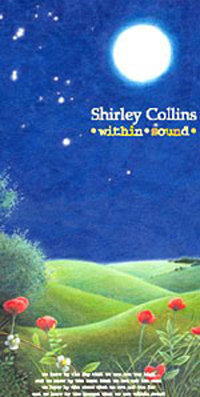

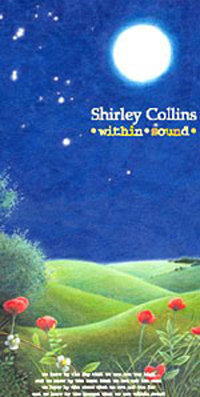

[by Ken Hunt, London] In this second part we pick up the story of the out-of-print classic retrospective Within Sound at a point after the 1970 masterpiece Love, Death & The Lady (1970).

[by Ken Hunt, London] In this second part we pick up the story of the out-of-print classic retrospective Within Sound at a point after the 1970 masterpiece Love, Death & The Lady (1970).

Despite everything in the years from 1955, when Shirley Collins had first appeared on record, to 1970 , there was no grand plan behind the continually shape-shifting projects that she was delivering. “I have to say,” she explains. “it ‘happened’ rather than it was planned in advance that one would do something different the whole time. Things did evolve. It was the discoveries. It was those fortunate meetings. It was my own interests in the sorts of music I liked listening to – Early Music, for example – that led me into these other things. In a way it did just grow. It wasn’t planned but it wasn’t willy-nilly. There was obviously a great deal of thought involved with each record once we decided to do the recording we were doing. I think it’s possibly because my personal life and my singing life were so bound up that whatever was going on in my life was reflected in the records as well. The influences, the things that were happening, the people I met as I went along… It’s all rather fortunate the way things happened. Like finding the Early Musicians in Musica Reservata and meeting David Munrow. But then, I suppose, it was having the wit to think that this and that would work together. With part of the early stuff it was John Marshall who thought that we could do it; it was Dolly who wrote the stuff and made it happen with her arrangements; and it was my ear and my own inclinations to do the best for the music.

Despite everything in the years from 1955, when Shirley Collins had first appeared on record, to 1970 , there was no grand plan behind the continually shape-shifting projects that she was delivering. “I have to say,” she explains. “it ‘happened’ rather than it was planned in advance that one would do something different the whole time. Things did evolve. It was the discoveries. It was those fortunate meetings. It was my own interests in the sorts of music I liked listening to – Early Music, for example – that led me into these other things. In a way it did just grow. It wasn’t planned but it wasn’t willy-nilly. There was obviously a great deal of thought involved with each record once we decided to do the recording we were doing. I think it’s possibly because my personal life and my singing life were so bound up that whatever was going on in my life was reflected in the records as well. The influences, the things that were happening, the people I met as I went along… It’s all rather fortunate the way things happened. Like finding the Early Musicians in Musica Reservata and meeting David Munrow. But then, I suppose, it was having the wit to think that this and that would work together. With part of the early stuff it was John Marshall who thought that we could do it; it was Dolly who wrote the stuff and made it happen with her arrangements; and it was my ear and my own inclinations to do the best for the music.

“In a way it harks back to what Alan always believed. Alan Lomax always believed that you put the best at the disposal of the people you were recording. He went for the best: the best technical quality you could get, the best recording equipment – and it was being improved the whole time. He always had to do the best for the people that he was recording. And I always felt that I had to do the best for the music. The best was, in many cases, to get a perfect accompaniment. Or if not perfect, an appropriate accompaniment for this lovely music that had been neglected for so long. I was fortunate to have a sister that could write it, and people around me that were encouraging. God knows, it didn’t get a lot of encouragement but there were key people!”

She volunteers their names without prompting. “I was fortunate to meet Lomax in the first place. John Marshall was another. He supported and encouraged me, and was always trying to find other ways of doing things – although they were tiresome at times as well. He was always willing and open to try things. I was fortunate later to meet Ashley. I was fortunate to have David Tibet come on the scene; he put out the first compilation of the Topic stuff. I was incredibly fortunate to have David Suff as a champion. I was absolutely blessed with these keen figures but then I also think they were also blessed with me.”

She volunteers their names without prompting. “I was fortunate to meet Lomax in the first place. John Marshall was another. He supported and encouraged me, and was always trying to find other ways of doing things – although they were tiresome at times as well. He was always willing and open to try things. I was fortunate later to meet Ashley. I was fortunate to have David Tibet come on the scene; he put out the first compilation of the Topic stuff. I was incredibly fortunate to have David Suff as a champion. I was absolutely blessed with these keen figures but then I also think they were also blessed with me.”

Recovering from a small fit of the giggles, she continues, “I’ve stopped being so modest nowadays because when I listen to the stuff I know it’s so good. I’m not going to sit back and pretend that it’s not now.”

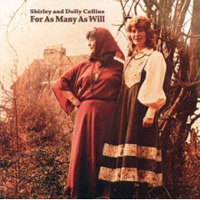

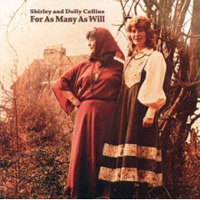

Part of the problem to do with her phasing out performing in public was a loss of confidence. In 1978 Topic released For As Many As Will, co-credited to her sister Dolly. Two years later on an Australian tour in early 1980, a double-hander with Peter Bellamy (formerly of the Young Tradition), she plagued herself with doubts – and self-inflicted doubts are amongst the worst . It had further repercussions for her singing. She remembers Australia as “being a terrifying ordeal because I didn’t have Dolly and I was losing my voice. It was part of this slow process of everything going and the more I did the more afraid I became. The Sydney Opera House was terrifying. When I listened to Come, My Love it was absolutely gorgeous. There was Dolly’s wonderful arrangement played with such bravura on the harpsichord by Winsome Evans that I thought, ‘You were all right, you could have kept on doing this, Shirl!’ But I didn’t hear this at the time. I wasn’t aware at the time that it was more than OK. I let myself believe that I was no good anymore. I loved English music and I wanted to be a singer of English songs. However hard it got, I never gave in. Until things got too impossible for me to be able to sing, that is. By that time, I’d already virtually done it really, I think against all the odds. I hoodwinked myself. Or perhaps I punished myself.”

Part of the problem to do with her phasing out performing in public was a loss of confidence. In 1978 Topic released For As Many As Will, co-credited to her sister Dolly. Two years later on an Australian tour in early 1980, a double-hander with Peter Bellamy (formerly of the Young Tradition), she plagued herself with doubts – and self-inflicted doubts are amongst the worst . It had further repercussions for her singing. She remembers Australia as “being a terrifying ordeal because I didn’t have Dolly and I was losing my voice. It was part of this slow process of everything going and the more I did the more afraid I became. The Sydney Opera House was terrifying. When I listened to Come, My Love it was absolutely gorgeous. There was Dolly’s wonderful arrangement played with such bravura on the harpsichord by Winsome Evans that I thought, ‘You were all right, you could have kept on doing this, Shirl!’ But I didn’t hear this at the time. I wasn’t aware at the time that it was more than OK. I let myself believe that I was no good anymore. I loved English music and I wanted to be a singer of English songs. However hard it got, I never gave in. Until things got too impossible for me to be able to sing, that is. By that time, I’d already virtually done it really, I think against all the odds. I hoodwinked myself. Or perhaps I punished myself.”

Going through the possible material for inclusion on Within Sound no longer involved breast- or brow-beating. The passage of the years had taught her the lesson not to judge herself as harshly as once she had. “There were certain things, like The False True Love that I’d recorded twice in my life, where I thought how brave a performance it was when I listened to it. That was the actual word. I hold one note and it just goes on. I was always in love or suffering. I think it has the essence of young, unrequited love in it. I thought, ‘God, that’s a brave performance!'”

This process of rediscovery threw up several insights too. “There are other things that you listen to – Poor Murdered Woman, which I think is one of the great tracks – which have great passion in them. It’s not so passionate that it’s dramatised. The passion is within the song itself. It’s a very restrained sort of passion. When I hear Poor Murdered Woman I think, that’s good. There are so many funny things too. Like, when you listen to Fare Thee Well, My Dearest Dear there’s Ashley’s bass louder than my voice. And I think that’s fairly typical. It makes me laugh but I had to put it on the boxed set because that’s such an important song to me and Harriet Verrall of Monksgate was such an important singer to me.”

With Within Sound surprises came in other packages too. One of the pieces that rings so sonorously down the years is the unearthing of Whitsun Dance. Unlike the ‘big band’ rendition from the finished Anthems In Eden (1969), on the boxed set she sings it alone with her sister accompanying on piano. Adding an insight into the creativity, it wafts in the refreshing tang of something familiar yet somehow unfamiliar. “That was obviously a trial recording of the piece. I didn’t know I had it. It came from the cupboard under the stairs. I got a box of tapes and we kept looking and looking. There was this thing that said Whitsun Dance. I thought it was bound to be an Anthems track. It was recorded in the studio, I don’t remember for certain, a day or so before. It is lovely. I was so thrilled when I heard it because it has a different quality and a slightly different lift to the tune. I hadn’t realised what I’d done. I was so thrilled by that little discovery. It’s only a slight difference but it’s a huge difference.”

With Within Sound surprises came in other packages too. One of the pieces that rings so sonorously down the years is the unearthing of Whitsun Dance. Unlike the ‘big band’ rendition from the finished Anthems In Eden (1969), on the boxed set she sings it alone with her sister accompanying on piano. Adding an insight into the creativity, it wafts in the refreshing tang of something familiar yet somehow unfamiliar. “That was obviously a trial recording of the piece. I didn’t know I had it. It came from the cupboard under the stairs. I got a box of tapes and we kept looking and looking. There was this thing that said Whitsun Dance. I thought it was bound to be an Anthems track. It was recorded in the studio, I don’t remember for certain, a day or so before. It is lovely. I was so thrilled when I heard it because it has a different quality and a slightly different lift to the tune. I hadn’t realised what I’d done. I was so thrilled by that little discovery. It’s only a slight difference but it’s a huge difference.”

What emerges over the course of Within Sound is the distillation of something uniquely English. Folksong isn’t everybody’s cup of tea – nothing is, thank goodness – but some of that is because too many people have come to the table with their minds made up about singers with cupped hand over the ear. (Far from being folk’s exclusive domain or folly, it is a technique used in voice projection round the globe.) Naturally, folksong must have had its moments of Moon-in-Junery but folk music’s oral process is an extremely efficient way of disposing of banality as well as preserving the stuff that touches the soul. After all, a shit song need not be a shit song forever; it can be relegated to the antiquarian’s back pages and quietly parked. It’s the good stuff that we remember and that is what we need to remember.

With Within Sound, part of England’s rich folk tradition began to receive the attention it deserves.

A coda

A coda

Harriet Verrall, it should be explained, was the original source of Poor Murdered Woman on Shirley Collins and the Albion Country Band’s No Roses (1971) and the well-known tune to Our Captain Cried All Hands, a piece of music that Ralph Vaughan Williams re-christened Monksgate when setting John Bunyan’s rousing school assembly ‘favourite’, He Who Would Valiant Be in The English Hymnal published in 1906 for the Church of England under the editorship of Percy Dearmer and Ralph Vaughan Williams. Parethetically, the whole Verrall-Vaughan Williams axis figures in her recent talk A Most Sunshiny Day that she performs with actor-singer Pip Barnes.

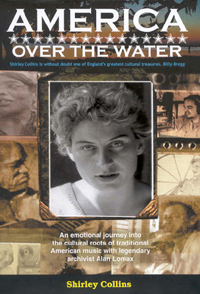

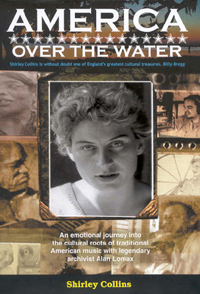

Although she lost her singing voice, she bounced back with a series of talks that range over her work with Alan Lomax (also the subject of her autobiographical account of their 1959 music-collecting trip America Over The Water (2004)), accounts of Southern English Gypsies and, as ever with Pip Barnes, supporting Martyn Wyndham-Read in his account, Down The Lawson Trail – his portrait in words and song of the Australian writer and bush poet Henry Lawson (1867-1922).

For more information go to www.shirleycollins.co.uk

Ken Hunt is the author of the biographical essays about Dolly Collins (1933-1995) and Davey Graham (1940-2008) in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Small print

The copyright of all other images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers. Unless otherwise stated, all interview material is original and copyright Ken Hunt.

18. 4. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Folksong, English, Czech, Hungarian or any other, is all human life in a nutshell distilled, confined or liberated through song. The Sussex singer Shirley Collins’ achievement is unmatched in the annals of twentieth-century folk music anywhere. Blessed with a voice a natural as breathing, she succeeded in bottling and freeing the essence of the songs she sang. When Shirley Collins’ Within Sound appeared in 2002, the boxed retrospective treatment was a relatively new development in folk music. It is utterly appropriate that Shirley Collins should have been Britain’s first female folk singer to get the long-box treatment. Joan Baez’s Rare, Live and Classic (1993) got the US honours in the female folkie category. Shirley Collins got it with the now sold-out Within Sound (Fledg’ling NEST 5001, 2002).

[by Ken Hunt, London] Folksong, English, Czech, Hungarian or any other, is all human life in a nutshell distilled, confined or liberated through song. The Sussex singer Shirley Collins’ achievement is unmatched in the annals of twentieth-century folk music anywhere. Blessed with a voice a natural as breathing, she succeeded in bottling and freeing the essence of the songs she sang. When Shirley Collins’ Within Sound appeared in 2002, the boxed retrospective treatment was a relatively new development in folk music. It is utterly appropriate that Shirley Collins should have been Britain’s first female folk singer to get the long-box treatment. Joan Baez’s Rare, Live and Classic (1993) got the US honours in the female folkie category. Shirley Collins got it with the now sold-out Within Sound (Fledg’ling NEST 5001, 2002).

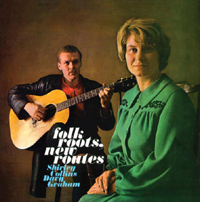

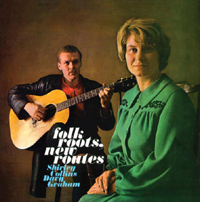

Over the course of her eventful career, Shirley Collins, born in August 1935, had any number of peers but very few equals when it came to England’s folk scene and astonishingly few questionable moments on vinyl. She may have experimented with Irish and American song forms early on (though her inflexions wavered at times on say, Jane, Jane on her and Davey Graham’s co-credited Folk Roots, New Route also anthologised on Argo’s spoken word and music set, Voices), but she never dropped her Southern English accent – as if she could ever get Sussex out of her bloodstream. Within Sound made her achievement and progress patently clear. It need not be said, but let’s say it anyway: Fledg’ling Record’ David Suff and Shirley Collins had a huge body of work to draw upon, and a massive task before them, when cherry-picking the performances that made it to final mastering.

For her, part of the joy inherent in the selection process was rediscovering the worth of and joy in what she had done. “I always knew that The Plains of Waterloo was a great song but it’s a great recording of it too. It’s lovely,” she smiles, “that you can still surprise yourself with your own performance. That’s a bonus.”

On Within Sound, complementing Collins’ official releases on the Argo, Collector, Deram, Folkways, Harvest, HMV, Island, Polydor and Topic labels, is a smattering of judiciously chosen studio and live performances never, if ever, heard by the wider public, since the day she breathed life into them. Chronologically organised, Within Sound takes the listener on an aural journey from Dabbling In The Dew drawn from the various artists’ anthology Folk Song Today (HMV, 1955), and her double LP debut with Sweet England (1959) for Argo in Britain and False True Lovers (1960) for Folkways in the United States – a phenomenal feat at the time – to Lost In A Wood, drawn from Martyn Wyndham-Read’s brainchild, Song Links (Fellside, 2003), a visionary examination setting British and Australian variants of folksongs next to each other.

On Within Sound, complementing Collins’ official releases on the Argo, Collector, Deram, Folkways, Harvest, HMV, Island, Polydor and Topic labels, is a smattering of judiciously chosen studio and live performances never, if ever, heard by the wider public, since the day she breathed life into them. Chronologically organised, Within Sound takes the listener on an aural journey from Dabbling In The Dew drawn from the various artists’ anthology Folk Song Today (HMV, 1955), and her double LP debut with Sweet England (1959) for Argo in Britain and False True Lovers (1960) for Folkways in the United States – a phenomenal feat at the time – to Lost In A Wood, drawn from Martyn Wyndham-Read’s brainchild, Song Links (Fellside, 2003), a visionary examination setting British and Australian variants of folksongs next to each other.

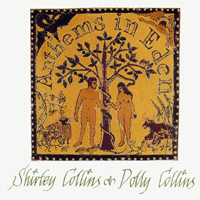

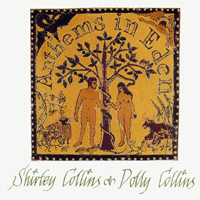

Within Sound contains plenty of the revelations we have come to expect of boxed sets. For example, the run-through of Whitsun Dance – a recording pre-dating her and her arranger-composer sister Dolly Collins’ sessions proper for their 1969 opus magnum Anthems In Eden – is the stuff of dreams. Likewise, the inclusion of her first husband, Austin John Marshall’s song Honour Bright from the never-realised but partially recorded ballad opera The Anonymous Smudge.

As to other comparisons of the creative nature, there is Just As The Tide Was Flowing, as Shirley Collins quips, available “in its three lives” in versions recorded or released in 1959, 1971 and 1979. These were “the straightforward one as we learned from Aunt Grace, then the one with the Albion Country Band and finally a nice arrangement of Dolly’s.” Shirley explains, “That’s an important song because it’s one song that came direct from the family. Nobody else had it [in that version]. If other people sang it they had it in a much rounder form. I still get letters from people saying, ‘You know Just As The Tide Was Flowing; did you know it’s got fourteen more verses?’ My Aunt Grace only knew two verses, so that’s how we sang it.”

Within Sound‘s chronological sequencing makes many things plain, most particularly her development. Beginning near the beginning and treating her first two apprentice pieces, Sweet England and False True Lovers as a single piece of work – they were recorded them back-to-back in one recording session under the watchful eyes of Alan Lomax and Peter Kennedy and then the tracks were divvied up – the listener gets a good feel for the extent of change from one album to the next. Although other work appeared out of sequence, notably the Collins Sisters’ collaboration with the Young Tradition, The Holly Bears The Crown (only finally released in 1995, long after the Young Tradition had broken up in 1969), the official releases between Sweet England and False True Lovers and For As Many As Will (1978) – the final album released under her own name, after which a form of dysphonia stole her singing voice – bear that out.

Between those years, she achieved much of worth. Her second husband, Ashley Hutchings played a prominent part, involving her with the likes of the Morris On bunch, the Etchingham Steam Band, the Albion Dance Band and the Albion Band. Whereas so many folk acts made essentially the same album again and again and again, Shirley Collins showed a steady advance and little or no stylistic repetition once she was recording LPs – and that first release was, remember, in 1959.

She had begun accompanying herself on autoharp or banjo, perhaps augmented with somebody like the physicist John Hasted on guitar. It was all very much in the Fifties’ style of presenting folksong and very much in the stamp of the times. By the time she made The Sweet Primeroses (1967) – ‘primerose’ is a dialect or variant spelling of the commoner ‘primrose’, for the English primrose (Primula vulgaris) – she had five EPs to her name, that collaborative LP with the guitarist Davey Graham (Folk Roots, New Routes, 1964) and a lot of journeyman work to her name and behind her. The Sweet Primeroses was a landmark, not only because it marked the recording debut of her arranger-accompanist-composer sister Dolly on portative pipe organ but because it was one of the albums that stood apart from the trend of the times.

She had begun accompanying herself on autoharp or banjo, perhaps augmented with somebody like the physicist John Hasted on guitar. It was all very much in the Fifties’ style of presenting folksong and very much in the stamp of the times. By the time she made The Sweet Primeroses (1967) – ‘primerose’ is a dialect or variant spelling of the commoner ‘primrose’, for the English primrose (Primula vulgaris) – she had five EPs to her name, that collaborative LP with the guitarist Davey Graham (Folk Roots, New Routes, 1964) and a lot of journeyman work to her name and behind her. The Sweet Primeroses was a landmark, not only because it marked the recording debut of her arranger-accompanist-composer sister Dolly on portative pipe organ but because it was one of the albums that stood apart from the trend of the times.

Whereas the popular face of folk was the smiles and serious faces of television’s Julie Felix, the Spinners and their ilk, Shirley sang Sussex; much like the Watersons sang Yorkshire or Harry Boardman sang Lancashire. A year on and Shirley Collins was making The Power of the True Love Knot (1968), still credited solely to her but with Dolly’s adventuresome arrangements and accompaniments ever more to the fore.

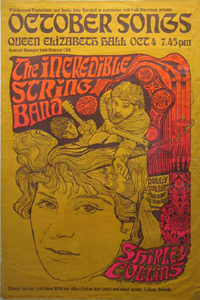

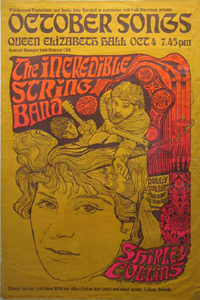

Dolly Collins defined her approach succinctly to me in 1979 for an article in Swing 51: “Let the music be suited to the people [the audience] rather than the people be ‘trained’ to the music”; these were words that her teacher, the composer and doyen of the Workers’ Music Association Alan Bush (1900-1995) might have dictated to her. The Power of the True Love Knot‘s opener, Bonnie Boy uses the cello of Bramwell ‘Bram’ Martin, the cellist on the Beatles’ Eleanor Rigby and She’s Leaving Home but also a mainstay of the ‘Mantovani Sound’, as a colour instrument while Mike Heron and Robin Williamson of the Incredible String Band did their finger-popping stuff on the bonnily romantic, let’s-outdo-Mills & Boon Ritchie Story. (Both tracks are fragrances on Within Sound.) By now, you realised that you were somewhere completely unimaginable at the time of Sweet England. This is less surprising when you know that Austin John Marshall was an early advocate of Jimi Hendrix and had taken Shirley off to see him early on. It was a period of exemplary artistic foment.

Next she asked her audience to take a deep breath and a leap into the unknown with Anthems In Eden. 1969 was the year of Martin Carthy and Dave Swarbrick’s defining Prince Heathen, Ralph McTell’s Spiral Staircase, Judy Collins’ Who Knows Where The Time Goes, Joan Baez’s Any Day Now, Fairport Convention’s Liege and Lief, and the Spinners’ never-better-titled Not Quite Folk. The Sisters’ Early Music, big band album stood out and apart from the throng. Furthermore, it was released in the launch year of EMI’s ‘progressive’ label Harvest. It would sit alongside era-defining work by Pink Floyd, Forest, the Edgar Broughton Band and Deep Purple. Its first side, a complete song-cycle, had first been aired on BBC Radio 1’s My Kind of Folk in August 1968 with the Home Brew and the Dolly Collins Harmonious Band supporting. This, the first of two albums for the ‘underground label’, reached places and audiences denied Radio 1.

Next she asked her audience to take a deep breath and a leap into the unknown with Anthems In Eden. 1969 was the year of Martin Carthy and Dave Swarbrick’s defining Prince Heathen, Ralph McTell’s Spiral Staircase, Judy Collins’ Who Knows Where The Time Goes, Joan Baez’s Any Day Now, Fairport Convention’s Liege and Lief, and the Spinners’ never-better-titled Not Quite Folk. The Sisters’ Early Music, big band album stood out and apart from the throng. Furthermore, it was released in the launch year of EMI’s ‘progressive’ label Harvest. It would sit alongside era-defining work by Pink Floyd, Forest, the Edgar Broughton Band and Deep Purple. Its first side, a complete song-cycle, had first been aired on BBC Radio 1’s My Kind of Folk in August 1968 with the Home Brew and the Dolly Collins Harmonious Band supporting. This, the first of two albums for the ‘underground label’, reached places and audiences denied Radio 1.

Creatively it was a high water mark that she wisely never attempted to reach again. That was not in her nature. Beside the buoyancy and big-budget values of Anthems In Eden, Love, Death & The Lady (1970) seemed a bare affair, reflecting in part its leading ladies’ wretchedness in matters of the heart. Plains of Waterloo captures a rarely paralleled quality of a sombre bleakness and hopelessness. Following Love, Death & The Lady, she returned with No Roses (1971), co-credited to the Albion Country Band, an album with a crew of folk-rock and wayward folk alumni that included Ashley Hutchings on bass, Dave Mattacks on drums, Richard Thompson on guitar, vocalists Maddy Prior (of Steeleye Span) and Royston Wood (late of the Young Tradition), Lal and Mike Waterson. By Adieu To Old England (1975) and For As Many As Will (1978), Shirley and Dolly Collins had gone back to acoustically rooted sensibilities. If the listener picks three (or five) of these albums sequentially starting anywhere in the chronological order, the degree of stylistic difference is astounding. The one constant is her voice. It rarely veered from its Sussex roots.

Creatively it was a high water mark that she wisely never attempted to reach again. That was not in her nature. Beside the buoyancy and big-budget values of Anthems In Eden, Love, Death & The Lady (1970) seemed a bare affair, reflecting in part its leading ladies’ wretchedness in matters of the heart. Plains of Waterloo captures a rarely paralleled quality of a sombre bleakness and hopelessness. Following Love, Death & The Lady, she returned with No Roses (1971), co-credited to the Albion Country Band, an album with a crew of folk-rock and wayward folk alumni that included Ashley Hutchings on bass, Dave Mattacks on drums, Richard Thompson on guitar, vocalists Maddy Prior (of Steeleye Span) and Royston Wood (late of the Young Tradition), Lal and Mike Waterson. By Adieu To Old England (1975) and For As Many As Will (1978), Shirley and Dolly Collins had gone back to acoustically rooted sensibilities. If the listener picks three (or five) of these albums sequentially starting anywhere in the chronological order, the degree of stylistic difference is astounding. The one constant is her voice. It rarely veered from its Sussex roots.

For more information go to www.shirleycollins.co.uk

Small print

The copyright of all other images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers. Unless otherwise stated, all interview material is original and copyright Ken Hunt.

11. 4. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Journey’s Edge is a stepping-stone, a betwixt and between work. It captures Robin Williamson poised in midair or mid-dream skipping from the fading psychedelic sepia of The Incredible String Band and yet to land sure-footedly on the other shore. Though nobody knew that on Journey’s Edge‘s unveiling in 1977. That only became apparent with the Merry Band of American Stonehenge later that year and A Glint At The Kindling in 1978. Journey’s Edge was Williamson’s début solo release after the splintering of the ISB in late 1974. The ISB’s final flurry of creativity – many would have substituted ‘death throes’ – as evidenced by No Ruinous Feud (1973) and Hard Rope And Silken Twine (1974) and the half-remarkable, rarely remembered swansong films Rehearsal and No Turning Back (both 1974), had increasingly bled them of their heyday’s constituency. The thrill had gone. To be frank, Journey’s Edge represented something between foreboding and tenterhooks anticipation. Williamson rose to the challenge, as perhaps only he knew how far to go. Journey’s Edge is relocation music par excellence.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Journey’s Edge is a stepping-stone, a betwixt and between work. It captures Robin Williamson poised in midair or mid-dream skipping from the fading psychedelic sepia of The Incredible String Band and yet to land sure-footedly on the other shore. Though nobody knew that on Journey’s Edge‘s unveiling in 1977. That only became apparent with the Merry Band of American Stonehenge later that year and A Glint At The Kindling in 1978. Journey’s Edge was Williamson’s début solo release after the splintering of the ISB in late 1974. The ISB’s final flurry of creativity – many would have substituted ‘death throes’ – as evidenced by No Ruinous Feud (1973) and Hard Rope And Silken Twine (1974) and the half-remarkable, rarely remembered swansong films Rehearsal and No Turning Back (both 1974), had increasingly bled them of their heyday’s constituency. The thrill had gone. To be frank, Journey’s Edge represented something between foreboding and tenterhooks anticipation. Williamson rose to the challenge, as perhaps only he knew how far to go. Journey’s Edge is relocation music par excellence.

Journey’s Edge‘s tales of journeying and arrival recall his responses to moving from Scotland to the United States at the turn of the year, 1974 into 1975, and his lingering looks back to Europe. Plus the album is very much in the stamp of its time and place of origin with its jazz-funk into Bee Gees’ disco – quite unlike the sound of his first West Coast agglomeration or fling, the Far Cry Ceilidh Band. At a musicians’ party he ran into one of the mainstays of the Merry Band, Sylvia Woods – the deliverer of Journey’s Edge‘s opening flourish and statement of intent on Border Tango. She recalled in an interview in Swing 51 that their meeting happened in December 1975. Woods, under the influence of Alan Stivell had begun playing harp and had gone so far to travel to Waltons in Dublin to buy a harp and harp tutors. She crammed them, Stivell and Derek Bell’s harp playing with the Chieftains into her cranium. She also admitted that before meeting him at the party she had heard neither of Robin Williamson nor the Incredible String Band. But she was working at McCabe’s Guitar Shop on Pico Boulevard in Santa Monica, which doubled as one of the Los Angeles area’s famous folk clubs. It became one of the Merry Band’s regular gigs.

In January 1975 she and Williamson started welding something together, sucking two musicians in her circle, the banjoist Kevin Carr and fiddler Bill Jackson, into their orbit. They were soon replaced by, as it were, the band’s two other, core musicians, Christopher Caswell and Jerry McMillan. The benchmark Merry Band, as they became known, gave their début concert on the 4th of July 1976, thus turning a humdrum date into a memorable one, one that should forever be remembered. Regrettably, Williamson cannot remember where it was. That quartet remains a benchmark of excellence and in Williamson’s memory “a happy band”. They would play their final concert at McCabe’s in December 1979. Although they never told their audience it was their final concert, it went out over national public radio and was subsequently released as an album. “We changed a bit through all the albums,” Sylvia told me in 1980, “but we were the Merry Band with a couple of extra people for Journey’s Edge.”

Williamson’s relocation to Los Angeles led to a burst of creative activity of varying kinds. Much of it was, however, hard to obtain outside continental North America in that great pre-internet age when learning about what he was doing meant reading counter-culture music press and discovering small-circulation literary and music magazines – mine, Swing 51 (1979-1989), being but one. Parallel with sketching, developing and head-arranging the material on Journey’s Edge, he wrote two music tutors for the fiddle and penny whistle, had extracted material from his “surreal autobiography” or “lyric montage” Mirrorman’s Sequence published in the 1977 West Coast anthology Outlaw Visions – it also included the work of writer-composer Paul Bowles and the painter-illustrator Neon Park of Frank Zappa, David Bowie and Little Feat cover art repute – and that year’s co-written thriller called The Glory Trap published under the composite pen name Sherman Williamson.

Fictions, collusions and inventions of varying sorts were Williamson’s forte, he would be the first – or, as Mirrorman, last – to agree. The ISB had revelled in their psychedelic prayer, post-Gilbert and Sullivan silliness and ‘premature world music’ guises. Along the way, at their peak they were shifting enough units and generating enough influence to give Jimi Hendrix and The Supremes a run for their money. But Journey’s Edge is Williamson reaching out to something new, more homespun and – dare one invoke the O-word? – more organic and reaching for things older and more philosophical. Mythic Times captures Williamson claiming again his ancestors of choice and Red Eye Blues his personal Newfoundland while The Maharajah of Mogador is him reclaiming an ancestor for whom he had no choice in the matter, as the said Maharajah came from his wind-up gramophone boyhood. Journey’s Edge is no Childhood’s End. It is no Journey’s End either. It looks to the future. It looks to the past. It is Williamson captured in mid-flight and in trailing-cloud, as they say in Hindlish, air-dash.

December 2006

This is a hitherto unpublished, longer version of some notes written for a reissue that stalled. An expanded edition of Journey’s Edge is available as Fledg’ling FLED 3071 (2008).

More information at www.thebeesknees.com

21. 3. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] East German rock music, nowadays known as Ost-Rock (Ost means east), has never had a champion outside the old East. Sure, Julian Cope got wiggy and witty with Krautrock in all its Can, Kraftwerk and Ohr-ishness. But aside from, say, coverage in the Hamburg-based magazine Sounds in the 1980s and Tamara Danz (1952-1996) – and Silly’s lead singer’s fleeting appearance in the last edition of Donald Clarke’s Penguin Encyclopedia of Popular Music – Ost-Rock got short shrift outside its place of origin, the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Götz Hintze’s Rocklexikon der DDR (2000) and Alexander Osang’s Tamara Danz (1997) biography have redressed the balance somewhat. But Hintze and Osang wrote accounts in German. Probably, no English-language champion will take up Ost-Rock‘s colours now.

[by Ken Hunt, London] East German rock music, nowadays known as Ost-Rock (Ost means east), has never had a champion outside the old East. Sure, Julian Cope got wiggy and witty with Krautrock in all its Can, Kraftwerk and Ohr-ishness. But aside from, say, coverage in the Hamburg-based magazine Sounds in the 1980s and Tamara Danz (1952-1996) – and Silly’s lead singer’s fleeting appearance in the last edition of Donald Clarke’s Penguin Encyclopedia of Popular Music – Ost-Rock got short shrift outside its place of origin, the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Götz Hintze’s Rocklexikon der DDR (2000) and Alexander Osang’s Tamara Danz (1997) biography have redressed the balance somewhat. But Hintze and Osang wrote accounts in German. Probably, no English-language champion will take up Ost-Rock‘s colours now.

Silly were part of a forward-thinking movement, as this 8-CD set shows. The choice of name was a gesture of defiance. German, like every language in my experience, has a plethora of variables orbiting every society’s central and intrinsic idea of stupidity. However, the English word silly captures a special nuance of meaning that kindred German words such as doof, bescheuert or bekloppt do not. Plus, back when, it had the sexiness of an import word in a forbidden language. Russian was the GDR’s second language.

Die 7 Original-Alben – you don’t need a translation – has Silly’s seven Amiga – the only game in town – albums at its heart. You get Tanz Keiner Boogie? (Can’t anyone boogie? or Can’t anyone do the boogie?, 1981), Mont Klamott (the colloquial name of a pimple of a hill, the Grosse Bunkerberg in the Volkspark Friedrichshain in the Berlin district of Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, 1983), Liebeswalzer (Waltz of Love, 1985), Bataillon D’Amour (Love Crowd, 1986), Februar (February, 1989), Hurensöhne (Sons of Whores, 1993) and Paradies (Paradise, 1996) with a judicious scattering of bonus tracks. The set is rounded off with a documentary CD with their vocalist Danz talking about the band.

Somebody obviously tried to make and market Danz as the GDR’s version of Tina Turner with a side-order of Elkie Brooks. Sure, on the surface Tamara had big hair (like Kim Wilde), wore leopard-skin-print pants (like Kim Wilde), and was the whip-crack-away mistress of sublime naughtiness and raunchy sophistication (quite unlike Doris Day). But she was one of the world’s greatest rock vocalists as well. She rocked and Silly rocked, too. Silly’s story is a tale of malcontent music pushing the boundaries, absorbing foreign inspirations (Abendstunden – ‘Evening hours’ – on Mont Klamott album has a certain Vienna vibe, kinda via Ultravox). Silly were at the forefront of the blossoming of something beyond state-tolerated, state-controlled, youth energy-channelling beat music.

One time Scarlett O’ (Seeboldt) – the former female lead singer of Wacholder, then branching out into new musical pastures – and I drove through Berlin. Scarlett is both an education and, as the English idiom goes, a caution. Like we always do, we jawed at length and in detail about how it had been making music in the old GDR. We talked a great deal about Tamara Danz, including her death from cancer. To say that Scarlett O”s respect for Danz was enormous would be an understatement.

Probably, gentle reader, you never heard Silly. I do hope someday you will.

Silly: Die 7 Original-Alben (Sony/BMG Amiga 82876823232, 2006)

14. 2. 2011 |

read more...

[by TC Lejla Bin Nur, Ljubljana] Bonjour (Barclay/Universal, 2009) is Rachid Taha’s eighth studio album since he started on his solo path in 1990. During this time he had released at least two Best Ofs, a hefty pile of remixes, extras & vinyl for collectors and a few concert albums and projects, notably the world-wide resounding success 1, 2, 3, Soleils with Khaled and Faudel in 1998. Before all that, way back in 1980’s, he also recorded about two and a half albums with his band Carte de Sejour. To sum up, he’s come a long way and produced an opulent harvest of quality music that dexterously evades genre labels; in his melting pot he brews rock welded to electro, wrought with music of the world from just about everywhere, obviously and particularly North Africa – all together often encrusted with pop glitter and sometimes even permeated with its essence. After his masterpiece Made in Medina (2000), the coarser Tekitoi (2004) and both his own rootsy compositions on the cover album Diwan 2 (2006) it seemed that this roseate sugar encrustation more or less has fallen off for good in the ripe maturity epoch of master Taha. However, last autumn, a little before All Saints, he struck again with new, screamingly roseate album Bonjour, its soundscape jingling with a wide variety of cheap sweetmeats.

[by TC Lejla Bin Nur, Ljubljana] Bonjour (Barclay/Universal, 2009) is Rachid Taha’s eighth studio album since he started on his solo path in 1990. During this time he had released at least two Best Ofs, a hefty pile of remixes, extras & vinyl for collectors and a few concert albums and projects, notably the world-wide resounding success 1, 2, 3, Soleils with Khaled and Faudel in 1998. Before all that, way back in 1980’s, he also recorded about two and a half albums with his band Carte de Sejour. To sum up, he’s come a long way and produced an opulent harvest of quality music that dexterously evades genre labels; in his melting pot he brews rock welded to electro, wrought with music of the world from just about everywhere, obviously and particularly North Africa – all together often encrusted with pop glitter and sometimes even permeated with its essence. After his masterpiece Made in Medina (2000), the coarser Tekitoi (2004) and both his own rootsy compositions on the cover album Diwan 2 (2006) it seemed that this roseate sugar encrustation more or less has fallen off for good in the ripe maturity epoch of master Taha. However, last autumn, a little before All Saints, he struck again with new, screamingly roseate album Bonjour, its soundscape jingling with a wide variety of cheap sweetmeats.

Album Bonjour wasn’t produced by Taha’s long term collaborator Steve Hillage, the producer of most of Taha’s previous band and solo opus. This time, the producers are New Yorker Mark Plati (who has collaborated with, among others, David Bowie, The Cure) and Gaetan Roussell, the leader of the well known French band, Louise Attaque. Roussell also wrote the music and some of the lyrics for the title song Bonjour, composing three more songs in collaboration with Plati and of course with Rachid Taha, the author of the majority of the music and lyrics. Also new is the ample team of various musicians that recorded this album with Rachid Taha at studios in Paris and New York; only mandolute master Hakim Hamadouche remains from former albums and live performances.

Rachid Taha claims that he gathered this fresh team with a purpose, to bring a new wind to his new album, however (in my opinion) that wind blows from the stifling port and stuffy shopping centre of a Megapolis, not from the spacious seascapes and airy deep spaces of the universe. The rhythms are less interesting, a bit monotonous. Here and there they don’t agree and sometimes come to blows. The same goes for a myriad of various sounds and sound crumbs as well as for the Rachid Taha’s proverbial marriage between Euro-American and North African popular genres; as far as we can even still talk about the latter. Rachid’s vocals are rather straight and one-sided, less multiple, more or less not taken advantage of enough in all its expressive potentials (such as onomatopoetic sounds), probably because the producers don’t know him well enough to know exactly what to do with his voice. And yet Bonjour is still, despite the annoying bits and pieces, punctuated with rare outstanding moments, a solid product of contemporary popular music with Taha’s distinctive beyond-genre flavour.

Taha’s selection of 10 short pieces (allegedly radio friendly 3 to 4 minutes) starts with the love-pleonasm Je t’aime mon amour (I love you my love) and continues with the story of the homeless tramp Mokhtar which offers a hand to Ha Baby, a statement of universal love, which bounds into the title-song Bonjour which claps hands with North African rap Taha style, Mine jai (Where are you coming from). This one goes on into the birth of humanity Mabrouk aalik (Congratulations) which spills onto otherwordly Ile liqa (See you soon), followed by It’s an Arabian song, a duet with French singer and Taha’s old pal Bruno Maman, with whom he also wrote the music, while Rachid’s lyrics are short: “Good is better than evil. Never forget.” The penultimate track, Selu (Ask) with its solid drive, is a tribute to all great minds, the phrase “ask angels” (selu el maleika) is also a wordplay with title-song Bonjour or Salam aleikum. At the end the circle comes around and fastens the way it was opened, with the sensuous and sensitive love lure Agi (Come).

10. 2. 2010 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] An Echo of Hooves represented a career milestone for the English folksinger June Tabor. In February 2004 its Hughie Graeme was named ‘Best Traditional Track’ and she received the accolade of ‘Singer of the Year’ in the BBC Radio 2 Awards. That though is transitory, foreign stuff, for her album An Echo of Hooves was a summation of decades spent learning how to work with, and work out the emotions contained in Anglo-Scottish balladry.

An Echo of Hooves was a culmination of decades of running ballads through the filter of her grey cells. “I’ve been singing ballads ever since I discovered traditional music,” she says. “You’ll find ballads, even if it’s just one, on most of the albums. For some reason, and I couldn’t even tell you what it was now, I wondered whether it would be possible to make an album entirely of ballads that would reflect all the different qualities of the ballad. And, yes, it was possible and I did it and there you have it in An Echo of Hooves.”

An Echo of Hooves was a culmination of decades of running ballads through the filter of her grey cells. “I’ve been singing ballads ever since I discovered traditional music,” she says. “You’ll find ballads, even if it’s just one, on most of the albums. For some reason, and I couldn’t even tell you what it was now, I wondered whether it would be possible to make an album entirely of ballads that would reflect all the different qualities of the ballad. And, yes, it was possible and I did it and there you have it in An Echo of Hooves.”

Her initial collision with traditional balladry – it does have an impact – came, like that of many people, through the school library and treasuries like Arthur Quiller-Couch’s The Oxford Book of Ballads (originally published in 1910). “The traditional ones were always at the front of the anthologies under ‘anon’. Of course, then you find ones further on like The Highwayman which is a cracking story but something written by one person [Arthur Noyes]. Whereas with ‘the ballads’ you just don’t know [about authorship]. I certainly came across them through school.” The next step, however quaint it may sound, was discovering that the words on the printed page were sung. In 1968 she went to study what basically became a French literature course at Oxford and got involved in the university folk society. It led to investing in her own set of Francis Child’s English and Scottish Popular Ballads. “I bought those when I was at Oxford. I went into Blackwell’s Music Shop and bought myself the whole set. Although the folksong society – Heritage – had a library, which was kept in a suitcase, and it had a full set of Child and all the volumes of Bronson that had been published at that time. I’ve always had my set of Childs as a reference tool. I discovered that there was an abridged version of Bronson in one volume, which was ferociously expensive over here, but on one of my trips to America I got it at McCabe’s. They may have ordered it in for me, but that’s how I acquired that. Bronson also has more modern variants of some of the ballads that aren’t in Child because, obviously, Child was working in the nineteenth century and Bronson very much in the later part of the twentieth century. That’s very much the librarian in me, see? I have to have these things! It’s when I think, ‘I wonder if.’ and I go to the shelf. I haven’t got as many books as I would like to have of a musical variety.”

Ballads of whatever hue, nationalistic or border-crossing, are full of archetypes and tales of dark deeds and sturdy steeds. Asked what their direct appeal is, she exclaims, “Oh! it’s just the strength of the storylines. It is narrative poetry in its most extreme form, very stark, no extraneous, superfluous details. It’s great deeds and small ones. Sometimes it can be the minutiae or just like a snapshot. That’s one of the great things about the ballads: they do come in different shapes and in sizes from three verses to however many you’d like to name in unexpurgated versions. But it’s getting a story to move so it just sweeps you along or else it’s one ‘frame’ from the story which leads you to use your imagination or to pick up the clues in the song as to what went before and what’s going to happen next.”

Ballads of whatever hue, nationalistic or border-crossing, are full of archetypes and tales of dark deeds and sturdy steeds. Asked what their direct appeal is, she exclaims, “Oh! it’s just the strength of the storylines. It is narrative poetry in its most extreme form, very stark, no extraneous, superfluous details. It’s great deeds and small ones. Sometimes it can be the minutiae or just like a snapshot. That’s one of the great things about the ballads: they do come in different shapes and in sizes from three verses to however many you’d like to name in unexpurgated versions. But it’s getting a story to move so it just sweeps you along or else it’s one ‘frame’ from the story which leads you to use your imagination or to pick up the clues in the song as to what went before and what’s going to happen next.”

Talking more specifically, she says, “An example of that is Bonnie James Campbell where you get this ‘moment’ when the horse comes back without him and the reaction of the women. I see that song so clearly. I had to sing it. It was one of those ones that had ‘Sing me’ written all over it. Just three verses but so much wealth in implied detail. At the other extreme is Sir Patrick Spens – one hell of a story with very simple language, but so graphic. It’s formulaic, the same verses crop up in other songs, but that doesn’t matter. That also adds to the appeal of the ballad, that the ballad-maker could, with effectively a very limited vocabulary and with a limited number of devices, as a poet, come up with things that were so strong and each in their own way so different. Just as the classic playwrights of the seventeenth century used very limited vocabulary, in Racine for example, but at their best came up with amazing poetry and emotional content from very simple building material. That’s what really appeals to me about the ballads. And they’re good stories too; that’s the other thing.”

Of course, societies nowadays groan with good stories of the cliff-hanging variety from high-flown cinema and highbrow biography to potboilers and soap operas. Ballads are different. “It’s not,” she concludes, “‘I went to the shops and I didn’t see that girl that I fancy from over the road, so I went home and cried a bit.’ There’s probably at least three murders that have happened between here and the newsagent’s! The lives and deaths described are very real and very present somehow. It’s the way that the ballad-maker or -makers, whoever they were, plied their craft. You’re straight inside the story, as soon as you’re into verse one. There’s no messing about. You’re in there and you’re swept along by the song and you’re left somewhat bedraggled at the end.”

June Tabor: An Echo of Hooves (Topic Topic TSCD543, 2003)

A version of this article appeared in the Canadian magazine Penguin Eggs in its Summer 2004 issue. Ken Hunt also wrote the booklet notes and did the interviews for her career overview boxed set Always (Topic TSFCD4003, 2005).

2. 11. 2009 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Forty years or so ago, Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger released their most recondite project, the two-volume Paper Stage. It was reconstructions of the first Elizabethan Age’s theatre for the second Elizabethan Age. The original peddlers of these more unauthorised than guerrilla playlets in song left few traces and fewer fingerprints. All that survived was the printed page. Theirs was street theatre, the equivalent of graffiti artist Banksy’s Mona Lisa with a rocket launcher, or that Banksy rat sawing a getaway hole to freedom through the pavement. Without forcing the analogy, the Paper Stage material somehow survived on paper without the accompanying music, just as Banksy’s long-gone, ephemeral spray paintings and stencil art images survive as photographic images in the book Wall And Piece without the walls.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Forty years or so ago, Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger released their most recondite project, the two-volume Paper Stage. It was reconstructions of the first Elizabethan Age’s theatre for the second Elizabethan Age. The original peddlers of these more unauthorised than guerrilla playlets in song left few traces and fewer fingerprints. All that survived was the printed page. Theirs was street theatre, the equivalent of graffiti artist Banksy’s Mona Lisa with a rocket launcher, or that Banksy rat sawing a getaway hole to freedom through the pavement. Without forcing the analogy, the Paper Stage material somehow survived on paper without the accompanying music, just as Banksy’s long-gone, ephemeral spray paintings and stencil art images survive as photographic images in the book Wall And Piece without the walls.

The year The Paper Stage came together – 1968 – was a year of great flux. It seemed as if it might turn into a watershed year, another 1848 in revolutionary terms. The Vietcong were on the offensive, in the USA Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy were gunned down, Paris, if not France, had its événements and Alexander Dubcek’s Prague Spring was chain-sawed in the bud by Warsaw Pact troops. As frequently happens under repressive regimes, a blossoming of literature and folk poetry occurs. The eight broadside ballads that are The Paper Stage‘s raw material were circulating in a similarly politically charged climate. They were by-products of xenophobia, fear of religious extremists and religious intolerance. Gerontus, The Jew Of Venice reflects that, while A Warning Piece To England Against Pride And Wickedness says it all in the title. “Anything was grist to the mill for the broadside,” laughs Peggy Seeger. “Somebody said, a cat only needs to peep round the corner and some broadsheet seller is selling it by the yard.”

The street performers that delivered these pieces then ducked and dived to sidestep censorship that coloured, conditioned and encrypted Elizabethan and Jacobean plays. Theatre was trickle-down television and film combined. Or like modern-day Trotters and Arthur Dalys they flogged their potted, pirated Taming Of The Shrew or King Lear And His Three Daughters wares to make their daily bread.

The Paper Stage is abridged theatre with a turn of speed, ready to leg it when the lookouts spot the Tudor regime’s killjoys bee-lining towards the gathering. That idea planted a seed. MacColl, Seeger and the Critics Group’s John Faulkner, Sandra Kerr and Dick Snell contemporised their instrumentation deliberately evoking the getaway spirit with portable instruments. They play modern-day ‘folk instruments’ – guitar, tin whistle, concertina and dulcimer – with which light-heeled agit-prop actors or street musicians could run. Implicitly it revisited the ‘appropriate accompaniment’ debate that had occurred during the 1960s. “And tune themselves, quickly,” she adds.

The Paper Stage is the missing link in MacColl and Seeger’s chain of work. It bridges the Bard of Beckenham’s early agit-prop theatre and dramatist past, his love of theatrical history and street-corner minstrelsy. “Ewan loved the Shakespeare plays,” Seeger recalls, “and certain of them he was fascinated by. Titus Andronicus, which is very cruel, for example. He was excited by the theatricality of ballads and the musicality of the speech of Shakespeare. These versions were very singable. That was the thing about them. Very singable. When you look at some of the flowery language that was going on in Elizabethan songs, these stories were almost built like the classic ballads.”

How come The Paper Stage is barely known beyond its title? In Ben Harker’s biography, Class Act – The Cultural And Political Life Of Ewan MacColl (2007) it gets a total of 37 words while MacColl’s own highly selective autobiography Journeyman (1990) makes no mention of the project. There are several possibilities. Many people had developed MacColl and Seeger project fatigue, just as they had the folk cadres’ reviews. There was an awful lot of MacColl and Seeger and it cost an awful lot. Once upon a time, Chorus From The Gallows (1960) about criminals and criminality had lasted one record; at another extreme The Long Harvest ran to ten volumes.

To put it into some sort of financial context, that represented a considerable investment and a great deal of budgeting making a 10-LP set the stuff of public library acquisition. Last, they had to overcome the growing if not prevailing perception that their scholarly inclined, themed work was overly earnest. This reissue provides the first real opportunity to reappraise this project’s importance – or appreciate it for the first time. Do so.

With thanks to Sofi Mogensen at fRoots.

The Paper Stage (CAMSCO 702d, 2008)

Disc 1:

1 The Taming of a Shrew

2 King Lear & His Three Daughters

3 Arden of Faversham

4 The Frolicksome Duke, or The Tinker’s Good Fortune

Disc 2:

5 Titus Andronicus’ Complaint

6 Gerontus, The Jew of Venice

7 The Spanish Tragedy

8 Warning Piece to England

www.pegseeger.com

29. 7. 2009 |

read more...

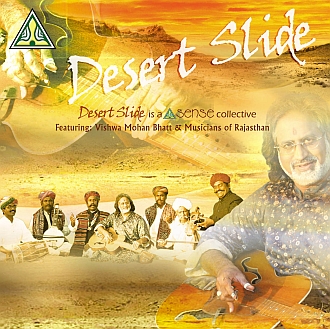

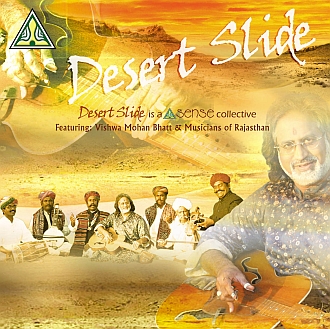

[by Ken Hunt, London] Even by repute, people who have never been to Rajasthan and only ever saw photographs or artwork, view Rajasthan popularly as a region saturated with colour. In its Great Thar Desert, soil, sand and salt lakes offer a palette of yellows, browns and reds. In its deciduous woodlands dhok and dhak – the tree known as the ‘flame of the forest’ – provide the seasonal mosaics of the forest canopy and forest floor and then there is the vibrancy of bougainvillea everywhere whether on the highways or streets. In its street markets full of chillies, mangoes, bananas and spinach, Rajasthan offers an abundance of saturated colours – and watery contrasts. Then factor in whether through raga or folk dance or mela (festival) how musically Rajasthan is affected by what is all around when musicians play.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Even by repute, people who have never been to Rajasthan and only ever saw photographs or artwork, view Rajasthan popularly as a region saturated with colour. In its Great Thar Desert, soil, sand and salt lakes offer a palette of yellows, browns and reds. In its deciduous woodlands dhok and dhak – the tree known as the ‘flame of the forest’ – provide the seasonal mosaics of the forest canopy and forest floor and then there is the vibrancy of bougainvillea everywhere whether on the highways or streets. In its street markets full of chillies, mangoes, bananas and spinach, Rajasthan offers an abundance of saturated colours – and watery contrasts. Then factor in whether through raga or folk dance or mela (festival) how musically Rajasthan is affected by what is all around when musicians play.

An ornithological metaphor springs to mind when it comes to Rajasthan’s traditional music. Jaipur has been home for demoiselle cranes for time out of mind. Huge numbers hug the thermals over the Pink City (Jaipur), landing to strut their courtship and territorial stuff – a source of inspiration for Rajasthani dance. Yet Keoladeo, long the place where Siberian cranes overwintered, has seen the birds’ numbers decrease to next to nothing. What is increasingly happening in Rajasthan – without getting judgemental about the musicians, performers and dancers – is tradition is disappearing in the tourist heat haze. There is a buzz that folk culture is getting as defanged as the palaces’ dancing cobras.

The Desert Slide project bucks any such prevailing trends. A dynamic microcosm, it cross-fertilises two parallel yet different Rajasthani traditions. One is the world of Hindustani classicism that Mohan Vishwa Bhatt playing the Vishwa Mohan vina represents. The other brings together Rajasthan’s two main indigenous and hereditary clans of semi-professional or full-time professional music-makers, namely the Langas and Manganiars (or Manganihars). That commingling of traditions is interesting because it brings together hereditary Hindu and Muslim musicians to common purpose. As a concert and recording collaboration, Desert Slide represents something boldly different in Rajasthani music.

The opening song Helo mharo suno on Desert Slide reinforces the conjoining of traditions. It is a praise song for Baba Ramdev, who was soon revered both as a Hindu deity and an Islamic pir (saint) in Rajasthan. In many ways what is more interesting still than Baba Ramdev crossing that religious divide is him spanning the gulf of caste.

Desert Slide is designed to grab your attention and is the very personification of how musicians embrace vocal and instrumental folk and art music traditions – that business of music connecting rather than dividing.

Let’s dig deeper.

The opening devotional song Helo mharo suno (track 1) is kin to the bhajan form of Hindu hymnody. It is in praise of one of Rajasthan’s most revered Hindu deities and Islamic pirs (saints) of medieval times. Said to have lived from 1469 to 1575 in the Christian Era, Baba Ramdev is linked with the Pokaran district, some 110 km east of Jelsalmer in western Rajasthan and is often depicted on horseback. His worship crosses the Hindu-Muslim divide as well as crossing the caste line since his followers include caste Hindus and the casteless (Dalits or Untouchables) in modern-day Rajasthan and Gujarat – and even further afield into Madhya Pradesh and Sind on the Pakistani side of the border. Several Rajasthani melas (fairs or festivals) celebrate his memory. Helo mharo suno is rooted in râg Bageshri with a sprinkle of râg Shahana and appears in an 8-beat tâl (rhythm cycle). Its title can be rendered along the lines of ‘Hear me calling you’ or ‘Hear my entreaty’. The style of singing is designed to attract attention. And it works remarkably well.

Avalu thari aave, badilo ghar aave (track 2) is a song of separation, a woman’s plea to her beloved (badilo), asking him to come home (ghar). Vishwa Mohan Bhatt plays a theme, a rhythmic melodic hook of his own composition early in the piece to convey a sense of journeying, but the wit of his playing lies in slipping between the interstices of ‘ragadom’. The interpretation is based in râg Bhairav with a little trace of Kalingra, another morning râg, again in the same 8-beat tâl, keherwa or kaharwa as Helo mharo suno. The portrait painted uses filigree brushstrokes, impressionistically summoning the two râgs’ slight difference.

Avalu thari aave, badilo ghar aave (track 2) is a song of separation, a woman’s plea to her beloved (badilo), asking him to come home (ghar). Vishwa Mohan Bhatt plays a theme, a rhythmic melodic hook of his own composition early in the piece to convey a sense of journeying, but the wit of his playing lies in slipping between the interstices of ‘ragadom’. The interpretation is based in râg Bhairav with a little trace of Kalingra, another morning râg, again in the same 8-beat tâl, keherwa or kaharwa as Helo mharo suno. The portrait painted uses filigree brushstrokes, impressionistically summoning the two râgs’ slight difference.