Feature

[by Ken Hunt, London] Planning a trip to England, Scotland and/or Wales? Hoping your visit coincides with some musical adventures? The highly recommended Spiral Earth guide is the ideal place to start planning your time and trip.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Planning a trip to England, Scotland and/or Wales? Hoping your visit coincides with some musical adventures? The highly recommended Spiral Earth guide is the ideal place to start planning your time and trip.

In addition to major fixtures such as Cropredy, Whitby Folk Week, Towersey and Glastonbury, expect to uncover the unexpected – such as the Pipe and Tabor Weekend, Morpeth Northumbrian Gathering and the Sunrise Celebration.

The guide details UK folk, roots and alternative festivals by month and geography with a map to click on. The map won’t allow you to click on, say, the Channel Islands for the Sark Folk Festival and the map doesn’t include Northern Ireland but using the January-April, May, June, July, August and September-December options will get you places by another route. You get the festival’s name, the dates and the website.

Plus it has a breaking news section.

www.spiralearth.co.uk/festivals/default.asp

The images of Fairport’s Cropredy Convention 2008 are © Santosh Sidhu/Swing 51 Archives.

20. 2. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The year started brilliantly, thanks to the Carolina Chocolate Drops and Emily Portman. Then nothing much seemed to happen for the longest while – well, a month or so – and then the sluice gates opened and a wonderful year’s musical experiences began pouring out. It did, however, prove a disappointing year for quality new recordings of Indian music.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The year started brilliantly, thanks to the Carolina Chocolate Drops and Emily Portman. Then nothing much seemed to happen for the longest while – well, a month or so – and then the sluice gates opened and a wonderful year’s musical experiences began pouring out. It did, however, prove a disappointing year for quality new recordings of Indian music.

New releases

New releases

Laurie Anderson / Homeland / Nonesuch

Jackson Browne David Lindley / Love Is Strange / Inside Recordings

Carolina Chocolate Drops / Genuine Negro Jig / Nonesuch

Hariprasad Chaurasia / Hariprasad Chaurasia and the Art of Improvisation /Accord Croisés

Andy Cutting / Andy Cutting / Lane Records

Diva Reka / Diva Reka / Giga New

Barb Jungr / The Men I Love / Naim Label

Ida Kelarova, Desiderius Dužda, Tomáš Kačo and the Škampa Quartet / Romská balada / Indies Scope

Kronos Quartet with Alim & Fargana Qasimov and Homayun Sakhi / Music of Central Asia Vol. 8 – Rainbow / Smithsonian Folkways

Emily Portman / The Glamoury / Furrow Records

Alim Qasimov and Fargana Qasimova / Intimate Dialogue / Drever Gaido

Leon Rosselson & Robb Johnson / The Liberty Tree / Trade Root Music

Peter Rowan Bluegrass Band / Legacy / Compass Records

Steve Smith, George Brooks, Prasanna / Raga Bop Trio / Abstract Logic

Rajan Spolia / More Than Words: Snake Music (Chapter IV)/ Hard World

Jody Stecher / Return / own label

Swarbrick / raison d’être / Shirty

Various Artists / Music of Central Asia Vol. 7 – In The Shrine of the Heart – Popular Classics from Bukhara and Beyond / Smithsonian Folkways

Various Artists / Music of Central Asia Vol. 9 – In The Footsteps of Babur – Musical Encounters from The Lands of the Mughals / Smithsonian Folkways

Wenzel / Kamille Und Mohn / Matrosenblau

Historic releases, reissues and anthologies

Historic releases, reissues and anthologies

Miles Davis / The Complete Columbia Album Collection / Columbia/Legacy

Miles Davis / Bitches Brew / Columbia/Legacy

Bonnie Dobson / Vive Le Canadienne / Bear Family

Swamy Haridhos & Party / Classical Bhajans / Country & Eastern

Incredible String Band / The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter / Fledg’ling

Ravi Shankar / Nine Decades Vol 1 – 1967-1968 / East Meets West Music Inc

Ravi Shankar George Harrison / Collaborations / Dark Horse

Various Artists / Magic Clarinet / NoEthno

Various Artists / Rough Guide to Afghanistan / World Music Network

Various Artists / Theme Time Radio Hour – Season 3 / Ace Records

Events of 2010

Events of 2010

Carolina Chocolate Drops / Bush Hall, Shepherds Bush, London / 4 February 2010

Shraddhanjali – Zakir Hussain, Ranjit Barot and Sabir Khan / Queen Elizabeth Hall, London / 30 April 2010

Amira Medunjanin and Merima Ključo / St Ethelburga’s Centre for Reconciliation & Peace, Bishopsgate, London / 27 May 2010

Jackson Browne / Hampton Court Palace, Surrey / 8 June 2010

Tina Kindermann / Am Markt, Tanz&FolkFest Rudolstadt / 3 July 2010

Diva Reka / Am Markt, Tanz&FolkFest Rudolstadt / 3 July 2010

Kala Ramnath and Abhijit Banerjee / Stadttheater, Tanz&FolkFest Rudolstadt / 3 July 2010

Béla Fleck, Zakir Hussain and Edgar Meyer / Barbican, London / 9 July 2010

Little Feat / Cropredy Festival / 13 August 2010

Martin Carthy and Dave Swarbrick / King’s Place, London / 9 September 2010

The Alim Qasimov Ensemble / Barbican Centre, London / 19 September 2010

Christy Moore and Declan Sinnott / Royal Festival Hall, London / 6 November 2010

Iva Bittová and the Škampa Quartet / Howard Assembly Room, Opera North, Leeds, Yorkshire / 24 November 2010

Images: Smile, taken 20 July 2010 (still possibly a Banksy), and Tina Kindermann at TFF Rudolstadt © Ken Hunt/Swing 51 Archives

The copyright of the other images remains with the original copyright holders.

13. 12. 2010 |

read more...

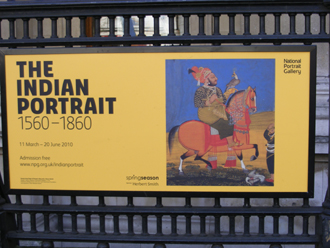

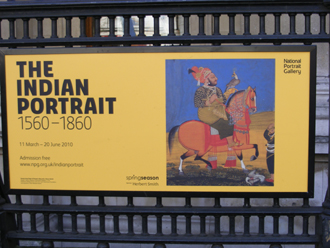

[by Ken Hunt, London] London’s National Portrait Gallery is currently offering two marvellous exhibitions of Indian art. Admission is free and while they may not appear to cast much light of the subcontinent’s musical arts, amid the huqqa smokers, the military figures, nobility and royalty, there are a few correlations between Indian portraiture and aspects of the subcontinent’s music to interest the musically minded.

[by Ken Hunt, London] London’s National Portrait Gallery is currently offering two marvellous exhibitions of Indian art. Admission is free and while they may not appear to cast much light of the subcontinent’s musical arts, amid the huqqa smokers, the military figures, nobility and royalty, there are a few correlations between Indian portraiture and aspects of the subcontinent’s music to interest the musically minded.

The Indian Portrait 1560-1860 draws on works from successive Mughal courts, from an era when patronage – sponsorship in the modern arts vernacular – was keen to log its movements in an era before photography. Amid the portraiture of personages and merchants from Rajasthan, Gwalior and elsewhere in poses with blade and blossom or the courtesans at leisure, three images stand out.

One entitled ‘The vina player Naubat Khan Kalawant’, in fact turns out to be unnamed on the portrait, although the exhibitors or art historians have deduced him probably to be Misri Singh, “a Rajasthani musicians at Akbar’s court who was given the title Naubat Khan” on the basis of him being in charge of the naubatkhani – from the context the gateway above which music was played. He is captured in a stylised setting of plants and small birds rather than any palatial or urban backdrop. His portrait is attributed to Mansur (cryptically “the work of the designer Mansur”) and dated to circa 1590-95. The image is fascinating. He appears to be playing the vina – the two gourds of which are brightly decorated in blue, crimson and gold – but not in the customary seated position as we became accustomed to seeing in the second half of the twentieth century. Instead he looks like a travelling bard and is depicted standing as musicians were later depicted in postcards from the first half of the twentieth century. In picture postcards of nautch (courtesan) entertainers, for example, sarangi players are often depicted standing with the instrument braced against a waist pouch. Interestingly, there appears to be a deliberate attempt to capture Naubat Khan Kalawant’s features as an individual, not as a cipher.

This is in contrast to the Rajasthani portrait called ‘A lady playing a tanpura’ from around 1735 “in ink, gold, opaque and transparent watercolour on paper”. She is unidentified, her features a cipher of the Indian Everywoman. The portrait is all the better for that. Her hair is long and cascades from beneath a bejewelled and pearled turban. She holds her five-stringed tanpura upright (only four tuning pegs are visible). This way she stands for generations of anonymous musicians or nautch entertainers whose features and names are long forgotten. It is on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fletcher Fund. It is a real find. It is available as a postcard.

This is in contrast to the Rajasthani portrait called ‘A lady playing a tanpura’ from around 1735 “in ink, gold, opaque and transparent watercolour on paper”. She is unidentified, her features a cipher of the Indian Everywoman. The portrait is all the better for that. Her hair is long and cascades from beneath a bejewelled and pearled turban. She holds her five-stringed tanpura upright (only four tuning pegs are visible). This way she stands for generations of anonymous musicians or nautch entertainers whose features and names are long forgotten. It is on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fletcher Fund. It is a real find. It is available as a postcard.

Her anonymity is in marked contrast to a portrait of courtesans shown off-duty, loaned from the San Diego Museum of Art, Edwin Binney 3rd Collection. ‘A group of courtesans’, stated to be from Delhi around 1820, depicts six recognisable individuals, perhaps even favourites, with different skin hues, different styles of clothing. The portrait is exquisite and in its detail it casts light on an aspect of culture. Until historical times, most musicians in the subcontinent were faceless. They might play for royalty, the elite and the moneyed but they ate with the servants.

More information at www.npg.org.uk/whatson/exhibitions/the-indian-portrait-1560-1860.php

7. 5. 2010 |

read more...

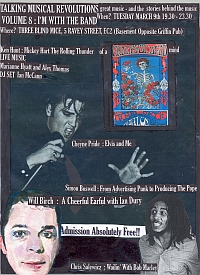

[by Ken Hunt, London] March’s stuff and nonsense comes from Mickey Hart and chums, Joni Mitchell, The Carolina Chocolate Drops, Bob Bralove and Henry Kaiser, Wajahat Khan and the Medici String Quartet, The Six and Seven-Eights String Band, Jo Ann Kelly, Dillard & Clark, Farida Khanum and Sohan Nath ‘Sapera’.

[by Ken Hunt, London] March’s stuff and nonsense comes from Mickey Hart and chums, Joni Mitchell, The Carolina Chocolate Drops, Bob Bralove and Henry Kaiser, Wajahat Khan and the Medici String Quartet, The Six and Seven-Eights String Band, Jo Ann Kelly, Dillard & Clark, Farida Khanum and Sohan Nath ‘Sapera’.

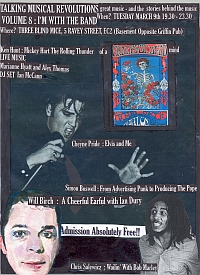

Rolling Thunder/Shoshone Invocation into The Main Ten (Playing In The Band) – Mickey Hart

In 1972 I clapped eyes on Kelley/Mouse’s Rolling Thunder cover artwork in a record rack in the tiny Virgin record store at Notting Hill Gate. It shone out that in some way it was Grateful Dead-related. It turned out that it was the Dead’s absentee drummer Mickey Hart’s solo debut. The opening track sequence draws on and draws in so many threads. Shoshone shaman Rolling Thunder, marimbas from Mike and Nancy Hinton, tabla from Alla Rakha and Zakir Hussain, the whole Calif rock caboodle participating on The Main Ten – John Cipollina and Bob Weir on electric guitars, Stephen Stills on electric bass guitar, Hart on drums, Carmelo Garcia on timbales and the Tower Of Power Horns. That’s why I opted to talk on the subject of Mickey Hart when my fellow writer friend Gavin Martin invited me to talk about anything I wanted at Talking Musical Revolutions 8. From Rolling Thunder (GDCD 4009, 1972)

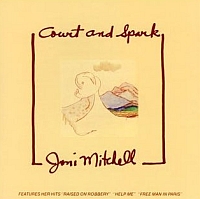

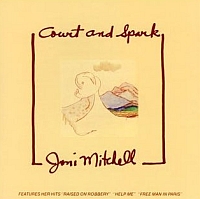

Help Me – Joni Mitchell

A long-running email dialogue with a rather special vocalist planted Help Me in my head and then the song kept rattling around. Potentially, Help Me is ghazal-like in its layered ambiguity. On hearing Help Me at the time of its release, it had seemed very much a woman’s song. Then under the influence of Iqbal Bano and Farida Khanum and a nazm here and a ghazal there, I got to thinking about how gloriously open to re-interpretation Help Me could be, once going beyond the tale of one of Joni Mitchell’s romances that failed to work out. And more importantly, how it might be twisted to reveal new facets and ambiguities with a further turn or two.

A long-running email dialogue with a rather special vocalist planted Help Me in my head and then the song kept rattling around. Potentially, Help Me is ghazal-like in its layered ambiguity. On hearing Help Me at the time of its release, it had seemed very much a woman’s song. Then under the influence of Iqbal Bano and Farida Khanum and a nazm here and a ghazal there, I got to thinking about how gloriously open to re-interpretation Help Me could be, once going beyond the tale of one of Joni Mitchell’s romances that failed to work out. And more importantly, how it might be twisted to reveal new facets and ambiguities with a further turn or two.

The arrangement begins with trademark Mitchell guitar chords (those tunings that always caused a double-take or two) before the band storms in. Her voice on this recording is as smooth as a silken scarf being run through a gold ring. As songs go, it is both as sheer as silk and barbed. As Help Me exits in one channel, in comes Free Man In Paris (another fine song) in the other. One day Joni Mitchell’s Asylum-era is going to get the treatment and sound it deserves. (What is it with the CD’s flat, gated (?) drum sound?) From one of her greatest works Court & Spark (Asylum 7559-60593-2, 1974)

Snowden’s Jig (Genuine Negro Jig) – Carolina Chocolate Drops

It’s always gratifying for the year to start with a humdinger of a concert that really sets the bar high. The Carolina Chocolate Drops did that with their Bush Hall, Shepherds Bush, London at the beginning of February 2010. I was born with two-left feet but when I hear something like Snowden’s Jig I really do wish for some sort of painless transplant that would enable me to do the soft-shoe shuffle. From Genuine Negro Jig (Nonesuch 7559-79839-8, 2010)

Red Queen – Bob Bralove and Henry Kaiser

During his tenure with the Grateful Dead until they folded their hand following Jerry Garcia’s death in 1995, keyboardist-composer Bob Bralove’s role gradually evolved. He and guitarist Henry Kaiser have taken as their starting points on this album an assortment of improvisations that Bralove fashioned in Grateful Dead concerts.

Explaining the project for this here website, Bralove lifts the latch to say, “Ultraviolet Licorice was a recording that was inspired by the back-up material I did for the drums and space parts of GD shows. By the end of the GD I was playing tracks and playing live as segues between drums and space. I recorded all of those performances isolated from the band. I could record just what I was playing to inspire the band to improvise. Henry and I looked at that material which was recorded during the last six years of GD shows and said, ‘Why don’t we use this to inspire us?’ So we went into Fantasy Studios in Berkeley, CA in July of 2008, dropped all of those recordings onto the multi-track and recorded live to them. On that session I played acoustic piano (Steinway Concert Grand) and Henry played electric and acoustic guitars. It was a one day session and a wonderful time.”

Red Queen differs from much of the material on Ultraviolet Licorice. It could almost be a throw-back to Paul Kantner’s Blows Against The Empire. At 2:28, it is the shortest piece on the album and therefore closer in length to Bralove’s Quicksilver Rain, Wind Before The Storm, Urban Twilight and the Bralove/Tom Constanten composition Cowboy Sunset on Bralove’s solo piano album, the delightful Stories in Black and White (BLove 1001, 2007).

Today, the Red Queen conjured in my mind is the Red Queen of Through The Looking-Glass. Tomorrow, she may be a character in a card game. The day after that, who knows? From Ultraviolet Licorice (BLove no number, 2009)

For more information about its participants go to http://bobbralove.com/music.html and http://www.henrykaiser.net/

Raag Desh – Quintet for Sarod and String Quartet – Wajahat Khan and the Medici String Quartet

Desh, also known as Des, is a late evening raga. It is very popular, it is much performed and, personally speaking, it is one of my favourites for the vistas it opens up. The sarodist Wajahat Khan, one of maestro Imrat Khan’s sons, places Desh (it means ‘country’ twinned with ‘homeland’) in a very different landscape to the ones that most interpreters have placed it in. The reason for that is simple: Paul Robertson (violin), Stephen Morris (violin), Ivo-Jan van der Werff (viola) and Anthony Lewis (cello). Collectively, the Medici Quartet. There is such sensitivity apparent here. Khan breaks the performance into four movements: Prayers of Love, Monsoon Memories, Romantic Journey and Celebration. The effect is pastoral and elevates the suite to amongst the highest achievements in East-West classical collaboration. From Wajahat Khan and the Medici String Quartet (Koch 3-6996-2, 2000)

Clarinet Marmalade – The Six and Seven-Eights String Band

The Carolina Chocolate Drops’s gig jolted me into revisiting my past. I thank them for that. The Six and Seven-Eights String Band of New Orleans, though from a parallel tradition to the one the Drops are exploring so ably, could be their godfathers. They are probably more or less forgotten now. More’s the pity. Apparently string band jazz was popular around 1910-1925 in New Orleans but little of it was ever recorded. The Six and Seven-Eights date from that era. They were long gone when that marvellous mandolin maestro David Grisman alerted me to the existence of their solitary Folkways album. Like Dave Apollon, they became part of my back-education.

There is a total joie de vivre – surely the right expression for a New Orleans-based band of such character – to their music. Credits: William Kleppinger (mandolin), Frank ‘Red’ Mackie (string bass), Bernie Shields (steel guitar), Dr. Edmond Souchon (guitar); produced by Frederic Ramsey Jnr and Samuel Barclay Charters. Smithsonian Folkways will do you a copy as part of the archival service. From The Six and Seven-Eights String Band of New Orleans (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings FA 2671, 1956)

The downloadable liner notes are at: http://media.smithsonianfolkways.org/liner_notes/folkways/FW02671.pdf

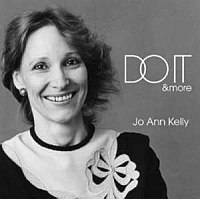

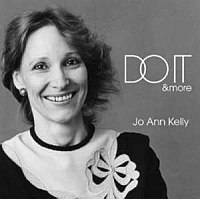

Black Rat Swing – Jo Ann Kelly

It is strange how things can happen. Jo Ann Kelly (1944-1990) was, to my mind, the finest and most natural female blues artist that England ever produced. Her self-titled Epic album was reviewed in one of the first issues of Rolling Stone that I ever saw. She was somebody I would have loved to have interviewed and learned from. We never talked to each other. The irony was that we were frequently tens of yards apart during our lives.

It is strange how things can happen. Jo Ann Kelly (1944-1990) was, to my mind, the finest and most natural female blues artist that England ever produced. Her self-titled Epic album was reviewed in one of the first issues of Rolling Stone that I ever saw. She was somebody I would have loved to have interviewed and learned from. We never talked to each other. The irony was that we were frequently tens of yards apart during our lives.

After she died in October 1990 there was a bash to commemorate her in a pub – the Royal Oak maybe – close to Clapham North tube station in London. The following Sunday I visited my parents in Mitcham on the north Surrey-south London border. As usual, I relayed what I had been up to and mentioned reviewing a musical wake for Folk Roots for a blues singer who had died way too early called Jo Ann Kelly. My mother commented that one of her neighbours five or so doors down had also been called Jo Ann, had been a musician and that she too had died recently. My mother continued that Jo Ann’s partner was called Pete Emery and talked about Jo Ann cycling off with her daughter on the ‘dickey seat’ – a Hunt family joke from my mother’s family’s Singer car’s pannier seat days (sorry about the Saxon genitive mouthful) – of her bicycle, taking her to school. At that point we realised that we were talking about the same person, doors down on the street that I had left two decades before. Never managed to find Pete Emery in afterwards when I knocked. Then when my mother’s illness caused me to move back in, events overtook. It never happened then either.

One of the people I met at Jo Ann’s farewell bash was John Pilgrim, master of the Viper-ish washboard, whip-speed anecdote and quip alike. If I could bottle Pilgro’s recollections and finagle a monopoly on incontinence pads, I would be a very rich man. John plays washboard on Black Rat Swing, a Soho pick-up (honest, it’s a great story) and pre-Pentangle Mike Piggot plays fiddle, the lass sings and Pete bubbles away on electric guitar. It is an epitome of groove. From Do It & more (Hatman 2023, 2008)

www.manhatonrecords.com

The Radio Song – Dillard & Clark

Dillard & Clark – Doug Dillard and Gene Clark – were an act that never achieved their full potential yet what they delivered on their two albums – The Fantastic Expedition of Dillard & Clark (1968) and Through The Morning, Through The Night (1969) – was truly spectacular. The warmth of the harmonies and the strength of the musical support conjure glowing memories. The Radio Song is a performance that I associate with a visit to Collett’s in New Oxford Street at the time of the album’s UK release. Hans Fried – who, with Gill Cook, was one of the lurking presences in that record shop – and I got stuck into good-natured banter about Dillard & Clark and the Flying Burrito Brothers.

The interwoven strands of Dillard & Clark’s voices, the chop-chord and burbling mandolin, steady rhythm guitar and the sly introduction of bowed string bass create the sort of combination you can spend hours – and years – unpicking. From The Fantastic Expedition of Dillard & Clark/Through The Morning, Through The Night (Mobility Fidelity Sound Lab MFCD 791, undated)

Read more about Dillard & Clark at Crawdaddy!‘s online presence:

http://www.crawdaddy.com/index.php/2010/02/02/the-fantastic-expedition-of-dillard-and-clark/?utm_source=NL&utm_medium=email&utm_ca mpaign=100209

Bale Bale – Farida Khanum

Farida Khanum is a Punjabi treasure. That assessment should apply to both sides of the Wagah Border. Regrettably, there is a really unfortunate snootiness on the border’s Indian side towards Pakistan-based artists. This is a piece of Punjabi tradition, praising the gait of Punjabi womankind. Talking the walk, if you prefer. “Bale Bale” – maybe “bole bole” comes closer for Anglophone ears – means, “Say, say”, “Tell, tell”, that sort of thing in the scheme of Punjabi-ness. No doubt there are better recordings of her doing this staple in her repertoire but I really do not care one iota. Don’t be put off by the la-la-la introduction.

There is an ambience and presence to this recording (and her other seven performances on it) that distils so much. This version, the (untranslated) French notes state, comes from the film Pardesi (‘Stranger’ or ‘Foreigner’) after an idea by Martina Catella. It’s a simple song with harmonium, hand-drum and handclap accompaniment. In its simplicity it says so much about the Punjabi character and the perils of division. It’s a very optimistic song. From Pakistan – Musiques du Pendjab, Vol. 2 – “Le Ghazal” (Arion ARN 64301, 1995)

Phagan Ka Lehra – Sohan Nath ‘Sapera’

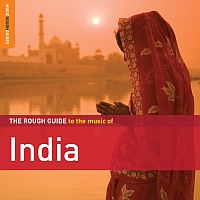

I should apologise for this choice but I’m jolly well not going to. Advance copies of my Rough Guide to India arrived and, like one does, I played it. This piece of Punjabi folk music taps into Ludhiana’s Rajasthani migrant worker influx – think Mexican bracero field workers at whatever picking time in California in particular to get a US parallel – and consequential cultural cross-fertilisation.

I should apologise for this choice but I’m jolly well not going to. Advance copies of my Rough Guide to India arrived and, like one does, I played it. This piece of Punjabi folk music taps into Ludhiana’s Rajasthani migrant worker influx – think Mexican bracero field workers at whatever picking time in California in particular to get a US parallel – and consequential cultural cross-fertilisation.

Shefali Bhushan’s Beat of India from which this snake-charmer music derives is one of the truly great labels promoting India’s folk arts. If there is one more active when it comes to promoting India’s folk music, pray tell. This is music with dirt under its nails, not folkloristic park entertainment or ‘gentrified’ folklore. From The Rough Guide to the music of India (World Music Network RGNET1231CD, 2010)

Context from Aparna Banerji at http://www.tribuneindia.com/2010/20100117/spectrum/book6.htm

11. 3. 2010 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The doom and gloom of recession and depression, inflation and deflation affected people’s lives enormously during 2009. Some say it put dampeners on life. Musically though, on balance it was a year of hope, despite losses.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The doom and gloom of recession and depression, inflation and deflation affected people’s lives enormously during 2009. Some say it put dampeners on life. Musically though, on balance it was a year of hope, despite losses.

New releases

Aruna Sairam / Divine Inspiration / World Village

Damien Barber & Mike Wilson / Under The Influence / Demon Barber Sounds

Szilvia Bognár / Semmicske énekek/Ditties / Gryllus

Kaushiki Chakrabarty / Live at Saptak Festival / Sense World Music

Leonard Cohen / Live in London / Columbia/Sony Music

Gwenan Gibbard / Sidan Glas / Sain

Robb Johnson / The Ghost of Love / Irregular

La Musique D’Issa Sow / Doumale / Home Records

Amira Medunjanin and Merima Ključo / Zumra / Gramofon/ World Village

Cass Meurig and Nial Cain / Deuawd / fflach:tradd

Bea Palya / Egyszálének/Justonevoice / Sony Music (Hungary)

Madeleine Peyroux / Bare Bones / Decca

Martin Simpson / True Stories / Topic

Matt Turner, Peg & Bill Carrothers / The Voices That Are Gone / Illusions

Wenzel / König von Honolulu / Matrosenblau

Wihan Quartet / Beethoven Late String Quartets / Nimbus Alliance

Historic releases, reissues and anthologies

Historic releases, reissues and anthologies

Alistair Anderson / Steel Skies / Topic

Jesse Fuller / Move On Down The Line / Fled’gling

Davy Graham / A Scholar and a Gentleman / Decca

Grateful Dead / Road Trips Vol. 2 – Carousel 2.14.68 / Grateful Dead Productions

Louis Killen / Ballads and Broadsides / Topic

Various artists / 50 Years of Folk Music in Newcastle / Ceilidh Connections

Various artists / Blodeugerdd – Song of the Flowers / Smithsonian Folkways

Various artists / Onder De Groene Linde / Music & Words

Various artists / Theme Time Radio Hour, Season 2 / Ace

Various artists / Three Score & Ten / Topic

Events of 2009

Events of 2009

Aruna Sairam / Darbar International South Asian Music Festival 2009 / Purcell Room, London / 3 April 2009

F. Wasifuddin Dagar / Nehru Centre, London / 8 April 2009

Brass Monkey / The Goose Is Out! DHFC, East Dulwich, London / 15 May 2009

Iva Bittová / Purcell Room, London / 10 June 2009

Leonard Cohen / Mercedes-Benz World, Weybridge, Surrey / 11 July 2009

Richard Thompson / Fairport’s Cropredy Convention, Oxfordshire, England / 14 August 2009

Ridina Ahmedová / Palác Akropolis, Prague / 9 September 2009

Martin Simpson & Big Band / Queen Elizabeth Hall, London / 17 September 2009

Martin Simpson & Big Band / Queen Elizabeth Hall, London / 17 September 2009

June Tabor / Queen Elizabeth Hall, London / 18 September 2009

Vishwa Mohan Bhatt & Salil Mohan Bhatt / Great Hall, Kensington Town Hall, London / 29 November 2009

Bahauddin Dagar / Lecture Room, Victoria & Albert Museum, London / 18 December 2009

Images: Smile (possibly a Banksy) (Ken Hunt), Three Score & Ten (courtesy of Topic Records) and Aruna Sairam and Bahauddin Dagar (Santosh Sidhu).

2. 1. 2010 |

read more...

“Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music is not national at all. It’s become international. It’s become global. That’s what I would also like to reach.” – Alim Qasimov in conversation with Ken Hunt (1999)

“Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music is not national at all. It’s become international. It’s become global. That’s what I would also like to reach.” – Alim Qasimov in conversation with Ken Hunt (1999)

[by Ken Hunt, London] In 1998 Alim Qasimov appeared at Tanz&FolkFest Rudolstadt. He was pretty much an unknown quantity. His recordings were little known outside the Azerbaijani domestic market or France and Switzerland. Qasimov truly was a Francophone find. Queuing outside the Landestheater the German Liederdichter – poet-songwriter – Christof Stählin and I got to talking and he recommended Alim Qasimov’s concert at the town church in a way that brooked no dissent. Once again, I must credit Christof with one of the musical discoveries of my life.

Jeff Buckley (1966-1997) fell for Alim Qasimov’s music too. Their one and only recorded collaboration titled What Will You Say appears on Buckley’s Live A L’Olympia (2001). (It is a tacked on, bonus DAT recording.) In September 2008 Alim Qasimov and his daughter Ferghana Qasimova appeared with the Kronos Quartet at the Barbican in London – and Getme, Getme from that concert graces the Kronos Quartet’s Floodplain (2009). The song had earlier appeared on the album The Legendary Art of Mugham (1997).

Alim Qasimov is one of the world’s most masterful singers. I say his name in the same breath as Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan (1948-1997). On Live at Sin-É (2003) Jeff Buckley says in a rap titled Monologue – Nusrat, He’s My Elvis what the qawwali maestro meant to him. (It is his introduction to Yeh Jo Halka Halka Saroor Hai, a phenomenal feat of memory and brilliantly enunciated delivery for anybody who doesn’t speak Urdu.) Having interviewed both Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and Alim Qasimov and luxuriated in their music at close quarters, it would be churlish to hail one over the other. They rank as two of the finest vocalists of our age. Jeff Buckley wasn’t bad either.

If you want to start on the Alim Qasimov trail, try his Love’s Deep Ocean.

Note: The spelling of Ferghana Qasimova’s name was later standardized as Fargana Qasimova.

What follows is a revised essay, originally written for Alim Qasimov’s debut tour in 2000 that visited Cambridge, London, Coventry and Brighton – organised by Serious, as was the September 2008 engagement.

Alim Qasimov’s home is in Baku – the capital of Azerbaijan, or as many quip, the capital of the Caspian. Some say Baku’s name is a corruption of ‘Mountains of the Wind’ in Persian. Symbolically though this city on the Apsheron peninsula is built from the four elements of the ancients. Its earth is the yellow to beige sandstone out of which so many of its buildings are constructed. Its water is the Caspian Sea. During the winter the salty Hazri bears down cold and chiselling from the north. During springtime the Gilawar wafts in the promise of renewal from the south. But Baku’s fire is both literal and figurative. It is naphtha – the ‘Greek fire’ of the ancients – that lies close to the surface ready to combust and to unite with underground pockets of natural gas. And it is the fieriness of a culture that no number of invaders has ever dampened. Azerbaijan is translated as ‘Place of Fires’ although others say it derives from ‘Protected by Fire’. The philologically hampered can agree on one thing: there is fire in Azerbaijani culture.

Baku has been an economically strategic centre for overland and seaborne trade for over a millennium. It is also one of Transcaucasia’s most important centres of the arts. Famed worldwide for its buildings, Baku’s architectural splendour is like nowhere else on Earth – yet like everywhere where East and West have ever met rolled into one. Only the warp and weft of Azerbaijan’s uttermost cultural and colonial catholicity, cosmopolitan chic, capitalism and Soviet stringency, and, so important, conspicuous oil wealth could have created such an elegant carpet of a culture. Invader, trader and missionary have defined and redefined Azerbaijan’s identity. Pre-Zoroastrian fire-worshippers from the Indian subcontinent, Shi’ite Safavidis, Sunni Ottomans, Hanseatic mariners, French culturalists and Soviet-era commissars of taste have left their masons’ marks all over Baku. Fantastical buildings abound. One building might combine gargoyle and minaret. Another ocean liner sleek and Soviet Constructivism. Another might shuffle Neo-classical, Gothic and French Islamic elements. Even the Electric Railway Station in the old Lenin Avenue – from where trains depart for Tbilisi (the old Tiflis) in Georgia, another major centre of cosmopolitanism – mixes and matches Persian, Egyptian and art nouveau styles, as if at the time of designing the building architect N.G. Bayey, to go mutated Yorkshire for a moment, had a head like an architectural sweet shop.

Baku has been an economically strategic centre for overland and seaborne trade for over a millennium. It is also one of Transcaucasia’s most important centres of the arts. Famed worldwide for its buildings, Baku’s architectural splendour is like nowhere else on Earth – yet like everywhere where East and West have ever met rolled into one. Only the warp and weft of Azerbaijan’s uttermost cultural and colonial catholicity, cosmopolitan chic, capitalism and Soviet stringency, and, so important, conspicuous oil wealth could have created such an elegant carpet of a culture. Invader, trader and missionary have defined and redefined Azerbaijan’s identity. Pre-Zoroastrian fire-worshippers from the Indian subcontinent, Shi’ite Safavidis, Sunni Ottomans, Hanseatic mariners, French culturalists and Soviet-era commissars of taste have left their masons’ marks all over Baku. Fantastical buildings abound. One building might combine gargoyle and minaret. Another ocean liner sleek and Soviet Constructivism. Another might shuffle Neo-classical, Gothic and French Islamic elements. Even the Electric Railway Station in the old Lenin Avenue – from where trains depart for Tbilisi (the old Tiflis) in Georgia, another major centre of cosmopolitanism – mixes and matches Persian, Egyptian and art nouveau styles, as if at the time of designing the building architect N.G. Bayey, to go mutated Yorkshire for a moment, had a head like an architectural sweet shop.

Azerbaijan’s musical heritage is truly the stuff of wonder. Culturally, Azerbaijan – or Azerbaidzhan, as it was sometimes transliterated during its time as a member state in the Soviet Union – is a crossroads culture. It has three enduring influences: pre-Islamic Turkish, Iranian and Islamic. Even though the region has been subjected to external influences for centuries and despite drives to graft Russian and European forms on the region’s Arabic-Persian musical rootstock during the Soviet era, somehow Azerbaijan’s musical traditions have survived with their character intact. In the years immediately after the disintegration of the USSR, as far as all but a very few Europeans were concerned, mugham – the region’s monodic, modal art music analogous to raga – and its ashiq – bardic – traditions were unfamiliar musical concepts. Indeed, it could be joked that for decades Azerbaijan’s musical heritage was virtually the exclusive preserve of French musicologists and it was mainly French labels such as Le Chant du Monde and Ocora that provided the wherewithal to learn about Azerbaijani music.

With them the domino effect began. The world‘s appreciation of Azerbaijan’s musical riches was poised to change. And that was due to Alim Qasimov.

A landmark in the appreciation of non-western classical music

Fittingly Alim Qasimov ranks not only as Azerbaijan’s greatest singer and mugham interpreter but also as one of the world’s greatest vocalists. Without watering down the music in any way, shape or form, however glib it may sound, he has turned the arcane into the accessible. His is a music that rolls in on waves of passion. As anyone who ever saw any of his recitals will attest, Alim’s concerts are nothing less than a before-and-after experience. They rival such decisive debuts in non-western classical music as the arrival of the sitarist Ravi Shankar when he took Hindustani (Northern Indian) raga out of its cultural enclave and introduced it like a software virus to upgrade the West’s cultural programming.

Mugham, like the great modal traditions of Persia and Hindustan, requires melodic and rhythmic dexterity while interpreting lyrics, often of great antiquity by named poets. Azerbaijan has no monopoly on mugham. It is also the art music of Armenia and Uzbekistan and historically the region’s musicians had theoretically only to switch language – Armenian, Azeri or whatever – and keep to the same melodic blueprint. A typical piece opens with a short, introductory mood-setting movement that can be likened to the opening alap movement in a Hindustani raga. The piece then develops a rhythmic pulse, provided by the vocalist’s daf or gaval, a frame drum inside which brass rings and tiny bells hang. Mugham’s foremost instruments for melodic accompaniment are the tar, a long-necked, fretted lute and kamancha or kemanche, a spike fiddle, meaning the instrument is pivoted on its spike, so its strings are turned towards the bow like a flower turns towards the light. Latterly, for studio and concert performances, Alim has augmented this traditional trio instrumentation with additional melody and percussion instruments.

Love’s Deep Ocean (2000) represented a blossoming of Qasimov’s stylistic innovation and again paired him with his daughter Ferghana Qasimova for vocal duets. The measure of the soloist’s skill and art lies in how he – and traditionally it was a he – improvises on the melodic and poetic themes in order to deliver the composition’s emotional charge. The instrumentalists will echo phrases and support the piece’s development. Many lyrics dwell on love in its manifold manifestations, often presented in allegory just as Azerbaijani cuisine wraps ingredients in vine leaves.

Love’s Deep Ocean (2000) represented a blossoming of Qasimov’s stylistic innovation and again paired him with his daughter Ferghana Qasimova for vocal duets. The measure of the soloist’s skill and art lies in how he – and traditionally it was a he – improvises on the melodic and poetic themes in order to deliver the composition’s emotional charge. The instrumentalists will echo phrases and support the piece’s development. Many lyrics dwell on love in its manifold manifestations, often presented in allegory just as Azerbaijani cuisine wraps ingredients in vine leaves.

Alim Qasimov: a pen-portrait

Alim Qasimov was born on 14 August 1957 in the village of Nabur about 100 km from Baku in the Shemakhi region – best known to his countrymen as a home of earthquakes. A mother tongue Azeri speaker – Azeri is a language in the mutually comprehensible Turkish family of languages – he describes his parents as “liberal”. The family took an interest in music. Despite his family’s lowly circumstances and with the blessings of only a basic education, his family encouraged him to pursue his budding interest in music. The proviso was, naturally, that he had to earn a living. Both parents were simple workers. They raised livestock, which their son helped tend, and generally earned money as best they could. Alim learned a great deal about singing and received a great deal of encouragement from his dad, who sang in an amateur way at weddings, parties and gatherings, while to his mother he attributes his sense of rhythm. Dreams of singing mugham do not support families, however.

In the meanwhile, he took a succession of jobs, working variously as a driver, in a laboratory and, almost inevitably, in a refinery. These were frustrating times for him. By 1977 he was married and he felt as if nothing he had turned his hand to had resulted in any sort of success. In 1978 he enrolled in the state music college but impatient with his rate of progress he began studying on his own, absorbing the performance styles of mugham masters on record, attending recitals as purse permitted. His concentrated effort produced success and recognition. Nevertheless, looking back, he admits that while he had the technique and, as he once described it to the German writer Jean Trouillet, the “façade”, to deliver consummate interpretations of mughamat – the proper plural of mugham – he still lacked the maturity to render the soul of the particular mugham. Achieving that required perseverance, patience and the passage of the years. There is no shortcut to maturity in mugham.

Of qawwali, mugham and maestros

Before Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan popularised qawwali with westerners and non-Muslims there had been others, such as the Sabri Brothers, who had alerted a post-war generation to the power of that primarily Pakistani, Sufi devotional form on record. Just as before Alim Qasimov there had been others. (In the case of qawwali and Persian-Tartar (Azeri) music, there had been commercial pressings as far back as the beginning of the twentieth century for local consumption.) The impact of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan on the world of Islamic music as a whole cannot be underestimated and he had a rejuvenating effect on qawwali, as Alim Qasimov has had with mugham, as happened when a visionary introduces innovations grounded in a musical tradition.

During the early 1990s Alim had the opportunity to see Nusrat perform in France. “His concert opened a lot of doors for me,” he told me, “answered a lot of questions. After watching him, I became a lot freer in my own interpretation of mugham music.” Qasimov would contribute to Hommage à Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan (1998), a tribute anthology that did much to spread the word about Qasimov’s greatness in the broader river of Islamic-derived musics. Alim admits that his music does not automatically tap into the Islamic or Koranic, although in a deeper spiritual way it does in its Sufi-like use of allegory, lyrical structure and its kinship with Persian mystical and poetic forms.

During the early 1990s Alim had the opportunity to see Nusrat perform in France. “His concert opened a lot of doors for me,” he told me, “answered a lot of questions. After watching him, I became a lot freer in my own interpretation of mugham music.” Qasimov would contribute to Hommage à Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan (1998), a tribute anthology that did much to spread the word about Qasimov’s greatness in the broader river of Islamic-derived musics. Alim admits that his music does not automatically tap into the Islamic or Koranic, although in a deeper spiritual way it does in its Sufi-like use of allegory, lyrical structure and its kinship with Persian mystical and poetic forms.

Of prizes and praise

It takes neither a cynic nor a sceptic to be chary about music industry awards and prizes and the way statuettes or gongs are given out. Too many are corporate or media circuses, occasions for little more than mutual backslapping, brown-nosing or a chance to get a marketing and monetary edge on the competition. How many awards really count?

On 19 November 1999 in the Krönungssaal – the crowning room of the Holy Roman Empire – in Aachen’s town hall Alim Qasimov was the joint winner of something sounding as if it was somewhere on a sliding scale between officiousness and officialdom called the International Music Council-UNESCO Music Prize. The difference with this one is it is nicknamed the ‘Nobel Prize for Music’. And it is given only to “musicians and musical institutions whose work or activities have contributed to the enrichment and development of music and have served peace, understanding between peoples, international co-operation and other purposes proclaimed by the United Nations Charter and the UNESCO Act.”

With the award of the IMC-UNESCO Music Prize, Alim Qasimov joined a select company of musical paladins. The first recipients of the prize in 1975 were Dmitri Shostakovich, Ravi Shankar and Yehudi Menuhin. In between its recipients had included Leonard Bernstein, Herbert von Karajan, Oliver Messiaen, György Ligeti, Krzysztof Penderecki, Iannis Xenakis, Benny Goodman, Daniel Barenboim, Mercedes Sosa, Cesaria Evora, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and, co-winner with Qasimov in 1999, Emmanuel Nunes. Qasimov’s accolade gave an international fillip to the ‘mugham cause’.

And with it a new age began.

Alim Qasimov Ensemble Azerbaijan: The Legendary Art of Mugham Network 28.296 (1997)

Alim Qasimov Love’s Deep Ocean Network 34.411 (2000)

Jeff Buckley Live A L’Olympia Columbia COL 503204-9 (2001)

Jeff Buckley Live at Sin-É Columbia COL 512257 3 (2003)

Kronos Quartet Floodplain Nonesuch 7559-79828-8 (2009)

Ken Hunt’s German-language article from the 6/99 issue of Folker! – Germany’s finest folk and world music magazine – is available online at http://www.folker.de/9906/quasimov.htm

15. 6. 2009 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Oh, he was a one!

“Jamie, come try me,

“Jamie, come try me,

Jamie, come try me,

If thou would be my love

Jamie, if thou would kiss me love

Wha [who] could deny thee

If thou would be my love, Jamie?”

Wilily the writer is putting his words onto a woman’s tongue, the woman he wishes to get to know better. Or, in plainer talk, seduce. Thus when Eddi Reader flirts entreating the man – the very author of the words pulsating on her lips – to try her, there is a delicious, besotted undercurrent of contrary sensuality in flow. That is Eddie Reader and Robert Burns for you.

On Eddie Reader’s lips – even with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, as on The Songs of Robert Burns blasting away in support – that song, Jamie, Come Try Me, is a song of sensuality, seduction and ambiguity. Ambiguity, because we can only imagine the inevitable ending of this piece of come-hither theatre. Mind you, the way Eddie Reader sings it, her performance makes destiny plain. And that inevitability is plainer still when she sings Jamie, Come Try Me without the orchestral flourishes on one of her live releases. Live: Newcastle, UK 24.05.03, for example.

England and the world have their William Shakespeare. Russia and the world have their Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin. Elsewhere, when it comes to the international stage, few nations have produced a literary giant to compare with Scots poet-sangster Robert Burns (1759-1796). Likely as not, time will see Bob Dylan as similarly internationalist but that is a judgement for posterity not for here and now, for none of us will ever know that with the certainty that we can say that of Burns, Pushkin or Shakespeare in our lifetimes. That is not to say that Burns had an easy ride during his lifetime or his work has had an easy passage since his death. There is a lot of tartan and haggis out there to sidestep.

In August 2002 the Eddie Reader of Perfect and Patience of Angels returned to home to Glasgow and she threw herself into a Robert Burns project involving the likes of double-bassist Ewen Vernal and multi-instrumentalist Phil Cunningham for the January 2003 Celtic Connections festival. The Songs of Robert Burns was originally released in 2003. It re-appeared in an expanded edition in January 2009, timed to coincide with the 250th anniversary of Burns’ birth. In many ways though Eddie Reader’s roots lay in Irvine however, not Glasgow.

Eddie Reader and Ken Hunt talk about Burns

Eddie Reader: In Burns’ day Irvine was a massive port and he met all these merchant sailors there. They taught him about drinking and women and song. When he was living in Irvine, he was trying to become a flax dresser. He ended up living in Irvine for a year and a bit. He wound up getting really ill. Eventually he had to come home because he only had a bag of oats left to last him six months. While he was in Irvine he’d write things like “Dainty Davie” and he met a wonderful sailor called [Captain] Richard Brown. The guy really influenced him. He wrote lots of poems about him.

Eddie Reader: In Burns’ day Irvine was a massive port and he met all these merchant sailors there. They taught him about drinking and women and song. When he was living in Irvine, he was trying to become a flax dresser. He ended up living in Irvine for a year and a bit. He wound up getting really ill. Eventually he had to come home because he only had a bag of oats left to last him six months. While he was in Irvine he’d write things like “Dainty Davie” and he met a wonderful sailor called [Captain] Richard Brown. The guy really influenced him. He wrote lots of poems about him.

You couldn’t help but be affected by the countryside, the sea and the harbour.

Ken Hunt: If I’m writing about something I love visiting the places where things happened. Do you do that at all? Talking about Burns specifically. To feel the vibrations. I know that sounds a bit hippy, but you know what I mean.

I know exactly what you mean! Doesn’t everybody do that? I hope. I absolutely adore the history of something.

I know exactly what you mean! Doesn’t everybody do that? I hope. I absolutely adore the history of something.

I was talking to Natalie MacMaster about this. She’s so sweet when she’s playing and I know when she’s playing it’s her genetics that are playing, not her. I look at her in her modern clothes and it’s like someone else’s fingers, her great-great-grandfather’s fingers, are moving. I said to her what it is to me is when you get a song and it’s almost like finding a bit of gold in a junkshop, the junkshop of human emotions. You find what someone has written 300 years ago is equally as relevant as something written today. When you find it in a book or you go and visit, say, Burns’ house and you know he actually stood on the step there, leant over that bed, poured over that sink or picked up a kid from that floor, it always makes something a little bit more real. Definitely. You can identify on a human level because you do these things now, so you know they must have done them all. It’s great for me the more involved I get in Burns. As I walk into a graveyard, there’s the grave of Jessy Lewars, who he wrote O, Wert Thou In The Cauld Blast for and who nursed him.

I go to Mauchline where Burns was brought up from the age of 16 through to when he left to become a star in Edinburgh at the age of 28. Those ten years in Mauchline he became a star in the town. The good thing about Burns is that most of his poetry is about people. It’s a description of somebody or a story about somebody. All of these people existed. They were real. They wouldn’t be mentioned hardly at all probably if it weren’t for this little guy wrote some poems about them. I get a great sense of affection for Burns and most of all when I’m in his environment. Definitely.

Do you get a sense of serenity from that…

Well, I’m quite a serene person anyway, I think.

…in a sense of heightened serenity?

I’m very excited when I’m finding these things and I’m in that environment. I commune with… Actually, I think I probably feel more removed from the character of Burns when I’m visiting a house, much more than when I’m singing the songs. When I’m singing the songs I feel like he’s singing them with me. Or he’s watching me or dancing with me. Or whatever.

I’m very excited when I’m finding these things and I’m in that environment. I commune with… Actually, I think I probably feel more removed from the character of Burns when I’m visiting a house, much more than when I’m singing the songs. When I’m singing the songs I feel like he’s singing them with me. Or he’s watching me or dancing with me. Or whatever.

I’m much more connected to him and who he was when I’m singing the words.

Is there a sense of being energised?

Energised as well. Definitely energised. I’m never tired when I’m singing Burns’ songs. My voice never tires. There’s no hard work in it at all. Energised, yeah, more so than being in a house that’s been whitewashed three million times. And maybe the mattress isn’t the same! Visiting his old haunts definitely fills me with joy. When I see them for the first time it’s wonderful.

Photographs: Colin Dunsmuir, courtesy of Rough Trade. All rights reserved.

Eddi Reader The Songs of Robert Burns Rough Trade RTRADCDX097, 2009

To follow Eddie Reader’s activities http://www.eddireader.co.uk/ is the topmost of top tips.

12. 3. 2009 |

read more...

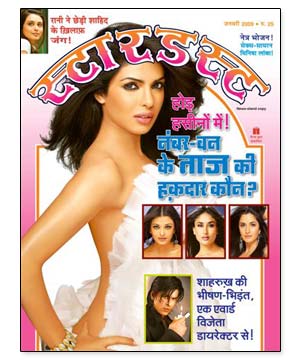

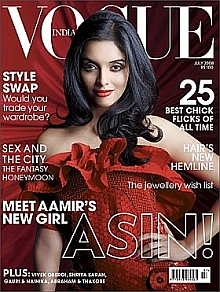

[by Ken Hunt, London] Wherever there is a successful film industry, like the penumbra to the klieg lights, film magazines will mushroom in order to feed people’s apparently insatiable appetite for news – planted or otherwise – and tittle-tattle. In the Anglophone world, from Picture Show (when ‘picture’ was the British Empire equivalent of ‘movie’) to the “Hollywood girls and gags!” of Movie Humor, cinema was well served from the silent era onwards. But India’s was, is and shall ever remain a special case.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Wherever there is a successful film industry, like the penumbra to the klieg lights, film magazines will mushroom in order to feed people’s apparently insatiable appetite for news – planted or otherwise – and tittle-tattle. In the Anglophone world, from Picture Show (when ‘picture’ was the British Empire equivalent of ‘movie’) to the “Hollywood girls and gags!” of Movie Humor, cinema was well served from the silent era onwards. But India’s was, is and shall ever remain a special case.

India has long been home to the world’s biggest film industry. Numerically and in terms of cultural penetration it outstrips Hollywood. Yet it is more than Bollywood. It includes the other major cine-woods – notably Kollywood (the Kolkata-based, Bengali equivalent), Mollywood (the cinema of Kerala in Malayalam), and Tollywood (the Chennai-based Tamil film industry).

Cinema spread like commercial wildfire in the Indian subcontinent from the 1890s, further to the brothers Auguste and Louis Lumiere showing their first reels in Bombay in July 1896. In a country in which illiteracy or near-illiteracy is still the norm in many states so many decades after Partition in 1947, silent film engaged and caught the public imagination with religious dramas, tales of the supernatural and slapstick, visual comedy. They transcended language and literacy skills. They glued the nation together and became a sort of neo-folklore. They re-defined and determined what popular culture meant. Film became the dominant cultural medium, displacing travelling companies and traditional theatre.

The arrival of film song

In 1931 India launched its own talkies. Ardeshir M. Irani’s adaptation of a Parsee drama Alam Ara (‘Light of the world’) narrowly became India’s first talkie. Irani gave the subcontinent its first filmi sangeet (‘film song’) singer in W. M. Khan. Importantly, he used the same device – song and music – that the peripatetic theatre companies had used and were still using. Alam Ara became a hit that travelled too. A hit in India could be a hit too in, for example, Ceylon and Burma. Just as later Bombay film industry movies were hits in other continents in ways that Hollywood could not be. Hollywood came to epitomise Amerika, its values, its cultural myopia and especially its foreign policies. Bollywood films were and remain both neutral and, in the main, escapist. They carry none of the neo-imperialistic baggage of Hollywood.

In 1931 India launched its own talkies. Ardeshir M. Irani’s adaptation of a Parsee drama Alam Ara (‘Light of the world’) narrowly became India’s first talkie. Irani gave the subcontinent its first filmi sangeet (‘film song’) singer in W. M. Khan. Importantly, he used the same device – song and music – that the peripatetic theatre companies had used and were still using. Alam Ara became a hit that travelled too. A hit in India could be a hit too in, for example, Ceylon and Burma. Just as later Bombay film industry movies were hits in other continents in ways that Hollywood could not be. Hollywood came to epitomise Amerika, its values, its cultural myopia and especially its foreign policies. Bollywood films were and remain both neutral and, in the main, escapist. They carry none of the neo-imperialistic baggage of Hollywood.

Song – filmi sangeet – was the magic elixir that cinema-goers gulped down. The unlettered with ‘compensatory’ oral skills left having learnt the catchiest songs on first pass or a close enough take on the song to sing what passed as it to friends and family. Where once silent cinema had used mythic and religious stories to attract audiences, music now was the new universal element. That and spectacle. Increasingly song ‘choreographed’ to lavish dance scenes may have dislocated and suspended the narrative flow but they made borderline hits hanging on a whim and a prayer box-office magic. One great song could launch a film into the financial stratosphere.

Cinema magazines

Cinema magazines

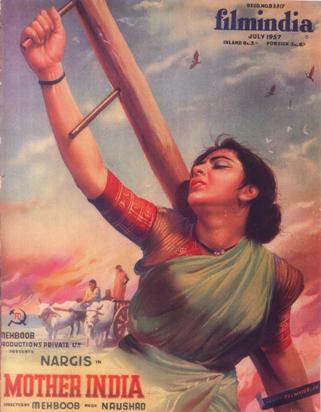

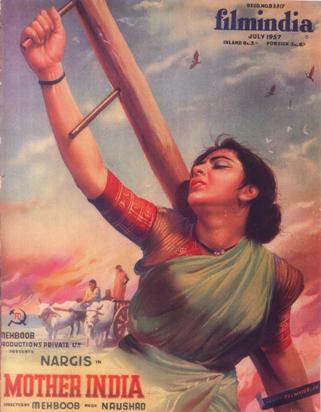

The film industry appreciated the power of words in print. People bought commemorative programmes for the film. These souvenirs had eye-grabbing cover graphics (often of the highest pictorial and printing standards), film credits and plot synopsis. They also had the printed lyrics to songs. These might be in Arabic or Shahmukti script and Devanagari for Urdu and Hindi readers respectively. The Mother India painting on the cover of Film India above is typical of the quality of these souvenir programmes’ artwork and shows why they were so prized.

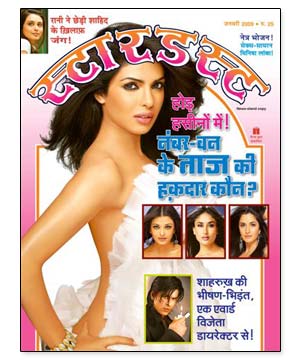

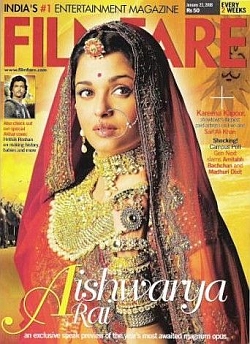

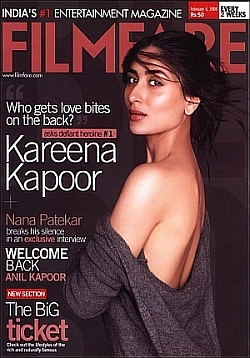

But from early on, the Indian film industry was also well served by film magazines. Bollywood may get the lion’s share of attention at home and abroad but cinema coverage has always extended (if an absolute like ‘always’ can ever be said or permitted) to regional cinema in regional languages. As a sociological phenomenon, India’s film magazines – and its letters pages – are the litmus test of the duality of conservatism and changing cultural and moral values. Yet whether discussing Dev Anand or Amitabh Bachchan, Helen or Aishwarya Rai, Guru Dutt or CyberIndian SFX, the coverage has stayed true to the lakh (100,000) and crore (100 lakh or 10,000,000) principles of success and failure.

As happened in Hollywood and Britain, Indian film magazines swiftly tapped into allure and celebrity, the stock-in-trade of today’s English-language titles like Cine Blitz, Filmfare (or Film Fare), g magazine, Movie and Stardust. With the arrival of the talkies in India, the hunger for titillation through alleged liaisons and rumoured off-screen snogs steadily grew. During the 1930s, publications like The Cinema, Film India (or filmindia) and Filmland dominated the English-speaking readership. Film India, the brainchild of Baburao Patel, was especially influential and Patel’s eviscerating reviews were greeted with grimace and glee in varying measures.

Between the 1950s and 1970s, a slew of new titles arrived. These included Film World, Filmfare, Madhuri, Screen, Stardust and Star and Style. Some survived. Most were gobbled up or went under. Following the Darwinian model though, when one went under other magazines appeared. Cinemaya (maya fittingly means ‘illusion’), launched in 1988, was but one that plugged a gap.

Between the 1950s and 1970s, a slew of new titles arrived. These included Film World, Filmfare, Madhuri, Screen, Stardust and Star and Style. Some survived. Most were gobbled up or went under. Following the Darwinian model though, when one went under other magazines appeared. Cinemaya (maya fittingly means ‘illusion’), launched in 1988, was but one that plugged a gap.

By the 1970s Stardust was arguably the market leader. Still, Filmfare had its prestigious awards that bolstered its reputation. The awards polarised and still polarise opinion – especially when a particular film, actor or song failed to scoop a particular award. Never underestimate controversy.

The Bombay-based Cine Blitz proved a particularly important title. Its launch issue in December 1974 rang bells like a sure-fire attention grabber. Prominent was a piece about flower-child Protima Bedi, later a gifted Orissi classical dancer. It came with photos of her streaking – a gesture of liberation and progressiveness unparalleled in denial-ridden, pseudo-moralistic India – on Bombay’s Juhu Beach. Of such circulation fillips are lakhs made.

Regionally based bilingual titles such as the English-Gujarati Ranjit Bulletin also emerged. They were, to home in on Gujarati, today’s Abhiyaan (roughly something between ‘work’ and ‘mission’) and its forerunners like Cinema Sansar (sansar, as a word, summons a serried bank of meanings including ‘home’ and ‘humanity’) and Moj Majah (‘Enjoyment’). Elsewhere in the subcontinent, print and online publications devoted to cinema have flowered. Malayalam has its Villinakshatram and Chithram and Kannada its Viggy and Chitraloka. Many have bilingual presences. There are many more examples beyond the Bollywood blogster hordes.

Regionally based bilingual titles such as the English-Gujarati Ranjit Bulletin also emerged. They were, to home in on Gujarati, today’s Abhiyaan (roughly something between ‘work’ and ‘mission’) and its forerunners like Cinema Sansar (sansar, as a word, summons a serried bank of meanings including ‘home’ and ‘humanity’) and Moj Majah (‘Enjoyment’). Elsewhere in the subcontinent, print and online publications devoted to cinema have flowered. Malayalam has its Villinakshatram and Chithram and Kannada its Viggy and Chitraloka. Many have bilingual presences. There are many more examples beyond the Bollywood blogster hordes.

The National Film Archive of India

First established in 1964, the National Film Archive of India (NFAI) is an organisation based in Pune with repositories in Bangalore, Kolkata and Thiruvananthapuram. Affiliated to the International Federation of Film Archives, the Pune site houses the ever-expanding national collection of film-related holdings with some 50,000 books and Central Board of Film Certification scripts, censorship records from the 1920s onwards and the main national archive of periodicals from the early 1930s onwards. Month in, month out, the NFAI acquires all the nation’s most important newspapers and periodicals on the subject – an indication of the commensal relationship between India’s press and the subcontinent’s film industry. Come the day its website expands, www.nfaipune.gov.in will become a useful tool internationally worthy of an international cultural phenomenon.

The paradox

The paradox

The major paradox is that, given the scale of music’s contribution to the industry, how little serious attention film music got historically and generally gets nowadays. Although, in the parlance of the time, “Miss Nurjehan” graced the cover of The Cinema as far back as 1931 – albeit, at the risk of blowing the relevance of the citation, as an actress rather than as a playback singer – the only publication that has consistently carried in-depth coverage of the Indian music scene is Screen, Mumbai’s weekly broadsheet-style paper. Through its succession of historian-minded journalists and name columnists such as Mohan Nadkarni reflecting on classical music from A. Narayana Iyer to Bhimsen Joshi and Rajiv Vijayakar doing detailed Q&A pieces about people like the Saawariya and Bhool Bhulaiyaa songstress Shreya Ghoshal, Screen has proved itself the magazine since the 1950s with, arguably, the keenest grasp of music in its Indian film context.

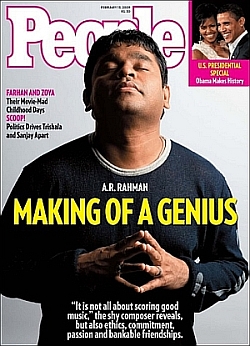

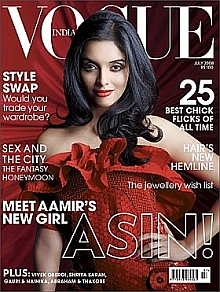

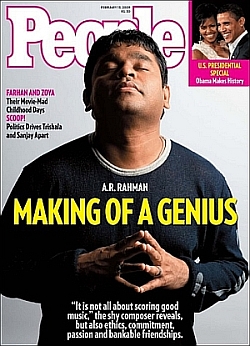

Indian cinema is big business. Just as Filmfare covets an Aishwarya Rai or Kareena Kapoor front cover and interview, mainstream titles like Vogue India or India Today want the sales boost an Aishwarya Rai cover brings. It is interesting that titles like People and Rolling Stone are covering Bollywood’s musical side now. Nowadays a musical phenomenon such as A.R. Rahman merits the full front cover treatment. Of course, Rahman comes trailing clouds of glory such as Bombay Dreams, Lord of the Rings and Slumdog Millionaire. (Tellingly none of them is Bollywood.) It is a far cry from Mojo commissioning me to write an article about Rahman and then retracting the commission after the interview was in the can because he was deemed a month later to be far too obscure to merit a single column inch.

Indian cinema is big business. Just as Filmfare covets an Aishwarya Rai or Kareena Kapoor front cover and interview, mainstream titles like Vogue India or India Today want the sales boost an Aishwarya Rai cover brings. It is interesting that titles like People and Rolling Stone are covering Bollywood’s musical side now. Nowadays a musical phenomenon such as A.R. Rahman merits the full front cover treatment. Of course, Rahman comes trailing clouds of glory such as Bombay Dreams, Lord of the Rings and Slumdog Millionaire. (Tellingly none of them is Bollywood.) It is a far cry from Mojo commissioning me to write an article about Rahman and then retracting the commission after the interview was in the can because he was deemed a month later to be far too obscure to merit a single column inch.

This leads us to that final question: that paradox. Given the importance of filmi sangeet in as the world’s most popular popular music form, where beyond the Lata Mangeshkar biographies are the magazines and books dedicated to India’s film song? Where is the detailed and in-depth coverage of this extraordinary popular music that out-performs rock, rap and reggae?

The good thing is that this feels curiously like being on the brink, like being witness to an exhilarating period. As happened, to give Western examples, when small magazines started running informative and informed, in-depth and passionate articles about rock or folk or punk as a reaction to the mainstream music press still treating those phenomena as mere youth crazes or passing fads. For, after all, when all is said, done and debated where would Indo-Pakistani film be today without filmi sangeet?

Ken Hunt is the author of the chapters on the Indian subcontinent’s music in the second and third editions of The Rough Guide to World Music. He compiled The Rough Guide to Asha Bhosle (World Music Network RGNET 1131 CD, 2003), The Rough Guide to Lata Mangeshkar (RGNET 1132 CD, 2004), The Rough Guide to Mohd. Rafi (RGNET 1133 CD, 2004) and The Rough Guide to Bollywood (RGNET1179CD, 2010).

3. 3. 2009 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Chancing upon the final-cut premiere of Alex Reuben’s film Routes was kismet. Alex Reuben is a DJ and filmmaker – British out of Ukrainian Jewish stock – with shorts like Big Hair (2001) and A Prayer From The Living (2002) to his credit. “I was a DJ so that’s how I started making films,” he tells me in Prague “Through the money I made DJing, that’s how I made films. All of the films are related to DJing in some way. More in the method I make them, though.”

[by Ken Hunt, London] Chancing upon the final-cut premiere of Alex Reuben’s film Routes was kismet. Alex Reuben is a DJ and filmmaker – British out of Ukrainian Jewish stock – with shorts like Big Hair (2001) and A Prayer From The Living (2002) to his credit. “I was a DJ so that’s how I started making films,” he tells me in Prague “Through the money I made DJing, that’s how I made films. All of the films are related to DJing in some way. More in the method I make them, though.”

Routes is the eye-catching offspring of Harry Smith and Les Blank. Picaresque, without spoken commentary, it is a fly-on-the-wall, fly-on-the-windscreen road movie about dance encountered on a journey through the Southern States of America. Reuben’s focus is dance, down-home and urban, dance steeped in tradition or dance stepped in emergent dance forms like clowning, krump and hiphop. It opens with a sequence of barefooting – a hybrid between clogging and a form of barefoot dancing associated with Negro slave ships – performed on a square of wood to fiddle, guitar, banjo and double-bass accompaniment. Only these are white feet dancing and white musicians pounding out dance rhythms at the Shindig on the Green in Ashville, NC. As he drives to New Orleans – the travel footage feeds the narrative, seldom seeming makeweight or ‘make-length’ – he encounters white, black and Native American dancers in settings that include solo dancers, family pair dancing and what looks like sprung ballroom, Cajun and zydeco, clowning, gang dance and, in New Orleans, second-lining and Mardi Gras Indian parading. “It was all pretty organic.,” he smiles.

In early August 2005 he arrived in Kentucky where he prepared and collated information and contacts. At the end of August he reached New Orleans, just after Hurricane Katrina struck on 29 August and just before the next strike. He had taken advice from, amongst others, Mike Seeger. Talking at the Q&A after the film’s premiere in October 2006, he recalls that Fats Waller’s was the first dance music that set his bones dancing and dry-mouths it was a piquant, bittersweet moment. His footage of streets devastated by Katrina’s stops at the ruined building that housed Fats Waller’s publishing company. It ends though as it began, enthused by dance music and dance.

A one-man film crew, Reuben began filming on the North Carolina leg with a HDV camera rigged to the side of the car so he could film road miles hands-free while driving. He also developed a two-handed filming technique with hand-held camera in one hand and microphone in the other. “I’m not always pointing the microphone the same place I’m pointing the camera,” he grins. “I tried to make the sound move, as if I’m drawing or painting in space. That’s why you get those variations in sound. Which I deliberately tried to do. I’m not interested in getting sound like you’d get from a mixing desk in a normal concert.”

Routes consciously builds on earlier work, whether David LaChappelle’s dance film Rize or Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music. He is aware of the baton thrust into his hand. Asked about the Harry Smith connection, he replies, “People think he was an anthropologist in that collection. When I looked into it and really listened to the reissue all the way through, I heard it completely differently. The Anthology is much more an artist’s project. For example, he was an expert on American Indian culture but there’s no American Indian music in the project, so it’s clear that he wasn’t out to make an anthropological study of all the music in the States.” A discussion ensues about Smith’s ethno-narcotic journeying.

“He was making a very personal connection between all those sounds. When I heard it, he programmed it like a DJ would select the set. It’s really like that. It really moves and builds to a climax. He’s categorised it. I wanted to collect dance and music in the same way that he wanted to collect songs. He thought it was going to be lost and die out. He used the term globalisation, which was interesting. Back then in the 1950s he used it. Which, of course, as we know, it hasn’t. I wanted to collect it in relation to dance.”

Routes contains the most eidetic dance sequence I’ve ever seen, courtesy of the Melrose Golden Girls. They are a bunch of split-second choreographed black cheerleaders performing krump moves like wide-eyed, psychedelised meerkats out of Mati Klarwein’s Annunciation, the painting that adorned the cover of Santana’s Abraxas album. Most people would have seen them as nothing more than a sideshow at a sports fixture. Reuben captures their perfection. The Melrose Golden Girls burn into the retina like nothing less than the hot sauce of community culture. From North Carolina to Louisiana, Routes captures a cosmopolitan, multi-racial, community-based America, the existence of which we forget at our peril. This is another sort of Americana. And one I can relate to.

A variant of this piece first appeared in fRoots issue 300. www.frootsmag.com

Photograph courtesy of Alex Reuben.

More at www.alexreuben.com

14. 2. 2009 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] It is October and the time of the season that has nothing of the Zombie or indeed Golem about it. Sitting in U Zavěšenýho, one of Prague’s minor miracles of a watering hole a stone’s throw from the castle, I am writing up notes about Prague’s MOFFOM (Music on Film Film on Music) festival. Loquacious as ever, I get into conversation with a French student from Grenoble. She is studying cinema in the city and studying film in this city makes total sense. Learning that I am working at the festival, we exchange viewing plans. Half an hour vanishes just talking about film and Prague’s cinemas. Her boyfriend has come from France to partake too. I leave them with a jaunty tourlou, a toodlepip, and carry off some wonderful insights into another cinéaste or cinephile nation’s appreciation of what we call in Czech pukka kino (‘true cinema’).

14. 2. 2009 |

read more...

« Later articles

Older articles »

[by Ken Hunt, London] Planning a trip to England, Scotland and/or Wales? Hoping your visit coincides with some musical adventures? The highly recommended Spiral Earth guide is the ideal place to start planning your time and trip.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Planning a trip to England, Scotland and/or Wales? Hoping your visit coincides with some musical adventures? The highly recommended Spiral Earth guide is the ideal place to start planning your time and trip. [by Ken Hunt, London] The year started brilliantly, thanks to the Carolina Chocolate Drops and Emily Portman. Then nothing much seemed to happen for the longest while – well, a month or so – and then the sluice gates opened and a wonderful year’s musical experiences began pouring out. It did, however, prove a disappointing year for quality new recordings of Indian music.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The year started brilliantly, thanks to the Carolina Chocolate Drops and Emily Portman. Then nothing much seemed to happen for the longest while – well, a month or so – and then the sluice gates opened and a wonderful year’s musical experiences began pouring out. It did, however, prove a disappointing year for quality new recordings of Indian music. New releases

New releases Historic releases, reissues and anthologies

Historic releases, reissues and anthologies Events of 2010

Events of 2010 [by Ken Hunt, London] London’s National Portrait Gallery is currently offering two marvellous exhibitions of Indian art. Admission is free and while they may not appear to cast much light of the subcontinent’s musical arts, amid the huqqa smokers, the military figures, nobility and royalty, there are a few correlations between Indian portraiture and aspects of the subcontinent’s music to interest the musically minded.

[by Ken Hunt, London] London’s National Portrait Gallery is currently offering two marvellous exhibitions of Indian art. Admission is free and while they may not appear to cast much light of the subcontinent’s musical arts, amid the huqqa smokers, the military figures, nobility and royalty, there are a few correlations between Indian portraiture and aspects of the subcontinent’s music to interest the musically minded. This is in contrast to the Rajasthani portrait called ‘A lady playing a tanpura’ from around 1735 “in ink, gold, opaque and transparent watercolour on paper”. She is unidentified, her features a cipher of the Indian Everywoman. The portrait is all the better for that. Her hair is long and cascades from beneath a bejewelled and pearled turban. She holds her five-stringed tanpura upright (only four tuning pegs are visible). This way she stands for generations of anonymous musicians or nautch entertainers whose features and names are long forgotten. It is on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fletcher Fund. It is a real find. It is available as a postcard.

This is in contrast to the Rajasthani portrait called ‘A lady playing a tanpura’ from around 1735 “in ink, gold, opaque and transparent watercolour on paper”. She is unidentified, her features a cipher of the Indian Everywoman. The portrait is all the better for that. Her hair is long and cascades from beneath a bejewelled and pearled turban. She holds her five-stringed tanpura upright (only four tuning pegs are visible). This way she stands for generations of anonymous musicians or nautch entertainers whose features and names are long forgotten. It is on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fletcher Fund. It is a real find. It is available as a postcard. [by Ken Hunt, London] March’s stuff and nonsense comes from Mickey Hart and chums, Joni Mitchell, The Carolina Chocolate Drops, Bob Bralove and Henry Kaiser, Wajahat Khan and the Medici String Quartet, The Six and Seven-Eights String Band, Jo Ann Kelly, Dillard & Clark, Farida Khanum and Sohan Nath ‘Sapera’.

[by Ken Hunt, London] March’s stuff and nonsense comes from Mickey Hart and chums, Joni Mitchell, The Carolina Chocolate Drops, Bob Bralove and Henry Kaiser, Wajahat Khan and the Medici String Quartet, The Six and Seven-Eights String Band, Jo Ann Kelly, Dillard & Clark, Farida Khanum and Sohan Nath ‘Sapera’. A long-running email dialogue with a rather special vocalist planted Help Me in my head and then the song kept rattling around. Potentially, Help Me is ghazal-like in its layered ambiguity. On hearing Help Me at the time of its release, it had seemed very much a woman’s song. Then under the influence of Iqbal Bano and Farida Khanum and a nazm here and a ghazal there, I got to thinking about how gloriously open to re-interpretation Help Me could be, once going beyond the tale of one of Joni Mitchell’s romances that failed to work out. And more importantly, how it might be twisted to reveal new facets and ambiguities with a further turn or two.