Lives

[Ken Hunt, London] The satirist-songmaker and mathematician Tom Lehrer (1928-2025) was one of a kind. He died on 25 July in Cambridge Massachusetts. Born Thomas Andrew Lehrer in New York City on 9 April, musical theatre and Broadway were in his bloodstream. With his audacious wit and unerring intelligence, he was writing comic, pithy songs by the very beginning of the Fifties.

27. 1. 2026 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The English playwright and film and television scriptwriter, Keith Dewhurst (1931-2025) died on 11 January 2025. He was responsible for a number of important plays performed in the National Theatre. He brought Flora Thompson’s trilogy Lark Rise to life for the stage as Lark Rise and Candleford,

[by Ken Hunt, London] The English playwright and film and television scriptwriter, Keith Dewhurst (1931-2025) died on 11 January 2025. He was responsible for a number of important plays performed in the National Theatre. He brought Flora Thompson’s trilogy Lark Rise to life for the stage as Lark Rise and Candleford,

27. 1. 2026 |

read more...

“Such a long, long time to be gone

And a short time to be there.” – ‘Box of Rain’, Phil Lesh (1940-2024)

[by Ken Hunt, London] For many years I was a newspaper obituarist writing for The Guardian, The Independent, The Scotsman, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Times. In addition, I wrote obituaries for many folk magazines. A sample would be Folker in Germany, the EFDSS Journal in the UK, Penguin Eggs in Canada and Sing Out! in the USA.

[by Ken Hunt, London] For many years I was a newspaper obituarist writing for The Guardian, The Independent, The Scotsman, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Times. In addition, I wrote obituaries for many folk magazines. A sample would be Folker in Germany, the EFDSS Journal in the UK, Penguin Eggs in Canada and Sing Out! in the USA.

Since Oxford University Press took over what from 2004 became the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, I have written music-related biographical essays, mainly folk-related, for that massive reference work. I have added more folk-related entries than any individual contributor in the work’s history, including contributors from 1885 to OUP taking over the reins. (It’s laborious but searching the site is easily do-able.) 2024 saw the publication of my entry for the rock musician Spencer Davis: ‘Davies, Spencer David Nelson (known as Spencer Davis) (1939-2020), singer, guitarist, and actor’.

I sometimes miss writing obituaries. Sometimes not. I miss writing them especially when I read ‘list obits’ which don’t capture what made their subject tick and their character. So here are some lives remembered, sometimes with memories, of a number of people who coloured my life.

The musician, activist and co-founder of Paredon Records, Barbara Dane (b.1927) was a huge influence. I was asked to write something about her in October 2024 for my friend Garth Cartwright’s substack. This is a slightly longer version:

“Over decades of interviewing people, many blur into a haze. That never applied to Bernice Johnson Reagon of the all-black female unaccompanied ensemble Sweet Honey in the Rock. It was the only time I can remember the (white) press officer being so intimidated by an act they were publicising they did a runner. They were formidable. Bernice was a complete joy and inspiration to interview. She had seen and done so much. She had been a founding member of the Freedom Singers which the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had birthed. She had been in the midst of the civil rights struggle during very – neutral word – fraught times.

“In the second half of the Eighties, research started with paper sources. One way or the other. With a season ticket to Collet’s Record Shop on New Oxford Street in London since my teens, it was inevitable that I went there when researching the interview.

“That was how I discovered Paredon Records. They were probably the most politicised record company of the period in the United States. Barbara Dane and her future husband Irwin ‘Izzy’ Silber co-founded the label. They put out Bernice’s Give Your Hands to Struggle. And that was how Barbara Dane, at one remove, came into my life.

“Over the next decades Barbara surfaced again and again. I remember reading a telling review by Young in the book I reviewed. The book’s title is The Conscience of the Folk Revival. It is a collection of Israel Young’s writings. The fourth piece is a review of the 1959 Newport Folk Festival. He wrote: “Barbara Dane then came on with blues and folk tunes. She made a hit by composing a blues, on the spot, about coming to Newport.” Enough said.

“It was decades before Barbara and I spoke. Exactly why and when we wound up talking is hazy now. Damn, she was feisty. She was a hoot and very, very amusing. I remember her talking about her admiration for the English political songwriter Robb Johnson. She positively glowed down the phone when I said we were old friends and drinking companions. To have this woman who was so important for the political song movement singing hosannas about Robb Johnson and Leon Rosselson felt like a fillip. She was indefatigable and inspirational. And at an age when, as they say, ‘she should’ve known better’ she was flamin’ incorrigible.”

The 45s of the Paris-born chanteuse Françoise Hardy (b. 1944) were transfixing. It would be a lie to say she did more for my French than hours of schoolroom lessons and vocabulary tests and conjugating verbs. Her lessons in French popular culture helped to motivate my confidence, though. Beginning with a halting attempt to converse in a Parisian shop, by the end of the Sixties I was chatting to drivers when I hitchhiked through France and Belgium. It was part of the deal to keep them awake. À bientôt, Françoise!

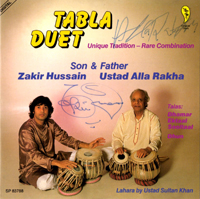

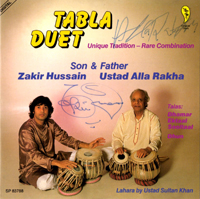

The Hindustani tabla and percussion maestro Ustad Zakir Hussain Qureshi (b. 1951), born a month before me, had been a presence in my musical life for more than ten years before we met in 1981. A child prodigy, he was taught by his father, Ustad Alla Rakha. Hussain’s parents were of Dogra stock. (They would go into Dogri in front of the children when they wanted to discuss something privately.) His dad belonged to the Punjab gharana (school and style of playing) under the tabla virtuoso Ustad Mian Qadir Baksh of Lahore. His father grounded him in its disciplines.

Zakir began performing in public from a young age: “I did my first show when I was seven, so I must have started at least three years before that. I played off and on from about seven to twelve. Then, when I was about twelve or thirteen, I started my professional career.” He went on to work extensively with many of the greatest exponents of the subcontinent’s two classical music systems.

Zakir began performing in public from a young age: “I did my first show when I was seven, so I must have started at least three years before that. I played off and on from about seven to twelve. Then, when I was about twelve or thirteen, I started my professional career.” He went on to work extensively with many of the greatest exponents of the subcontinent’s two classical music systems.

He went on to perform in a range of non-classical fields, notably with the British guitarist John McLaughlin in Shakti and Remember Shakti and Mickey Hart in a variety of ensembles. He was nominated several times for Grammy Awards. He won five. The first two were for Planet Drum and Global Drum Project with Hart. Three were awarded in the final year of his life, including one for This Moment with Shakti.

The first time Zakir and I spoke was as we walked out into the daylight after an all-nighter. He had performed with his dad and the sarangi maestro Ustad Sultan Khan. He said something like “I hear you’ve interviewed my father and Mickey.” And the conversation kept on.

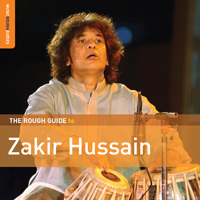

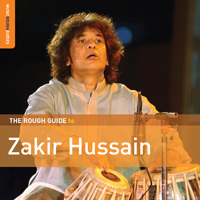

It was an honour to have known Zakir since we were both 30. He brought “new dimensions of eloquence and muscularity to talking in rhythm” (to quote myself from the Rough Guide to Zakir Hussain CD which I compiled and interviewed him for). No chamchagiri, he was one of the most beautiful people, inside and out, I ever met.

The sarodist Aashish Khan (b. 1939), the son of Ustad Ali Akbar Khan and grandson of Ustad Allauddin Khan was one of the young lions who entered the wider discographical imagination with Young Master of the Sarod, released on the World Pacific label or licensed to Liberty. He had the validation of Alla Rakha on tabla. Thanks to his father and his uncle Ravi Shankar, Khan came within George Harrison’s orbit. He appears on Wonderwall Music (1968) and an LP Jugalbandi (1973) on Elektra co-credited to John Barham and Aashish Khan (inevitably) with tabla accompaniment by Zakir Hussain. From talking to him on two occasions, I felt that he was a strangely mixed up fellow. I did not warm to him.

The death of Phil Lesh (b. 1940), the bassist-composer of the Grateful Dead (1965-1995) hit hard. His wide range of musical interests made him a dream interview subject.

Francis McPeake (b. 1942) was a doyen of the uilleann pipes and part of the Northern Irish McPeake dynasty. He was called Francis III for ease of reference. The influence of the McPeakes of Belfast was far-reaching. Their repertoire and performances touched Dylan and the Beatles, Van Morrison and the Byrds.

Ram Narayan (b. 1927) (other spellings of his surname are available) was the first sarangi maestro to elevate the instrument to the concert dais. I regret that I never saw him perform live. That was because he played an enormous part in my Hindustani education. He lit the blue touch-paper to a lifelong love of sarangi in its Hindustani classical, folk, Bombay film industry and qawwali manifestations.

Paredon Records was, as I wrote in the context of Barbara Dane, an important stepping stone in the exploration of the roots of Sweet Honey in the Rock. Their co-founder, the vocalist Bernice Johnson Reagon (b. 1942) was a Civil Rights activist and scholar. Re-reading our Swing 51 also cast me back to Sweet Honey’s ground-breaking role in placing Deaf politics and activism in their music. The feminist and lesbian music scene championed signing in their concerts.

Happy Traum (b.1938), another Swing 51 (Dark Star and Californian folk magazine Folk Scene) interviewee, was a folk musician whose music affected me deeply. The concerts that the Woodstock Mountains Review, of which he was a member, did in Britain in 1981 were real events. He and his wife, Jane also introduced me to Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky. They came to their hotel, fresh and excited from making a pilgrimage to a site of Blakean interest somewhere in, I seem to recall, Dorset. Ginsberg signed the Happy and Artie Traum LP I had with me which he had written the liner dedication for. Kismet. (Ginsberg and I did a number of interviews in subsequent years. One appeared in Mojo with Ginsberg’s early praise for Beck’s ‘Loser’ filleted out. A signed photo of Ginsberg dated “6/18/90” looks down on me on the office wall.) Happy and I kept in touch. He assisted me when I wrote the obituary of his brother Artie Traum for the Guardian in July 2008.

Happy and I resumed our public conversation in interview form in 2018 when I brought him and his old friend from the Greenwich Village days, Bonnie Dobson together for a chinwag for an end-of-life article for fRoots. Afterwards we went for a meal and it was a completely joyous occasion. At his Cecil Sharp House Q&A, asked about him ever distilling this life in print. Perhaps in an ‘Autobiography’ like Dylan’s Chronicles. He replied along the lines of the previous day. “A lot of people – including Jane – have been after me to do it. A couple of people have wanted to do it with me, to be my co-author, that kind of thing. I do have memories but I don’t know if I have enough to really fill out a book and I don’t know if my story is enough to interest people.” It would have and let’s hope he did get something down.

The bluegrass mandolinist Frank Wakefield (b.1934) was one of my wilder interviews. This was thanks to his idiosyncratic style of speech which translated badly to the printed page.

I didn’t learn of the death of Fun-Da-Mental’s Dave Watts in October on Tenerife, Spain until December. Dubbed rather imprecisely the “Asian Public Enemy”, they were ferocious. Aki Nawaz aka Propa-Gandhi had co-founded Fun-Da-Mental in 1991. In solidarity Dave Watts took the stage name Impi-D when he joined. Together they were at the group’s core.

I programmed Fun-Da-Mental as part of the 1997 Rudolstadt Festival in Germany. Back then it was Tanz&FolkFest Rudolstadt, a dance and folk festival. One of the 1997 festival’s Schwerpunkte (focuses) was the year’s regional one commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of India’s self-rule with music and wider arts. 1947 also marked Pakistani Independence from Britain. Enter Fun—Da-Mental.

The raw power of their performance was something else. Watching the reaction to them only felt like a vindication much later once the mushroom cloud had blown away. It polarised. The figurativejout ‘old folks’ were bewildered or shocked. The younger audience was ecstatic and got them. In 2015 the festival produced a limited edition 25th anniversary triple LP set. Fund-Da-Mental’s ‘Ja Sha Taan’ closed Side E. The track had been picked to represent 1997. According to the liner notes, for some, they were Żzu laut, zu roh, einfach unpassend für ein braves Folkfest® (‘too loud, too raw, simply unsuitable for a decent folk festival’). Non, je ne regrette rien. Fun-Da-Mental and its hip hop and sampling bump-started the festival into future worlds. At one point on the way to interviewing Dave I bumped into a friend by the name of Michael Ince in Notting Hill. They were both of British-Bajan (Barbados) stock. Seemed natural to ask Michael if he fancied tagging along. Such a great chinwag. Do get in touch, Michael, if you read this.

Two close friends died in 2024. Chris and Paul were a gay couple. While I was working in Leeds in 1993, I lived with them in Wheldrake, a village 11 km south-east of York. Chris England died in April and Paul Durose in December.

“The dead don’t die. They look on and help.” – D. H. Lawrence, The Letters of D. H. Lawrence: Volume 3, October 1916-June 1921 (1984)

30. 12. 2024 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] John Barlow became a cyber-guru and free speech advocate but when I first got to know him some – thanks to Eileen Law in the Grateful Dead office in the early 1980s, he was the second lyricist for San Francisco’s Grateful Dead. He wouldn’t have bleated about that that.

[by Ken Hunt, London] John Barlow became a cyber-guru and free speech advocate but when I first got to know him some – thanks to Eileen Law in the Grateful Dead office in the early 1980s, he was the second lyricist for San Francisco’s Grateful Dead. He wouldn’t have bleated about that that.

In late 1979 the opportunity arose to interview the Grateful Dead’s principal lyricist Robert Hunter. He was then living with Christie and their son Leroy in an apartment in a street between Earl’s Court tube station and the Troubadour on Old Brompton Road. The in-depth interview, then the longest he had ever had published, eventually stretched across three issues of the magazine Dark Star. Back in San Francisco it was received very well. It lifted the latch. Extensive interviews with key members of the band became a letter away. A priority was the dash to do the first in-depth interview with John Barlow (yet to be billed as John Perry Barlow), The first fruits of their writing collaboration with Bob Weir appeared on Weir’s 1972 studio album Ace, solo-credited even although the whole band was on it and it debuted their new line-up on disc.

Hunter had explained, “With Weir, we spent a lot of time working on things, but I don’t think that we basically satisfy each other. He’s not that nuts about my approach to imagery. He doesn’t want it to be thick he wants it to be lighter and more obvious. He’s not trying to be in the least cryptic. He wants it to be very accessible. We’ve turned out some really good material, but our heads aren’t that together. We want to work together and every now and again we do, but it doesn’t really click.”

Transatlantic phone calls were prohibitively expensive. The future cyber champion and I did the interview the new-fangled way. I sent questions, cassettes and International Reply Coupons – early international currency of choice, continually recycled, rarely cashed in at post offices – and in due course Barlow’s revealing, self-effacing and lengthy interview popped through Swing 51‘s letter box in Sutton, Surrey. He called Hunter “a real poet”, “the genuine article” and continued, “It’s as difficult for Hunter to write in a literal vein as it would be for Wallace Stevens or T.S. Eliot. And Bobby likes his imagery ;concrete. He wants everybody out there to understand it they don’t of course. But that’s what he’s shooting for a lot of the time, so he rebels when I try to slip in something that’s a little vaporous, which I personally would prefer to do more often because, while I’m not the poet Hunter is, I would rather have my songs be poetry.”

The Grateful Dead only ever had one Top 10 song in their three-decade lifespan between 1965 and 1995 – and afterlife – and the Dead did not care a jot. If anything, Touch of Grey, written by the core team of Jerry Garcia and Bob Hunter, was an aberration, a minor liability and on several levels something they did not need. With their ultra-loyal, cross-generational following known as Deadheads, hit singles and chart activity never troubled them. While many wrote them off, knee-jerk fashion, scorning them as psychedelic slackers, they had a prodigious song output, to which Barlow contributed his part as lyricist especially and principally for Bob Weir. In the doing, they created a wrong-headed, alt business model. It has since been celebrated in popular economics textbooks. One, David Meerman Scott and Brian Halliagn’s Marketing Lessons from the Grateful Dead (2010), summarised it with populist, hippie stereotype transcending maxims like “Bring People on an Odyssey”, “Build a Diverse Team”, and “Encourage Eccentricity”.

John Perry Barlow was born in 1947 in Jackson Hole, Sublette Co., Wyoming, the only child of the Republican state legislator Norman Barlow and Miriam Barlow Bailey (née Jenkins). A far cry from the citified bohemian ways of the Bay Area-based Grateful Dead, on the face of it Barlow’s upbringing was the living antitheses of this psychedelic rock group’s ethos. His embraced a staunchly Republican frontier spirit, the Mormon Church, Boy Scouts, freemasonry and a life lived in the vicissitudes of cattle ranching on the Bar Cross Land & Livestock Company in Cora. Wyoming’s subarctic climate produces long snow-bound, freezing winters and short, cool summers. “What we talk about around here,” he once said, “is cattle prices and the weather. And primarily the weather. [.] We’re out in it all the time. We tend to regard life as a prank played on us by God, with his best instrument being the weather.” The elements duly figured in Weir/Barlow songs such as Cassidy, Looks Like Rain and Weather Report Suite.

Barlow became a difficult child, a “jack Mormon” and his father, he explained in his first major interview anywhere in Swing 51 in 1984, “was told it was best to get me sent away if he wanted to go on running for office.” He was duly sent to a prep school called Fountain Valley in Colorado Springs where he first met a fellow outsider called Robert Hall Weir, thirteen days his junior. “The school functioned largely for kids with behavioural difficulties, not in a clinical sense, but it was a pretty open-minded place,” he continued. Deemed misfits, “the upper classmen singled us for particular Hell, Weir more so than me fortunately, but we both took a fair amount of shit.” Barlow and Weir, a dyslectic, adopted child from the middle-class suburb of Atherton, California and already a serial school expulsion specialist, formed a deep and abiding, lifelong bond.

Later in college Barlow’s thesis advisor – “an eminent American writer” – took his honours thesis work to the publisher Farrar, Straus & Giroux who bought an option on The Departures. With the “fairly sizeable” advance, “having just gotten out of the draft and out of college” he went to India for about five months. He finished it in an abandoned wintertime beach town called Clinton, Connecticut on Long Island Sound. The first section and the newly written second half never worked, let alone dovetailed, and that was that. It was, he recalled in that Swing 51 interview, “a picaresque fantasy about America and our old yearning to be ever on the cutting edge of a frontier. It was about a people who need frontiers running out of them.” He continued to write, including journalism such as reviewing the BMW R75 for Motor Cycle Magazine. He later would gain extensive experience of giving testimonials to Congress on such weighty matters as Wilderness, Non Point Source Water Pollution, Acid Rain and the Grizzly Bear.

Back in California, Garcia was eager to encourage Weir’s songwriting. The youngest of the Grateful Dead’s founding fathers, Weir was a knotty, strongly opinionated individual. He had contributed as a co-writer to the That’s It For The Other One suite, first commercially released in 1968 on the Anthem of the Sun album. He too gravitated to Hunter as a source of words, collaborating, for example, on ‘Sugar Magnolia’ and ‘Playing In The Band’. But it was a relationship rendered artistically fraught by Weir’s lyrical interventions. Barlow stepped into the breach.

It fell to him to take over running the ranch in 1971. One of his wife Elaine Parker’s photographs shows him as a prototypical cowboy rancher: bearded, sunshaded, dressed for the weather in cowboy hat, quilted windcheater and leather chaps emblazoned with the Bar Cross brand, carrying a bale of hay in one hand and a baling hook in the other. 1971 was smack dab in the middle of the Dead hitting a purple patch between 1970 and 1972. During this peak period of creativity, Weir’s first solo album Ace appeared. A solo album in name only, it featured the entire mothership’s line-up, including the new kids on the block, keyboardist Keith and vocalist Donna Godchaux. It became the band’s de facto studio album of 1972. It also unveiled the new Weir/Barlow partnership, evidenced by Black-Throated Wind (written in India and the source of the title of Mother American Night: My Life in Crazy Times, Barlow’s memoir written with Robert Greenfield, to be published in 2018), Walk In The Sunshine, Looks Like Rain, Mexicali Blues and Cassidy. Though fewer numerically, the Weir/Barlow partnership went on to produce more substantial additions to the canon than any other writing partnership outside of Garcia/Hunter.

Cassidy, a lyric he wrote to an existing rhythm guitar part (rather than their more usual approach of Weir setting words), describes a welcoming and an adieu. Cassady, Barlow’s preferred (but overridden) personal spelling, was “a wave goodbye to Neal and a hallo to Cassidy”. Neal Cassady was the hero of Kerouac’s On The Road, a former Merry Prankster and the “cowboy Neal/At the wheel/Of a bus to never-ever land” of the That’s It. suite. Cassidy was the daughter of Eileen Law who “gave birth to [.] out there at the Rucka Rucka Ranch [in Marin Co., California] shortly after the time Neal Cassady died”. (At the time Law was much taken with the film Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid.) Both mother and daughter remained ever after members of the extended Dead family. The camaraderie and brotherhood of the organisation – whether the people who stood on stage, the lyricists who wrote the words, the graphic artists who painted and designed, the lighting and sound engineers – was and remains sui generis. Yet despite the new revenue stream of royalties, the Bar Cross, in the family since 1907, did eventually go under, as the feared “wholly-owned subsidiary of the Rock Springs National Bank”.

Barlow was an intensely humorous man whose conversation was peppered with drollery and deadpan asides and whose anecdotes could be devastatingly self-deprecating. An early cyber visionary, he popularised the term cyberspace, an expression he borrowed from William Gibson who coined it in his 1982 short story Burning Chrome and further promulgated it in his 1984 science fiction novel Neuromancer. Barlow was an early advocate of The WELL – short for Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link – one of the earliest virtual communities, founded in 1985 by the epidemiologist and technologist Larry Brilliant and the early LSD adventurer, Merry Prankster and Whole Earth Catalog visionary Stewart Brand. In July 1990 the month the Dead’s longest-serving keyboardist Brent Mydland with whom Barlow also wrote, died, Barlow, Mitch Kapor and John Gilmore co-founded the Electronic Frontier Foundation. This was a San Francisco-based, not-for-profit, digital rights group designed to promote civil liberties and champion free speech on the web. Collectively, EFP foresaw the potential of social media and the possibilities of bulletin boards were barely appreciated. It remains one of Barlow’s enduring legacies.

He died at his San Franciscan home of undisclosed causes. His 1977 marriage to Elaine Parker ended in separation after 17 years in 1992 and divorce. His survivors include his daughters, Amelia, Anna and Leah. His fiancée, Dr. Cynthia Horner, died in 1994.

John Perry Barlow, cyber-guru, free speech advocate and lyricist, was born on October 3, 1947. He died on January 6, 2018, aged 70

30. 7. 2018 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London and Jalandhar] Visiting Nek Chand’s life’s work known as the Rock Garden of Chandigar – the union capital of the Indian states of Haryana and Punjab – must have once felt like being somewhere in a gigantic a work in progress. Since his death on 12 June 2015 at the age of 90 – and speaking more romantically – his Rock Garden of Chandigarh entered another phase.

[by Ken Hunt, London and Jalandhar] Visiting Nek Chand’s life’s work known as the Rock Garden of Chandigar – the union capital of the Indian states of Haryana and Punjab – must have once felt like being somewhere in a gigantic a work in progress. Since his death on 12 June 2015 at the age of 90 – and speaking more romantically – his Rock Garden of Chandigarh entered another phase.

It will now be a tourist attraction forever in a state of maintenance – and not in a bad sense. Even though it had long been in a state of constant maintenance – with major and minor repairs, cleaning and polishing occurring day in, day out – that won’t finish as long as people appreciate it. The English gardener Monty Don describes as “the best garden story in the history of the world” in his television series Around the World in 80 Gardens. Nek Chand’s creation is a place to make anyone re-calibrate their head.

Nek Chand built it quietly, surreptitiously in a quiet corner of Chandigarh using discarded and dumped stuff. Stuff is the operative word. He used broken crockery, broken bangles, electrical components, vitreous china, weather-beaten rocks and leftover masonry and miscellaneous junk to create something both otherworldly and nearly of this world. The gardens are populated with figures in human and animal form going about their everyday activities, gawking at visitors or ignoring them.

Nek Chand built it quietly, surreptitiously in a quiet corner of Chandigarh using discarded and dumped stuff. Stuff is the operative word. He used broken crockery, broken bangles, electrical components, vitreous china, weather-beaten rocks and leftover masonry and miscellaneous junk to create something both otherworldly and nearly of this world. The gardens are populated with figures in human and animal form going about their everyday activities, gawking at visitors or ignoring them.

Nek Chand Saini was born on 15 December 1924 in Barian Kalan, a village which became Pakistan after Partition and which he trekked on foot to escape from in 1947. He became a government road inspector in due course but on the quiet he began building something unique, in the true sense of the word, squirreled away in what is regularly described as the Chandigarh jungle

That is one very good reason for including it on a predominantly music website. For me, Chand’s found-art is a visual parallel of Bollywood music.

His obituary appeared in The Times of 17 July 2015, page 54. John Maizels’ obituary in the Guardian appears here https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/jun/15/nek-chand

All images © 2017 Ken Hunt/Swing 51 Archives

11. 3. 2017 |

read more...

J P Bean

J P Bean

Faber & Faber

ISBN 978-0-572-30545-2

[by Ken Hunt, London] Britain’s folk clubs must seem strange to anyone visiting them for the first time. They are an exceedingly British institution, only found on English, Northern Irish, Scottish and Welsh soil – or, allowing for poetic licence, on foreign soils as British forces’ transplants, such as RAF Luqa’s Malta Folk Club and the British Army on the Rhine. To interject a personal observation, the folk club equivalents in Eire, Germany, the Netherlands, Germany and the USA all have altogether different characters.

It was only in the second half of the 1950s that Britain’s folk clubs started and a coherent folk scene began coalescing. Ironically the English Folk Song & Dance Society had been frantically dance-orientated. Yet before the term ‘folk club’ was coined there were gatherings like Harry and Lesley ;Boardman’s ‘folk circle’ founded around 1954 in Manchester and Alex Eaton’s roughly contemporaneous Workers’ Music Association-inspired gatherings in Bradford. Often overlooked, there were university-based folk societies such as Cambridge’s St. Lawrence Folk Song Society, founded in 1950, and Oxford’s Heritage Society, operating by 1956. Aside from their own such as Stan Kelly and Rory McEwen they also booked occasional guests like Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Shirley Collins.

Arguably the first big stone flung into the pond was the establishment of Ballads & Blues in London. Hosted by Ewan MacColl, with strong support from Bert Lloyd, Isla Cameron, Fitzroy Coleman and Peggy Seeger, it met, most memorably, at the Princess Louise in High Holborn. Re-launched as a club in November 1957 after the Ballads & Blues ensemble returned from Moscow, the ensemble had lent its name to the club. It set so many standards. For example, Jimmie Macgregor, then teaching in Glasgow, would hitchhike from Scotland to London (over 700 miles there and back) to attend the club at weekends. By 1960 Robin Hall and Jimmie Macgregor’s duo would be the television face of folk.

Bearing in mind the importance of folk clubs to the vitality and longevity of the British folk scene it may seem peculiar that J P Bean’s absorbing oral history Singing From The Floor is the first major account devoted to the folk club institution. They were – and remain – the bedrock of the folk scene, the places where many people learned stagecraft and how to hone material or just to have a good evening out and a sing. Before camera-phones and YouTube folk clubs were where musicians unselfconsciously tweaked and road-tested material. J P Bean’s voyage began in 1966 when as a teenager he visited the folk club “above the Three Cranes pub” in his hometown, Sheffield.

You started researching this book in 1966 by going to your first club. What was your reason for going to one?

You started researching this book in 1966 by going to your first club. What was your reason for going to one?

I’d seen a bit on television. I’d seen Alex Campbell and Martin Carthy. I’d heard some pieces on the radio. I was only just 16 and I wanted to know more. I read a snippet in the local [Sheffield] paper about the Barley Mow folk club, so I went along and found this heaving, sweaty, oozy but cheerful Saturday night scene. And like I say in the intro it was like Christmas Eve every Saturday night. I saw people there, the impressions of whom would stay with me all these years.

More specifically, what attracted you?

What it was really that attracted me – it wasn’t just the Saturday night atmosphere or whatever – it was the characters. You know, there were some great characters in the folk clubs. There were people that made a big impression on you. People like Bob Davenport with the way he could hold the audience without any instrumental accompaniment all night long. Alex Campbell was a great character and a comedian but people like [Diz] Disley, Tony Capstick and Billy Connolly I would say I have a fondness for. They were wonderful times and I hope that comes across in the book.

When did you start interviewing people?

I started in April 2010. From the very first interviews with Louis Killen in Gateshead and Martin Carthy in Robin Hood’s Bay, from then to publication was almost exactly four years. The last year there wasn’t much happening because it was pre-production. I spent a good eighteen months roaming up and down the land just interviewing people, chasing them on the phone, getting numbers and networking. Then it slackened off as I started to put it together.

It was a wonderful social time. People welcomed you to their homes or you met them in pubs or you met them wherever. And heard the stories. I heard the stories of people who I’d only sat and marvelled at when I was young.

When looking back over that scene I know in my case I have semi-regrets I didn’t get to talk to certain people. Are there any people you would have dearly loved to have captured?

I would have loved to have interviewed Ewan MacColl. I would have liked to have interviewed Bert Jansch. I missed him by a very short span.

This is the dream. I’d have liked to have talked to Bob Dylan about London ’62/’63. And possibly Paul Simon. I wrote to Paul Simon’s management three times but didn’t get a reply. And I wrote to Dylan’s. But there are so many people who knew them at that time and presented a different angle or a different view on how they saw them – Dylan and Simon – that I think it really works out alright.

Did you ever go to any folk clubs outside of the British Isles?

Only Jersey [one of the Channel Islands between England and France]. And I don’t think that would count.

No, I didn’t and I would always have liked to have done. In those days when I was younger I would have loved to have gone to America or Canada. I didn’t get to American until ’94 and that was through doing the Joe Cocker book [Joe Cocker – The Authorised Biography, 1990, revised 2003].

Did you get any sense of impermanence at the end of the book you know, the way things have changed in the folk club scene?

How do you mean?

Well for instance, you talked about going along to the Barley Mow at the Three Cranes. Is the Three Cranes pub still there?

Yeah.

See, where I live [in southern England] pubs have just disappeared and most of the clubs were in pubs.

Most of the pubs in the Sheffield/South Yorkshire area where the folk clubs were held are still standing. They don’t all bear the ;same name. One of the big ones was the Highcliffe that is a very thriving gig now called the Greystones. The Highcliffe Folk Club was the first place in England where Billy Connolly, Barbara Dickson and John Martyn played, brought down by Hamish Imlach.

Years ago I went for a walk, as I used to do quite regularly, with Gill Cook [the doyen of Collet’s folk emporium in New Oxford Street] and I remember we did this walk – it was a ‘research pub crawl’. She talked about all the folk clubs in this little area of Soho in London. There were some in cellars and some in the top rooms of pubs. It was fascinating.

As you describe that this is exactly the reason I did Singing From The Floor. I wanted to get as many of those stories as I could. Gill Cook had died by that time. I was aware when Alex Campbell went that he must have had so many great stories because he’d played so many clubs, busked on the streets.

The one interview that sticks in my mind and it does pertain to Transatlanticness was sitting in a pub in Islington with Tom Paley. He was in his 80s at the time. He was talking about playing union hall gigs with Woody Guthrie and how Woody used to take him round to Leadbelly’s house on a Sunday afternoon. That was like touching history.

A lot of it was with a lot of people in England and Scotland but that with Tom Paley, for me, was quite amazing.

Julian Broadhead alias J P Bean died in late 2015. His obituary is here http://www.thestar.co.uk/news/sheffield-writer-j-p-bean-dies-aged-66-1-7560561#axzz3r5FvhJ4Z

Ken Hunt’s obituary of Gill Cook is here:

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/gill-cook-341453.html

19. 2. 2016 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] In 1955 North America’s modern-era fascination with Hindustani music began with the advent of jet travel and the arrival of the sarod maestro Ali Akbar Khan in New York. By then, Shamin Ahmed Khan, born in Baroda, Baroda State (modern-day Gujarat) on 10 September 1938, had already met the musician who would transform his life.

[by Ken Hunt, London] In 1955 North America’s modern-era fascination with Hindustani music began with the advent of jet travel and the arrival of the sarod maestro Ali Akbar Khan in New York. By then, Shamin Ahmed Khan, born in Baroda, Baroda State (modern-day Gujarat) on 10 September 1938, had already met the musician who would transform his life.

In 1951 he met Ali Akbar Khan’s brother-in-law, Ravi Shankar. Shamim Ahmed belonged to a family of hereditary musicians of the Agra Gharana. A gharana is a school and style of Hindustani classical music historically rooted in a specific place – Agra is in modern-day India’s northern state of Uttar Pradesh. A boyhood bout of typhoid destroyed his singing range. He switched to sitar.

In December 1955 he met Shankar again in Delhi while attending an All India Radio music competition. Shankar was the Music Director of AIR’s Vadya Vrind Chamber Orchestra and invited Shamim Ahmed and his father, the classical vocalist Ghulam Rasool Khan to his Delhi residence. The 17-year-old’s playing impressed him so much that that month they formally ‘tied the thread’ – ganda bandan – that symbolically connected them as guru and shishya (disciple-pupil).

As one of Shankar’s first shishyas, he ‘commuted’ the 1000 km between Baroda and his guru’s home. When he moved to Bombay in 1960, Shamim Ahmed relocated to fill a teaching position at Shankar’s Kinnara School of Music. In 1968 Shankar invited him to California to be one of the young lions on what became immortalized as Ravi Shankar’s Festival From India (World Pacific, 1968; BGO Records [reissue], 1996) – the sitar and sarod duet on rāg Kirwani with Ali Akbar Khan’s eldest son, Aashish Khan is one of the double-LP’s highlights.

As one of Shankar’s first shishyas, he ‘commuted’ the 1000 km between Baroda and his guru’s home. When he moved to Bombay in 1960, Shamim Ahmed relocated to fill a teaching position at Shankar’s Kinnara School of Music. In 1968 Shankar invited him to California to be one of the young lions on what became immortalized as Ravi Shankar’s Festival From India (World Pacific, 1968; BGO Records [reissue], 1996) – the sitar and sarod duet on rāg Kirwani with Ali Akbar Khan’s eldest son, Aashish Khan is one of the double-LP’s highlights.

The same period saw him guest on the Indo-jazz fusion project Rich á la Rakha (World Pacific, 1968; BGO Records [reissue], 2001), fronted by Shankar’s tabla virtuoso Alla Rakha and the US jazz drummer Buddy Rich. He also recorded his US solo debut Monitor Presents India’s Great Shamim Khan: Three Ragas (Monitor, undated; Smithsonian Folkways Archival, 2007) with the student prince of tabla Zakir Hussain accompanying.

As a senior Shankar shishya, he graced the triple-CD ShankaRagamala – A Celebration of the Maestro’s Music by his Disciples (Music Today, 2005) superbly interpreting his guru’s raga composition Janasanmodini. That December 1955 ceremony in Delhi created a life-long, mutual commitment and steered a superlative, sweet-voiced sitarist’s seven-decade career in music. He died in Mumbai, Maharashtra on 14 February 2012.

Shamim Ahmed Khan holds a special place in my heart. I took my young son Tom to one of his recitals, organised by the promoter Jay Viswa-Deva. Afterwards Shamim and I talked at length and he entreated me to pass my opinion of his performance to his guru. The recital was memorable for another reason. Tom and I fell into conversation with a charming woman. She was friendly and so attentive when it came to my lad. When I got home I related what had happened to my wife, Dagmar. The kind woman was the actress Vanessa Redgrave. Tom was aged under ten and had no idea who was talking to him so attentively.

Shamim Ahmed Khan holds a special place in my heart. I took my young son Tom to one of his recitals, organised by the promoter Jay Viswa-Deva. Afterwards Shamim and I talked at length and he entreated me to pass my opinion of his performance to his guru. The recital was memorable for another reason. Tom and I fell into conversation with a charming woman. She was friendly and so attentive when it came to my lad. When I got home I related what had happened to my wife, Dagmar. The kind woman was the actress Vanessa Redgrave. Tom was aged under ten and had no idea who was talking to him so attentively.

Ken Hunt’s obituary of Shamim Ahmed Khan appeared in The Independent of Tuesday 6 March 2012.

All images are courtesy of Swing 51 Archives.

31. 10. 2015 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] At the time of the inspirational illustrator Maurice Sendak’s death, obituaries concentrated on his connections with Mozart, Prokofiev, Janáček and suchlike. On the occasion of the death of the US folksinger Jean Ritchie (1922-2015), it is time to remind about his bigger sound palette connections, notably one that coloured his early art. One commission revealed other musical tastes.

[by Ken Hunt, London] At the time of the inspirational illustrator Maurice Sendak’s death, obituaries concentrated on his connections with Mozart, Prokofiev, Janáček and suchlike. On the occasion of the death of the US folksinger Jean Ritchie (1922-2015), it is time to remind about his bigger sound palette connections, notably one that coloured his early art. One commission revealed other musical tastes.

Sendak illustrated one of the most important, early books of the US Folk Revival, Jean Ritchie’s Singing Family of the Cumberlands (1955). Ritchie, the book reminds, “born in Viper, Kentucky, in the Cumberland Mountains” in 1922, was an authentic voice whose repertoire like ‘The Cuckoo She’s A Pretty Bird’ traversed folk into rock – to Janis Joplin, for example – and maybe even into R&B with Inez & Charlie Foxx’s Mockingbird – a take on the traditional Hush Little Baby. Shady Grove? A version appeared in Ritchie’s book.

Sendak provided line illustrations for each of the book’s 13 chapters. They capture an emergent style. Some are flimsy-flitty.

Others prefigure a style to which he would return with The Juniper Tree and Other Tales from Grimm (1973). Singing Family of the Cumberlands provided him with a pictorial realm blurring folk song and folk tale and opportunities to use quasi-psychological imagery – notably face-to-the-wall oddness – and depictions of marriage juxtaposed with constrained livestock, square dancing and rocking the cradle. Many of the book’s illustrations are dry runs for what came later. We must hope that when art historians get their teeth into his legacy, his folk legacy will be better appreciated.

Jean Ritchie’s Singing Family of the Cumberlands illuminates so much. In 1955 folk music carried so many proletariat and radical associations. Hard to imagine after so many decades but Singing Family of the Cumberlands is still in print, most recently with the University Press of Kentucky in 1988, though that may now be outdated. That edition is still around.

The author’s obituary of Jean Ritchie published in the ‘paper’ edition of The Independent of 5 June 2015 is at: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/jean-ritchie-served-as-inspiration-for-bob-dylan-shirley-collins-and-joni-mitchell-10298307.html

8. 6. 2015 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] It is a knee-jerk reaction when evoking Belgian song to extol Jacques Brel and his impact on Francophone chanson. But Belgium is a composite nation, with Walloon, Flemish and German populations. When it comes to articulating what it means to be Flemish, one of the giants of contemporary Flemish song and poetry was Wannes van de Velde, who for more than 40 years defined Flemish culture and defied cultural laziness.

5. 4. 2015 |

read more...

Lubomír Dorůžka (1924-2013)

[by Ken Hunt, London] One of Europe’s foremost jazz critics, of a status comparable to Nat Henhoff in the States, died on 16 December 2013 in Prague. Lubomír Dorůžka rose to become the preeminent Czech-language jazz historian in Czechoslovakia and, after the separation in 1993, the Czech Republic. He was a Czech musicologist, music historian and critic (not just jazz), author, literary translator (including, naturally, the Jazz Age writings of F. Scott Fitzgerald and William Faulkner, amongst others) and much more. Lubo Dorůžka had the ill-starred fortune to be a jazz aficionado under two totalitarian regimes, during periods when to call jazz dangerous was an understatement.

[by Ken Hunt, London] One of Europe’s foremost jazz critics, of a status comparable to Nat Henhoff in the States, died on 16 December 2013 in Prague. Lubomír Dorůžka rose to become the preeminent Czech-language jazz historian in Czechoslovakia and, after the separation in 1993, the Czech Republic. He was a Czech musicologist, music historian and critic (not just jazz), author, literary translator (including, naturally, the Jazz Age writings of F. Scott Fitzgerald and William Faulkner, amongst others) and much more. Lubo Dorůžka had the ill-starred fortune to be a jazz aficionado under two totalitarian regimes, during periods when to call jazz dangerous was an understatement.

He was born on 18 March 1924 in what was then Czechoslovakia’s capital, Prague. Growing up, he bore witness to Czechoslovakia – after 1933 the last remaining parliamentary democracy in central and eastern Europe – pressured into ceding territory. That began so fatefully with Nazi Germany’s annexation of the Sudetenland in late 1938.

Anyone caught listening to swing jazz during the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia or France could expect imprisonment and possible internment or death in concentration camps. Loving jazz and the freedoms it represented was dangerous. Mike Zwerin (1930-2010), in his 1985 book La Tristesse de Saint Louis: Swing Under the Nazis (‘The Sadness of Saint Louis’), calls this music “a metaphor for freedom”. The Nazis labelled it more robustly “degenerate music”.

The Monica Ladurner film Schlurf – Im Swing gegen den Gleichschritt (‘Schlurf – With or in the Swing against the Goosestep’) (Austria, 2007) documents the American swing jazz-loving, underground youth movements in their German, Austrian, French and Czechoslovakian guises in various languages. The derogatory German-language idiom Schlurf, though now it sounds faintly quaintly antique to German ears, came from schlurfen – ‘to shuffle’. The word communicated a world of wastrels, sluts (more correctly Schlurfkatzen) and ne’er-do-wells loitering in the shadows or an alleyway. It’s rather like a precursor of punk. Its subtext said jazz, inferiority and degeneracy. In Germany another movement was the Swing-Jugend (‘Swing youth’). They were fond of substituting ‘Sieg Heil!’ with ‘Swing Heil!’ in the right circumstances. In occupied Czechoslovakia their equivalent movement was the Potápky, literally, great crested grebes. They ducked and dived like those water fowl. And, of course, grebes – great or little – have the habit of resurfacing somewhere other than anticipated.

At a screening of Schlurf. at the Kino Světozor in Prague, where it was running as part of the MOFFOM (short for Music on Film Film on Music) festival in 2009, something unexpected happened. Partway through, Lubo was there on screen talking about the movement and those times. It took a while to click that he was speaking in German – in cultivated, Czech-inflected German – because we had never talked in German. Foolishly, it had never occurred to me that he spoke the language. In fact certainly during occupation part of his schooling had been through the occupier’s language. At the time I was based in Lubo and his wife Aša’s Prague apartment while they were away travelling. I was surrounded by framed photographs (like him with Louis Armstrong), his book collection, memorabilia and the like. It seemed unreal. Between 1944 and 1945 he began writing about swing for a samizdat publication. In the screening I wept in the darkness for Lubo and my father, Leslie Hunt, who was a swing jazz musician, twelve years Lubo’s senior, who throughout the War had been a full-time bandsman with the Royal Air Force, playing the very music that the Nazis hounded.

During the Communist era Lubo became the Czechoslovakia correspondent for major US magazine titles. Jazz was American and the authorities kept an eye on it and anyone peddling it. It meant that he was receiving all manner of US releases for review, including ESP LPs like the Fugs. Czechoslovakia’s earlier official party line, like other Iron Curtain countries, had been that jazz, like blues, was the voice of social struggle, the voice of the oppressed Negro in the United States and so on. In this ghetto jazz was safe and containable. As its popularity grew and its counter-cultural possibilities made themselves apparent, the Czechoslovakian authorities grew wary.

Lubo’s Panoráma Jazzu (‘Panorama of Jazz’) (1990), published during the time of political climate change, covers the standard jazz history and its Czechoslovakian complexion. It includes, say, Jaroslav Ježek and Karel Velebný, but extends to musicians such as Anthony Braxton and David Murray as well as the jazz released on Eastern bloc labels such as Amiga, Melodiya, Muza and Supraphon. His 2002 book Český jazz mezi tanky a klíči (‘Czech jazz between tanks and keys’) (2002) – though klíči has parallel translation possibilities such as ‘musical keys’ and ‘passports’ – is another of his books on the nation’s jazz history. “Between tanks and keys”, his son clarified, refers to the exact time interval between the Soviet tanks in 1968, and the Velvet Revolution in 1989, when crowds at Wenceslas Square rattled their keys as a symbol of resistance.

He and his wife (who died four days after him) came to love Cornwall on the Atlantic tip of England in the period when travel was possible. Into their 70s they would travel overland by coach from Prague to Victoria Coach Station and then on to Cornwall. The freedom to travel was something they prized highly, having spent chunks of their lives when such possibilities were restricted or impossible.

On the day I flew back to London after MOFFOM 2009, I was attending to last-minute matters in the city. The weather turned. Walking to the Metro station at the top of Wenceslas Square, the skies opened up. I had no coat or umbrella. The rain bucketed down and forced me to rush for the shelter of a pub on Krakovská, at the top end of the square but still too far from the entrance to the station to do the dash in the deluge. Waiting out the rain, I started writing a song lyric for the Czech violinist-vocalist Iva Bittová. The film Schlurf and more specifically Lubo’s reminiscing shot with the backdrop of the Kino Laterna got the creative juices going. (Kino Laterna was a wordplay on Kino Lucerna on nearby Vodičkova which had been a backdrop in Schlurf and laterna magika or ‘magic lantern’ theatre.) Two beers later the first draft was done. The rain let up and it was possible, as my father used to say, to dance between the raindrops and head to Muzeum station. Beforehand though, I took stock of where I had been. In the downpour I had spied an inn sign and had simply ducked in.

The pub’s name was U Housliček! I knew enough broken Czech to know that, even if it had any other idiomatic meaning, literally housliček meant ‘little violin’. That seemed auspicious enough for a ‘don’t believe in miracles: rely on them’ moment. Scant hours later I touched down at London Heathrow with a fair-to-finished lyric ready for keying, for sleeping on and then sending off. Titled Kino Laterna, it became part of the repertoire of Checkpoint KBK, Bittová’s US-based trio with clarinettist David Krakauer and accordionist Merima Ključo.

In late May 2013 Lubo, his music critic and broadcaster son, Petr (this website’s Czech co-host) and I attended a concert at Libeňská synagoga in the Libeň district of Prague 8. It was a concert featuring Iva Bittová, his guitarist grandson David Dorůžka, the pianist Aneta Majerová (David’s partner) and the cellist Peter Nouzovský. Lubomír was treated like a dignitary, being addressed by all but family and close friends as Pán Dorůžka where, by tone and reverence, Pán functions more on the Lord side of Mister. I felt myself privileged that for more than 20 years he and I had been Lubo and Ken.

Lubomír Dorůžka may have been an unknown and unsung hero beyond Czech borders but he was one of the greatest champions of jazz of our era. No, back up: he was his country’s and his countries’ Nat Hentoff with an added danger factor.

A shorter version of this tribute was published on Jazzwise‘s website.

The image of three generations of Dorůžkas from Libeňská synagoga on 31 May 2013 is © Ken Hunt/Swing 51 archives

More images, including Lubo and Satchmo, are at https://www.facebook.com/media/set/edit/a.10201182595759547.1073741833.1610003051/

23. 6. 2014 |

read more...

Older articles »

[by Ken Hunt, London] The English playwright and film and television scriptwriter, Keith Dewhurst (1931-2025) died on 11 January 2025. He was responsible for a number of important plays performed in the National Theatre. He brought Flora Thompson’s trilogy Lark Rise to life for the stage as Lark Rise and Candleford,

[by Ken Hunt, London] The English playwright and film and television scriptwriter, Keith Dewhurst (1931-2025) died on 11 January 2025. He was responsible for a number of important plays performed in the National Theatre. He brought Flora Thompson’s trilogy Lark Rise to life for the stage as Lark Rise and Candleford, [by Ken Hunt, London] For many years I was a newspaper obituarist writing for The Guardian, The Independent, The Scotsman, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Times. In addition, I wrote obituaries for many folk magazines. A sample would be Folker in Germany, the EFDSS Journal in the UK, Penguin Eggs in Canada and Sing Out! in the USA.

[by Ken Hunt, London] For many years I was a newspaper obituarist writing for The Guardian, The Independent, The Scotsman, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Times. In addition, I wrote obituaries for many folk magazines. A sample would be Folker in Germany, the EFDSS Journal in the UK, Penguin Eggs in Canada and Sing Out! in the USA. Zakir began performing in public from a young age: “I did my first show when I was seven, so I must have started at least three years before that. I played off and on from about seven to twelve. Then, when I was about twelve or thirteen, I started my professional career.” He went on to work extensively with many of the greatest exponents of the subcontinent’s two classical music systems.

Zakir began performing in public from a young age: “I did my first show when I was seven, so I must have started at least three years before that. I played off and on from about seven to twelve. Then, when I was about twelve or thirteen, I started my professional career.” He went on to work extensively with many of the greatest exponents of the subcontinent’s two classical music systems.  [by Ken Hunt, London] John Barlow became a cyber-guru and free speech advocate but when I first got to know him some – thanks to Eileen Law in the Grateful Dead office in the early 1980s, he was the second lyricist for San Francisco’s Grateful Dead. He wouldn’t have bleated about that that.

[by Ken Hunt, London] John Barlow became a cyber-guru and free speech advocate but when I first got to know him some – thanks to Eileen Law in the Grateful Dead office in the early 1980s, he was the second lyricist for San Francisco’s Grateful Dead. He wouldn’t have bleated about that that. [by Ken Hunt, London and Jalandhar] Visiting Nek Chand’s life’s work known as the Rock Garden of Chandigar – the union capital of the Indian states of Haryana and Punjab – must have once felt like being somewhere in a gigantic a work in progress. Since his death on 12 June 2015 at the age of 90 – and speaking more romantically – his Rock Garden of Chandigarh entered another phase.

[by Ken Hunt, London and Jalandhar] Visiting Nek Chand’s life’s work known as the Rock Garden of Chandigar – the union capital of the Indian states of Haryana and Punjab – must have once felt like being somewhere in a gigantic a work in progress. Since his death on 12 June 2015 at the age of 90 – and speaking more romantically – his Rock Garden of Chandigarh entered another phase. Nek Chand built it quietly, surreptitiously in a quiet corner of Chandigarh using discarded and dumped stuff. Stuff is the operative word. He used broken crockery, broken bangles, electrical components, vitreous china, weather-beaten rocks and leftover masonry and miscellaneous junk to create something both otherworldly and nearly of this world. The gardens are populated with figures in human and animal form going about their everyday activities, gawking at visitors or ignoring them.

Nek Chand built it quietly, surreptitiously in a quiet corner of Chandigarh using discarded and dumped stuff. Stuff is the operative word. He used broken crockery, broken bangles, electrical components, vitreous china, weather-beaten rocks and leftover masonry and miscellaneous junk to create something both otherworldly and nearly of this world. The gardens are populated with figures in human and animal form going about their everyday activities, gawking at visitors or ignoring them. J P Bean

J P Bean You started researching this book in 1966 by going to your first club. What was your reason for going to one?

You started researching this book in 1966 by going to your first club. What was your reason for going to one? [by Ken Hunt, London] In 1955 North America’s modern-era fascination with Hindustani music began with the advent of jet travel and the arrival of the sarod maestro Ali Akbar Khan in New York. By then, Shamin Ahmed Khan, born in Baroda, Baroda State (modern-day Gujarat) on 10 September 1938, had already met the musician who would transform his life.

[by Ken Hunt, London] In 1955 North America’s modern-era fascination with Hindustani music began with the advent of jet travel and the arrival of the sarod maestro Ali Akbar Khan in New York. By then, Shamin Ahmed Khan, born in Baroda, Baroda State (modern-day Gujarat) on 10 September 1938, had already met the musician who would transform his life. As one of Shankar’s first shishyas, he ‘commuted’ the 1000 km between Baroda and his guru’s home. When he moved to Bombay in 1960, Shamim Ahmed relocated to fill a teaching position at Shankar’s Kinnara School of Music. In 1968 Shankar invited him to California to be one of the young lions on what became immortalized as Ravi Shankar’s Festival From India (World Pacific, 1968; BGO Records [reissue], 1996) – the sitar and sarod duet on rāg Kirwani with Ali Akbar Khan’s eldest son, Aashish Khan is one of the double-LP’s highlights.

As one of Shankar’s first shishyas, he ‘commuted’ the 1000 km between Baroda and his guru’s home. When he moved to Bombay in 1960, Shamim Ahmed relocated to fill a teaching position at Shankar’s Kinnara School of Music. In 1968 Shankar invited him to California to be one of the young lions on what became immortalized as Ravi Shankar’s Festival From India (World Pacific, 1968; BGO Records [reissue], 1996) – the sitar and sarod duet on rāg Kirwani with Ali Akbar Khan’s eldest son, Aashish Khan is one of the double-LP’s highlights. Shamim Ahmed Khan holds a special place in my heart. I took my young son Tom to one of his recitals, organised by the promoter Jay Viswa-Deva. Afterwards Shamim and I talked at length and he entreated me to pass my opinion of his performance to his guru. The recital was memorable for another reason. Tom and I fell into conversation with a charming woman. She was friendly and so attentive when it came to my lad. When I got home I related what had happened to my wife, Dagmar. The kind woman was the actress Vanessa Redgrave. Tom was aged under ten and had no idea who was talking to him so attentively.

Shamim Ahmed Khan holds a special place in my heart. I took my young son Tom to one of his recitals, organised by the promoter Jay Viswa-Deva. Afterwards Shamim and I talked at length and he entreated me to pass my opinion of his performance to his guru. The recital was memorable for another reason. Tom and I fell into conversation with a charming woman. She was friendly and so attentive when it came to my lad. When I got home I related what had happened to my wife, Dagmar. The kind woman was the actress Vanessa Redgrave. Tom was aged under ten and had no idea who was talking to him so attentively. [by Ken Hunt, London] At the time of the inspirational illustrator Maurice Sendak’s death, obituaries concentrated on his connections with Mozart, Prokofiev, Janáček and suchlike. On the occasion of the death of the US folksinger Jean Ritchie (1922-2015), it is time to remind about his bigger sound palette connections, notably one that coloured his early art. One commission revealed other musical tastes.

[by Ken Hunt, London] At the time of the inspirational illustrator Maurice Sendak’s death, obituaries concentrated on his connections with Mozart, Prokofiev, Janáček and suchlike. On the occasion of the death of the US folksinger Jean Ritchie (1922-2015), it is time to remind about his bigger sound palette connections, notably one that coloured his early art. One commission revealed other musical tastes. [by Ken Hunt, London] One of Europe’s foremost jazz critics, of a status comparable to Nat Henhoff in the States, died on 16 December 2013 in Prague. Lubomír Dorůžka rose to become the preeminent Czech-language jazz historian in Czechoslovakia and, after the separation in 1993, the Czech Republic. He was a Czech musicologist, music historian and critic (not just jazz), author, literary translator (including, naturally, the Jazz Age writings of F. Scott Fitzgerald and William Faulkner, amongst others) and much more. Lubo Dorůžka had the ill-starred fortune to be a jazz aficionado under two totalitarian regimes, during periods when to call jazz dangerous was an understatement.

[by Ken Hunt, London] One of Europe’s foremost jazz critics, of a status comparable to Nat Henhoff in the States, died on 16 December 2013 in Prague. Lubomír Dorůžka rose to become the preeminent Czech-language jazz historian in Czechoslovakia and, after the separation in 1993, the Czech Republic. He was a Czech musicologist, music historian and critic (not just jazz), author, literary translator (including, naturally, the Jazz Age writings of F. Scott Fitzgerald and William Faulkner, amongst others) and much more. Lubo Dorůžka had the ill-starred fortune to be a jazz aficionado under two totalitarian regimes, during periods when to call jazz dangerous was an understatement.