Lives

[by Ken Hunt, London] Bass player Chris Ethridge (top right in photograph), who died on 23 April 2012 in his birth town of Meridian, Mississippi was one of the sidemen whose curriculum vitae was lit with musical magic and yet overshadowed in some way by one of his early excursions into working as a musician, even though he played bass with Willie Nelson during in the 1970s and 1980s.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Bass player Chris Ethridge (top right in photograph), who died on 23 April 2012 in his birth town of Meridian, Mississippi was one of the sidemen whose curriculum vitae was lit with musical magic and yet overshadowed in some way by one of his early excursions into working as a musician, even though he played bass with Willie Nelson during in the 1970s and 1980s.

Born John Christopher Ethridge II on 10 February 1947, he first made an impression with the Flying Burrito Brothers on their remarkable debut LP, The Gilded Palace of Sin (1969) with his bass playing and song credits. This group also included Gram Parsons on guitar (top left in photograph) and lead vocals, Chris Hillman, one of the founding members of the Byrds, playing stringed instruments. The pedal steel (bottom right) and guitarist Pete Kleinow (bottom left) completed the pre-drummer line-up.

Holed up in the chic as shit San Fernando Valley in the Los Angeles metroplitan conurbation, they had set about creating a Flying Burrito Brothers repertoire of original songs and a good few covers – notably Dan Penn and Chips Moman’s Dark End of Street and Do Right Woman – for that debut LP. In concert and radio broadcasts though, they augmented Gilded Palace repertoire with songs such as Dream Baby (How Long Must I Dream), Sing Me Back Home, Close Up The Honky Tonks and You Win Again.

Ethridge’s previous band had also featured Gram Parsons. That band, the International Submarine Band made one album Safe At Home which also featured Ethridge, unlike earlier singles. It was released after the band’s break-up in 1968. By that time its leading light, Gram Parsons was over the hills and far away – and indeed working with the Byrds of the Sweetheart of the Rodeo-era. Parsons chose not to stick with the Byrds. By 1968 he was gone and founded the Burritos, still without a permanent drummer when they cut that superlative debut of years. In A&M house photographer, Jim McCrary’s imagery, they were captured wearing Nudie suits. Ethridge’s had rose motifs

Two of that album’s strongest songs – Hot Burrito #1 and Hot Burrito #2 – carried joint Ethridge/Parsons compositional credits. For them alone, Ethridge is worthy of being remembered. Hot Burrito #1 went on to grace Elvis Costello’s Nashville Bash Almost Blue (1981) under the title I’m Your Toy with John McFee adding pedal steel guitar to the track. Ethridge went on to co-pen She with Gram Parsons. One of Gram Parsons’ most memorable vehicles, arguably Hot Burrito #1, Hot Burrito #2 and She are Parsons’ three greatest originals. Etheridge did not play on Parsons’ solo debut GP (1973).

Two of that album’s strongest songs – Hot Burrito #1 and Hot Burrito #2 – carried joint Ethridge/Parsons compositional credits. For them alone, Ethridge is worthy of being remembered. Hot Burrito #1 went on to grace Elvis Costello’s Nashville Bash Almost Blue (1981) under the title I’m Your Toy with John McFee adding pedal steel guitar to the track. Ethridge went on to co-pen She with Gram Parsons. One of Gram Parsons’ most memorable vehicles, arguably Hot Burrito #1, Hot Burrito #2 and She are Parsons’ three greatest originals. Etheridge did not play on Parsons’ solo debut GP (1973).

Ethridge had vamoosed by the time the Burritos made their second album, Burrito Deluxe (1970). He entered into the world of sessions where his bass playing worked well by melting away the stylistic walls between country, rock’n’roll and R&B. Amongst the most memorable of his sessions were Judy Collins’ Who Knows Where The Time Goes (1968), Phil Ochs’ Greatest Hits (1970), Arlo Guthrie’s Washington County (1970), Rita Coolidge’s eponymous album (1973) and three of Ry Cooder’s early must-hears – Ry Cooder (1970), Paradise and Lunch (1974) and, best of all, Chicken Skin Music (1976). With Joel Scott Hill and John Barbata, Ethridge also recorded the jointly credited, rather identity-less and lacklustre L.A. Getaway (1970)

As a member of Willie Nelson’s touring band, he toured extensively as well as contributing to the Booker T. Jones-produced Stardust (1978). The album was a fine balancing act, for Nelson was not delivering what was necessarily expected of him with its covers of the Kurt Weill/Maxwell Anderson September Song, the Hoagy Carmichael/Stuart Gorrell Georgia On My Mind, the Jimmy McHugh/Dorothy Fields Sunny Side of the Street and the George Gershwin/Ira Gershwin Someone To Watch Over Me.

As a member of Willie Nelson’s touring band, he toured extensively as well as contributing to the Booker T. Jones-produced Stardust (1978). The album was a fine balancing act, for Nelson was not delivering what was necessarily expected of him with its covers of the Kurt Weill/Maxwell Anderson September Song, the Hoagy Carmichael/Stuart Gorrell Georgia On My Mind, the Jimmy McHugh/Dorothy Fields Sunny Side of the Street and the George Gershwin/Ira Gershwin Someone To Watch Over Me.

The copyright of all other images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers. With particular thanks to Michael Moser.

Jim McCrary’s obituary by Valerie J. Nelson from the Los Angeles Times dated 6 May 2012 is at http://www.latimes.com/news/obituaries/la-me-jim-mccrary-20120506,0,1555697.story

18. 5. 2012 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The mridangam virtuoso Palghat T.S. Mani Iyer, born 100 years ago in Palghat (the anglicised version of Palakkad) in Kerala, was one of the musical giants of the Twentieth Century. Prior to him, the mridangam had filled the subordinate time- and tempo-supporting role – the usual role of drums in both of the subcontinent’s art music systems and folk traditions. He was one of a generation of musicians that changed the complexion of South Indian music.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The mridangam virtuoso Palghat T.S. Mani Iyer, born 100 years ago in Palghat (the anglicised version of Palakkad) in Kerala, was one of the musical giants of the Twentieth Century. Prior to him, the mridangam had filled the subordinate time- and tempo-supporting role – the usual role of drums in both of the subcontinent’s art music systems and folk traditions. He was one of a generation of musicians that changed the complexion of South Indian music.

His vision and innovation was to shift the balance, so that, in his hands, the mridangam attained a greater melodic role with phrasing that reflected the words, whether sung or unsung. He redefined the artistry of the South’s principal barrel drum and rewrote the figurative book, inspiring such mridangists as Palghat R. Raghu (1928-2009) and Umayalpuram K. Sivaraman (b 1935) – and players he never met – to take his innovations and explore them further.

In 1940 Palghat R. Raghu’s family moved to Palghat, specifically so he could study drumming with Palghat Mani Iyer. Recalling this, he said, “Becoming his disciple was, for me, a dream come true,” In 1948 he wed Palghat T.S. Mani Iyer’s niece Swarnambal, further reinforcing the ties between guru and pupil. Mani Iyer guru had begun his career in music in 1924 at the age of twelve, accompanying the vocalist Chembai Vaidyanatha Bhagavatar (1896-1974) – Chembai being a village near Palghat – with whom he would work and grow over succeeding decades.

Mani Iyer was also part of the post-Second World War artistic explosion that brought South Asian classical music to Britain and elsewhere. He appeared at the pivotal 1965 Edinburgh Festival accompanying the Karnatic principal vocal soloist K.V. Narayanaswamy with his son Rajamani as second mridangist and the violinist Lalgudi G. Jayaraman.

Mani Iyer changed the face of mridangam playing. He reinforced the realisation that the rhythmist’s role could also be to colour and reflect the words as they unfolded.

Further reading

To learn more about Palghat Mani Iyer, the violinist daughter of Lalgudi G. Jayaraman, Lalgudi Vijayalakshmi’s article ‘A genius who redefined the art of mridangam playing’ from em>The Hindu of 28 December 2011 is recommended reading: http://www.thehindu.com/arts/music/article2755328.ece?homepage=true

Ken Hunt’s obituary of Palghat R. Raghu ‘Palghat R. Raghu: Master of Indian percussion who played with Ravi Shankar and Alla Rakha’ from The Independent of 30 June 2009 is at: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/palghat-r-raghu-master-of-indian-percussion-who-played-with-ravi-shankar-and-alla-rakha-1724491.html

The artwork for South Indian Strings: Presenting The Art of Dr. L. Subramaniam with Palghat T.S. Mani Iyer (Lyrichord Records LLST 7350, 1981) finds him seated on the viewer’s far left – image © Lyrichord.

23. 1. 2012 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Lovin’ Spoonful was a band that, in the most cool of manners, took its name from a Mississippi John Hurt recording. They made a music that brought together jug band (skiffle) music, folk and folk-blues with an added pop into rock sensibility around 1966 when nobody knew exactly what was going on and definitely nobody knew where it was all going to go.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Lovin’ Spoonful was a band that, in the most cool of manners, took its name from a Mississippi John Hurt recording. They made a music that brought together jug band (skiffle) music, folk and folk-blues with an added pop into rock sensibility around 1966 when nobody knew exactly what was going on and definitely nobody knew where it was all going to go.

Born in Toronto on 19 December 1944, Zalman ‘Zal’ or ‘Zally’ Yanovsky (bottom left on the album sleeve in yellow and orange stripes, next to John Sebastian’s orange and white stripes) died days short of his 57th birthday on 13 December 2002. Arriving on the Eastern seaboard of Canada’s southern neighbour with a trio called the Halifax Three – its Halifax, Nova Scotia-born Dennis Doherty subsequently went on to well for himself in The Mamas and The Papas – Yanovsky made contacts that in New York found him and Doherty joining the Mugwumps. That group was name-checked in the Mamas And The Papas’ potted history of folk into rock, Creeque Alley – a baton of an autobiographical history that the Grateful Dead’s Truckin’ took up and ran with.

“The Mugwumps didn’t make many records,” wrote Michelle Phillips in her autobiography, California Dreaming – The True Story of The Mamas And The Papas (1998), “but they became legendary after they had broken up. They were a cult after the event.” Keeping careful-with-the-‘legendary’-axe, St. Eugene (British Columbia) business the crowd’s comings and goings enabled them to be a backbone of a Pete Frame rock family tree.

Yanovsky joined the Lovin’ Spoonful and became intrinsic to its succession of local, then national, then international hits. Those hits included Do You Believe In Magic, Daydream and Summer In The City. Those songs were as other and distinctive as anything that the Rolling Stones, The Kinks or the Small Faces were releasing in Britain. They shone out.

Everything was going so well… Then in 1966 with Summer In The City roaring up the charts internationally, Yanovsky and Steve Boone found themselves in a bit of a quandary. They got busted in San Francisco for possession of marijuana – it was still illegal in California back then. (May still be.)

Pressure was applied. Fearful of visa problems, they sang. “The episode,” observed Joel Selvin in Summer of Love (1994), “finished the Spoonful in underground circles.” Back then even if we didn’t know the exact detail, there was enough scurrilous stuff flying around to glean that all was not right in the state of the Spoonful. Mud stuck.

Post-Spoonful Yanovsky played with Kris Kristofferson – I saw him at the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival – and he made a cameo appearance in Paul Simon’s One Trick Pony (1980). At the time of his death, he was a restaurateur in Kingston, Ontario in a place wittily called Chez Piggy.

For more information about Frame and his Rock Trees – visit http://blog.familyofrock.com/

10. 10. 2011 |

read more...

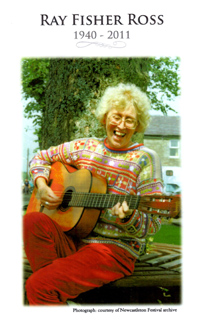

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Scottish folksinger Ray Fisher once told me that she had a series of scheduled performances in Czechoslovakia that were abruptly cancelled when the Soviet bloc forces had the bad manners to invade in 1968. The following year, rescheduled concerts finally took place. She recalled the mayor of one town greeting her. Two Soviet officers flanked him. The mood was tense. Then, one of them broke the ice by asking her excitedly whether she knew the Beatles. (With her winsome charm, no doubt she pulled it off effortlessly but alas I have no memory of how exactly she got out of that one.) As part of the cultural exchange, the tour introduced her to dudy – Czech bagpipes and ‘bagpipes’ in Czech – and she remembered the experience with wry fondness.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Scottish folksinger Ray Fisher once told me that she had a series of scheduled performances in Czechoslovakia that were abruptly cancelled when the Soviet bloc forces had the bad manners to invade in 1968. The following year, rescheduled concerts finally took place. She recalled the mayor of one town greeting her. Two Soviet officers flanked him. The mood was tense. Then, one of them broke the ice by asking her excitedly whether she knew the Beatles. (With her winsome charm, no doubt she pulled it off effortlessly but alas I have no memory of how exactly she got out of that one.) As part of the cultural exchange, the tour introduced her to dudy – Czech bagpipes and ‘bagpipes’ in Czech – and she remembered the experience with wry fondness.

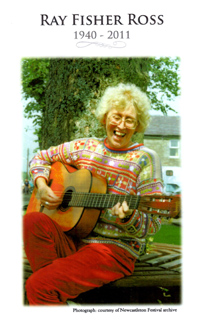

Born in Glasgow, Scotland on 26 November 1940, in 1962, she had married Colin Ross, the fiddler and piper, and later co-founder of the High Level Ranters, and settled in Tyneside. With her marriage to Colin, she was wed – or, as she sometimes joked – widowed to the pipes. She was one of six daughters – Jean, Joyce, Cindy, Audrey and Priscilla – and one token son – Archie – born into a family with catholic musical tastes that included light operatic and parlour fare (their father John Galbraith Fisher sang in the City of Glasgow police choir), Scots and, since their mother, Marion née MacDonald (known as Morag or Ma Fisher) had it as her mother tongue, Gaelic songs. Like many folkies of her generation, Britain’s skiffle movement was the springboard to a greater awareness of folk music. Through a fluke of fate and proximity, a bloke who owned a local record shop lent US import LPs on Folkways by Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, Buell Kazee and Aunt Samantha Bumgarner to Hamish Imlach, whose Cod Liver Oil and The Orange Juice – Reminiscences of a Fat Folk Singer – discusses the early Glasgow folk scene. Imlach borrowed them because he was the one with a record player that could play them.

Born in Glasgow, Scotland on 26 November 1940, in 1962, she had married Colin Ross, the fiddler and piper, and later co-founder of the High Level Ranters, and settled in Tyneside. With her marriage to Colin, she was wed – or, as she sometimes joked – widowed to the pipes. She was one of six daughters – Jean, Joyce, Cindy, Audrey and Priscilla – and one token son – Archie – born into a family with catholic musical tastes that included light operatic and parlour fare (their father John Galbraith Fisher sang in the City of Glasgow police choir), Scots and, since their mother, Marion née MacDonald (known as Morag or Ma Fisher) had it as her mother tongue, Gaelic songs. Like many folkies of her generation, Britain’s skiffle movement was the springboard to a greater awareness of folk music. Through a fluke of fate and proximity, a bloke who owned a local record shop lent US import LPs on Folkways by Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, Buell Kazee and Aunt Samantha Bumgarner to Hamish Imlach, whose Cod Liver Oil and The Orange Juice – Reminiscences of a Fat Folk Singer – discusses the early Glasgow folk scene. Imlach borrowed them because he was the one with a record player that could play them.

Recorded music, like these Folkways LPs and the Weavers, fed the heads of Archie, Bobby Campbell and Ray informing their skiffle group’s repertoire. “It was really through Archie,” she told Howard Glasser in an interview for Sing Out! in 1974 (Volume 22/number 6), “that I first started singing. Archie and I and Bobby Campbell went to the same school. Bobby played violin in the school orchestra. At the time in Glasgow there were lots of skiffle groups, and Archie and Bobby decided they were going to start a group.” The Wayfarers would open for Pete Seeger in Glasgow, Edinburgh and Aberdeen. And that was no small deal.

Ray also studied with the Scottish Traveller ballad singer, Jeannie Robertson, spending her school summer holidays in her finals year and learning from her . It was an extraordinarily brave thing to do. It flew in the face of convention since many viewed Travellers with suspicion. By staying at Robertson’s home in Aberdeen, she dismissed prejudices and warinesses about the Traveller community. Over those six weeks, she imbibed open-mindedly. When she left, she understood. It was one of the experiences that turned her into one of Scotland’s finest interpreters of folk material. She heard Jeannie Robertson, later, in 1968, to be appointed MBE for her services to traditional music, sing not only the big ballads but also the radio hits of the day whilst doing the washing up. Ray Fisher never unlearned those lessons.

Ray and Archie Fisher formed a duo which lasted until 1962 when she moved to Tyneside. Archie recalled at Ray’s funeral that living in two different cities meant that they had little chance to rehearse for their appearances. Rehearsing was quite important as the duo was appearing on the Scottish television teatime magazine programme, Here And Now. Actually, very important, as they were going out live. Since his financial position was weaker, he would reverse the charges (call collect for North American readers) and they would rehearse for their broadcasts over the phone. Camouflaging the extent of their under-rehearsal on screen they would look directly into each other’s eyes. This look is captured well in one famous image from Brian Shuel’s portfolio of photographs. One important reason for looking so intently at each other is that they were lip-reading as well in order to get the lyrics right. The duo’s EP Far Over The Forth EP (Topic, 1961) captures the period and the folkier side of their repertoire well but in the television studio they were also running through an output of topical songs in the style of the day, many of which were learnt for the transmission and then forgotten. Far Over The Forth Scots had an unabashed Scottish focus and regionality, something that would take on a greater significance in future years. Both Dick Gaughan and Anne Briggs took direction from it.

Singing for Labour Party events, Centre 42 concert parties, pro-CND, anti-Polaris protests and Aldermaston marches brought Ray further into left-wing political circles. In the period between 1963 and 1965, she contributed to three important projects and a handful of ‘various artists’ projects, notably the fake Edinburgh Folk Festival anthologies (actually recorded specifically for Decca in a studio ‘re-creation’ of the festival experience). The first was A.L. Lloyd’s The Iron Muse. This was, Bert Lloyd explained in the LP notes, an album of industrial songs. “‘What is folk song?’ he asked as his opening rhetorical flourish. “The term is vague and seems to be getting vaguer. However, the songs on this record may conveniently be called ‘industrial folk songs’ for without exception they were created by industrial workers out of their own daily experience and were circulated, mainly by word of mouth, to be used by the songmakers’ workmates in mines, mills and foundries.” Both Ray and her husband Colin contributed to this project, as they did to the sixth On The Edge radio ballad, a form of audio-documentary with song, devised and developed by Ewan MacColl, Charles Parker and Peggy Seeger for BBC radio. First broadcast in February 1963, it addressed the transition from childhood to adolescence to adulthood. (First released on LP on the Argo label in 1967, it was reissued as a Topic CD (Topic TSCD 806) in 1999 as part of Topic’s radio ballad release programme.)

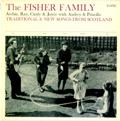

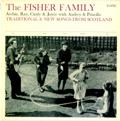

Most important of all, many would consider, was Topic’s LP The Fisher Family, recorded in 1965 and released the following year. Its subtitle said ‘Traditional and New Songs from Scotland’. Bill Leader recorded it at the Fisher Family palace, while Joe Boyd, his assistant on the job (later to achieve other things through Witchseason, Island, Elektra, Reprise and more, but also the snapper that captured the cover image), slept in the car outside because there was no more room in the palace. At her funeral, her surviving sisters sang Ewan MacColl’s Come All Ye Fisher Lasses, the album’s opening track on which Ray had sung lead.

Most important of all, many would consider, was Topic’s LP The Fisher Family, recorded in 1965 and released the following year. Its subtitle said ‘Traditional and New Songs from Scotland’. Bill Leader recorded it at the Fisher Family palace, while Joe Boyd, his assistant on the job (later to achieve other things through Witchseason, Island, Elektra, Reprise and more, but also the snapper that captured the cover image), slept in the car outside because there was no more room in the palace. At her funeral, her surviving sisters sang Ewan MacColl’s Come All Ye Fisher Lasses, the album’s opening track on which Ray had sung lead.

A short digression. The tail end of Cyclone Katia was still blowing the day of the funeral – 12 September 2011 – and trains down to London were delayed more than somewhat by fallen trees. When we reached London, a disparate band of stranded travellers arrived to missed connections and last trains gone. The rail company laid on taxis and bundled people with nearby destinations off together. Finding common cause in adversity, we chatted and a Scottish woman talked about missing her friend’s wedding because of rail staff misdirecting on to a train, the first stop turned out to be the wrong side of the border, Newcastle upon Tyne. She spoke of crying uncontrollably and MacColl’s words “greet like a wean” (‘weep like a child’) from Come All Ye Fisher Lasses came back to me. After hearing them an English voice use those words, she repeated them in half-surprise and burst into laughter.

Ray expressed little interest in recording, being averse to the regime of recording studios and much preferring the spontaneity of singing to living, breathing humans or delivering something live, say, to radio. Never partial to the studio recording process, she successfully managed to manoeuvre in the most eel-like of ways and succeeded in putting off recording her debut solo debut, The Bonny Birdie (Trailer, 1972) into the next decade. This was a feat in itself. Again recorded by Bill Leader (with Seumas Ewens assisting), its producer Ashley Hutchings brought in a bunch of musicians to re-upholster the arrangements with Martin Carthy, Tim Hart and Peter Knight and Hutchings himself from the Steeleye Span circle, Alistair Anderson and Colin Ross by then members of the High Level Ranters, Bobby Campbell (long past his Wayfarers days) and Liz and Stefan Sobell. Typical of her dry wit, she explained of The Forfar Sodger (The Forfar Soldier) that, “To hirple means to hobble (as if you didn’t know!)” The album was later reissued by Highway Records and still later fell foul of the contractual conundrums presented by the demise of Bill Leader’s Leader and Trailer labels. Ten years later she made her second album Willie’s Lady (Folk-Legacy, 1982). Less florid, more natural than The Bonny Birdie, it felt closer to her live act – not that records any longer needed to be mere reflections of concert performance or a folk club repertoire. Its magnificent title track, a slow build-up of accumulated repetitions from a pre-televisual age, appeared six years after Martin Carthy’s version on Crown of Horn (Topic, 1976). In fact, they had cracked their individual versions – hers in Scots, his in English – the same night when Carthy stayed with the Rosses in Monkseaton. Another highlight was the closing track, her treatment of Alan Rogerson’s version of When Fortune Turns The Wheel – a song she had learned from Lou Killen. Between those two songs you discover what made her unique as a singer and song interpreter.

In 1991 she released her third and final solo album Traditional Songs of Scotland which complemented Saydisc’s English and Welsh companion volumes – Jo Freya’s Traditional Songs of England and Siwsann George’s Traditional Songs of Wales/Caneuon Traddodiadol Cymru. Its out-take Now Westlin’ Winds, with Martin Carthy accompanying on guitar, from the same sessions appeared on the seasonal round anthology, All Through The Year (Fledg’ling, 1991).

In 1991 she released her third and final solo album Traditional Songs of Scotland which complemented Saydisc’s English and Welsh companion volumes – Jo Freya’s Traditional Songs of England and Siwsann George’s Traditional Songs of Wales/Caneuon Traddodiadol Cymru. Its out-take Now Westlin’ Winds, with Martin Carthy accompanying on guitar, from the same sessions appeared on the seasonal round anthology, All Through The Year (Fledg’ling, 1991).

Long associated with the Newcastle upon Tyne folk scene, whether ‘knitting’ bags for her pipe-maker husband’s much sought-after Northumbrian pipes or just singing or adding drolleries of the spoken monologue or parody song type, she appeared on 50 Years of Folk Music in Newcastle (Ceilidh Connections, 2009) performing her arch monologue Behave Yoursel’ – a treatise on declining standards in public places – and, accompanied by Tom Gilfellon on guitar, Generations of Change and Old Maid In A Garret. It was a no-frills double-CD celebrating a half-century of one of Britain’s finest folk hubs – the club that began as Folksong and Ballad before becoming the Bridge Folk Club and most especially known from its time at the Barras Bridge Hotel in the city. It ranked, I wrote in R2, as “one of the folk scene’s very most important outposts when the likes of Mike Waterson … willingly thumbed it from Hull to Liverpool (pre-motorway system) in order to visit the Spinners’ folk club.” I continued, “You get the club’s founding fathers – Johnny Handle and Louis Killen – in the glad company of past and present High Level Ranters (surely verging on the holotypic in a folk revival band sense and absolutely one of Britain’s finest), Chris Hendry, Ray Fisher, Pete Wood, John Brennan and others. … 50 Years of Folk Music in Newcastle brilliantly distils the essence of not merely one but this country’s whole folk club movement.”

Long associated with the Newcastle upon Tyne folk scene, whether ‘knitting’ bags for her pipe-maker husband’s much sought-after Northumbrian pipes or just singing or adding drolleries of the spoken monologue or parody song type, she appeared on 50 Years of Folk Music in Newcastle (Ceilidh Connections, 2009) performing her arch monologue Behave Yoursel’ – a treatise on declining standards in public places – and, accompanied by Tom Gilfellon on guitar, Generations of Change and Old Maid In A Garret. It was a no-frills double-CD celebrating a half-century of one of Britain’s finest folk hubs – the club that began as Folksong and Ballad before becoming the Bridge Folk Club and most especially known from its time at the Barras Bridge Hotel in the city. It ranked, I wrote in R2, as “one of the folk scene’s very most important outposts when the likes of Mike Waterson … willingly thumbed it from Hull to Liverpool (pre-motorway system) in order to visit the Spinners’ folk club.” I continued, “You get the club’s founding fathers – Johnny Handle and Louis Killen – in the glad company of past and present High Level Ranters (surely verging on the holotypic in a folk revival band sense and absolutely one of Britain’s finest), Chris Hendry, Ray Fisher, Pete Wood, John Brennan and others. … 50 Years of Folk Music in Newcastle brilliantly distils the essence of not merely one but this country’s whole folk club movement.”

Folk clubs were Ray’s driving force when it came to making music. She loved the folk club scene. She stoutly avoided recording under her own name. In an interview with me, published in Swing 51Crab Wars she and a front row of nasty people hid crab shells under their chairs. At the critical moment, the concealed crab carapace percussion was whipped out and clattered in an attempt to get the Kippers to corpse.

PS At Ray’s funeral in Whitley Bay there was much piping and singing. At one point Martyn Wyndham-Reed movingly sang The Rose, a Greenwich Village single of his on which Ray had sung in 1984 – the same song that Bette Midler had sung. Adding the backing vocals were Cilla Fisher, Di Henderson (on whose By Any Other Name (DH, 1991) Ray had also sung) and Cilla’s daughter Jane.

Jane sings with the Glasgow-based electro, punk and rock’n’roll band Fangs. Wonderful to discover that yet another generation of Fishers is singing. For more information and to try This Is Art for starters, visit http://www.myspace.com/fangsfangsfangs

The main image is © Sandy Paton/Folk-Legacy Records, cropped from the album sleeve of Willie’s Lady, the yesty image of Ray from her funeral programme is courtesy of the Newcastleton Festival archive, photographer unknown. The copyright of all other images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers.

With thanks to Cilla Fisher.

19. 9. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] To be truthful, there really have been very few disc jockeys who have changed society’s attitudes to music. Tom Donahue introduced a virus to North American radio programming. Donahue’s infected the San Francisco Bay Area. By circumventing conventional playlist conventions, he wove an unconventional tapestry that enabled listeners to think beyond the commercially regulated 45 rpm format, think about LP-length tracks as a format and thus to think for themselves. The pendulum had swung slow for too long and it needed adjusting because it was no longer in time with the times. John Peel did that too, only he took things further and took his catholic tastes and musical worldview to places far beyond an English recording studio.

[by Ken Hunt, London] To be truthful, there really have been very few disc jockeys who have changed society’s attitudes to music. Tom Donahue introduced a virus to North American radio programming. Donahue’s infected the San Francisco Bay Area. By circumventing conventional playlist conventions, he wove an unconventional tapestry that enabled listeners to think beyond the commercially regulated 45 rpm format, think about LP-length tracks as a format and thus to think for themselves. The pendulum had swung slow for too long and it needed adjusting because it was no longer in time with the times. John Peel did that too, only he took things further and took his catholic tastes and musical worldview to places far beyond an English recording studio.

Maybe it took those with an open-minded, Rabelaisian streak to break the mould. John Peel had that streak but what he also possessed was a complete lack of ambition for turntable work as a springboard to hosting quiz shows on daytime television. He was, simply put, the most important, if not the most influential, broadcaster in the UK. That said, through his broadcasts on the BBC World Service and variously named British Forces radio stations, he reached out to a global audience making one of the world’s most important opinion-formers ever in music. It wasn’t all epiphany. He wasn’t selling epiphanies. Sure he shaped opinions but basically he gave people the chance to make their own minds up.

He was renowned for playing what he liked and generally liking and championing what he played (though sometimes he just played music that piqued his curiosity because he knew he was undecided enough about it to give it the benefit of the doubt). Arguably, he was the most important music broadcaster of his time in the world. If that curdles anyone’s milk, name the pretender to that throne.

He was renowned for playing what he liked and generally liking and championing what he played (though sometimes he just played music that piqued his curiosity because he knew he was undecided enough about it to give it the benefit of the doubt). Arguably, he was the most important music broadcaster of his time in the world. If that curdles anyone’s milk, name the pretender to that throne.

Born John Robert Parker Ravenscroft on 30 August 1939 in the Wirral in Heswall, Cheshire, he admitted that two records changed his life. One was Heartbreak Hotel; the other Rock Island Line. Peel borrowed his nom de wireless from a popular folksong. He talked about adventures out in the States during Beatlemania (and how he became an instant Beatle specialist with accent and instant exploitative ‘Liverpudlian’). Back in Britain, his attentions in his Radio London pirate radio days focussed on Country Joe & The Fish, Jimi Hendrix, the Incredible String Band, Pink Floyd, Forest, Principal Edward’s Magic Theatre, Tyrannosaurus Rex, Liverpool Scene and their kind.

He went on to BBC Radio One ushering in a period and patronage of acts such as the Undertones, Frank Chickens, Henry Cow, Oasis, Blur and worse. Droll, open and witty to an extreme, he gave exposure to generations of culturally significant music, without fear or (much) favour. His producer, John Walters once archly observed, “If Peely ever reaches puberty, we’re all in trouble.” He never sprouted musical pubes, thank heavens. He did, however, speak frankly about the consequences of carefree promiscuity in the pre-AIDS years. He remains a hero.

He went on to BBC Radio One ushering in a period and patronage of acts such as the Undertones, Frank Chickens, Henry Cow, Oasis, Blur and worse. Droll, open and witty to an extreme, he gave exposure to generations of culturally significant music, without fear or (much) favour. His producer, John Walters once archly observed, “If Peely ever reaches puberty, we’re all in trouble.” He never sprouted musical pubes, thank heavens. He did, however, speak frankly about the consequences of carefree promiscuity in the pre-AIDS years. He remains a hero.

He died on a working holiday in Cuzco, Peru on 25 October 2004.

Check out the books John Peel: Margrave of the Marshes and Ken Garner’s The Peel Sessions: A Story of Teenage Dreams and One Man’s Love of New Music but most of all those Peel Sessions (such as June Tabor’s above).

29. 8. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Patrick Galvin’s death on 10 May 2011 in his birth city of Cork received some attention, the way that Ireland’s foremost poets and men-of-letters get written up. Born on 15 August 1927, his obituaries raised the response of ‘Oh no, that will not do.’ Galvin was more than a poet and dramatist in the way he chronicled and portrayed his homeland, its history and its people. He had a parallel life as a singer and writer of Irish songs. His recording career began at Topic – Britain’s and the world’s oldest independent record label – in the early 1950s. He contributed a number of 78 rpm singles with Al Jeffrey, an early largely unsung hero of the post-war Folk Revival, accompanying him. Amongst them, were songs now largely seen as, or deemed standard repertoire through, say, the Dubliners, Thin Lizzy and Sinéad O’Connor.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Patrick Galvin’s death on 10 May 2011 in his birth city of Cork received some attention, the way that Ireland’s foremost poets and men-of-letters get written up. Born on 15 August 1927, his obituaries raised the response of ‘Oh no, that will not do.’ Galvin was more than a poet and dramatist in the way he chronicled and portrayed his homeland, its history and its people. He had a parallel life as a singer and writer of Irish songs. His recording career began at Topic – Britain’s and the world’s oldest independent record label – in the early 1950s. He contributed a number of 78 rpm singles with Al Jeffrey, an early largely unsung hero of the post-war Folk Revival, accompanying him. Amongst them, were songs now largely seen as, or deemed standard repertoire through, say, the Dubliners, Thin Lizzy and Sinéad O’Connor.

On disc he broke ‘new’ ground at times when anti-Irish bigotry stymied the commercial release of such material. Galvin’s first Topic single was Bonny Boy backed with She Moved Through the Fair, followed by Brown Girl and My Love Came to Dublin, Wild Colonial Boy and Football Crazy, Wackfoldediddle and Johnson’s Motor Car and The Women are Worse Than the Men and Whiskey In The Jar.

This was powerful voodoo galvanising poet Padraic Colum’s supernaturalism, football madness from another, perhaps less sectarian age and full-tilt, proselytising Irish rebel songs. This was leavened, however, by his abiding beliefs in socialism and the brotherhood of man. Topic also released long-players with Irish Songs of Resistance – exactly what was rattled in the tins – in their titles. His records were released in the USA on Stinson and Riverside.

He worked, reworked or tweaked song fare. That might be for The Boys of Kilmichael on Jimmy Crowley’s Uncorked (1998) or, probably his most widespread song, James Connolly, recorded on The Black Family (1986) and by Christy Moore who first recorded it on Prosperous (1972). John Spillane set Galvin’s The Mad Woman of Cork to music for his Hey Dreamer. In this pool, an image rises. Moore said he had learned James Connolly “many years ago from Dominic Behan” making it part of a cycle, just as Patrick Galvin would have wished. Galvin thus represents a link between the Irish folksong tradition, Seán Ó Riada, Dominic Behan and another century’s flowering of Irish song. And poeticism of a wider sort too, of course. In his One Voice – My Life In Song (2000), Moore wrote in the specific context of James Connolly, “While these songs are in performance they belong in the air. No one cares who wrote them while I sing them, they belong to us collectively.”

Further biographical reading: Patrick Galvin’s memoirs Raggy Boy (New Island Books, 2002)

Further information: http://www.informatik.uni-hamburg.de/~zierke/folk/records/patrickgalvin.html and Ralph Riegel’s obituary from Eire’s Sunday Independent of 15 May 2011 http://www.independent.ie/obituaries/patrick-galvin-2647558.html

17. 7. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The outstanding, trail-blazing Hindustani violinist Vishnu Govind Jog, usually known more simply as V.G. Jog, died in Kolkata (Calcutta) on 31 January 2004. He had been born in Bombay (now Mumbai), then in the Bombay Presidency (nowadays Maharashtra) in 1922. He received his early music training from several notables, amongst them, S.C. Athavaic, Ganpat Rao Purohit and Dr. S.N. Ratanjarkar, but where he differed from most of his contemporaries was his espousal and championing of the violin played in Indian tuning. To the north of the subcontinent, the European violin had little status. Professor V.G. Jog was a major force in correcting violinistic misperceptions. In Hindustani music the violin had (and has) to compete with the sarangi, an instrument of rare subtlety, capable of splitting the microtonal atom, as it were.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The outstanding, trail-blazing Hindustani violinist Vishnu Govind Jog, usually known more simply as V.G. Jog, died in Kolkata (Calcutta) on 31 January 2004. He had been born in Bombay (now Mumbai), then in the Bombay Presidency (nowadays Maharashtra) in 1922. He received his early music training from several notables, amongst them, S.C. Athavaic, Ganpat Rao Purohit and Dr. S.N. Ratanjarkar, but where he differed from most of his contemporaries was his espousal and championing of the violin played in Indian tuning. To the north of the subcontinent, the European violin had little status. Professor V.G. Jog was a major force in correcting violinistic misperceptions. In Hindustani music the violin had (and has) to compete with the sarangi, an instrument of rare subtlety, capable of splitting the microtonal atom, as it were.

In 1938 he met the multi-instrumentalist Allauddin Khan in Lucknow who became his guru, as he was to, amongst others, his son Ali Akbar Khan, his daughter Annapurna Devi, his eventual son-in-law Ravi Shankar and the sarodist Sharan Rani. In 1982 the violinist Jog was awarded India’s highest honour in the field, the Padma Bhushan, the nation’s third highest civilian award. By then he had changed people’s perception of the instrument in the Hindustani realm.

To give a few entry points, try his out-of-print jugalbandi (duet) with the shehnai (shawm) maestro Bismillah Khan for EMI’s ‘Music From India Series’. More readily available are his duets with the guitarist Brijbhushan Kabra for the German Chhanda Dhara label (1988) and the santoor player Tarun Bhattacharya for Nataraj Music (1993). In a solo sphere, his renditions of his namesake raga – Jog – for Moment (1991), his 1981 recording of Kirwani and Kajri for Navras (1996) or his All India Radio-derived recordings in T Seroes’ Immortal Series are good entry points. Anybody interested in the violin’s potential should listen to him. One of the great, great masters.

To give a few entry points, try his out-of-print jugalbandi (duet) with the shehnai (shawm) maestro Bismillah Khan for EMI’s ‘Music From India Series’. More readily available are his duets with the guitarist Brijbhushan Kabra for the German Chhanda Dhara label (1988) and the santoor player Tarun Bhattacharya for Nataraj Music (1993). In a solo sphere, his renditions of his namesake raga – Jog – for Moment (1991), his 1981 recording of Kirwani and Kajri for Navras (1996) or his All India Radio-derived recordings in T Seroes’ Immortal Series are good entry points. Anybody interested in the violin’s potential should listen to him. One of the great, great masters.

11. 7. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, Berlin] On 30 December 2003, Tanzania’s internationally best-known musician, Hukwe Zawose died at home in Bagamoyo, his musical base for many decades, at the age of 65. Tanzanian music never had much of an international profile outside of ethnography until Hukwe Zawose but when it arrived it arrived in style.

[by Ken Hunt, Berlin] On 30 December 2003, Tanzania’s internationally best-known musician, Hukwe Zawose died at home in Bagamoyo, his musical base for many decades, at the age of 65. Tanzanian music never had much of an international profile outside of ethnography until Hukwe Zawose but when it arrived it arrived in style.

Born in 1938 in Doduma, a rural district in central Tanganyika, as it was then known, he had an active recording career outside his homeland, recording for Real World, the Tokyo-based Seven Seas/King Record Co, Triple Earth (the London-based label that brokered and oversaw his international breakthrough) and WOMAD Select (notably the Mkuki Wa Rocho (A Spear To The Soul) album, 2002). Even if most people never bothered to learn about Wagogo as opposed to Tanzanian culture, Zawose became the one name that people remembered when it came to Tanzania’s folkways or, cynically mumbled, its ‘World Music’.

Born in 1938 in Doduma, a rural district in central Tanganyika, as it was then known, he had an active recording career outside his homeland, recording for Real World, the Tokyo-based Seven Seas/King Record Co, Triple Earth (the London-based label that brokered and oversaw his international breakthrough) and WOMAD Select (notably the Mkuki Wa Rocho (A Spear To The Soul) album, 2002). Even if most people never bothered to learn about Wagogo as opposed to Tanzanian culture, Zawose became the one name that people remembered when it came to Tanzania’s folkways or, cynically mumbled, its ‘World Music’.

In 1961 the British granted Zawose’s homeland independence. In the spirit of President Julius Nyerere’s socialist-inspired Arusha Declaration of 1967, the nation extolled self-reliance and social equality. As a by-product of nurturing national and rural resources, as opposed to rubber-stamping international exploitation, Tanzanian culture thrived. Zawose was of an age and was sufficiently rooted in his home-culture for him to find a niche as a musician in the new state. His father had steeped him in the Wagogo people’s traditional folkways and had given him a grounding in several traditional instruments. These included the iseze family of stringed instruments encountered in a variety of strung and sized forms, and marimba and its diminutive form known as chirimba, a metal-tongued instrument plucked with the thumbs, hence the generic English-language name ‘thumb piano’. (Elsewhere in Africa the instrument is known variously as sanza, mbira, kalimba and so on.) Zawose also developed into a singer of gifted sensitivity with a vocal range that went from a natural speaking range to a throaty falsetto.

Tanzania’s economy affected domestic commercial recording activities. There was no real recording industry in any ‘developed nation’ sense. What was released was typical cassette fare. Iain Scott remembers that Zawose was first recorded privately by Tanzania’s future Minister for Sport and Culture, Godwin Z. Kaduma (though he only ever heard about these recordings by repute). As happened in the Eastern European bloc, Tanzania had nurtured folkloristic ensembles as expressions and emblems of pan-Tanzanian culture. These performed an acceptable brand of people’s art, often mixing and matching traditions and straddling the linguistic and cultural divides in the creation of a national sensibility (and unity). It was in two such ensembles that Zawose made his first impressions on the international consciousness. These were the Bagamoyo College of Arts – a pan-Tanzanian cultural troupe – and the Tanzanian National Dance Troupe – a typical socialist state, folkloristic ensemble.

What turned Zawose’s life around was his appearance at the 1984 Commonwealth Institute’s ‘Africa, Africa’ programme in London because Iain Scott was so moved by the Bagamoyo College of Arts that he arranged for them to go into a studio. They were recorded on an 8-track, one-inch machine. The sessions resulted in Tanzania Yetu (Our Tanzania) (1985), one of the greatest East African albums ever. It became the inaugural release on Scott’s visionary Triple Earth label, giving him the confidence to record his likewise inspired work with Najma Akhtar and Aster Awake. It was, as I have written elsewhere, the first step in Zawose’s colonisation of the non-African mind. Ultimately everything streamed from those Chiswick, West London sessions.

Zawose went from strength to strength, working round the world at festivals, for example, WOMAD’s Mersea Island festival in 1985, and recording. Triple Earth’s Mateso (1987), an album (bolstered on CD by some tracks from Tanzania Yetu), received strong airplay in Britain, although back then, as now, that was a tiny proportion of airtime. In Scott’s opinion, its fortunes were turned about by Charlie Gillett and Andy Kershaw playing tracks from it. Unfortunately, Tanzania Yetu has never received a CD reissue in its entirety – nothing added, just left alone – that it deserved.

Zawose contributed to Music of Tanzania (1987), one of the Tokyo-based Seven Seas/King Record Co’s extensive World Music Library volumes. Zawose worked hard and over the following years, he consolidated and built his reputation. After his breakthrough work with Triple Earth, he fell into the Real World orbit. He recorded Chibite (1995) and Assembly (2002), a collaboration with Canada’s Michael Brook. In 2002 his nephew Charles Zawose and he supported Peter Gabriel on his ‘Growing Up Tour’ and their collaborative composition Animal Nation appeared in the soundtrack to animated The Wild Thornberrys Movie (2002).

27. 6. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Cast your mind back to 1971 and the film Caravan. That ever-risqué delight Helen is commanding the screen. A slinky saxophone croons over an electric bass guitar line with vibraphone in underlying support. Within a minute electric piano, trumpet and a splash of drums comes on the way eggs and flour get folded in gently when making a pudding. A spy flick tune emerges and then dissolves away. Helen pleads, “Lover, come to me now.” We are listening to Piya Tu Ab To Aaaja (‘Lover, Come to Me Now’, first line as title) with Asha Bhosle putting the words on Helen’s lips – with occasional cries of “Mon-i-kkka!” from the song’s composer Rahul Dev ‘Pancham’ Burman.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Cast your mind back to 1971 and the film Caravan. That ever-risqué delight Helen is commanding the screen. A slinky saxophone croons over an electric bass guitar line with vibraphone in underlying support. Within a minute electric piano, trumpet and a splash of drums comes on the way eggs and flour get folded in gently when making a pudding. A spy flick tune emerges and then dissolves away. Helen pleads, “Lover, come to me now.” We are listening to Piya Tu Ab To Aaaja (‘Lover, Come to Me Now’, first line as title) with Asha Bhosle putting the words on Helen’s lips – with occasional cries of “Mon-i-kkka!” from the song’s composer Rahul Dev ‘Pancham’ Burman.

This is not only the demi-monde of the Indian film Cabaret Song: this is the world of Manohari Singh – multi-instrumentalist, session musician, arranger, composer and shaper to the Bombay film industry. His saxophone plays such a small yet vital role in building the song’s sultry sexy charge, the embodiment of less being more. As an example of musical restraint, it has few peers in popular music. No wonder that Manohari Singh was such a massively important facilitator of R.D. Burman’s visions.

Born in Calcutta on 8 March 1931, Manohari Singh’s father had also played saxophone with the Calcutta police marching band. Like his father before him, Singh junior took up the ‘key flute’ (to differentiate it from the bansuri or bamboo flute) and saxophone. And because he played saxophone, he played clarinet because the two went together and saxophonists were expected to double up. The epitome of versatility, he performed with the Calcutta Symphony Orchestra and in jazz combos before moving, at music director Salil Chowdhury’s suggestion, to Bombay in 1958. The Bombay film industry was yet to gain its Bollywood sobriquet but whether you were a Bengali musician or a Punjabi music director (composer) and so on, you knew which side of the roti the ghee was buttered and where to gravitate in order to make some rupees and a reputation.

In Bombay he fell in with music director S.D. Burman’s son, Pancham. Eight years Singh’s junior, they would work together until Burman’s death on 4 January 1994 and co-create a phenomenal body of work, with many of Bollywood’s best-loved songs to their credit. Their ‘final’ collaboration was on Burman’s posthumous smash hit, 1942: A Love Story (1994). Whether he appeared as an anonymous session musician or under permutations of his name like Manohri Singh or Manhori, he was a musician of choice if saxophone or keyed flute were called for.

In Bombay he fell in with music director S.D. Burman’s son, Pancham. Eight years Singh’s junior, they would work together until Burman’s death on 4 January 1994 and co-create a phenomenal body of work, with many of Bollywood’s best-loved songs to their credit. Their ‘final’ collaboration was on Burman’s posthumous smash hit, 1942: A Love Story (1994). Whether he appeared as an anonymous session musician or under permutations of his name like Manohri Singh or Manhori, he was a musician of choice if saxophone or keyed flute were called for.

Parallel with his session work, Singh developed a public face, releasing albums under his own name. He brought the gift of being able to sight-read and being able to transpose into another key without having to write the notes out again to fit the new key. It is something, for instance, that Albert-system clarinettists learned to do intuitively when sight-reading clarinet music done by a Böhm/Boehm-system clarinettist. Following his death, Asha Bhosle told me, “Asha Bhosle explained: “Manohari could play a song in a different key without rewriting the notation. He knew every music part of thousands of songs by heart.”

Parallel with his session work, Singh developed a public face, releasing albums under his own name. He brought the gift of being able to sight-read and being able to transpose into another key without having to write the notes out again to fit the new key. It is something, for instance, that Albert-system clarinettists learned to do intuitively when sight-reading clarinet music done by a Böhm/Boehm-system clarinettist. Following his death, Asha Bhosle told me, “Asha Bhosle explained: “Manohari could play a song in a different key without rewriting the notation. He knew every music part of thousands of songs by heart.”

He died in Mumbai on 13 July 2010

Ken Hunt’s obituary of Manohari Singh from The Independent of 23 September 2010 is at: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/manohari-singh-saxophonist-who-made-his-instrument-central-to-bollywood-scores-2085593.html

23. 5. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The songwriter and singer Tim Rose died aged a day over 62, on 24 September 2002 in London just before a string of concerts.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The songwriter and singer Tim Rose died aged a day over 62, on 24 September 2002 in London just before a string of concerts.

Rose was born Timothy Alan Patrick Rose in Washington on 23 September 1940 and fetched up in Chicago where he became the sort of chap that might figure in one of Pete Frame’s family trees through his involvement in a folk group called the Triumvirate. They subsequently changed their name to the Big Three, a group that included Cass Elliott who went on to fame with the Mamas and the Papas.

In Greenwich Village he came to wider attention, playing the Bitter End and the Night Owl, before landing a contract with Columbia. Rose’s eponymous 1967 debut remains a classic of its kind. He would continue to release albums, albeit sporadically, until 1997, though after his death more emerged.

With a certain twist of fate however, it would be for two covers that he is best remembered. Namely, Hey Joe (a song also picked up on by Love and Jimi Hendrix) and Morning Dew (an underhand hijacking of Bonnie Dobson’s song that went into the repertoires of , amongst others, the Grateful Dead, Jeff Beck, Lulu, Einstürzende Neubauten, Ralph McTell and Robert Plant). Fatefully, Them and Judy Collins’ cover of Come Away, Melinda, another anti-war song and another song associated with Rose, also had a contested provenance.

He is buried in Brompton Cemetery in South-west London.

16. 5. 2011 |

read more...

« Later articles

Older articles »

[by Ken Hunt, London] Bass player Chris Ethridge (top right in photograph), who died on 23 April 2012 in his birth town of Meridian, Mississippi was one of the sidemen whose curriculum vitae was lit with musical magic and yet overshadowed in some way by one of his early excursions into working as a musician, even though he played bass with Willie Nelson during in the 1970s and 1980s.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Bass player Chris Ethridge (top right in photograph), who died on 23 April 2012 in his birth town of Meridian, Mississippi was one of the sidemen whose curriculum vitae was lit with musical magic and yet overshadowed in some way by one of his early excursions into working as a musician, even though he played bass with Willie Nelson during in the 1970s and 1980s. Two of that album’s strongest songs – Hot Burrito #1 and Hot Burrito #2 – carried joint Ethridge/Parsons compositional credits. For them alone, Ethridge is worthy of being remembered. Hot Burrito #1 went on to grace Elvis Costello’s Nashville Bash Almost Blue (1981) under the title I’m Your Toy with John McFee adding pedal steel guitar to the track. Ethridge went on to co-pen She with Gram Parsons. One of Gram Parsons’ most memorable vehicles, arguably Hot Burrito #1, Hot Burrito #2 and She are Parsons’ three greatest originals. Etheridge did not play on Parsons’ solo debut GP (1973).

Two of that album’s strongest songs – Hot Burrito #1 and Hot Burrito #2 – carried joint Ethridge/Parsons compositional credits. For them alone, Ethridge is worthy of being remembered. Hot Burrito #1 went on to grace Elvis Costello’s Nashville Bash Almost Blue (1981) under the title I’m Your Toy with John McFee adding pedal steel guitar to the track. Ethridge went on to co-pen She with Gram Parsons. One of Gram Parsons’ most memorable vehicles, arguably Hot Burrito #1, Hot Burrito #2 and She are Parsons’ three greatest originals. Etheridge did not play on Parsons’ solo debut GP (1973).  As a member of Willie Nelson’s touring band, he toured extensively as well as contributing to the Booker T. Jones-produced Stardust (1978). The album was a fine balancing act, for Nelson was not delivering what was necessarily expected of him with its covers of the Kurt Weill/Maxwell Anderson September Song, the Hoagy Carmichael/Stuart Gorrell Georgia On My Mind, the Jimmy McHugh/Dorothy Fields Sunny Side of the Street and the George Gershwin/Ira Gershwin Someone To Watch Over Me.

As a member of Willie Nelson’s touring band, he toured extensively as well as contributing to the Booker T. Jones-produced Stardust (1978). The album was a fine balancing act, for Nelson was not delivering what was necessarily expected of him with its covers of the Kurt Weill/Maxwell Anderson September Song, the Hoagy Carmichael/Stuart Gorrell Georgia On My Mind, the Jimmy McHugh/Dorothy Fields Sunny Side of the Street and the George Gershwin/Ira Gershwin Someone To Watch Over Me. [by Ken Hunt, London] The mridangam virtuoso Palghat T.S. Mani Iyer, born 100 years ago in Palghat (the anglicised version of Palakkad) in Kerala, was one of the musical giants of the Twentieth Century. Prior to him, the mridangam had filled the subordinate time- and tempo-supporting role – the usual role of drums in both of the subcontinent’s art music systems and folk traditions. He was one of a generation of musicians that changed the complexion of South Indian music.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The mridangam virtuoso Palghat T.S. Mani Iyer, born 100 years ago in Palghat (the anglicised version of Palakkad) in Kerala, was one of the musical giants of the Twentieth Century. Prior to him, the mridangam had filled the subordinate time- and tempo-supporting role – the usual role of drums in both of the subcontinent’s art music systems and folk traditions. He was one of a generation of musicians that changed the complexion of South Indian music. [by Ken Hunt, London] The Lovin’ Spoonful was a band that, in the most cool of manners, took its name from a Mississippi John Hurt recording. They made a music that brought together jug band (skiffle) music, folk and folk-blues with an added pop into rock sensibility around 1966 when nobody knew exactly what was going on and definitely nobody knew where it was all going to go.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Lovin’ Spoonful was a band that, in the most cool of manners, took its name from a Mississippi John Hurt recording. They made a music that brought together jug band (skiffle) music, folk and folk-blues with an added pop into rock sensibility around 1966 when nobody knew exactly what was going on and definitely nobody knew where it was all going to go. [by Ken Hunt, London] The Scottish folksinger Ray Fisher once told me that she had a series of scheduled performances in Czechoslovakia that were abruptly cancelled when the Soviet bloc forces had the bad manners to invade in 1968. The following year, rescheduled concerts finally took place. She recalled the mayor of one town greeting her. Two Soviet officers flanked him. The mood was tense. Then, one of them broke the ice by asking her excitedly whether she knew the Beatles. (With her winsome charm, no doubt she pulled it off effortlessly but alas I have no memory of how exactly she got out of that one.) As part of the cultural exchange, the tour introduced her to dudy – Czech bagpipes and ‘bagpipes’ in Czech – and she remembered the experience with wry fondness.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Scottish folksinger Ray Fisher once told me that she had a series of scheduled performances in Czechoslovakia that were abruptly cancelled when the Soviet bloc forces had the bad manners to invade in 1968. The following year, rescheduled concerts finally took place. She recalled the mayor of one town greeting her. Two Soviet officers flanked him. The mood was tense. Then, one of them broke the ice by asking her excitedly whether she knew the Beatles. (With her winsome charm, no doubt she pulled it off effortlessly but alas I have no memory of how exactly she got out of that one.) As part of the cultural exchange, the tour introduced her to dudy – Czech bagpipes and ‘bagpipes’ in Czech – and she remembered the experience with wry fondness. Born in Glasgow, Scotland on 26 November 1940, in 1962, she had married Colin Ross, the fiddler and piper, and later co-founder of the High Level Ranters, and settled in Tyneside. With her marriage to Colin, she was wed – or, as she sometimes joked – widowed to the pipes. She was one of six daughters – Jean, Joyce, Cindy, Audrey and Priscilla – and one token son – Archie – born into a family with catholic musical tastes that included light operatic and parlour fare (their father John Galbraith Fisher sang in the City of Glasgow police choir), Scots and, since their mother, Marion née MacDonald (known as Morag or Ma Fisher) had it as her mother tongue, Gaelic songs. Like many folkies of her generation, Britain’s skiffle movement was the springboard to a greater awareness of folk music. Through a fluke of fate and proximity, a bloke who owned a local record shop lent US import LPs on Folkways by Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, Buell Kazee and Aunt Samantha Bumgarner to Hamish Imlach, whose Cod Liver Oil and The Orange Juice – Reminiscences of a Fat Folk Singer – discusses the early Glasgow folk scene. Imlach borrowed them because he was the one with a record player that could play them.

Born in Glasgow, Scotland on 26 November 1940, in 1962, she had married Colin Ross, the fiddler and piper, and later co-founder of the High Level Ranters, and settled in Tyneside. With her marriage to Colin, she was wed – or, as she sometimes joked – widowed to the pipes. She was one of six daughters – Jean, Joyce, Cindy, Audrey and Priscilla – and one token son – Archie – born into a family with catholic musical tastes that included light operatic and parlour fare (their father John Galbraith Fisher sang in the City of Glasgow police choir), Scots and, since their mother, Marion née MacDonald (known as Morag or Ma Fisher) had it as her mother tongue, Gaelic songs. Like many folkies of her generation, Britain’s skiffle movement was the springboard to a greater awareness of folk music. Through a fluke of fate and proximity, a bloke who owned a local record shop lent US import LPs on Folkways by Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, Buell Kazee and Aunt Samantha Bumgarner to Hamish Imlach, whose Cod Liver Oil and The Orange Juice – Reminiscences of a Fat Folk Singer – discusses the early Glasgow folk scene. Imlach borrowed them because he was the one with a record player that could play them. Most important of all, many would consider, was Topic’s LP The Fisher Family, recorded in 1965 and released the following year. Its subtitle said ‘Traditional and New Songs from Scotland’. Bill Leader recorded it at the Fisher Family palace, while Joe Boyd, his assistant on the job (later to achieve other things through Witchseason, Island, Elektra, Reprise and more, but also the snapper that captured the cover image), slept in the car outside because there was no more room in the palace. At her funeral, her surviving sisters sang Ewan MacColl’s Come All Ye Fisher Lasses, the album’s opening track on which Ray had sung lead.

Most important of all, many would consider, was Topic’s LP The Fisher Family, recorded in 1965 and released the following year. Its subtitle said ‘Traditional and New Songs from Scotland’. Bill Leader recorded it at the Fisher Family palace, while Joe Boyd, his assistant on the job (later to achieve other things through Witchseason, Island, Elektra, Reprise and more, but also the snapper that captured the cover image), slept in the car outside because there was no more room in the palace. At her funeral, her surviving sisters sang Ewan MacColl’s Come All Ye Fisher Lasses, the album’s opening track on which Ray had sung lead. In 1991 she released her third and final solo album Traditional Songs of Scotland which complemented Saydisc’s English and Welsh companion volumes – Jo Freya’s Traditional Songs of England and Siwsann George’s Traditional Songs of Wales/Caneuon Traddodiadol Cymru. Its out-take Now Westlin’ Winds, with Martin Carthy accompanying on guitar, from the same sessions appeared on the seasonal round anthology, All Through The Year (Fledg’ling, 1991).

In 1991 she released her third and final solo album Traditional Songs of Scotland which complemented Saydisc’s English and Welsh companion volumes – Jo Freya’s Traditional Songs of England and Siwsann George’s Traditional Songs of Wales/Caneuon Traddodiadol Cymru. Its out-take Now Westlin’ Winds, with Martin Carthy accompanying on guitar, from the same sessions appeared on the seasonal round anthology, All Through The Year (Fledg’ling, 1991). Long associated with the Newcastle upon Tyne folk scene, whether ‘knitting’ bags for her pipe-maker husband’s much sought-after Northumbrian pipes or just singing or adding drolleries of the spoken monologue or parody song type, she appeared on 50 Years of Folk Music in Newcastle (Ceilidh Connections, 2009) performing her arch monologue Behave Yoursel’ – a treatise on declining standards in public places – and, accompanied by Tom Gilfellon on guitar, Generations of Change and Old Maid In A Garret. It was a no-frills double-CD celebrating a half-century of one of Britain’s finest folk hubs – the club that began as Folksong and Ballad before becoming the Bridge Folk Club and most especially known from its time at the Barras Bridge Hotel in the city. It ranked, I wrote in R2, as “one of the folk scene’s very most important outposts when the likes of Mike Waterson … willingly thumbed it from Hull to Liverpool (pre-motorway system) in order to visit the Spinners’ folk club.” I continued, “You get the club’s founding fathers – Johnny Handle and Louis Killen – in the glad company of past and present High Level Ranters (surely verging on the holotypic in a folk revival band sense and absolutely one of Britain’s finest), Chris Hendry, Ray Fisher, Pete Wood, John Brennan and others. … 50 Years of Folk Music in Newcastle brilliantly distils the essence of not merely one but this country’s whole folk club movement.”

Long associated with the Newcastle upon Tyne folk scene, whether ‘knitting’ bags for her pipe-maker husband’s much sought-after Northumbrian pipes or just singing or adding drolleries of the spoken monologue or parody song type, she appeared on 50 Years of Folk Music in Newcastle (Ceilidh Connections, 2009) performing her arch monologue Behave Yoursel’ – a treatise on declining standards in public places – and, accompanied by Tom Gilfellon on guitar, Generations of Change and Old Maid In A Garret. It was a no-frills double-CD celebrating a half-century of one of Britain’s finest folk hubs – the club that began as Folksong and Ballad before becoming the Bridge Folk Club and most especially known from its time at the Barras Bridge Hotel in the city. It ranked, I wrote in R2, as “one of the folk scene’s very most important outposts when the likes of Mike Waterson … willingly thumbed it from Hull to Liverpool (pre-motorway system) in order to visit the Spinners’ folk club.” I continued, “You get the club’s founding fathers – Johnny Handle and Louis Killen – in the glad company of past and present High Level Ranters (surely verging on the holotypic in a folk revival band sense and absolutely one of Britain’s finest), Chris Hendry, Ray Fisher, Pete Wood, John Brennan and others. … 50 Years of Folk Music in Newcastle brilliantly distils the essence of not merely one but this country’s whole folk club movement.”  [by Ken Hunt, London] To be truthful, there really have been very few disc jockeys who have changed society’s attitudes to music. Tom Donahue introduced a virus to North American radio programming. Donahue’s infected the San Francisco Bay Area. By circumventing conventional playlist conventions, he wove an unconventional tapestry that enabled listeners to think beyond the commercially regulated 45 rpm format, think about LP-length tracks as a format and thus to think for themselves. The pendulum had swung slow for too long and it needed adjusting because it was no longer in time with the times. John Peel did that too, only he took things further and took his catholic tastes and musical worldview to places far beyond an English recording studio.

[by Ken Hunt, London] To be truthful, there really have been very few disc jockeys who have changed society’s attitudes to music. Tom Donahue introduced a virus to North American radio programming. Donahue’s infected the San Francisco Bay Area. By circumventing conventional playlist conventions, he wove an unconventional tapestry that enabled listeners to think beyond the commercially regulated 45 rpm format, think about LP-length tracks as a format and thus to think for themselves. The pendulum had swung slow for too long and it needed adjusting because it was no longer in time with the times. John Peel did that too, only he took things further and took his catholic tastes and musical worldview to places far beyond an English recording studio. He was renowned for playing what he liked and generally liking and championing what he played (though sometimes he just played music that piqued his curiosity because he knew he was undecided enough about it to give it the benefit of the doubt). Arguably, he was the most important music broadcaster of his time in the world. If that curdles anyone’s milk, name the pretender to that throne.

He was renowned for playing what he liked and generally liking and championing what he played (though sometimes he just played music that piqued his curiosity because he knew he was undecided enough about it to give it the benefit of the doubt). Arguably, he was the most important music broadcaster of his time in the world. If that curdles anyone’s milk, name the pretender to that throne. He went on to BBC Radio One ushering in a period and patronage of acts such as the Undertones, Frank Chickens, Henry Cow, Oasis, Blur and worse. Droll, open and witty to an extreme, he gave exposure to generations of culturally significant music, without fear or (much) favour. His producer, John Walters once archly observed, “If Peely ever reaches puberty, we’re all in trouble.” He never sprouted musical pubes, thank heavens. He did, however, speak frankly about the consequences of carefree promiscuity in the pre-AIDS years. He remains a hero.

He went on to BBC Radio One ushering in a period and patronage of acts such as the Undertones, Frank Chickens, Henry Cow, Oasis, Blur and worse. Droll, open and witty to an extreme, he gave exposure to generations of culturally significant music, without fear or (much) favour. His producer, John Walters once archly observed, “If Peely ever reaches puberty, we’re all in trouble.” He never sprouted musical pubes, thank heavens. He did, however, speak frankly about the consequences of carefree promiscuity in the pre-AIDS years. He remains a hero. [by Ken Hunt, London] Patrick Galvin’s death on 10 May 2011 in his birth city of Cork received some attention, the way that Ireland’s foremost poets and men-of-letters get written up. Born on 15 August 1927, his obituaries raised the response of ‘Oh no, that will not do.’ Galvin was more than a poet and dramatist in the way he chronicled and portrayed his homeland, its history and its people. He had a parallel life as a singer and writer of Irish songs. His recording career began at Topic – Britain’s and the world’s oldest independent record label – in the early 1950s. He contributed a number of 78 rpm singles with Al Jeffrey, an early largely unsung hero of the post-war Folk Revival, accompanying him. Amongst them, were songs now largely seen as, or deemed standard repertoire through, say, the Dubliners, Thin Lizzy and Sinéad O’Connor.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Patrick Galvin’s death on 10 May 2011 in his birth city of Cork received some attention, the way that Ireland’s foremost poets and men-of-letters get written up. Born on 15 August 1927, his obituaries raised the response of ‘Oh no, that will not do.’ Galvin was more than a poet and dramatist in the way he chronicled and portrayed his homeland, its history and its people. He had a parallel life as a singer and writer of Irish songs. His recording career began at Topic – Britain’s and the world’s oldest independent record label – in the early 1950s. He contributed a number of 78 rpm singles with Al Jeffrey, an early largely unsung hero of the post-war Folk Revival, accompanying him. Amongst them, were songs now largely seen as, or deemed standard repertoire through, say, the Dubliners, Thin Lizzy and Sinéad O’Connor. [by Ken Hunt, London] The outstanding, trail-blazing Hindustani violinist Vishnu Govind Jog, usually known more simply as V.G. Jog, died in Kolkata (Calcutta) on 31 January 2004. He had been born in Bombay (now Mumbai), then in the Bombay Presidency (nowadays Maharashtra) in 1922. He received his early music training from several notables, amongst them, S.C. Athavaic, Ganpat Rao Purohit and Dr. S.N. Ratanjarkar, but where he differed from most of his contemporaries was his espousal and championing of the violin played in Indian tuning. To the north of the subcontinent, the European violin had little status. Professor V.G. Jog was a major force in correcting violinistic misperceptions. In Hindustani music the violin had (and has) to compete with the sarangi, an instrument of rare subtlety, capable of splitting the microtonal atom, as it were.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The outstanding, trail-blazing Hindustani violinist Vishnu Govind Jog, usually known more simply as V.G. Jog, died in Kolkata (Calcutta) on 31 January 2004. He had been born in Bombay (now Mumbai), then in the Bombay Presidency (nowadays Maharashtra) in 1922. He received his early music training from several notables, amongst them, S.C. Athavaic, Ganpat Rao Purohit and Dr. S.N. Ratanjarkar, but where he differed from most of his contemporaries was his espousal and championing of the violin played in Indian tuning. To the north of the subcontinent, the European violin had little status. Professor V.G. Jog was a major force in correcting violinistic misperceptions. In Hindustani music the violin had (and has) to compete with the sarangi, an instrument of rare subtlety, capable of splitting the microtonal atom, as it were. To give a few entry points, try his out-of-print jugalbandi (duet) with the shehnai (shawm) maestro Bismillah Khan for EMI’s ‘Music From India Series’. More readily available are his duets with the guitarist Brijbhushan Kabra for the German Chhanda Dhara label (1988) and the santoor player Tarun Bhattacharya for Nataraj Music (1993). In a solo sphere, his renditions of his namesake raga – Jog – for Moment (1991), his 1981 recording of Kirwani and Kajri for Navras (1996) or his All India Radio-derived recordings in T Seroes’ Immortal Series are good entry points. Anybody interested in the violin’s potential should listen to him. One of the great, great masters.

To give a few entry points, try his out-of-print jugalbandi (duet) with the shehnai (shawm) maestro Bismillah Khan for EMI’s ‘Music From India Series’. More readily available are his duets with the guitarist Brijbhushan Kabra for the German Chhanda Dhara label (1988) and the santoor player Tarun Bhattacharya for Nataraj Music (1993). In a solo sphere, his renditions of his namesake raga – Jog – for Moment (1991), his 1981 recording of Kirwani and Kajri for Navras (1996) or his All India Radio-derived recordings in T Seroes’ Immortal Series are good entry points. Anybody interested in the violin’s potential should listen to him. One of the great, great masters. [by Ken Hunt, Berlin] On 30 December 2003, Tanzania’s internationally best-known musician, Hukwe Zawose died at home in Bagamoyo, his musical base for many decades, at the age of 65. Tanzanian music never had much of an international profile outside of ethnography until Hukwe Zawose but when it arrived it arrived in style.

[by Ken Hunt, Berlin] On 30 December 2003, Tanzania’s internationally best-known musician, Hukwe Zawose died at home in Bagamoyo, his musical base for many decades, at the age of 65. Tanzanian music never had much of an international profile outside of ethnography until Hukwe Zawose but when it arrived it arrived in style. Born in 1938 in Doduma, a rural district in central Tanganyika, as it was then known, he had an active recording career outside his homeland, recording for Real World, the Tokyo-based Seven Seas/King Record Co, Triple Earth (the London-based label that brokered and oversaw his international breakthrough) and WOMAD Select (notably the Mkuki Wa Rocho (A Spear To The Soul) album, 2002). Even if most people never bothered to learn about Wagogo as opposed to Tanzanian culture, Zawose became the one name that people remembered when it came to Tanzania’s folkways or, cynically mumbled, its ‘World Music’.