Lives

[by Ken Hunt, London] Record shops held a particular status in the cultural to-and-fro of earlier times in ways that would be impossible to explain in the internet age. It was pretty much in order to go to a shop with minimal cash (remember, this is pre-plastic) and listen to a whole LP with only the flimsiest justification or intention of purchasing it.

9. 5. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] British folk music found a top drawer brass player, arranger and composer in Howard Evans. He had an utterly pragmatic, utterly professional attitude to music making and the musician’s life and from 1997, when he joined the Musicians Union’s London headquarters, as assistant general secretary for media he revealed that over and over again. He was totally pragmatic about his art and the first to drolly prick any bubbles of pretension about making music. He brought a wider knowledge and a greater diversity of musical experiences to bear on making music than any professional musician I ever met but he never got the slightest tan from the musical limelight.

[by Ken Hunt, London] British folk music found a top drawer brass player, arranger and composer in Howard Evans. He had an utterly pragmatic, utterly professional attitude to music making and the musician’s life and from 1997, when he joined the Musicians Union’s London headquarters, as assistant general secretary for media he revealed that over and over again. He was totally pragmatic about his art and the first to drolly prick any bubbles of pretension about making music. He brought a wider knowledge and a greater diversity of musical experiences to bear on making music than any professional musician I ever met but he never got the slightest tan from the musical limelight.

He mixed years of experience playing brass in military music contexts with the Welsh Guards, in pit orchestras, in London shows such as Cats, Starlight Express and Lou Reizner’s production of The Who’s Tommy and for sessions for the likes of the Star Wars soundtrack, Rick Wakeman, Emerson, Lake & Palmer Evans and the André Previn-era London Symphony Orchestra. Apart from the LSO, he played with the Royal Ballet, Welsh Opera and, most pertinently for his folk connections, with the National Theatre (NT) (as it was called before it got a ‘Royal’ appendage stuck at its front).

He mixed years of experience playing brass in military music contexts with the Welsh Guards, in pit orchestras, in London shows such as Cats, Starlight Express and Lou Reizner’s production of The Who’s Tommy and for sessions for the likes of the Star Wars soundtrack, Rick Wakeman, Emerson, Lake & Palmer Evans and the André Previn-era London Symphony Orchestra. Apart from the LSO, he played with the Royal Ballet, Welsh Opera and, most pertinently for his folk connections, with the National Theatre (NT) (as it was called before it got a ‘Royal’ appendage stuck at its front).

He brought this to bear when playing with Martin Carthy and John Kirkpatrick, Brass Monkey and the Home Service. Born in Chard, Somerset in England’s West Country on 29 February 1944, he died in North Cheam in Surrey on 17 March 2006. He first picked up a brass instrument (“baritone sax horn,” he told Owen Jones’ short-lived folk magazine Albion Sunrise, “it was actually a tenor sax horn”) when he was 10 and eventually graduated to cornet. At the age of 13 he passed an audition to play with the National Youth Brass Band. He left school aged 15. In 1961, after a couple of years of scratching a non-musical living, he responded to an advert in the UK magazine British Bandsman for experienced cornet players. The Welsh Guards recruited him on talent and because he father was Welsh. Nine years as a bandsman with the Welsh Guards followed and later drew on this experience with choice morsels such as Old Grenadier in Brass Monkey’s repertoire or the inclusion of Percy Grainger’s Lincolnshire Posy in the Home Service’s repertoire. They illuminated the British folk scene. He also did sessions for the likes of Leon Rosselson and Loudon Wainwright III. He just regarded himself as a musician, not a folk musician or any other musical subgenre.

Howard Evans could play anything brassy, whether trumpet, cornet, flugelhorn or, on one occasion in an NT production, alpenhorn. He was a total musician as happy analysing Miles Davis’ Sketches of Spain or Dave Brubeck’s ‘Take Five’ as a little Percy Grainger or something from The Who. He had managed to get a foot inside the NT pit in the 1970s with Tales From The Vienna Woods. Productions such as The Plough And The Stars and Sir Gawain & The Green Knight tumbled after, leading to the invitation to join Ashley Hutchings’ post-Rise Up Like The Sun Albion Band, then preparing for the Bill Bryden’s production of Lark Rise in the NT’s Cottesloe Theatre. The NT’s ‘Green Room’ was renowned for its conviviality. Out of one conversation came the offer for him to work with the guitarist and vocalist Martin Carthy and the free reed maestro and vocalist John Kirkpatrick. It seemed a good idea. The first fruits of their newly hatched partnership were him overdubbing trumpet on Jolly Tinker and Lovely Joan on Carthy’s Because It’s There (1979). By January 1980 they were out gigging as a three-piece which was when I first met him.

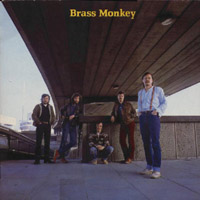

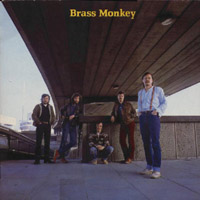

That trio grew and in January 1981 metamorphosed into a fresh elemental force eventually called Brass Monkey, an idiom open to various interpretations, as a quintet with Martin Brinsford playing sax, mouthorgan and percussion and Roger Williams trombone, occasionally tuba and euphonium. They stayed together, apart from a period in which Richard Cheetham occupied the trombone chair Williams rejoined. Their head-turning Brass Monkey (1983) (now combined with their second LP See How It Runs (1986) – derived from the Saxa Salt catchphrase – as The Complete Brass Monkey (1993)) contains a remarkable reworking of the incest ballad The Maid And The Palmer, one of the most daring and mesmerising performances ever committed to posterity or perdition. The combination of Evans, Williams and Brinsford playing together will be etched into anyone’s memory who saw them. They were that potent a force. Brass Monkey went on to make five albums with Sound & Rumour (1998), Going & Staying (2001) and Flame of Fire (2004). It was while touring with Brass Monkey that Evans fell ill. He was diagnosed as having cancer. We spoke afterwards and he confessed to an initial rush of ‘Why me?’ thoughts, soon eclipsed, typically, by a ‘Why not me?’ reflection.

That trio grew and in January 1981 metamorphosed into a fresh elemental force eventually called Brass Monkey, an idiom open to various interpretations, as a quintet with Martin Brinsford playing sax, mouthorgan and percussion and Roger Williams trombone, occasionally tuba and euphonium. They stayed together, apart from a period in which Richard Cheetham occupied the trombone chair Williams rejoined. Their head-turning Brass Monkey (1983) (now combined with their second LP See How It Runs (1986) – derived from the Saxa Salt catchphrase – as The Complete Brass Monkey (1993)) contains a remarkable reworking of the incest ballad The Maid And The Palmer, one of the most daring and mesmerising performances ever committed to posterity or perdition. The combination of Evans, Williams and Brinsford playing together will be etched into anyone’s memory who saw them. They were that potent a force. Brass Monkey went on to make five albums with Sound & Rumour (1998), Going & Staying (2001) and Flame of Fire (2004). It was while touring with Brass Monkey that Evans fell ill. He was diagnosed as having cancer. We spoke afterwards and he confessed to an initial rush of ‘Why me?’ thoughts, soon eclipsed, typically, by a ‘Why not me?’ reflection.

Working in the NT brought him into contact with an eleven-piece Albion Band offshoot rehearsed from November 1980 and March 1981 near the NT while working on The Passion. The tentatively titled First Eleven chrysalis included Evans and Kirkpatrick. The group that finally emerged, a mere septet, was the Home Service, England’s most forceful electrified folk group Fairport Convention and Steeleye Span. They created a never-before-heard sound live. Even if their debut Home Service (1984) failed to deliver the band’s power and majesty, it revealed the power of their songwriting and arranging. The Mysteries (1985) with Linda Thompson as guest vocalist was a marked improvement but still tied them to their NT sinecure. They broke free with their masterful Alright Jack (1986). Evans shaped the work mightily, suggesting Percy Grainger’s Lincolnshire Posy, a suite he had encountered with the Welsh Guards. In the mixing room a copy of John Bird’s biography of Grainger was a fixture, a touch I loved.

At the 1982 Cambridge Folk Festival, whilst sitting with the writers Richard Hoare and the John Platt, that West Coast man of many strings David Lindley first heard an act billed as the Martin Carthy Band. A couple of years later, he told me, “It was the most exciting, original thing I’d heard in ten years.” Their proper name was Brass Monkey. Nobody had ever combined voice, stringed and free reed instruments, percussion, reed and brass instruments like Brass Monkey before. Maybe nobody had ever imagined that combination in its blending of folk and wind bands. At Jackson Browne and David Lindley’s Theatre Royal concert in London on 27 March 2006, Lindley called Brass Monkey “one of my favourite bands of all time” and dedicated El Rayo-X to Howard Evans saying “This song is supposed to have horns in it. He’ll be playing.”

At the 1982 Cambridge Folk Festival, whilst sitting with the writers Richard Hoare and the John Platt, that West Coast man of many strings David Lindley first heard an act billed as the Martin Carthy Band. A couple of years later, he told me, “It was the most exciting, original thing I’d heard in ten years.” Their proper name was Brass Monkey. Nobody had ever combined voice, stringed and free reed instruments, percussion, reed and brass instruments like Brass Monkey before. Maybe nobody had ever imagined that combination in its blending of folk and wind bands. At Jackson Browne and David Lindley’s Theatre Royal concert in London on 27 March 2006, Lindley called Brass Monkey “one of my favourite bands of all time” and dedicated El Rayo-X to Howard Evans saying “This song is supposed to have horns in it. He’ll be playing.”

At Howard Evans’ packed ‘leaving do’, the remaining four Monkeys played him out with Old Grenadier, one of pieces he had brought to the band’s table at the beginning.

Very much in Howard Evans’ memory, Brass Monkey continues to perform. Paul Archibald, on trumpets, piccolo trumpet and cornets, debuted live in March 2009 at the Electric Theatre in Guildford, Surrey playing a repertoire that included material from Brass Monkey’s then-unreleased Head of Steam (2009).

The Home Service album sleeve image is © and courtesy of Fledg’ling Records. The album sleeves and images of Brass Monkey are © and courtesy of Topic Records. In the first photo by John Haxby they are L-R: Martin Brinsford, Martin Carthy (below), John Kirkpatrick (above), Roger Williams and Howard Evans. In the second they are Martin Carthy, Howards Evans, Martin Brinsford, John Kirkpatrick and Richard Cheetham.

14. 3. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Terry Melcher, who died of cancer on 19 November 2004, was a man of many parts and, as Doris Day’s son, doors opened for him. Her only son, he was born Terry Jorden on 8 February 1942. Taking the surname of his mother’s third husband, Martin Melcher (who legally adopted him), he helped shape a generation’s musical consciousness and define the West Coast folk-rock sound. Before that he wrote songs, for instance, with Bobby Darin and Randy Newman, for his mother and for Paul Revere and the Raiders (for whom he penned Him Or Me (What’s It Gonna Be)).

[by Ken Hunt, London] Terry Melcher, who died of cancer on 19 November 2004, was a man of many parts and, as Doris Day’s son, doors opened for him. Her only son, he was born Terry Jorden on 8 February 1942. Taking the surname of his mother’s third husband, Martin Melcher (who legally adopted him), he helped shape a generation’s musical consciousness and define the West Coast folk-rock sound. Before that he wrote songs, for instance, with Bobby Darin and Randy Newman, for his mother and for Paul Revere and the Raiders (for whom he penned Him Or Me (What’s It Gonna Be)).

Melcher had a stint of songwriting and performing with the future Beach Boy Bruce Johnson (as Bruce & Terry) which led to a minor 1964 hit, Summer Means Fun, later singing back-ups on the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds (1966) and still later co-writing their US number single 1, Kokomo. Friendship with Dennis Wilson brought him into the orbit of the psychopathic killer Charles Manson, then an aspiring recording artist. After Manson and his Legion of Charlies turned Melcher’s former Hollywood home into a human abattoir for its new tenants in 1969, Melcher understandably flipped out.

Melcher had got on a programme for trainee producers for Columbia’s New York ‘office’ on the strength of a recording and when he returned to the West Coast, he wound up with a new band that had undergone a number of name changes from the Jet Set and the Beefeaters before arriving at the Byrds as their name. They were on the cusp of recording their Columbia debut. As David Fricke wrote in the Byrds’ box-set booklet notes, this was a time “when record labels and producers treated most pop groups like haircuts-with-attitude.” Mother Melcher knew best (and egos apart, he probably did) choosing Jim (later Roger) McGuinn and his 12-string to do the biz on Mr Tambourine Man. This had started out as pop music, after all. By the time the song was topping the charts round the world, the world was a different place. Melcher produced the hit-single album of the same name (1965) and the follow-up, Turn! Turn! Turn! (1966). After which the Byrds asserted themselves with the lusciousness of proven ‘lucrebility’ by dumping him. Melcher never completely left the Byrdish circle however, returning to produce the lacklustre The Ballad of Easy Rider (1969) (though that surely should have been ‘Ryder’ like their mooted album title Byrdshyt), the stupendous (untitled) (1970) and the reprehensibly crap Byrdmaniax (1971). He may have plagued us with solo albums (Terry Melcher (1974) and Royal Flush (1976) anyone?), but it for his guiding hand on the Byrdish tiller that we remember him here with extraordinary fondness.

21. 2. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Bengali singer Suchitra Mitra died on 3 January 2011 at her home of many years, Swastik on Gariahat Road in Ballygunge, Kolkata. She was famed as one of the heavyweight interpreters of the defining Bengali-language song genre form called Rabindra sangeet – or Rabindrasangeet (much like the name Ravi Shankar can also be rendered Ravishankar). ‘Rabindra song’ is an eloquent, literary, light classical song form, derived from the name of the man who ‘invented’ it, Rabindranath Tagore, the winner of the 1913 Nobel Prize for Literature.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Bengali singer Suchitra Mitra died on 3 January 2011 at her home of many years, Swastik on Gariahat Road in Ballygunge, Kolkata. She was famed as one of the heavyweight interpreters of the defining Bengali-language song genre form called Rabindra sangeet – or Rabindrasangeet (much like the name Ravi Shankar can also be rendered Ravishankar). ‘Rabindra song’ is an eloquent, literary, light classical song form, derived from the name of the man who ‘invented’ it, Rabindranath Tagore, the winner of the 1913 Nobel Prize for Literature.

Tagore’s songs helped define Bengali and Bangladeshi culture and identity – and importantly pan-Indian culture – in the years before the dissolution of the British Raj and afterwards. He died in 1941 and it was a cause of immense regret that she began her studies at Tagore’s Santiniketan – meaning ‘abode of peace’ – days after his death without having met him. However, she did study with some of the illustrious, next-generation exponents of the form in situ.

Although Suchitra Mitra will be remembered as one of the greatest ever interpreters of the Rabindra sangeet song form, she was massively important for her championing of Tagore as a cultural icon – for once the cliché ‘cultural icon’ is justified. She danced in Rabindra Nritya Natyas – his dance dramas -, taught and wrote about him and his works. She became one of the great authorities on him and his art.

She was born in what was then known as Central India Agency in British India on 19 September 1924. At the time her mother was on a train and for some reason was too preoccupied to note where exactly.

Regrettably the photo copyright information and the photographer’s name are unknown. We will correct this and/or remove the image when known.

31. 1. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Bengal’s popular arts lost two of its major figures on 17 January 2011.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Bengal’s popular arts lost two of its major figures on 17 January 2011.

The actress Gita Dey (1931-2011) died in north Kolkata. From her debut as a child actor in 1937 in director Dhiren Ganguly’s film Ahutee, she reportedly appeared in some 200 Bengali films and thousands of stage dramas and folk plays. A startling character actress with a presence that did not overwhelm the part, she appeared in such films as film director Ritwik Ghatak’s Meghe Dhaka Tara (1957), Satyajit Ray’s Teen Kanya and Komal Gandhar, and Tapan Sinha’s Haatey Baajarey, Jotugriha and Ekhonee. Lawrence Olivier was amongst the people who celebrated her.

The singer Pintu Bhattacharya’s death some five hours later at the Thakurpukur Hospital in south Kolkata was slightly overshadowed by that of his contemporary. He was an exponent of popular Bengali modern song (as it is known) and worked with many of the Bengali film industry’s foremost music directors including Salil Chowdhury (1922-1995) and for a range of film directors, including Tapan Sinha. Although he was something of a household name in Bengal, he was little known outside the region – a great shame for someone blessed with such a wondrous voice and interpretative skills. A big fish in a small pond, he was later sidelined by the Tollygunge film industry.

24. 1. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] One of my fondest memories of Britain’s specialised music magazine scene of the 1980s into the 1990s is how little ego and rivalry there was for the most part. There were a couple of exceptions (no names, no pack drill) and, strange though it may seem, not a single ornery person from that bunch stayed the course within music criticism. Keith Summers wrote about music, collected it (as in, made field recordings of such as Jumbo Brightwell, the Lings of Blaxhall, Cyril Poacher and Percy Webb as well as later contributing to Topic’s multi-volume series Voice of the People) and published magazines about it. He had the fall-back trade of accountant that funded his passions.

[by Ken Hunt, London] One of my fondest memories of Britain’s specialised music magazine scene of the 1980s into the 1990s is how little ego and rivalry there was for the most part. There were a couple of exceptions (no names, no pack drill) and, strange though it may seem, not a single ornery person from that bunch stayed the course within music criticism. Keith Summers wrote about music, collected it (as in, made field recordings of such as Jumbo Brightwell, the Lings of Blaxhall, Cyril Poacher and Percy Webb as well as later contributing to Topic’s multi-volume series Voice of the People) and published magazines about it. He had the fall-back trade of accountant that funded his passions.

In 1983 Summers launched an excellent magazine called Musical Traditions. A number of us already knew him from concerts or shindigs but issue one gave an idea of how he meant to continue and of his wider tastes with pieces on the Nigerian juju musician I.K. Dairo, the Irish piper, storyteller and folklorist Séamus Ennis, East Anglia’s wondrous traditional singer Walter Pardon and the Armenian musician Reuben Sarkasian. Many of the magazines that we published were basically one-man shows. Few lasted too long. The attrition rate due to bad debts, lost consignments and volunteer labour stretched too far did for many of us. Musical Traditions lasted for twelve physical issues. Yet, as if putting out one magazine wasn’t enough, Summers started up Keskidee, devoted to black music traditions. It managed three issues.

Summers was drawn to the Irish folk tradition. He recorded extensively between 1977 and 1983 in Co. Fermanagh in Northern Ireland. It culminated in his two-CD set, The Hardy Sons of Dan (Musical Traditions MTCD329-0, 2004), subtitled “Football, Hunting and Other Traditional Songs from around Lough Erne’s Shore”, with a collection of performances by the likes of James and Paddy Halpin, Packie McKeaney and Maggie Murphy.

One underreported aspect of dear old Keith was his own idiosyncratic singing. I remember it rather fondly. Like yesterday in fact. It was rather as if he had just staggered out of an Essex or Sarf London pub after a Sunday lunchtime session on the way to the figuratve seafood stall. (Back in those dark Sundays pubs were open for a measly two hours and then closed until the evening.) By way of background to the following anecdote, Keith and I had been to an exceedingly fine concert as part of the Crossing the Border festival the previous night. Lyle Lovett had sung his then unreleased I Married Her Just Because She Looks Like You (later to appear on Lyle Lovett And His Large Band (1989)). On the way out, full of Lebensfreude, we gazed into each other’s eyes and, without cue, Summers and Hunt broke into song – well, more the chorus which was pretty much the song’s title.

The next afternoon Keith and I found ourselves at the same press bash in the capital – the act, occasion and purpose banished and blotted out by the event’s free alcohol and the passing years. It having nothing to do with Lyle Lovett is all I remember. We did our damnest to help the cullet mountain by drinking uncounted bottles of foreign lager of export strength. Having done our bit for recycling and, importantly, having made sure there was no more to be had, we strolled down Tottenham Court Road in the sunshine hammily singing Lyle’s fine new song as an alcohol-acoustic loop all the way to Collet’s folk emporium at the top of Charing Cross Road where we treated the folk department’s manager, Gill Cook to several rousing loops of the same. She took it in good spirits, sat us down, made us tea and we talked. Cunning sangsters that we were, we kept the conversation flowing until about ten minutes before pub opening time. This coincided with the shop shutting, when the three of us swanned down to the nearby Angel at St. Giles High Street for liquid refreshments. Let’s not beat about the bush, damn it, that sunny afternoon Keith and I were Lyle Lovett’s right-hand men. He was Essex Lyle. I was Sarf London Lyle.

Born on a London double-decker bus outside Hackney General Hospital in, Hackney, East London on 11 December 1948, Keith Summers died at Southend-on-Sea, Essex on 30 March 2004.

There is a wonderful account of The Hardy Sons of Dan at www.mustrad.org.uk/articles/hardyson.htm

Ken Hunt’s obituary of Keith Summers is at www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/keith-summers-549731.html

16. 1. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Polish revue artist, singer and actress Irena Anders, born Irena Renata Jarosiewicz on 12 May 1920 in Bruntál, in what is nowadays the Czech Republic, went under the stage name of Renata Bogdańska. Her father was a Rutherian pastor while her mother came from the Polish gentry. She studied music formally at the National Academy of Music in Lviv. The invasion of Poland in September 1939 put paid to her studies and over the next few years the tides of war and the various fortunes of Poland, its citizens and army determined her own life’s course.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Polish revue artist, singer and actress Irena Anders, born Irena Renata Jarosiewicz on 12 May 1920 in Bruntál, in what is nowadays the Czech Republic, went under the stage name of Renata Bogdańska. Her father was a Rutherian pastor while her mother came from the Polish gentry. She studied music formally at the National Academy of Music in Lviv. The invasion of Poland in September 1939 put paid to her studies and over the next few years the tides of war and the various fortunes of Poland, its citizens and army determined her own life’s course.

Her first husband, Gwidon Borucki, led a morale-boosting troupe entertaining Polish forces fighting on the side of the Allies. Poles of the 2nd Polish Division under the command of General Władysław Anders played an especially important role in the hard-fought and bloody taking of the Nazi-occupied strongpoint at Monte Casino in Italy in 1944. Out of this campaign emerged the patriotic song Czerwone maki (na Monte Cassino) (‘Red Poppies On Monte Cassino’), which had a setting by Alfred Schütz of Feliks Konarski’s words. The song, composed in May 1944, was forged in the heat of that battle while the poppy image also evoked the symbol of trench warfare during the Great War. Czerwone maki was sung following the capture of the monastery and while there is a certain lack of clarity about Renata Bogdańska’s participation at this point, it became a song closely associated both with her, the anti-fascist movement and Polish patriotism.

She went on to marry Władysław Anders, settle in Britain, appear on radio and in films and in 2007 received Poland’s second highest civilian decoration for her contributions to Polish culture. She died on 29 November 2010 in London.

19. 12. 2010 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] “Ten years ago on a cold dark night/Someone was killed ‘neath the town hall lights./There were few at the scene, but they all did agree/that the man who ran looked a lot like me.”

[by Ken Hunt, London] “Ten years ago on a cold dark night/Someone was killed ‘neath the town hall lights./There were few at the scene, but they all did agree/that the man who ran looked a lot like me.”

When those renegades from Canadian justice, The Band made their début album Music From Big Pink in 1968, they included a timeless-sounding song called Long Black Veil that they had learned from Leftie Frizzell, on whose 1959 version Marijohn Wilkin played piano. It had an eerie, old-time, murder ballad guilt to it and many people thought it was traditional. Marijohn Wilkin, the woman who set Danny Dill’s lyrics to music, to produce Long Black Veil died, aged 86, on 28 October 2006.

Long Black Veil (1959) was supposedly nudged into existence by the story of a woman who haunted silent era heartthrob Rudolph Valentino’s graveside. Whether it was a ghostly or a figurative haunting remains the ectoplasm of story repetition, it touched is a sublime piece of haunting. After Leftie Frizzel, a litany of musicians covered including Burl Ives (too regularly marginalised but a major, major influence in folk circles), the Kingston Trio, Joan Baez, Johnny Cash, The Band, the New Riders of the Purple Sage and with The Chieftains with Mick Jagger.

Long Black Veil (1959) was supposedly nudged into existence by the story of a woman who haunted silent era heartthrob Rudolph Valentino’s graveside. Whether it was a ghostly or a figurative haunting remains the ectoplasm of story repetition, it touched is a sublime piece of haunting. After Leftie Frizzel, a litany of musicians covered including Burl Ives (too regularly marginalised but a major, major influence in folk circles), the Kingston Trio, Joan Baez, Johnny Cash, The Band, the New Riders of the Purple Sage and with The Chieftains with Mick Jagger.

She was born Marijohn Melson on 14 July 1920, the only child of Ernest and Karla, she was raised in Kemp, Texas. She relocated to Nashville around 1958 and had some minor chart success when Wanda Jackson covered her No Wedding Bells For Joe (1959), followed the same year by major chart action with Waterloo sang by Stonewall Jackson, co-written with John D. Loudermilk. Its chorus went, “Waterloo, Waterloo/Where will you meet your Waterloo?/Every puppy has its day/Everybody has to pay/Everybody has to meet his Waterloo.” (So no Long Black Veil.)

For a songwriter, their importance is, of course, measured by their songs and frequently by the stature of people who cover songs. Apart from the afore-mentioned, hers included Cut Across Shorty and One Day At A Time and Ann-Margret, The Beatles, Glen Campbell, Patsy Cline, Eddie Cochran and Rod Stewart. Not a bad little bead-roll.

Furthermore, she was also part of the process that brought Kris Kristofferson to people’s attention by signing the aspirant songwriter in 1965. She made records under her own name and wrote an autobiography called Lord Let Me Leave A Song (1978). As that title might suggest, she became a mite active in the Christian music industry.

22. 11. 2010 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] People’s appreciation of American folk music did not commence with the folk scare of the 1960s and the likes of the Kingston Trio, Peter, Paul and Mary, Joan Baez, Odetta, Buffy Sainte-Marie and Bob Dylan. A generation before them another folk revival, that similarly had no truck with segregation along racial lines, had been under way. Its crop of performers included progressives such as Josh White, Woody Guthrie, Huddie ‘Leadbelly’ Ledbetter and Pete Seeger. Like the next generation, the earlier one wrote new songs in various folk idioms, frequently darts with left-leaning barbs, dosed with class consciousness and social awareness.

[by Ken Hunt, London] People’s appreciation of American folk music did not commence with the folk scare of the 1960s and the likes of the Kingston Trio, Peter, Paul and Mary, Joan Baez, Odetta, Buffy Sainte-Marie and Bob Dylan. A generation before them another folk revival, that similarly had no truck with segregation along racial lines, had been under way. Its crop of performers included progressives such as Josh White, Woody Guthrie, Huddie ‘Leadbelly’ Ledbetter and Pete Seeger. Like the next generation, the earlier one wrote new songs in various folk idioms, frequently darts with left-leaning barbs, dosed with class consciousness and social awareness.

The musician, songwriter and folklorist Bess Lomax Hawes, who died in Portland, Oregon on 28 November 2009, was one of those musicians and songwriters whose worldview coloured, most notably, the Almanac Singers – the template and forerunner for the United States’ first commercially successful and internationally influential folk supergroup, The Weavers. And she may have helped colour yours.

Bess Hawes, born in Austin, Texas on 21 January 1921 came from a Texican family that boasted two of the most important figureheads in the new folk movement. Only the Seegers, as it were, aced them. Her father was the folklorist and musicologist John A. Lomax (1867-1948) and her name derived from her mother, Lomax’s first wife, Bess Baumann, née Brown (1881-1931). Bess Hawes’ brother Alan (1915-2002), six years and some days her senior, became one of the foremost ethnomusicologists of the post-Second World War years in his own right. Her fate was sealed. “Folkloring,” she wrote, “in those days was a family affair.”

Her exclusive Hockaday School education, under financial pressure, made or gave way to a “slum school” with a high Mexican-American intake. Nolan Porterfield, her father’s biographer, quotes her saying, “I was well ahead of them in school terms, but they were ahead of me in life terms. It had a very profound affect [sic] on me – it developed my social attitudes for the rest of my life.” After finishing her education at Bryn Mawr College in 1941 – excessive absenteeism had placed her on probation – she cut out for the wilds of New York City.

There she found herself in the company of a bunch of like-minded people that coalesced as the Almanac Singers. Scratching for a living with odd gigs in small venues, before union congregations, some radio work and some recording, they were yet to become legendary. She was the only one with a regular income, a salary. Their living arrangements bore out their financial fragility. Renting a communal townhouse on Greenwich Village’s Sixth Avenue, Woody Guthrie lived there. Space was so cramped that she and Pete Seeger shared the same attic room. Decorously, in order to divide and maintain the platonic nature of their quarters, a curtain separated them.

She never let on, to use the vernacular, that she had the hots for Seeger. Yet their chaste relationship could never stand up to her father’s inspection. Getting wind of an impending ‘inspection’ she barely had time to move her belongings before he was fuming at the door and Seeger redirected him. In any case, soon afterwards – in 1942 – she married one of the musicians within the Almanacs’ circle, the photographer and musician Butch Hawes, with whom she had two daughters and one son.

Most of her songs served next to no time. Their time came and went in a trice in the manner of the times. Often she – and the Almanacs – simply took a familiar or public-domain melody and wrote new words to it for a strike, a demonstration or a session. One, however, definitely endured. She and Jacqueline Steiner wrote a campaign song for Walter A. O’Brian, Boston’s Progressive Party candidate for mayor in 1949 about a stranded commuter on the Massachusetts Transit Authority who can’t get off the train because he doesn’t have the excess fare. It became a transferrable commuter hymn that could equally apply to Boris Johnson and Transport For London’s price hikes.

“Well, let me tell you of the story of a man named Charlie.

On a tragic and fateful day,

He put ten cents in his pocket, kissed his wife and family

Went to ride on the M.T.A..

Well, did he ever return? – no, he never returned

And his fate is still unlearned.

He may ride forever ‘neath the streets of Boston.

He’s the man who never returned.

Charlie handed in his dime at the Kendall Square station

And he changed for Jamaica Plain.

When he got there, the conductor told him one more nickel.

Charlie couldn’t get off of that train.”

Titled M.T.A. or Charlie On The M.T.A., a decade later the Kingston Trio defanged it and turned it into a major hit. In recognition in 2004, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority branded the CharlieCard, its equivalent of London’s Oyster Card, after the song’s hero. Call it simplistic thinking but the Oyster Card for its part was probably named for generating pearls for big business, as in rooking Charlies, rather than keeping prices down for commuters. If that’s the way your pleasure tends, M.T.A. and the CharlieCard constitute a small but telling win for the voice of the people and, perhaps, folk music.

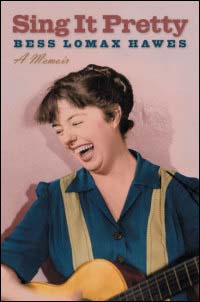

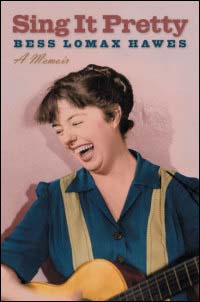

Appropriately, it was the University of Illinois – the same company that had published the biography of her father, Nolan Porterfield’s Last Cavalier – The Life and Times of John A. Lomax (1996) – that published her autobiography, Sing It Pretty: A Memoir (2008). Especially in her later years she bore a hair-raising resemblance to her brother Alan. She was, so to speak, the distaff side of the coin. Doyen of the Smithsonian Institution’s Festival of American Folklife, she became a key figure in the US National Endowment for the Arts before retiring in 1992. In 1993 Bill Clinton felicitated her with the National Medal of the Arts.

Further reading: Sing It Pretty, University of Illinois Press, ISBN: 978-0-252-07509-4 (paperback)

13. 9. 2010 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Scots Gaelic song tradition had a relatively hard time of it during the twentieth century what with a diminishing mother-tongue population, a massive decline in Gaelic literacy and the steady encroachment of Scots and English. Seonag NicCoinnich, that is, Joan MacKenzie in the English, was one of four daughters born into a community where Gaelic was the first language – in Point on the Isle of Lewis in the Western Isles on 2 September 1929.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Scots Gaelic song tradition had a relatively hard time of it during the twentieth century what with a diminishing mother-tongue population, a massive decline in Gaelic literacy and the steady encroachment of Scots and English. Seonag NicCoinnich, that is, Joan MacKenzie in the English, was one of four daughters born into a community where Gaelic was the first language – in Point on the Isle of Lewis in the Western Isles on 2 September 1929.

The spoken and sung language was strong and it was here that she developed her taste and love for Gaelic song. She and her sisters studied in Stornoway where she made her public singing debut as a schoolgirl. She went off to Glasgow to study to become a primary school teacher. She won the traditional singing contest at the Royal National Mod for four consecutive years from 1951. In 1955 she won a Gold Medal at the Mod, presented to her by the Queen Mother with the Queen Elizabeth in attendance.

Her prominence and reputation in Scots Gaelic circles led to her recording for Gaelfonn – she made but two 45s her entire career and they appeared on this small Scottish label – and broadcasting on the BBC’s Scottish service. The School of Scottish Studies at the University of Edinburgh also supplied her with a tape recorder to capture the voices of Lewis for its archives.

Fittingly therefore it was the School of Scottish Studies that oversaw the release of an album of archival recordings. It drew mainly on the School’s recordings with some material from BBC sources and became Joan MacKenzie – Seonag NicCoinnich, volume 19 in the Scottish Tradition Series (Greentrax CDTRAX9019, 1999). It captures her singing between 1955 and 1961 at the height of her powers. Its stand-out performance from 1961 – stand-out for her vocal clarity and control, expressiveness and emotion charge – is the traditional lament Ailein Duinn o hi (‘Dark-haired Alan’ with ‘o hi’ being meaningless vocables). The closing song An till mi tuilleadh a Leodhas? from the BBC archives was composed in exile by a relative on her father’s side – Uilleam MacCoinnich (or William MacKenzie) – whilst living in Ontario where he died in 1908. It translates as ‘Will I ever return to Lewis?’ In 1956 she married Roddy Macleod with whom she had three sons. She died in Edinburgh on 13 May 2007.

30. 8. 2010 |

read more...

« Later articles

Older articles »

[by Ken Hunt, London] British folk music found a top drawer brass player, arranger and composer in Howard Evans. He had an utterly pragmatic, utterly professional attitude to music making and the musician’s life and from 1997, when he joined the Musicians Union’s London headquarters, as assistant general secretary for media he revealed that over and over again. He was totally pragmatic about his art and the first to drolly prick any bubbles of pretension about making music. He brought a wider knowledge and a greater diversity of musical experiences to bear on making music than any professional musician I ever met but he never got the slightest tan from the musical limelight.

[by Ken Hunt, London] British folk music found a top drawer brass player, arranger and composer in Howard Evans. He had an utterly pragmatic, utterly professional attitude to music making and the musician’s life and from 1997, when he joined the Musicians Union’s London headquarters, as assistant general secretary for media he revealed that over and over again. He was totally pragmatic about his art and the first to drolly prick any bubbles of pretension about making music. He brought a wider knowledge and a greater diversity of musical experiences to bear on making music than any professional musician I ever met but he never got the slightest tan from the musical limelight. He mixed years of experience playing brass in military music contexts with the Welsh Guards, in pit orchestras, in London shows such as Cats, Starlight Express and Lou Reizner’s production of The Who’s Tommy and for sessions for the likes of the Star Wars soundtrack, Rick Wakeman, Emerson, Lake & Palmer Evans and the André Previn-era London Symphony Orchestra. Apart from the LSO, he played with the Royal Ballet, Welsh Opera and, most pertinently for his folk connections, with the National Theatre (NT) (as it was called before it got a ‘Royal’ appendage stuck at its front).

He mixed years of experience playing brass in military music contexts with the Welsh Guards, in pit orchestras, in London shows such as Cats, Starlight Express and Lou Reizner’s production of The Who’s Tommy and for sessions for the likes of the Star Wars soundtrack, Rick Wakeman, Emerson, Lake & Palmer Evans and the André Previn-era London Symphony Orchestra. Apart from the LSO, he played with the Royal Ballet, Welsh Opera and, most pertinently for his folk connections, with the National Theatre (NT) (as it was called before it got a ‘Royal’ appendage stuck at its front). That trio grew and in January 1981 metamorphosed into a fresh elemental force eventually called Brass Monkey, an idiom open to various interpretations, as a quintet with Martin Brinsford playing sax, mouthorgan and percussion and Roger Williams trombone, occasionally tuba and euphonium. They stayed together, apart from a period in which Richard Cheetham occupied the trombone chair Williams rejoined. Their head-turning Brass Monkey (1983) (now combined with their second LP See How It Runs (1986) – derived from the Saxa Salt catchphrase – as The Complete Brass Monkey (1993)) contains a remarkable reworking of the incest ballad The Maid And The Palmer, one of the most daring and mesmerising performances ever committed to posterity or perdition. The combination of Evans, Williams and Brinsford playing together will be etched into anyone’s memory who saw them. They were that potent a force. Brass Monkey went on to make five albums with Sound & Rumour (1998), Going & Staying (2001) and Flame of Fire (2004). It was while touring with Brass Monkey that Evans fell ill. He was diagnosed as having cancer. We spoke afterwards and he confessed to an initial rush of ‘Why me?’ thoughts, soon eclipsed, typically, by a ‘Why not me?’ reflection.

That trio grew and in January 1981 metamorphosed into a fresh elemental force eventually called Brass Monkey, an idiom open to various interpretations, as a quintet with Martin Brinsford playing sax, mouthorgan and percussion and Roger Williams trombone, occasionally tuba and euphonium. They stayed together, apart from a period in which Richard Cheetham occupied the trombone chair Williams rejoined. Their head-turning Brass Monkey (1983) (now combined with their second LP See How It Runs (1986) – derived from the Saxa Salt catchphrase – as The Complete Brass Monkey (1993)) contains a remarkable reworking of the incest ballad The Maid And The Palmer, one of the most daring and mesmerising performances ever committed to posterity or perdition. The combination of Evans, Williams and Brinsford playing together will be etched into anyone’s memory who saw them. They were that potent a force. Brass Monkey went on to make five albums with Sound & Rumour (1998), Going & Staying (2001) and Flame of Fire (2004). It was while touring with Brass Monkey that Evans fell ill. He was diagnosed as having cancer. We spoke afterwards and he confessed to an initial rush of ‘Why me?’ thoughts, soon eclipsed, typically, by a ‘Why not me?’ reflection. At the 1982 Cambridge Folk Festival, whilst sitting with the writers Richard Hoare and the John Platt, that West Coast man of many strings David Lindley first heard an act billed as the Martin Carthy Band. A couple of years later, he told me, “It was the most exciting, original thing I’d heard in ten years.” Their proper name was Brass Monkey. Nobody had ever combined voice, stringed and free reed instruments, percussion, reed and brass instruments like Brass Monkey before. Maybe nobody had ever imagined that combination in its blending of folk and wind bands. At Jackson Browne and David Lindley’s Theatre Royal concert in London on 27 March 2006, Lindley called Brass Monkey “one of my favourite bands of all time” and dedicated El Rayo-X to Howard Evans saying “This song is supposed to have horns in it. He’ll be playing.”

At the 1982 Cambridge Folk Festival, whilst sitting with the writers Richard Hoare and the John Platt, that West Coast man of many strings David Lindley first heard an act billed as the Martin Carthy Band. A couple of years later, he told me, “It was the most exciting, original thing I’d heard in ten years.” Their proper name was Brass Monkey. Nobody had ever combined voice, stringed and free reed instruments, percussion, reed and brass instruments like Brass Monkey before. Maybe nobody had ever imagined that combination in its blending of folk and wind bands. At Jackson Browne and David Lindley’s Theatre Royal concert in London on 27 March 2006, Lindley called Brass Monkey “one of my favourite bands of all time” and dedicated El Rayo-X to Howard Evans saying “This song is supposed to have horns in it. He’ll be playing.” [by Ken Hunt, London] Terry Melcher, who died of cancer on 19 November 2004, was a man of many parts and, as Doris Day’s son, doors opened for him. Her only son, he was born Terry Jorden on 8 February 1942. Taking the surname of his mother’s third husband, Martin Melcher (who legally adopted him), he helped shape a generation’s musical consciousness and define the West Coast folk-rock sound. Before that he wrote songs, for instance, with Bobby Darin and Randy Newman, for his mother and for Paul Revere and the Raiders (for whom he penned Him Or Me (What’s It Gonna Be)).

[by Ken Hunt, London] Terry Melcher, who died of cancer on 19 November 2004, was a man of many parts and, as Doris Day’s son, doors opened for him. Her only son, he was born Terry Jorden on 8 February 1942. Taking the surname of his mother’s third husband, Martin Melcher (who legally adopted him), he helped shape a generation’s musical consciousness and define the West Coast folk-rock sound. Before that he wrote songs, for instance, with Bobby Darin and Randy Newman, for his mother and for Paul Revere and the Raiders (for whom he penned Him Or Me (What’s It Gonna Be)). [by Ken Hunt, London] The Bengali singer Suchitra Mitra died on 3 January 2011 at her home of many years, Swastik on Gariahat Road in Ballygunge, Kolkata. She was famed as one of the heavyweight interpreters of the defining Bengali-language song genre form called Rabindra sangeet – or Rabindrasangeet (much like the name Ravi Shankar can also be rendered Ravishankar). ‘Rabindra song’ is an eloquent, literary, light classical song form, derived from the name of the man who ‘invented’ it, Rabindranath Tagore, the winner of the 1913 Nobel Prize for Literature.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Bengali singer Suchitra Mitra died on 3 January 2011 at her home of many years, Swastik on Gariahat Road in Ballygunge, Kolkata. She was famed as one of the heavyweight interpreters of the defining Bengali-language song genre form called Rabindra sangeet – or Rabindrasangeet (much like the name Ravi Shankar can also be rendered Ravishankar). ‘Rabindra song’ is an eloquent, literary, light classical song form, derived from the name of the man who ‘invented’ it, Rabindranath Tagore, the winner of the 1913 Nobel Prize for Literature. [by Ken Hunt, London] Bengal’s popular arts lost two of its major figures on 17 January 2011.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Bengal’s popular arts lost two of its major figures on 17 January 2011. [by Ken Hunt, London] One of my fondest memories of Britain’s specialised music magazine scene of the 1980s into the 1990s is how little ego and rivalry there was for the most part. There were a couple of exceptions (no names, no pack drill) and, strange though it may seem, not a single ornery person from that bunch stayed the course within music criticism. Keith Summers wrote about music, collected it (as in, made field recordings of such as Jumbo Brightwell, the Lings of Blaxhall, Cyril Poacher and Percy Webb as well as later contributing to Topic’s multi-volume series Voice of the People) and published magazines about it. He had the fall-back trade of accountant that funded his passions.

[by Ken Hunt, London] One of my fondest memories of Britain’s specialised music magazine scene of the 1980s into the 1990s is how little ego and rivalry there was for the most part. There were a couple of exceptions (no names, no pack drill) and, strange though it may seem, not a single ornery person from that bunch stayed the course within music criticism. Keith Summers wrote about music, collected it (as in, made field recordings of such as Jumbo Brightwell, the Lings of Blaxhall, Cyril Poacher and Percy Webb as well as later contributing to Topic’s multi-volume series Voice of the People) and published magazines about it. He had the fall-back trade of accountant that funded his passions. [by Ken Hunt, London] The Polish revue artist, singer and actress Irena Anders, born Irena Renata Jarosiewicz on 12 May 1920 in Bruntál, in what is nowadays the Czech Republic, went under the stage name of Renata Bogdańska. Her father was a Rutherian pastor while her mother came from the Polish gentry. She studied music formally at the National Academy of Music in Lviv. The invasion of Poland in September 1939 put paid to her studies and over the next few years the tides of war and the various fortunes of Poland, its citizens and army determined her own life’s course.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Polish revue artist, singer and actress Irena Anders, born Irena Renata Jarosiewicz on 12 May 1920 in Bruntál, in what is nowadays the Czech Republic, went under the stage name of Renata Bogdańska. Her father was a Rutherian pastor while her mother came from the Polish gentry. She studied music formally at the National Academy of Music in Lviv. The invasion of Poland in September 1939 put paid to her studies and over the next few years the tides of war and the various fortunes of Poland, its citizens and army determined her own life’s course. [by Ken Hunt, London] “Ten years ago on a cold dark night/Someone was killed ‘neath the town hall lights./There were few at the scene, but they all did agree/that the man who ran looked a lot like me.”

[by Ken Hunt, London] “Ten years ago on a cold dark night/Someone was killed ‘neath the town hall lights./There were few at the scene, but they all did agree/that the man who ran looked a lot like me.” Long Black Veil (1959) was supposedly nudged into existence by the story of a woman who haunted silent era heartthrob Rudolph Valentino’s graveside. Whether it was a ghostly or a figurative haunting remains the ectoplasm of story repetition, it touched is a sublime piece of haunting. After Leftie Frizzel, a litany of musicians covered including Burl Ives (too regularly marginalised but a major, major influence in folk circles), the Kingston Trio, Joan Baez, Johnny Cash, The Band, the New Riders of the Purple Sage and with The Chieftains with Mick Jagger.

Long Black Veil (1959) was supposedly nudged into existence by the story of a woman who haunted silent era heartthrob Rudolph Valentino’s graveside. Whether it was a ghostly or a figurative haunting remains the ectoplasm of story repetition, it touched is a sublime piece of haunting. After Leftie Frizzel, a litany of musicians covered including Burl Ives (too regularly marginalised but a major, major influence in folk circles), the Kingston Trio, Joan Baez, Johnny Cash, The Band, the New Riders of the Purple Sage and with The Chieftains with Mick Jagger. [by Ken Hunt, London] People’s appreciation of American folk music did not commence with the folk scare of the 1960s and the likes of the Kingston Trio, Peter, Paul and Mary, Joan Baez, Odetta, Buffy Sainte-Marie and Bob Dylan. A generation before them another folk revival, that similarly had no truck with segregation along racial lines, had been under way. Its crop of performers included progressives such as Josh White, Woody Guthrie, Huddie ‘Leadbelly’ Ledbetter and Pete Seeger. Like the next generation, the earlier one wrote new songs in various folk idioms, frequently darts with left-leaning barbs, dosed with class consciousness and social awareness.

[by Ken Hunt, London] People’s appreciation of American folk music did not commence with the folk scare of the 1960s and the likes of the Kingston Trio, Peter, Paul and Mary, Joan Baez, Odetta, Buffy Sainte-Marie and Bob Dylan. A generation before them another folk revival, that similarly had no truck with segregation along racial lines, had been under way. Its crop of performers included progressives such as Josh White, Woody Guthrie, Huddie ‘Leadbelly’ Ledbetter and Pete Seeger. Like the next generation, the earlier one wrote new songs in various folk idioms, frequently darts with left-leaning barbs, dosed with class consciousness and social awareness. [by Ken Hunt, London] The Scots Gaelic song tradition had a relatively hard time of it during the twentieth century what with a diminishing mother-tongue population, a massive decline in Gaelic literacy and the steady encroachment of Scots and English. Seonag NicCoinnich, that is, Joan MacKenzie in the English, was one of four daughters born into a community where Gaelic was the first language – in Point on the Isle of Lewis in the Western Isles on 2 September 1929.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Scots Gaelic song tradition had a relatively hard time of it during the twentieth century what with a diminishing mother-tongue population, a massive decline in Gaelic literacy and the steady encroachment of Scots and English. Seonag NicCoinnich, that is, Joan MacKenzie in the English, was one of four daughters born into a community where Gaelic was the first language – in Point on the Isle of Lewis in the Western Isles on 2 September 1929.