Lives

[by Ken Hunt, London] On 27 February the best-disguised Russian superhero Ivan Rebroff, a singer and star of stage, film, musical and television died. Rebroff kept his origins a closely guarded secret but he had been born Hans-Rolf Rippert in the Spandau district of Berlin on 31 July 1931. He created, to go faux-designer, a huge peasant chic and Cossack bravado that became his trademark for the friendly face of Russia during the Cold War era. It is impossible to estimate what he did for rapprochement during the period. “I brought Russian soul to Germany,” he said once. Controversially and fittingly, Rebroff and the Balalaika Ensemble Troika got to play at the 1967 Burg Waldeck Festival in West Germany – a byword for cultural integrity. Their work, collectively and alone (in the case of the Balalaika Ensemble Troika), appears on the ten-CD boxed set Die Burg Waldeck Festivals 1964-1969 (Bear Family, 2008).

[by Ken Hunt, London] On 27 February the best-disguised Russian superhero Ivan Rebroff, a singer and star of stage, film, musical and television died. Rebroff kept his origins a closely guarded secret but he had been born Hans-Rolf Rippert in the Spandau district of Berlin on 31 July 1931. He created, to go faux-designer, a huge peasant chic and Cossack bravado that became his trademark for the friendly face of Russia during the Cold War era. It is impossible to estimate what he did for rapprochement during the period. “I brought Russian soul to Germany,” he said once. Controversially and fittingly, Rebroff and the Balalaika Ensemble Troika got to play at the 1967 Burg Waldeck Festival in West Germany – a byword for cultural integrity. Their work, collectively and alone (in the case of the Balalaika Ensemble Troika), appears on the ten-CD boxed set Die Burg Waldeck Festivals 1964-1969 (Bear Family, 2008).

Comrade Rebroff’s albums had evocative titles like Kosaken müssen reiten (‘Cossacks Must Ride’) (1970), Na Sdarowje (1968) named after the Russian drinking toast and logically therefore an album to do with alcoholic imbibing, Kalinka (1971) named after the folksong, Meine Reise um die Welt (‘My Journey Around The World’) (2000) and Zwischen Donau und Don (‘Between the Danube and the Don’) (1971) with the Croatian singer Dunja Raijter.

His success was truly international. To give but two examples, he had a best-selling Afrikaans album Ivan Rebroff Sing Vir Ons (‘.Sings For Us’) (1971) and, reflecting his enormous popularity in Australia, the Live In Concert, Sydney – Australia DVD from his sold-out 2004 tour. There is no knowing how many units he shifted but he had 50 or so gold or platinum discs across five continents, starred as Tevye in Un violon sur le toit (as Fiddler On The Roof was called in France) and brought Ah! si j’étais riche (‘If I Were A Rich Man’) to the French public’s notice and he set and broke box-office records everywhere he went. Not bad for a fake Russian superstar.

1. 12. 2008 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The vocalist Mahendra Kapoor, who died at home in Mumbai (Bombay) on 27 September 2008 at the age of 74, has been painted in the outpouring of obituaries at home and abroad as something of a one-trick pony or beast of burden. One claim in the good, old-fashioned Indian way to be taken with a pinch of salt is that he sang some 25,000 songs. Such figures have long since been discredited. While Kapoor was primarily known as a playback singer in Indian film – the vocalists who pre-record songs for actors to ‘sing’, that is mime to – Kapoor’s career reveals that a versatility way beyond playback singing.

28. 10. 2008 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] You could hardly find a more thoroughly Swiss or Swiss-German gentleman than the folk musician Rudolf ‘Ruedi’ Rymann who died on 10 September at his home in Giswil in the Swiss Canton of Obwalden. In the public eye he was a musician and sportsman and by trade he was a farmer and cheese-maker. In retirement he was also a huntsman. He epitomised Swissness.

11. 10. 2008 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Guinean saxophonist and clarinettist, gravely voiced singer and songwriter, Momo ‘Wandel’ Soumah died in his homeland’s capital, Conakry on 16 June 2003. Of Baga tribal stock, he survived the, at times, perilous crossing from colonial times (exemplified by stints in dance bands with names redolent of the period such as La Joviale Symphonie and La Douce Parisette) to independence. During the socialist years of Sékou Touré’s presidency, an Afro-centric sound was de rigueur.

11. 10. 2008 |

read more...

“Here’s to the Ronnie, the voice we adore

“Here’s to the Ronnie, the voice we adore

Like coals from a coal bucket scraping the floor

Sing out his praises in music and malt

And if you’re not Irish, that isn’t your fault” – The Ballad of Ronnie Drew

[by Ken Hunt, London] In November 2006 An Post – Eire’s Post Office – issued a set of four commemorative stamps with portraits of The Clancy Brothers with Tommy Makem, The Dubliners, The Chieftains and Altan on them. Each group added something special to Ireland’s appreciation of its own musical heritage and in turn to the wider world’s appreciation of Irish music. But there was never a folk band to compare to the Dubliners – the Chieftains were quite different – and in his prime Ronnie Drew’s voice was contender for the most distinctive in Irish music.

Born in Dún Laoghaire, Co. Dublin on 16 September 1934, the folk musician, singer and actor Ronnie Drew was a founding member of the Dubliners. Aged 27 he landed back in Dublin after having worked as an English-language teacher in Spain for some years. He fell in with a crowd that hung out at O’Donoghue’s pub in Merrion Row. (O’Donoghue’s features prominently in the annals of Irish folk music, but that is a tale for another time.) A band coalesced, initially under the name of the Ronnie Drew Group. With Joycian reinvention they jettisoned that name – much to Drew’s delight – and assumed a new name based on Luke Kelly’s current reading matter, James Joyce’s 1914 book of short stories, The Dubliners. As a name it sang a sense of regional identity and was both liberating and joyful.

What Ciaran Bourke, Ronnie Drew, Luke Kelly and Barney McKenna created together wasn’t so much a formula as a musical template. Over the next years there would be comings and goings but one of the most important characteristics of the early line-up was the contrasting vocals of Luke Kelly and Ronnie Drew. On their 1964 Transatlantic album (reissued by Wooded Hill Recordings, 1997), Drew’s voice on Love Is Pleasing is like a jackdaw creaking and chuckling across a clear blue morning sky. It was quite different to Kelly’s on Rocky Road To Dublin or Bourke’s on Jar of Porter.

Talking about the Dubliners after Drew’s death, Jenny Barton, who had run the Troubadour club in London’s Earl’s Court district during its 1960s heyday, laughed as she told me, “They weren’t always on time, they weren’t always sober.” But their music was powerful. And there was no band to match them on the British or Irish folk scene.

The Dubliners recorded extensively but one of their defining pieces was the folk novelty hit Seven Drunken Nights. It had once appeared in Francis James Child’s orderly tallying of Anglo-Scottish balladry as Our Goodman. By the time the Dubliners released it, it had been shorn of a couple of nights. It was the heyday of offshore pirate radio – before the Marine Broadcasting Offences Act of 1967 put paid to stations such as Radio Essex, Radio London and Radio Scotland. Radio Caroline just played the 45-rpm single over and over again. Indeed so repeatedly that it was plain that Major Minor – the record company – was ‘subsidising’ their playlist. The Dubliners had shifted to Major Minor after Dominic Behan had effected an introduction. We didn’t know the word payola back then in Europe.

In Eire, RTÉ banned Seven Drunken Nights because of its bawdiness, though the ribaldry was more Carry On… film innuendo and hype than bawdiness per se. Still, as Jane Birkin and Serge Gainsbourg and the Sex Pistols would later learn and demonstrate, banning doesn’t necessarily kill sales. Seven Drunken Nights and Black Velvet Band were both hits in the UK. Drew’s time with the Dubliners was split between two periods: 1962 and 1974 and 1979 and 1995. Interestingly, the Dubliners and the Pogues went on to enjoy a minor hit with The Irish Rover – interesting because there was a sense of camaraderie across the generations with the two groups. Drew collaborated with many people but his collaborations with the ex-De Dannan singer Eleanor Shanley must be mentioned.

In Eire, RTÉ banned Seven Drunken Nights because of its bawdiness, though the ribaldry was more Carry On… film innuendo and hype than bawdiness per se. Still, as Jane Birkin and Serge Gainsbourg and the Sex Pistols would later learn and demonstrate, banning doesn’t necessarily kill sales. Seven Drunken Nights and Black Velvet Band were both hits in the UK. Drew’s time with the Dubliners was split between two periods: 1962 and 1974 and 1979 and 1995. Interestingly, the Dubliners and the Pogues went on to enjoy a minor hit with The Irish Rover – interesting because there was a sense of camaraderie across the generations with the two groups. Drew collaborated with many people but his collaborations with the ex-De Dannan singer Eleanor Shanley must be mentioned.

In addition to making music and mischief, Drew acted in theatre, film, television and revue. He came up with Ronnie I Hardly Knew You – a revue that toured internationally in the 1990s. The revue went to, amongst other places, Scotland, the USA, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Israel. It drew on folksong and the words of Brendan Behan (in whose Richard’s Cork Leg he had acted in the 1970s), Joyce (naturally), Patrick Kavanagh and Sean O’Casey.

In January 2008 members of U2, Kila, the Dubliners and the Band of Bowsies went into Windmill Lane studios in Dublin to record a tribute song to Drew called The Ballad of Ronnie Drew. It was co-authored by the former Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter, U2’s Bono and The Edge and Simon Carmody. ‘Bowsies’ is a Hiberno-English, that is, Irish-English, word connoting a disreputable drunkard or drunken good-for-nothing. Among the people who took on this affectionate moniker were Moya Brennan, Andrea Corr, Shane MacGowan, Christy Moore and Sinéad O’Connor. The song’s profits went to the Irish Cancer Society and it topped the Irish charts. In 2006 Drew had been diagnosed with cancer of the throat.

Ronnie Drew died on Saturday, 16 August 2008, in Dublin, at the age of 73. His obituary appeared the next Monday in The Daily Telegraph, The Guardian, The Independent and The Times in the UK – and that is no mean feat. At his funeral service in Greystones, Co. Wicklow, Phelim Drew came up with a telling anecdote about his father. According to Kathy Sheridan in The Irish Times of 20 August 2008, it concerned Michael Flatley allegedly making a million whatevers a week. “‘What would you do if you earned a million a week?’ Ronnie was asked. ‘I’d work for two. And then I’d stop’, he said.” Well, amen to that. “He was,” laughed Jenny Barton, “a hell of a character” – and on that score nobody could disagree.

Dedicated to Gill Cook (1937-2006)

For information of various sorts about The Ballad of Ronnie Drew, visit http://www.cancer.ie/news/ronnie_drew_song.php and watch the video at http://www.u2.com/highlights/?hid=437

2. 9. 2008 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] At the beginning of the 1960s a new kind of folk scene started to develop in the USA. Overall, the scene consisted very much of localised affairs. In Colorado, Boulder was separate from Denver. The US East Coast scene, notably based around Boston and Cambridge in Massachusetts and New York operated independently of each other. Gradually they made contacts and connections. The dots joined up. Some New York musicians such as David Grisman and Jody Stecher relocated to California, for example. Artie Traum was part of the New York scene but by the late 1960s he was part of the bigger picture.

[by Ken Hunt, London] At the beginning of the 1960s a new kind of folk scene started to develop in the USA. Overall, the scene consisted very much of localised affairs. In Colorado, Boulder was separate from Denver. The US East Coast scene, notably based around Boston and Cambridge in Massachusetts and New York operated independently of each other. Gradually they made contacts and connections. The dots joined up. Some New York musicians such as David Grisman and Jody Stecher relocated to California, for example. Artie Traum was part of the New York scene but by the late 1960s he was part of the bigger picture.

Guitarist, singer-songwriter and composer Arthur Roy Traum was born in New York City on 3 April 1943, younger brother to Happy Traum by five years. Early on, he accompanied the white blues singer Judy Roderick. He made his first recording with the True Endeavor Jug Band – The Art of the Jug Band (Prestige, 1963) – at the beginning of the 1960s. Nevertheless, he made much of his best-known and finest ensemble music with his brother, the Woodstock Mountains Revue (which also included his big brother) and the WMR’s pool of musicians such as Pat Alger (going on to form a partnership with him beginning with their From The Heart (Rounder, 1980). At one point he and his brother co-hosted the WAMC radio show Bring It On Home. The brothers’ names were very much entwined.

During the second half of the 1960s he also took up electric guitar and co-founded a very loud and quite floral rock group, variously, it would appear, known as Bear or the Children of Paradise (though both brothers referred to it only under the latter name in my presence). Co-founded with his brother, the band’s main claim to fame, once the ‘din’ had died down, was that the post-Happy Traum line-up delivered the soundtrack for Greetings. This 1968 film was directed by Brian De Palma – on his way to making Bruce Springsteens’s Dancing In The Dark video (1989) and such films as Bonfire of the Vanities (1990) and Mission: Impossible (1996). Historically speaking though, it was the first film to reach US cinemas in which Robert De Niro appeared in any role beyond that of an extra.

Coevally, a number of musicians coalesced around Woodstock, about 160 km north of New York, amongst them Happy and Artie Traum, Bob Dylan, The Band, Van Morrison and members of Janis Joplin’s Full Tilt Boogie Band (some of whom backed the Traums after her death). Happy moved to Woodstock – not to be confused with the festival of high renown – first in 1967 and Artie moved upstate soon afterwards. In Dick Weissman’s Which Side Are You On? – An Inside History of the Folk Music Revival in America (2005) the author recalls Artie house-sitting “one of the two houses that Bob Dylan owned in Woodstock” and his role as gatekeeper – meaning keeping people at bay so Dylan could maintain, as my father used to say, a modicum of privacy. The Band’s Rick Danko, Levon Helm and Garth Hudson would subsequently join a cadre of musicians that also included Bela Fleck and David Grisman when Artie made his Meetings With Remarkable Musicians (Narada, 1999). Its most poignant track in many ways was his duet Early Frost with his brother, though there is an added element there now since Artie’s death.

Albert Grossman took the two brothers as their manager and they signed with Capitol Records. They recorded two albums for the label – the first being Happy & Artie Traum in 1969 and the second Double-Back in 1971. With Grossman managing them they were positioned to open for a number of major headlining acts – coincidentally also Grossman acts – and appeared at the 1969 Newport Folk Festival. In 1970 Happy Traum who had been helming Sing Out! magazine through one of its finest periods had to relinquish the editorship with the pressure of work and outside commitments. The two brothers’ third album – this time for Rounder – called Hard Times In The Country (1975) was especially fine, with its exploration of Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music and the Pinder Family’s I Bid You Goodnight. It also included three Artie Traum compositions in No Depression Blues, Gambler’s Song and Gold Hill and came with liner notes written by the Beat poet Allen Ginsberg. Ginsberg’s ‘appearance’ was a returned favour of sorts. Like Dylan, Happy had done sessions for a Ginsberg album for the Beatles’ Apple label deemed too uncommercial (Subtitles: risqué) for public consumption – and scatological to boot – though it was eventually released on the Ginsberg collection Holy Soul Jelly Roll (Rhino Word Beat, 1994).

During the early 1970s, Jane Traum prompted her husband Happy one time during an interview with me, the brothers had put on a series of ‘& Friends’ concerts at the Woodstock Playhouse. This led to the formation of the Woodstock Mountains Revue, a loose collective including Pat Alger, Eric Andersen, Paul Butterfield, John Herald, Bill Keith, Maria Muldaur, John Sebastian and Paul Siebel. They made five albums but their finest hour came with the second, More Music From Mud Acres (Rounder, 1977). Artie Traum contributed two marvellous compositions Barbed Wire and Cold Front. (That same year his solo debut Life On Earth appeared on Rounder.) By the late 1970s, a touring band had coalesced. Two further WMR volumes were released in 1990 by the Japanese Village Green label entitled Live at the Bearsville Theater volumes one and two.

Artie had been moved by the music of John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Jim Hall and the Modern Jazz Quartet from early on. Jazz emerged as an important component in his music making. It led eventually to him recording a number of jazz-tinged albums. Letters From Joubee (Shanachie, 1994) contained ten compositions, all written or co-written by Traum, five of them co-credited to Scott Petito (also the album’s producer). Moroccan Wind was an outstanding example of his and Petito’s composing.

Later recordings include The Last Romantic (Narada, 2001), Acoustic Jazz Guitar (Roaring Stream Records, 2004) and Thief of Time (Roaring Stream, 2007). He also created a body of sterling audio/visual education materials, many for his brother’s company Homespun Tapes, amongst them, ones on DADGAD tuning and guitar accompaniment.

He died at his Bearsville, NY home on 20 July 2008.

15. 8. 2008 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Peter Kameron was a man who straddled many fields of the arts and entertainment. He was born in New York City on 18 March 1921 and went on to become the personal manager for a number of US music acts in the 1950s and the 1960s, signally amongst them, the Weavers and the Modern Jazz Quartet.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Peter Kameron was a man who straddled many fields of the arts and entertainment. He was born in New York City on 18 March 1921 and went on to become the personal manager for a number of US music acts in the 1950s and the 1960s, signally amongst them, the Weavers and the Modern Jazz Quartet.

He broadened his approach and built on his expertise and experience to become part of the management team around The Who. They were a rather promising rock group whose Pete Townshend nevertheless made no bones about pitching songs to the folk scene to. (Something forgotten in the accounts.) Kameron was there when The Who set about establishing Track Records (1967-1978), headed by Kit Lambert, Chris Stamp and Pete Townshend. Kameron’s precise role in all this is ill-defined and unclear but he was there. Amongst the acts that recorded for the label were Crazy World of Arthur Brown, The Eire Apparent, Jimi Hendrix, John’s Children (with Marc Bolan) and Thunderclap Newman. It was a label with a vibe. In Polly Marshall’s The God of Hellfire – the Crazy Life and Times of Arthur Brown (2005), she quotes Arthur Brown saying, “We decided on Track, because they did The Who and because Pete was involved.” It was a label with cachet.

Kameron never stayed wholly within music, ducking and diving into independent film-making including You Better Watch Out, film score work and various publishing activities, most notably with the L.A. Weekly. Towards the end of his life, he channeled part of his money into endowing a chair at the UCLA Law School. He died at his home in Beverly Hills, California on 29 June 2008.

The illustration is the cover of Track Records 2406 002 (1970). Even then, the image was odd with its combination of Saskia de Boer’s dolls – the irrelevant presence of DJ John Peel, the Rolling Stone Brian Jones still confuse – and Graphreaks’ concept photographed by Peter Sanders.

19. 7. 2008 |

read more...

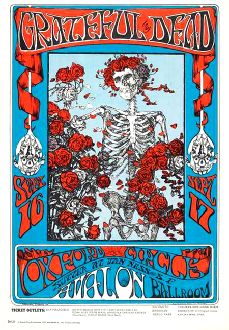

[by Ken Hunt, London] San Francisco’s graphic artist, painter and poster and collage artist, Alton Kelley died at his home in Petaluma, California on 1 June 2008 at the age of 67. It would be hard to over-estimate him as one of San Francisco’s foremost psychedelic artists and his impact on that scene’s rock music in visual and graphic terms. He was central to that blossoming of great handbill, poster and album art that people associate with San Francisco. Kelley blazed happy trails as part of the so-called Great Five – Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, Randy Tuten and Wes Wesley – with the signal difference that while the other four pursued their Muse largely through solitary activities, he shaped his unique vision usually in the glad company of Stanley ‘Mouse’ Miller – though Kelley and Griffin did collaborate on a poster advertising the triple bill of It’s A Beautiful Day, Deep Purple and Cold Blood at the Fillmore Auditorium in 1968.

[by Ken Hunt, London] San Francisco’s graphic artist, painter and poster and collage artist, Alton Kelley died at his home in Petaluma, California on 1 June 2008 at the age of 67. It would be hard to over-estimate him as one of San Francisco’s foremost psychedelic artists and his impact on that scene’s rock music in visual and graphic terms. He was central to that blossoming of great handbill, poster and album art that people associate with San Francisco. Kelley blazed happy trails as part of the so-called Great Five – Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, Randy Tuten and Wes Wesley – with the signal difference that while the other four pursued their Muse largely through solitary activities, he shaped his unique vision usually in the glad company of Stanley ‘Mouse’ Miller – though Kelley and Griffin did collaborate on a poster advertising the triple bill of It’s A Beautiful Day, Deep Purple and Cold Blood at the Fillmore Auditorium in 1968.

Collectively Mouse-Kelley, theirs was a linchpin team that would create Zeitgeist-capturing or timeless images for the San Francisco Bay Area’s finest – the likes of Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Big Brother & The Holding Company and many of the rest. Their images shouted San Francisco to a wider world. The posters and/or album covers that Mouse-Kelley created for Foreigner, Mickey Hart, Robert Hunter, Journey, Led Zeppelin, New Riders of the Purple Sage, the Rolling Stones, Styx and Wings became part of rock iconography. However just as the posters of the Ivančice, Moravian-born artist Alphonse Mucha (1860-1939) are associated with one artist in particular, the ‘divine’ actress Sarah Bernhard (1844-1923), so Mouse-Kelley came to be associated in particular with the Grateful Dead (1965-1995).

Kelley had headed west like so many others before him. The poetry talks of running out of road, braking before hitting the waters of the Pacific. But the reality had been crueller for generations. He settled in San Francisco in the mid 1960s. His actual birthplace was Houlton, Maine, where he was born on 17 June 1940. He did his proper growing up in Stratford and Bridgeport, Connecticut. Cars became a big deal and while still attending high school he fell under their automotive spell in the grand American way. As he would do till the end of his years, he would channel his obsession for cars into his artwork. He would do bespoke hot-rod-style paint jobs on them, he would showcase their images on posters and T-shirts, and he embraced the mythology of cars wholeheartedly, as much as his fellow Americans Hank Williams, Chuck Berry, Commander Cody & His Lost Planet Airmen and Bruce Springsteen did. It was the American car ‘n’ lost highway tradition in pictures. Plus and next, it was hardly coincidence that his longstanding collaborator, Mouse was similarly hooked on automotive excess, imagery and symbolism. That stuff calls and beckons down the tenses.

Kelley had headed west like so many others before him. The poetry talks of running out of road, braking before hitting the waters of the Pacific. But the reality had been crueller for generations. He settled in San Francisco in the mid 1960s. His actual birthplace was Houlton, Maine, where he was born on 17 June 1940. He did his proper growing up in Stratford and Bridgeport, Connecticut. Cars became a big deal and while still attending high school he fell under their automotive spell in the grand American way. As he would do till the end of his years, he would channel his obsession for cars into his artwork. He would do bespoke hot-rod-style paint jobs on them, he would showcase their images on posters and T-shirts, and he embraced the mythology of cars wholeheartedly, as much as his fellow Americans Hank Williams, Chuck Berry, Commander Cody & His Lost Planet Airmen and Bruce Springsteen did. It was the American car ‘n’ lost highway tradition in pictures. Plus and next, it was hardly coincidence that his longstanding collaborator, Mouse was similarly hooked on automotive excess, imagery and symbolism. That stuff calls and beckons down the tenses.

Kelley came out of an industrial design background. While he was never an academic, he knew his art and what moved him. He was a working-class pragmatist who had spent much of his life not in art adventures but in working as a mechanic and/or welder working on helicopters or road vehicles. He reached California in the 1960s, first settling in Los Angeles before relocating in San Francisco. His move coincided with San Francisco’s psychedelic explosion. Kelley was not especially precise about when he arrived in San Francisco, but his timing, whenever it was, was impeccable. The Vietnam War was in full spate and he needed something alternative in art terms. As he is quoted as saying in Mouse & Kelley (Paper Tiger, 1979), “Cars seemed as glamorous as washing machines.” He was being cute. He had bought into cars’ sleek-lined, finned and fendered iconography. He and Mouse would return to automotive imagery over and over again.

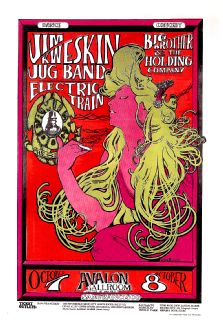

In 1965 he became a member of San Francisco’s hippie collective going under the name of the Family Dog. Amongst its number were Luria Castell, Chet Helms, Ellen Harmon and Jack Towle. And the collective had this bizarre notion to put on dance-concerts. Around 1965 the San Francisco Bay Area was becoming very different from elsewhere in the States. For one thing it was – and is – a walking city. Using public transport still carries no connotations of poverty, as elsewhere in citified USA. People walked or hopped on a trolley or a streetcar. And then continued walking. Haight’s telegraph poles were covered with theatre and concert posters. And, just like today, they had adverts of all sorts tacked to them. Only these posters and handbills tugged at the eyeballs in a new way. These were advertising the next Grateful Dead, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Big Brother or Jefferson Airplane gig. And if it was a Family Dog dance-concert poster, it was advertising the next the Avalon Ballroom show on Sutter.

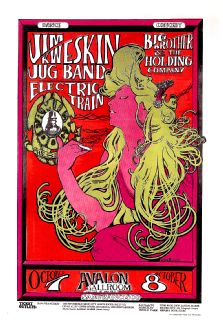

Kelley had the great, good fortune to bump into Mouse around this time. Mouse, born in Fresno, California on 10 October 1940, was likewise predisposed to the counterculture values of this new San Franciscan scene and the pictorial and graphic wonders of the past. They forged a new creative partnership. The partnership worked its influences relentlessly. Their posters were a hit-and-run artistic service. On their Howlin’ Wolf and Big Brother & The Holding Company poster at the Avalon in 1966 a slavering wolf roared. For the Dead and Sopwith Camel’s gig there that same year Frankenstein gazed out. The Mount Tamalpais Outdoor Theater gig with Joan Baez, Mimi Farina, the Grateful Dead and Quicksilver Messenger Service had Winnie The Pooh and his winsome little sidekick heading into the sunset, probably past the Sunset end of San Francisco, left of Golden Gate Park in other words, and onwards to the Pacific.

Kelley had the great, good fortune to bump into Mouse around this time. Mouse, born in Fresno, California on 10 October 1940, was likewise predisposed to the counterculture values of this new San Franciscan scene and the pictorial and graphic wonders of the past. They forged a new creative partnership. The partnership worked its influences relentlessly. Their posters were a hit-and-run artistic service. On their Howlin’ Wolf and Big Brother & The Holding Company poster at the Avalon in 1966 a slavering wolf roared. For the Dead and Sopwith Camel’s gig there that same year Frankenstein gazed out. The Mount Tamalpais Outdoor Theater gig with Joan Baez, Mimi Farina, the Grateful Dead and Quicksilver Messenger Service had Winnie The Pooh and his winsome little sidekick heading into the sunset, probably past the Sunset end of San Francisco, left of Golden Gate Park in other words, and onwards to the Pacific.

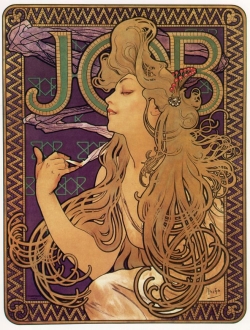

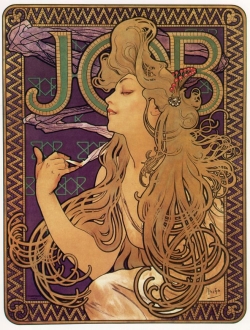

The Mouse-Kelley team proved as eclectic as the musicians themselves in their thieving. (The San Francisco Bay Area musicians stole beautifully.) What was grist to their mill? Well, old advertisements and mail order catalogues, images of Hollywood and Native Americans, science-fiction extraterrestrials and UFOs, sweet wrappers and robot visages, G-L-O-R-I-A Swanson and Mad magazine’s mascot-in-chief Alfred E. ‘What me worry?’ Neuman all figured. But from early on they snaffled the sensibilities of Belle Époque, Art Deco and Jugendstil materials. And since we are a Prague-based website, let’s be unambiguous: Alphonse Mucha must be mentioned. They gave Ol’ Mucha a new twist of psychedelicised life. ‘Girl with Green Hair’ advertised a 1966 Avalon Ballroom dance-concert by the Jim Kweskin Jug Band and Big Brother & The Holding Company. Out of the kindness of their hearts, an attractive woman whose original job in life was to sell Job cigarette papers was re-employed.

Poster art has an illustrious history but it is predominantly a commercial art. Just as Mucha had his champagne and Job cigarette papers, Kelley-Mouse had their images of hot rods and, er, Zig-zag cigarette papers. Theirs was definitely commercial art. Their 1973 Monster T-Shirt Catalog peddled clothing with images of bygone babes, dragsters, a jester holding a skull mask or stroking his chin, cosmic goofs and even rolling papers.

Poster art has an illustrious history but it is predominantly a commercial art. Just as Mucha had his champagne and Job cigarette papers, Kelley-Mouse had their images of hot rods and, er, Zig-zag cigarette papers. Theirs was definitely commercial art. Their 1973 Monster T-Shirt Catalog peddled clothing with images of bygone babes, dragsters, a jester holding a skull mask or stroking his chin, cosmic goofs and even rolling papers.

By 1966 they were branching out into album cover art with the Grateful Dead’s eponymous debut. It is a period piece, a journeyman collage without any of the flair of their later work but this was an era of scalpel and cow gum. It is drab beside their later silkscreen poster work or their plunging into Pantone’s new fluorescent colours territory.

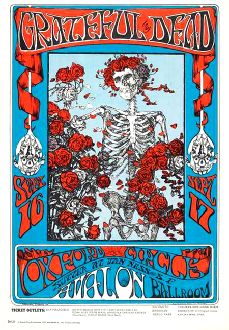

The Mouse-Kelley team came to work extensively with the Dead, indeed went on the payroll as part of the band’s extended family, it was said. They contributed massively to the Dead’s image. Kelley’s adaptation of an Edmund Sullivan illustration in the 1859 edition of Edward Fitzgerald’s The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám was perhaps their most iconic contribution. If it had been a film it would have blazed like the icons in Andrei Rublev, Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1966 film. It depicted a skeleton with a skull crowned or wreathed – choose your symbology – with roses. It started as a 1966 concert image, became an album cover in 1971 (for, confusingly, another Grateful Dead, this time a double live album) and afterwards entered the Dead’s core iconography.

They would work with other Dead images. The dusty brown cover photograph of Workingman’s Dead (1970) was Kelley wiping the lens on his Brownie camera. American Beauty (1970) employed rose symbolism – American Beauty is a variety of rose – and the ambiguity of lettering (‘American Reality’ could also be read). The triple-LP Europe ‘72 (1972) went cartoon on its cover. Terrapin Station (1975) included a sly reference to a Fillmore Auditorium poster for a Turtles (and Oxford Circle) gig that Heinrich Kley and Wes Wilson had done in 1966. That was the thing about Alton Kelley. If you knew your art and music history, there was so much in those images to nod sagely in agreement to. But there was a lot more in the way of allusions that you knew you would have to crack later. That is the history and magic of art, with or without the oomph of psychotropic substances.

We thank the copyright holders for permission to use:

Girl with Green Hair (c) Mouse/Kelley 1966 for FD, Rhino Entertainment

Skeleton and roses image (c) Mouse/Kelley 1966 for FD, Rhino Entertainment

Grateful Dead logo (c) Mouse/Kelley

14. 6. 2008 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Kirana gharana – or school of playing – seated in Kirana, near Saharanpur in India’s state of Uttar Pradesh, is one of the major styles of performance in Hindustani music. Kirana is particularly noted for the quality of its vocalists. Historically, it was associated with great maestros such as Abdul Karim Khan and Sawai Gandharva. In more recent times it was associated with singers who carried the torch on such as Bhimsen Joshi…

12. 5. 2008 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Like Ron Edwards (1930-2008), the Australian folklorist and folk recordist, folk journalist and archivist Edgar Waters was a pioneer in the field of Australian folksong and folklore. In 1947 he co-authored Rebel Songs with Stephen Murray-Smith, a booklet for the A.S.L.F. – a slim volume similar to the Workers’ Music Association booklets that were being published in Britain.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Like Ron Edwards (1930-2008), the Australian folklorist and folk recordist, folk journalist and archivist Edgar Waters was a pioneer in the field of Australian folksong and folklore. In 1947 he co-authored Rebel Songs with Stephen Murray-Smith, a booklet for the A.S.L.F. – a slim volume similar to the Workers’ Music Association booklets that were being published in Britain.

Waters was working in Britain by the mid 1950s and assisted Alan Lomax on his Folk Songs of North America (1960) before returning to Australia. It was an era of small specialist record companies worldwide, many of which operated on a shoestring. Australia’s version of, say, Topic Records in Britain, was the Sydney, NSW-based Wattle company (1955-1963). Waters fell in with Wattle’s founder Peter Hamilton. They worked together on influential early volumes in Wattle’s so-called Archive Series such as Australian Traditional Singers (1957) and Australian Traditional Singers and Musicians of Victoria (1960), which brought the likes of Catherine Peatey, Sally Sloane and Duke Tritton to people’s attention.

These were the early days of Australian Folk Revival and he had a hand in bringing the likes of the Buckwhackers, the English folklorists and singer A.L. Lloyd, the Rambleers and, in 1963, the Aboriginal singer-songwriter Dougie Young to the public’s attention. Later Waters was a key figure in the documentation of this scene and movement, working with the National Library of Australia and its Oral History and Folklore sections. Waters’ writings on folk and jazz graced many LP and CD releases, The Australian and The Oxford Companion to Australian Folklore (1993).

Edgar Waters died on 1 May 2008.

Note:

This piece was corrected on 8 July 2014. Thanks go to Alistair Banfield for alerting the author to a mistaken spelling. Alistair wrote, “The group that Edgar Waters was involved with was called the ‘Bushwhackers’ not the ‘Bushwackers’ – who were a later Australian group or Buckwackers as you have it.”

For more information and images visit, “Wattle Records and Films” at http://www.abc.net.au/rn/history/hindsight/stories/s1157792.htm

For more information about Ron Edwards on this site visit, http://kenhunt.doruzka.com/index.php/ron-edwards-1930-2008/

Additionally, Dave Arthur’s Bert Lloyd – The Life and Times of A.L. Lloyd (2012) contains further illuminations about Edgar and Ann Waters’ time and work in Britain in the early 1950s.

�

8. 5. 2008 |

read more...

« Later articles

Older articles »

[by Ken Hunt, London] On 27 February the best-disguised Russian superhero Ivan Rebroff, a singer and star of stage, film, musical and television died. Rebroff kept his origins a closely guarded secret but he had been born Hans-Rolf Rippert in the Spandau district of Berlin on 31 July 1931. He created, to go faux-designer, a huge peasant chic and Cossack bravado that became his trademark for the friendly face of Russia during the Cold War era. It is impossible to estimate what he did for rapprochement during the period. “I brought Russian soul to Germany,” he said once. Controversially and fittingly, Rebroff and the Balalaika Ensemble Troika got to play at the 1967 Burg Waldeck Festival in West Germany – a byword for cultural integrity. Their work, collectively and alone (in the case of the Balalaika Ensemble Troika), appears on the ten-CD boxed set Die Burg Waldeck Festivals 1964-1969 (Bear Family, 2008).

[by Ken Hunt, London] On 27 February the best-disguised Russian superhero Ivan Rebroff, a singer and star of stage, film, musical and television died. Rebroff kept his origins a closely guarded secret but he had been born Hans-Rolf Rippert in the Spandau district of Berlin on 31 July 1931. He created, to go faux-designer, a huge peasant chic and Cossack bravado that became his trademark for the friendly face of Russia during the Cold War era. It is impossible to estimate what he did for rapprochement during the period. “I brought Russian soul to Germany,” he said once. Controversially and fittingly, Rebroff and the Balalaika Ensemble Troika got to play at the 1967 Burg Waldeck Festival in West Germany – a byword for cultural integrity. Their work, collectively and alone (in the case of the Balalaika Ensemble Troika), appears on the ten-CD boxed set Die Burg Waldeck Festivals 1964-1969 (Bear Family, 2008). “Here’s to the Ronnie, the voice we adore

“Here’s to the Ronnie, the voice we adore In Eire, RTÉ banned Seven Drunken Nights because of its bawdiness, though the ribaldry was more Carry On… film innuendo and hype than bawdiness per se. Still, as Jane Birkin and Serge Gainsbourg and the Sex Pistols would later learn and demonstrate, banning doesn’t necessarily kill sales. Seven Drunken Nights and Black Velvet Band were both hits in the UK. Drew’s time with the Dubliners was split between two periods: 1962 and 1974 and 1979 and 1995. Interestingly, the Dubliners and the Pogues went on to enjoy a minor hit with The Irish Rover – interesting because there was a sense of camaraderie across the generations with the two groups. Drew collaborated with many people but his collaborations with the ex-De Dannan singer Eleanor Shanley must be mentioned.

In Eire, RTÉ banned Seven Drunken Nights because of its bawdiness, though the ribaldry was more Carry On… film innuendo and hype than bawdiness per se. Still, as Jane Birkin and Serge Gainsbourg and the Sex Pistols would later learn and demonstrate, banning doesn’t necessarily kill sales. Seven Drunken Nights and Black Velvet Band were both hits in the UK. Drew’s time with the Dubliners was split between two periods: 1962 and 1974 and 1979 and 1995. Interestingly, the Dubliners and the Pogues went on to enjoy a minor hit with The Irish Rover – interesting because there was a sense of camaraderie across the generations with the two groups. Drew collaborated with many people but his collaborations with the ex-De Dannan singer Eleanor Shanley must be mentioned. [by Ken Hunt, London] At the beginning of the 1960s a new kind of folk scene started to develop in the USA. Overall, the scene consisted very much of localised affairs. In Colorado, Boulder was separate from Denver. The US East Coast scene, notably based around Boston and Cambridge in Massachusetts and New York operated independently of each other. Gradually they made contacts and connections. The dots joined up. Some New York musicians such as David Grisman and Jody Stecher relocated to California, for example. Artie Traum was part of the New York scene but by the late 1960s he was part of the bigger picture.

[by Ken Hunt, London] At the beginning of the 1960s a new kind of folk scene started to develop in the USA. Overall, the scene consisted very much of localised affairs. In Colorado, Boulder was separate from Denver. The US East Coast scene, notably based around Boston and Cambridge in Massachusetts and New York operated independently of each other. Gradually they made contacts and connections. The dots joined up. Some New York musicians such as David Grisman and Jody Stecher relocated to California, for example. Artie Traum was part of the New York scene but by the late 1960s he was part of the bigger picture. [by Ken Hunt, London] Peter Kameron was a man who straddled many fields of the arts and entertainment. He was born in New York City on 18 March 1921 and went on to become the personal manager for a number of US music acts in the 1950s and the 1960s, signally amongst them, the Weavers and the Modern Jazz Quartet.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Peter Kameron was a man who straddled many fields of the arts and entertainment. He was born in New York City on 18 March 1921 and went on to become the personal manager for a number of US music acts in the 1950s and the 1960s, signally amongst them, the Weavers and the Modern Jazz Quartet. [by Ken Hunt, London] San Francisco’s graphic artist, painter and poster and collage artist, Alton Kelley died at his home in Petaluma, California on 1 June 2008 at the age of 67. It would be hard to over-estimate him as one of San Francisco’s foremost psychedelic artists and his impact on that scene’s rock music in visual and graphic terms. He was central to that blossoming of great handbill, poster and album art that people associate with San Francisco. Kelley blazed happy trails as part of the so-called Great Five – Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, Randy Tuten and Wes Wesley – with the signal difference that while the other four pursued their Muse largely through solitary activities, he shaped his unique vision usually in the glad company of Stanley ‘Mouse’ Miller – though Kelley and Griffin did collaborate on a poster advertising the triple bill of It’s A Beautiful Day, Deep Purple and Cold Blood at the Fillmore Auditorium in 1968.

[by Ken Hunt, London] San Francisco’s graphic artist, painter and poster and collage artist, Alton Kelley died at his home in Petaluma, California on 1 June 2008 at the age of 67. It would be hard to over-estimate him as one of San Francisco’s foremost psychedelic artists and his impact on that scene’s rock music in visual and graphic terms. He was central to that blossoming of great handbill, poster and album art that people associate with San Francisco. Kelley blazed happy trails as part of the so-called Great Five – Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, Randy Tuten and Wes Wesley – with the signal difference that while the other four pursued their Muse largely through solitary activities, he shaped his unique vision usually in the glad company of Stanley ‘Mouse’ Miller – though Kelley and Griffin did collaborate on a poster advertising the triple bill of It’s A Beautiful Day, Deep Purple and Cold Blood at the Fillmore Auditorium in 1968. Kelley had headed west like so many others before him. The poetry talks of running out of road, braking before hitting the waters of the Pacific. But the reality had been crueller for generations. He settled in San Francisco in the mid 1960s. His actual birthplace was Houlton, Maine, where he was born on 17 June 1940. He did his proper growing up in Stratford and Bridgeport, Connecticut. Cars became a big deal and while still attending high school he fell under their automotive spell in the grand American way. As he would do till the end of his years, he would channel his obsession for cars into his artwork. He would do bespoke hot-rod-style paint jobs on them, he would showcase their images on posters and T-shirts, and he embraced the mythology of cars wholeheartedly, as much as his fellow Americans Hank Williams, Chuck Berry, Commander Cody & His Lost Planet Airmen and Bruce Springsteen did. It was the American car ‘n’ lost highway tradition in pictures. Plus and next, it was hardly coincidence that his longstanding collaborator, Mouse was similarly hooked on automotive excess, imagery and symbolism. That stuff calls and beckons down the tenses.

Kelley had headed west like so many others before him. The poetry talks of running out of road, braking before hitting the waters of the Pacific. But the reality had been crueller for generations. He settled in San Francisco in the mid 1960s. His actual birthplace was Houlton, Maine, where he was born on 17 June 1940. He did his proper growing up in Stratford and Bridgeport, Connecticut. Cars became a big deal and while still attending high school he fell under their automotive spell in the grand American way. As he would do till the end of his years, he would channel his obsession for cars into his artwork. He would do bespoke hot-rod-style paint jobs on them, he would showcase their images on posters and T-shirts, and he embraced the mythology of cars wholeheartedly, as much as his fellow Americans Hank Williams, Chuck Berry, Commander Cody & His Lost Planet Airmen and Bruce Springsteen did. It was the American car ‘n’ lost highway tradition in pictures. Plus and next, it was hardly coincidence that his longstanding collaborator, Mouse was similarly hooked on automotive excess, imagery and symbolism. That stuff calls and beckons down the tenses. Kelley had the great, good fortune to bump into Mouse around this time. Mouse, born in Fresno, California on 10 October 1940, was likewise predisposed to the counterculture values of this new San Franciscan scene and the pictorial and graphic wonders of the past. They forged a new creative partnership. The partnership worked its influences relentlessly. Their posters were a hit-and-run artistic service. On their Howlin’ Wolf and Big Brother & The Holding Company poster at the Avalon in 1966 a slavering wolf roared. For the Dead and Sopwith Camel’s gig there that same year Frankenstein gazed out. The Mount Tamalpais Outdoor Theater gig with Joan Baez, Mimi Farina, the Grateful Dead and Quicksilver Messenger Service had Winnie The Pooh and his winsome little sidekick heading into the sunset, probably past the Sunset end of San Francisco, left of Golden Gate Park in other words, and onwards to the Pacific.

Kelley had the great, good fortune to bump into Mouse around this time. Mouse, born in Fresno, California on 10 October 1940, was likewise predisposed to the counterculture values of this new San Franciscan scene and the pictorial and graphic wonders of the past. They forged a new creative partnership. The partnership worked its influences relentlessly. Their posters were a hit-and-run artistic service. On their Howlin’ Wolf and Big Brother & The Holding Company poster at the Avalon in 1966 a slavering wolf roared. For the Dead and Sopwith Camel’s gig there that same year Frankenstein gazed out. The Mount Tamalpais Outdoor Theater gig with Joan Baez, Mimi Farina, the Grateful Dead and Quicksilver Messenger Service had Winnie The Pooh and his winsome little sidekick heading into the sunset, probably past the Sunset end of San Francisco, left of Golden Gate Park in other words, and onwards to the Pacific. Poster art has an illustrious history but it is predominantly a commercial art. Just as Mucha had his champagne and Job cigarette papers, Kelley-Mouse had their images of hot rods and, er, Zig-zag cigarette papers. Theirs was definitely commercial art. Their 1973 Monster T-Shirt Catalog peddled clothing with images of bygone babes, dragsters, a jester holding a skull mask or stroking his chin, cosmic goofs and even rolling papers.

Poster art has an illustrious history but it is predominantly a commercial art. Just as Mucha had his champagne and Job cigarette papers, Kelley-Mouse had their images of hot rods and, er, Zig-zag cigarette papers. Theirs was definitely commercial art. Their 1973 Monster T-Shirt Catalog peddled clothing with images of bygone babes, dragsters, a jester holding a skull mask or stroking his chin, cosmic goofs and even rolling papers. [by Ken Hunt, London] Like Ron Edwards (1930-2008), the Australian folklorist and folk recordist, folk journalist and archivist Edgar Waters was a pioneer in the field of Australian folksong and folklore. In 1947 he co-authored Rebel Songs with Stephen Murray-Smith, a booklet for the A.S.L.F. – a slim volume similar to the Workers’ Music Association booklets that were being published in Britain.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Like Ron Edwards (1930-2008), the Australian folklorist and folk recordist, folk journalist and archivist Edgar Waters was a pioneer in the field of Australian folksong and folklore. In 1947 he co-authored Rebel Songs with Stephen Murray-Smith, a booklet for the A.S.L.F. – a slim volume similar to the Workers’ Music Association booklets that were being published in Britain.