Lives

[by Ken Hunt, London] The sitarist, composer and teacher Shashi Mohan Bhatt began what might be called a family tradition: that of taking Pandit Ravi Shankar as their guru. His son Krishna Mohan Bhatt and his sister Manju Mehta (her married name) – both of whom played sitar – and his younger brother Vishwa Mohan Bhatt – who played a modified acoustic guitar he named Mohan vina player – would all go on to study with the sitar maestro Ravi Shankar. Shashi Mohan Bhatt, however, was one of Shankar’s first shishyas (pupil-disciples). Nobody was quite sure, least of all Ravi Shankar, but Shashi Mohan Bhatt was definitely one of the first three.

4. 5. 2008 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] On 15 April 2008 Mahinarangi Tocker, the Maori musician, songwriter, feminist, gay and lesbian rights activist and political campaigner, died in Auckland, New Zealand. She was one of New Zealand’s most conspicuous song-makers and bore comparison with Joan Armatrading and Tracy Chapman. Born in 1956, she was of mixed bloodlines. She was of Ngati Maniapoto, Ngati Raukawa and Ngati Tuwharetoa – Ngati is a Maori tribal prefix -, Jewish and European stock, hence the title of one of her albums…

19. 4. 2008 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Ola Brunkert is probably the strongest contender for the drummer you’ve heard the most whose name you don’t know. The Swedish drummer played on nearly every Abba recording from 1972 to their dissolution in 1982. Born in Örebro in Sweden on 15 September 1946, Brunkert’s musical background was primarily blues and jazz.

2. 4. 2008 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Jamaican musician, record producer, DJ and broadcaster died 15 March 2008. Especially during the 1980s he bridged the gap between reggae and punk, notably through his work with The Clash on their 1980 Bankrobber single, the US album Black Market Clash (1980) and their marvellously sprawling, spiky and self-indulgent Sandinista! (1989)

2. 4. 2008 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The folklorist, folk and ethnic music collector, author, radio broadcaster and producer Henrietta Yurchenco died in Manhattan on 10 December 2007 at the age of 91. She was one of the great links between the racially integrated and progressive-minded US folk scene of the 1930s and 1940s and the folk boom of the 1950s and 1960s, Over the course of her long life in music – the title of her autobiography Around the World in 80 Years (2003) was apt – she was a shaping influence in what people understood by folk music and a kingpin of ethnomusicology and world music.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The folklorist, folk and ethnic music collector, author, radio broadcaster and producer Henrietta Yurchenco died in Manhattan on 10 December 2007 at the age of 91. She was one of the great links between the racially integrated and progressive-minded US folk scene of the 1930s and 1940s and the folk boom of the 1950s and 1960s, Over the course of her long life in music – the title of her autobiography Around the World in 80 Years (2003) was apt – she was a shaping influence in what people understood by folk music and a kingpin of ethnomusicology and world music.

Born Henrietta Weiss in New Haven, Connecticut on 22 March 1916, her parents – Yitzak (Edward) and Rebecca Weiss – were immigrants from the Ukraine. Both of them sang and her father played mandolin, so there was music in her genes. Growing up during the Depression politicized her. At the Yale School of Music she studied piano and seemed set to pursue a career as a concert pianist. She met her husband-to-be Boris Yurchenco at a John Reed Club meeting. (The John Reed Club was an association named after the author of the book Ten Days That Shook The World (1920) about Lenin and the Bolshevik Revolution.) Boris Yurchenco, an Argentine-born painter, was a kindred spirit politically. The year they married – 1936 – the Yurchencos left New Haven for New York, her base of operations for most of her life. Before they left New Haven she was arrested for demonstrating against an Italian brass band with connections to the Mussolini-era fascist dictatorship. It would be the first of many occasions when protesting got her arrested.

In New York City the Yurchencos hooked up and mingled with people in the arts and of similar political persuasions. One thing that happened soon after arriving in NYC was her decision to opt for a post with station WNYC rather than follow a classical piano future (though she continued to play piano for the rest of her life). At WNYC rather than become one of the ‘backroom boys’ or an anonymous continuity voice, she became a name broadcaster. She presented Adventures in Music, a show dedicated to broadcasting the likes of the Almanac Singers, Woody Guthrie, Aunt Mollie Jackson, Huddie ‘Leadbelly’ Ledbetter, Pete Seeger and Josh White. “All of them,” she recalled, “with the exception of Leadbelly, were politically conscious.” Leadbelly was no doubt shrewd enough to keep what politics he had to himself. He certainly had cause enough in a, politically speaking, carcinogenetic era.

In New York City the Yurchencos hooked up and mingled with people in the arts and of similar political persuasions. One thing that happened soon after arriving in NYC was her decision to opt for a post with station WNYC rather than follow a classical piano future (though she continued to play piano for the rest of her life). At WNYC rather than become one of the ‘backroom boys’ or an anonymous continuity voice, she became a name broadcaster. She presented Adventures in Music, a show dedicated to broadcasting the likes of the Almanac Singers, Woody Guthrie, Aunt Mollie Jackson, Huddie ‘Leadbelly’ Ledbetter, Pete Seeger and Josh White. “All of them,” she recalled, “with the exception of Leadbelly, were politically conscious.” Leadbelly was no doubt shrewd enough to keep what politics he had to himself. He certainly had cause enough in a, politically speaking, carcinogenetic era.

Generally these folksingers performed live over the airwaves and, given the nature of such things, that music existed only for that moment and in listeners’ memories. Once transmitted, that was that. We can perhaps get a little of the flavour of how Yurchenco’s programmes might have sounded from one non-WNYC set that did survive. Woody and Marjorie Guthrie’s The Live Wire, a wire recording from Newark, New Jersey in 1949 eventually released commercially in 2007, bottles the Zeitgeist. It captures Guthrie’s spontaneity as he sings and adlibs into the microphone with a naturalness generally lacking in his commercial recordings. Its Tom Joad, 1913 Massacre and Talking Dust Bowl Blues recall songs in the firm flush of their youth, still malleable, not like frozen moments on a record. During the autumn of 1940 WNYC, with Yurchenco in the producer’s chair, began running Leadbelly’s own unscripted radio show Folksongs of America. “Everything was improvised. Each song was preceded by stories of his life in the South,” she recalls in Charles Wolfe and Kip Lornell’s The Life and Legend of Leadbelly (1993). “We went on live, and whatever happened during that fifteen minutes happened.”

In NYC the Yurchencos’ circle of friends and acquaintances wasn’t restricted to folksingers. It grew to include the composers Béla Bartók (“one of the pioneers of folk music research,” as she describes him in her autobiography) and Aaron Copland, the painter Frida Kahlo, the conductor Otto Klemperer and the Chilean writer Pablo Neruda. Nevertheless, she was in a unique position and uniquely placed to champion the rise of folk music in the city. Just as she championed the generation of Guthrie, Leadbelly and Pete Seeger, a generation on she would later encourage the likes of Bob Dylan and Janis Ian. She straddled the generation gap.

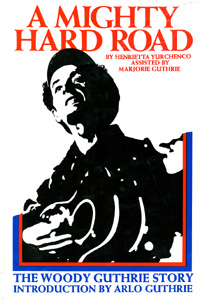

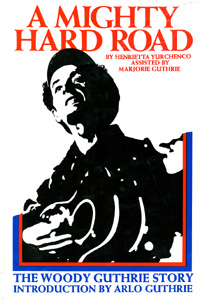

Her 1970 book A Mighty Hard Road, an important addition to the folk music literature, would be Guthrie’s first major biography. (“When I was writing my biography of Woody Guthrie [.] I asked permission to use [Dylan’s] Song To Woody featured on his first album,” she wrote. “It took six months before I received an answer. He granted permission, but only after reading my manuscript.”) Her perspective and experience meant she became an important participant in the historical discourse. She and Pete Seeger are to be seen on film, for example, reminiscing about the folksinger and folk music collector Alan Lomax in Rogier Kappers’s superb documentary Lomax: The Songhunter (2005).

Her 1970 book A Mighty Hard Road, an important addition to the folk music literature, would be Guthrie’s first major biography. (“When I was writing my biography of Woody Guthrie [.] I asked permission to use [Dylan’s] Song To Woody featured on his first album,” she wrote. “It took six months before I received an answer. He granted permission, but only after reading my manuscript.”) Her perspective and experience meant she became an important participant in the historical discourse. She and Pete Seeger are to be seen on film, for example, reminiscing about the folksinger and folk music collector Alan Lomax in Rogier Kappers’s superb documentary Lomax: The Songhunter (2005).

US folk music, it turned out, was but one primary colour on her palette. She took her first steps into the ethnographical wilderness at the age of 21. It ushered in the next important chapter in her life. The Yurchencos lugged their state-of-art portable recording equipment – some 400-600 kg of Presto K recorder, aluminium and steel acetate discs, batteries and so on – to places in Mexico where tribal peoples were cut off from mainstream Mexican society by geography, topography and time, where radio did not reach. Her 1942-1946 Mexican and Guatemalan field recordings from Mexico and Guatemala saw commercial release on the Library of Congress’ Folk Music of Mexico (1948) and Indian Music of Mexico (1952), though Folkways’ front cover artwork had the credit ‘Urchenco’. She returned to Folkways only in 1968 with her Latin American Children’s Game Songs Recorded in Puerto Rico and Mexico. (The hiatus had nothing to do any spelling mistake.) In the meanwhile, Nonesuch Explorer had released The Real Mexico (1966), her best-known and most commercially successful album. Yurchenco’s peyote ritual recordings predate the better-known ones captured by Harry Smith, the acclaimed oddball compiler of the Anthology of American Folk Music.

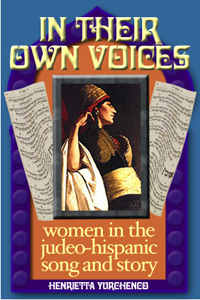

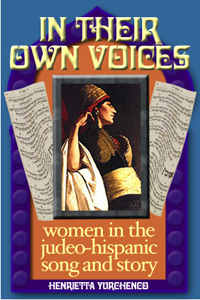

Over time, she branched out into other ethnomusicographical territory. One of the most significant areas of interest for her – and the listening public – was her work in the field of Sephardic Jewish traditional music and folklore. Folkways released her Ballads, Wedding Songs and Piyyutim from the Sephardic Jews of Morocco (1983), a collection of spoken and sung poetry. The piyyutim of the title are Hebrew-language religious poems handed down from the Judaic poet-philosophers of the Middle Ages. (It was a subject to which she returned in her last book In Their Own Voices: Women in the Judeo-Hispanic Song and Story.) Other recordings would appear on, amongst others, Colombia, Decca, Elektra, Mercury, Monitor, Odyssey and Vanguard.

Henrietta ‘Chenk’ Yurchenco’s legacy is scattered over many journals and record labels. She came to be seen as one of the world’s most respected ethnomusicologists, recording social and ritual, traditional and so-called primitive music in many countries. Amongst her collecting forays were trips to Mexico and Guatemala (1942-1946), Mexico (1964-1966, 1971-1972, 1981, 1988 and 1992), Puerto Rico (1967, 1969) and Ecuador, Spain and Morocco (1953-1956), Galicia (1990) and Ireland (1973-1974). She even visited Romania, the German Democratic Republic and Czechoslovakia.

Further reading: Around the World in 80 Years: A Memoir (Music Research Institute, MRI Press, 2003)

14. 3. 2008 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Buddy Miles was best known as a powerhouse drummer, most famously for his work with Jimi Hendrix on Band of Gypsies – the ensemble with bassist Billy Cox – that followed the Jimi Hendrix Experience. It was a short-lived band and the 1970 album, drawing on a New Year’s live set recorded on the cusp of 1969-1970, polarised opinion. The memory most people will have of him was his sound-turned-machine drumming on Machine Gun on Band of Gypsies. Thanks to Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, the sound of helicopter rotor blades…

29. 2. 2008 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Australian folklorist, illustrator, author and one of the pioneers of the Australian Folksong Revival Ron Edwards died on 5 January 2008. He wrote and published extensively over his lifetime on folksong, bushcraft, story telling and linguistics. Simply put, he was a hugely important and influential figure for Australian folk music and anthropology. From 1984 until 2007 he was president of the Australian Folklore Society and edited the Australian Folklore Society Journal. He also wrote widely about Australian folkways, whether Australian folksong, bushcraft or the aboriginal cultures of Australia and the Torres Straits. A skilled painter, he illustrated many of his books himself

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Australian folklorist, illustrator, author and one of the pioneers of the Australian Folksong Revival Ron Edwards died on 5 January 2008. He wrote and published extensively over his lifetime on folksong, bushcraft, story telling and linguistics. Simply put, he was a hugely important and influential figure for Australian folk music and anthropology. From 1984 until 2007 he was president of the Australian Folklore Society and edited the Australian Folklore Society Journal. He also wrote widely about Australian folkways, whether Australian folksong, bushcraft or the aboriginal cultures of Australia and the Torres Straits. A skilled painter, he illustrated many of his books himself

Edwards was born in Geelong, Victoria on 10 October 1930. He was raised in an almost pre-industrial, pre-mechanised agricultural and fishing community. People made their own amusement, singing songs, doing recitations, visiting neighbours.

Amongst his books about the folklore and customs of the Torres Straits – situated between Australia and New Guinea – are Songs from Coconut Island, Songs from Darnley Island, Songs from Dauan Island, Songs from Murray Island, Songs from Saibai Island, Songs from Stephen Island, Songs from Wararber Island and Songs from Yorke Island. You get the picture.

Others included jointly credited works, with Anne Edwards, like An Explorers Guide to Kubin, An Explorers Guide to St Pauls, Moa Island and Children of the Torres Strait. The Torres Straits hold a particular vibrancy in British ethnomusicology. The earliest wax cylinder recordings were recorded there, ushering in a new generation of field recording, one no longer reliant on pen and paper. They are now amongst the 3000 or so surviving wax cylinders held in the British Library Sound Archive. The earliest in the collection are those made by Alfred Court Haddon on his anthropological expedition in 1898-9 to the Torres Straits.

Probably his most important work will prove to be The Big Book of Australian Folk Song (1976). It contained 308 songs and was about seven centimetres thick. But he exceeded even that with the 12-volume Australian Folk Songs. Thankfully this limited edition also went into a read-only CD-ROM edition.

For more about his contemporary Edgar Waters (1925-2008) on this site, visit http://kenhunt.doruzka.com/index.php/edgar-waters-1925-2008/

21. 2. 2008 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] A native Californian, the singer and songwriter and one-time member of the Kingston Trio folk group, John Stewart was born in San Diego on 5 September 1939. Stewart’s album California Bloodlines (1969) and Cannons in the Rain (1973) were major additions to a literature of America in song. Major milestones too. His Mother Country typifies the reflective nature of his finest songs. Like the work of the Canadian songwriter Ian Tyson, Mother Country…

27. 1. 2008 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Telugu singer, dancer-choreographer and actress Tangutoori Surya Kumari – also rendered Suryakumari – was born in Rajamundry in November 1925. She became part of the Raj-era independence movement against the British that eventually triumphed with the end of colonial rule in 1947. She was a child-actress in Telugu films as early as 1937 when a part was written for her in Vipranarayana. Thereafter she juggled cinematic acting and playback singing roles…

8. 1. 2008 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Back in the 1960s, our understanding of the world’s varied musical traditions was woefully ignorant by today’s standards. If buying American blues or bluegrass albums was an expensive undertaking involving the adventure of a day’s expedition to nearest big city or crossing fingers or sending money to a mail order specialist, maybe in another country, then tracking down what was then called “International folk” – like Japonese court music – was similar to shopping on the moon. It could take decades to track down some choice morsel.

8. 1. 2008 |

read more...

« Later articles

Older articles »

[by Ken Hunt, London] The folklorist, folk and ethnic music collector, author, radio broadcaster and producer Henrietta Yurchenco died in Manhattan on 10 December 2007 at the age of 91. She was one of the great links between the racially integrated and progressive-minded US folk scene of the 1930s and 1940s and the folk boom of the 1950s and 1960s, Over the course of her long life in music – the title of her autobiography Around the World in 80 Years (2003) was apt – she was a shaping influence in what people understood by folk music and a kingpin of ethnomusicology and world music.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The folklorist, folk and ethnic music collector, author, radio broadcaster and producer Henrietta Yurchenco died in Manhattan on 10 December 2007 at the age of 91. She was one of the great links between the racially integrated and progressive-minded US folk scene of the 1930s and 1940s and the folk boom of the 1950s and 1960s, Over the course of her long life in music – the title of her autobiography Around the World in 80 Years (2003) was apt – she was a shaping influence in what people understood by folk music and a kingpin of ethnomusicology and world music. In New York City the Yurchencos hooked up and mingled with people in the arts and of similar political persuasions. One thing that happened soon after arriving in NYC was her decision to opt for a post with station WNYC rather than follow a classical piano future (though she continued to play piano for the rest of her life). At WNYC rather than become one of the ‘backroom boys’ or an anonymous continuity voice, she became a name broadcaster. She presented Adventures in Music, a show dedicated to broadcasting the likes of the Almanac Singers, Woody Guthrie, Aunt Mollie Jackson, Huddie ‘Leadbelly’ Ledbetter, Pete Seeger and Josh White. “All of them,” she recalled, “with the exception of Leadbelly, were politically conscious.” Leadbelly was no doubt shrewd enough to keep what politics he had to himself. He certainly had cause enough in a, politically speaking, carcinogenetic era.

In New York City the Yurchencos hooked up and mingled with people in the arts and of similar political persuasions. One thing that happened soon after arriving in NYC was her decision to opt for a post with station WNYC rather than follow a classical piano future (though she continued to play piano for the rest of her life). At WNYC rather than become one of the ‘backroom boys’ or an anonymous continuity voice, she became a name broadcaster. She presented Adventures in Music, a show dedicated to broadcasting the likes of the Almanac Singers, Woody Guthrie, Aunt Mollie Jackson, Huddie ‘Leadbelly’ Ledbetter, Pete Seeger and Josh White. “All of them,” she recalled, “with the exception of Leadbelly, were politically conscious.” Leadbelly was no doubt shrewd enough to keep what politics he had to himself. He certainly had cause enough in a, politically speaking, carcinogenetic era. Her 1970 book A Mighty Hard Road, an important addition to the folk music literature, would be Guthrie’s first major biography. (“When I was writing my biography of Woody Guthrie [.] I asked permission to use [Dylan’s] Song To Woody featured on his first album,” she wrote. “It took six months before I received an answer. He granted permission, but only after reading my manuscript.”) Her perspective and experience meant she became an important participant in the historical discourse. She and Pete Seeger are to be seen on film, for example, reminiscing about the folksinger and folk music collector Alan Lomax in Rogier Kappers’s superb documentary Lomax: The Songhunter (2005).

Her 1970 book A Mighty Hard Road, an important addition to the folk music literature, would be Guthrie’s first major biography. (“When I was writing my biography of Woody Guthrie [.] I asked permission to use [Dylan’s] Song To Woody featured on his first album,” she wrote. “It took six months before I received an answer. He granted permission, but only after reading my manuscript.”) Her perspective and experience meant she became an important participant in the historical discourse. She and Pete Seeger are to be seen on film, for example, reminiscing about the folksinger and folk music collector Alan Lomax in Rogier Kappers’s superb documentary Lomax: The Songhunter (2005). [by Ken Hunt, London] The Australian folklorist, illustrator, author and one of the pioneers of the Australian Folksong Revival Ron Edwards died on 5 January 2008. He wrote and published extensively over his lifetime on folksong, bushcraft, story telling and linguistics. Simply put, he was a hugely important and influential figure for Australian folk music and anthropology. From 1984 until 2007 he was president of the Australian Folklore Society and edited the Australian Folklore Society Journal. He also wrote widely about Australian folkways, whether Australian folksong, bushcraft or the aboriginal cultures of Australia and the Torres Straits. A skilled painter, he illustrated many of his books himself

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Australian folklorist, illustrator, author and one of the pioneers of the Australian Folksong Revival Ron Edwards died on 5 January 2008. He wrote and published extensively over his lifetime on folksong, bushcraft, story telling and linguistics. Simply put, he was a hugely important and influential figure for Australian folk music and anthropology. From 1984 until 2007 he was president of the Australian Folklore Society and edited the Australian Folklore Society Journal. He also wrote widely about Australian folkways, whether Australian folksong, bushcraft or the aboriginal cultures of Australia and the Torres Straits. A skilled painter, he illustrated many of his books himself