Articles

[by Ken Hunt, London] What a year for music! The number of events of 2011 on this list is greedy by most annual polls’ standards. One of the continual difficulties for me is that, because I am writing in a variety of periodicals and newspapers across a variety of musical genres for a number of territories, wonderful stuff just gets continually squeezed out. I mean, in this brave new world of world music, nobody wants ten roots-based Czech or Hungarian albums or Indian classical or English or even European folk albums…

[by Ken Hunt, London] What a year for music! The number of events of 2011 on this list is greedy by most annual polls’ standards. One of the continual difficulties for me is that, because I am writing in a variety of periodicals and newspapers across a variety of musical genres for a number of territories, wonderful stuff just gets continually squeezed out. I mean, in this brave new world of world music, nobody wants ten roots-based Czech or Hungarian albums or Indian classical or English or even European folk albums…

2011 was marked by losses in the world of music. It started off with the deaths of the singers Bhimsen Joshi and Suchitra Mitra. Keeping to that subcontinental frame of mind, as the year crunched on, the rudra vina virtuoso Asad Ali Khan, the film-maker Mani Kaul, the ghazal and more maestro Jagjit Singh, Assam’s treasure Bhupen Hazarika and the sarangi player Sultan Khan died. Mauritania’s songstress supreme, Dimi Mint Abba and the Cape Verdean singer Cesária Évora, and the song creators Franz Josef Degenhardt and Ivan ‘Magor’ (Madman) Jirous died. And particularly heartfelt for me, there were the deaths of three mainstays of the British folk revival and scene – Mike Waterson, Ray Fisher and Bert Jansch (and then Loren Jansch). And last, there was Václav Havel’s death, not long after Ivan Jirous’s death.

New releases

New releases

Amira / Amulette / World Village

Asha Bhosle & Shujaat Khan / Naina Lagaike / Saregama

Kristian Blak & Yggdrasil / Travelling / Tutl

Eliza Carthy / Neptune / Hem Hem

Andrew Cronshaw / The Unbroken Surface of Snow / Cloud Valley Music

Steve Earle / I’ll Never Get Out Of This World Alive / New West Records

Arun Ghosh / Primal Odyssey / Camoci

Jayanthi Kumaresh / Mysterious Duality / EarthSync

Laura Marling / A Creature I Don’t Know / Virgin

Tommy McCarthy / Round Top Wagon / ITCD http://www.tinfolkmusic.com/www.tinfolkmusic.com/Thomas_McCarthy.html

Christy Moore / Folk Tale / Sony Music (Ireland)

Nørn / Urhu / own label / www.norn.ch

Llio Rhydderch and Tomos Williams / Carn Ingli / Flach

Mike Seeger and Peggy Seeger / Fly Down Little Bird / Appleseed

Jyotsna Srikanth / Carnatic Jazz / Swathi Soft Solutions

Ági Szalóki and Gergő Borlai / Kishúg / Folk Európa Kiadó

June Tabor / Ashore / Topic

June Tabor & Oysterband / Ragged Kingdom / Topic

Trembling Bells / The Constant Pageant / Honest Jon’s

Historic releases, reissues and anthologies

Historic releases, reissues and anthologies

Peter Bellamy / Merlin’s Isle of Gramarye / Talking Elephant

Z.M. & Z.F. Dagar / Ragini Miyan ki Todi / Country & Eastern

Grateful Dead / Europe ’72 Vol. 2 / Grateful Dead Productions

Grateful Dead / Europe ’72: The Complete Records – Wembley Empire Pool, London, England 4/8/72 / Grateful Dead Productions

Home Service / Live 1986 / Fledg’ling

The Kinks / Something Else By The Kinks / Sanctuary

Muzsikás / Fly Bird Fly / Nascenti

Ravi Shankar / Reminiscence of North Vista / East Meets West Music

Ravi Shankar / Orchestral Experimentations / East Meets West Music

Leon Rosselson / The World Turned Upside Down / PM Press/Fuse Records

M.S. Subbulakshmi / Surdas Bhajans / Charsur Digital Workstation

Traffic / John Barleycorn Must Die (Deluxe) / Universal

Various Artists / The Complete Pakeezah / Saregama

Various Artists / The Rough Guide to English Folk / World Music Network

Various Artists / Antologie moravské lidové hudby/Traditional Folk Music in Moravia – Horňácko / Indies

Various Artists / Antologie moravské lidové hudby/Traditional Folk Music in Moravia – Dolňácko I / Indies

Various Artists / A Népzenét‹l a Világzenéig 1 From Traditional to World Music / Folk Európa Kiadó / Folk Európa Kiadó

Various Artists / A Népzenét‹l a Világzenéig 2 From Traditional to World Music / Folk Európa Kiadó

Various Artists / A Népzenét‹l a Világzenéig 3 From Traditional to World Music / Folk Európa Kiadó

Hedy West / Ballads and Songs from the Appalachians / Fellside

Events of 2011

Events of 2011

‘The Contenders’ – Sam Lee, Emily Portman, Massie and Alex Nielson / Queen Elizabeth Hall, London / 14 January 2011

Archie Fisher / Twickfolk, The Cabbage Patch, Twickenham, Middlesex / 15 January 2011

‘A Tribute to Ustad Ali Akbar Khan’ – Alam Khan / Darbar Festival, Hall One, Kings Place, London / 23 April 2011

Marry Waterson & Oliver Knight / Royal Oak, Lewes, Sussex / 5 May 2011

The Folk Jukebox / Royal Festival Hall, London / 7 May 2011

‘Flying Man (Pakshi-Manab): Poems for the 21st Century’ – Mukal Ahmed, Munira Parvin, William Radice, Idris Rahman and Zoe Rahman / Conference Centre, British Library, London / 17 May 2011

Ravi Shankar / 21 June 2011 / Barbican Hall, London

Nørn / Tanz&FolkFest Rudolstadt, Stadtkirche, Rudolstadt / 3 July 2011

Aruna Sairam / BBC Proms Prom 17: World Routes Academy, Royal Albert Hall, London / 27 July 2011

‘Masters of Percussion’ – Zakir Hussain (tabla) with Rakesh Chaurasia (bansuri), Ganesh Rajagopalan (violin), Sridar Parthasarathy (mridangam and kanjira), Navin Sharma (dholak) and T.H.V. Umashankar (ghatam) / London Jazz Festival, Royal Festival Hall, London / 11 November 2011

Peggy Seeger / Folk Union, Hall Two, Kings Place, London / 18 November 2011

Images: Aruna Sairam and Hari Sivanesan on vina © Santosh Sidhu/Swing 51 Archives. Otherwise the images are © their image-makers, photographers and designers.

31. 12. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Back in New York, Seeger enthused about what he had seen and heard. Broadside, a publication with a tiny circulation – using, as Sis Cunningham recalled, a hand-cranked mimeo machine “we had inherited when the American Labor Party branch closed in our neighbourhood” – became a vital conduit for song. Originally published fortnightly, very soon monthly, topicality was a major goal. It published its first issue in February 1962 and folded in 1988. By comparison Sing was launched on May Day 1954 and Sing Out! had first appeared in 1950. Unlike Sing Out! or Sing, Broadside did not interleaf traditional songs with its songs of struggle, diatribes on themes of social justice or political squibs. However imprecisely or colloquially some dubbed this latter category ‘folksongs’ – much to the exasperation of the folklorists and the outrage of armchair scholars who took the fight to numerous letters columns – Broadside‘s first issue carried the slogan “A handful of songs about our times” beneath its name.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Back in New York, Seeger enthused about what he had seen and heard. Broadside, a publication with a tiny circulation – using, as Sis Cunningham recalled, a hand-cranked mimeo machine “we had inherited when the American Labor Party branch closed in our neighbourhood” – became a vital conduit for song. Originally published fortnightly, very soon monthly, topicality was a major goal. It published its first issue in February 1962 and folded in 1988. By comparison Sing was launched on May Day 1954 and Sing Out! had first appeared in 1950. Unlike Sing Out! or Sing, Broadside did not interleaf traditional songs with its songs of struggle, diatribes on themes of social justice or political squibs. However imprecisely or colloquially some dubbed this latter category ‘folksongs’ – much to the exasperation of the folklorists and the outrage of armchair scholars who took the fight to numerous letters columns – Broadside‘s first issue carried the slogan “A handful of songs about our times” beneath its name.

Many froze not only the fleeting moment but the urgency of the search for the three-chord trick or, in some cases, that elusive third chord. Many strove to out-Dylan Dylan too. Union solidarity songs figured prominently, such as Hazard, Kentucky which appears on Phil Ochs’ The Broadside Tapes 1 and El Teatro Campesino’s El Picket Sign on The Best of Broadside. There again Ochs also sang the gloriously throwaway and irreverent Christine Keeler based on the Profumo episode – as was Matt McGinn’s Christine delivered by the Broadside Singers with Tom Paxton and Pete Seeger. Yet sprinkled through the pages of those early issues were songs that got a life, so to speak, and took on lives of their own. Songs like Janis Ian’s Society’s Child, Seeger’s Waist Deep In The Big Muddy, Bonnie Dobson’s Morning Dew and Nina Simone’s Mississippi Goddam spread like wildfire. “These songs were springing from the Civil Rights movement and from the burgeoning opposition to the Vietnam War,” Cunningham wrote.

Broadside was known in Britain by repute at least even if few ever saw a copy over its entire lifespan. Like Sing Out! and Little Sandy Review, it had a reputation way beyond the meagre quantities that got into Collet’s or elsewhere. Pete Frame, later the co-founder of Zigzag, picked up Broadside “as assiduously as [he] could” but Martin Carthy, for example, has no memory of ever seeing a copy. “What happened,” remembers Frame, “was that the record shop – Collet’s – at 70 New Oxford Street used to get them in sporadically but not on a regular basis. They used to get all these various folk music magazines from various places. Such as Sing Out!, Broadside and a different Broadside that was published from Boston. I used to buy them when and as I could find them. Broadside never got there that regularly. I also had those Broadside records. I certainly got the original of the one with Blind Boy Grunt.”

Frame hits it on the head. The main reason why people remember Broadside was that farcical alias. Blind Boy Grunt was Bob Dylan. Bell-wether or scapegoat by turn, completists collected Dylan’s every fart, belch and stomach grumble, as perhaps only jazz zealots had ever pursued their quarry before him. Blind Boy Grunt had three tracks on the Broadside Ballads, Vol. 1, released in 1963. The Broadside link would soon stretch to Dylan’s singing on Vanguard’s Newport Broadside (Topical Songs) – a wily remora of a title – and Broadside’s We Shall Overcome and the much later Broadside Reunion.

Less difficult to get hold of than the magazine itself was Oak Publications’ “songs of our time from the pages of Broadside magazine” anthology. “I also got an omnibus edition of Broadside,” Frame recollects. “It was pages from the magazine with something like 88 different songs. That came out in 1964, with illustrations by Suze Rotolo – Dylan’s girlfriend – and people like that. You would have a song per page. Or a song every two pages, like Train A-Travelin’ by Bob Dylan that came out of Broadside #23 – that had an illustration by Suze Rotolo. It was a typical early song by Dylan. It’s got Paths of Victory by Dylan, Mississippi Goddam by Nina Simone, With God On Our Side, and stuff by Phil Ochs, Tom Paxton and so on. It also had a long introduction with pictures of these guys and little notes about them.” Unbelievably by today’s information overload standards, back then the sum of the knowledge about many American performers was little more than the potted biog or puff on the back of an EP or LP.

Broadside was primarily a domestic phenomenon. Songs such as Thom Parrott’s Pinkville Helicopter, Matt Jones and Elaine Laron’s Hell, No, I Ain’t Gonna Go and Seeger’s Ballad of the Fort Hood Three remind how Vietnam overshadowed American society. Seeger’s Waist Deep In The Big Muddy on the other hand transcends the period and the particular to become a timeless anti-militarist song, up there with John B. Spencer’s Acceptable Losses and Robert Wyatt’s Shipbuilding. Quite reasonably, Broadside mostly saw life through an American prism. Yet commonalities abounded. The characters on the identity parade looked similar when Malvina Reynolds sang The Faucets Are Dripping about decaying properties and exploitative landlords in New York and Stan Kelly sang Fred Dallas’ Greedy Landlord about slum landlords in Rachman’s London or Paddy Ryan’s The Man That Waters The Workers’ Beer about short-measuring and exploitation. Exchanges occurred freely. The Glasgow Song Guild’s Ding Dong Dollar on the Broadside set was also printed in a C.N.D. songbook. Songs by Woody Guthrie, Lee Hays and Pete Seeger, Irwin Silber and Jim Garland appeared in the Y.C.N.D.’s Songs of Hope and Survival songbook.

Even though Broadside published a smattering of topical songs from European and Canadian songwriters, songs such as Wolf Biermann’s Soldat and Das Familienbad, Buffy Sainte-Marie’s Welcome, Welcome Emigrante and Matt McGinn’s Go Limp, it never meant as much in Britain, Europe or, a hunch, Canada as it did at home. “I don’t think Broadside had the same sort of meaning over here,” Rosselson concedes. “There was a very strong British equivalent over here, which was clearly much more interesting to British songwriters than the American version. My memory is that it didn’t have that big an impact here but over there Broadside was, in a way, the beginning of the protest movement over there.”

Seeger with trademark perspicacity, though he would probably pooh-pooh such a ‘compliment’, saw something important in 1961. It was the power of song, a vision at variance with what became the cult of the songwriter. He wanted songs put into circulation, maybe that one good that is in everybody, maybe more, and he wanted songs sung and shared. In the liner notes to his 1964 album I Can See A New Day Henrietta Yurchenco wrote, “About fifteen years ago, Les Rice, a shy farmer and ironwork craftsman from Newburgh, New York, wrote the Banks of Marble, a song which was taken up quickly throughout the English-speaking world. For many years he was silent. When Broadside began publication in 1962, Pete Seeger urged his friend and neighbour to start composing again. I Can See A New Day was Rice’s contribution to the new topical folk-song periodical.” Typical Seeger. “I really urge singers,” he told me in 1993, “to think of themselves not as a singer whose business it is to make people listen and applaud. Think of yourself as a singer who will show people what a great song you have and encourage them that they can sing it too – long after you’re gone. Not to say, ‘Oh, I must get them to buy my record.’ Or get them to buy this or that.”

They say in their lifetime the average citizen gets to make fifteen or so crosses on the ballot paper. The Best of Broadside contains scores of blueprints about how to register other sorts of vote. There are still countless themes of social justice waiting to be turned into song. How could the Labour Party’s ho-ho-ho ‘freedom of information’ proposals not incite a new batch of sceptics and their songs so long as fears about the absolute basics – food, water, air and health – are secondary to profit. As long as the boa constrictor of multinational business can pleasantly massage and lull so many people into a false feeling of security about genetically modified food and other environmental issues, warning bells must ring.

Once upon a time, small, cheaply produced folk rags like Broadside and Sing informed through song, reminded people about the benefits of solidarity. Nowadays when so much that is politically radical or looking to alternatives, whether in China, Britain or wherever, has switched to the Internet, there might be the suspicion that topical song’s time is past. During February and March 2001 under the collective title of The Magnificent 7, Robb Johnson, Attila the Stockbroker, Barb Jungr, Des De Moor, Tom Robinson, Phillip Jeays and Leon Rosselson did a seven-week season of “contemporary English chanson”. So called because, as Leon Rosselson explains, “it’s a broader category and these songs are definitely not American and may have a European influence, particularly French, and like the French chanson they are word-based, literate, intelligent and that sort of thing.” It would have thrilled Pete Seeger. Chronicling the march of political and topical song, the centre for political song at the Glasgow Caledonian University is archiving the past. The need still remains for new topical songs. The need remains to chronicle the past. Song remains one of the most effective ways yet devised by the human mind to express opinions. The Best of Broadside is more than American history. In 1963 when Phil Ochs wrote the Ballad of William Worthy about a reporter whose U.S. passport was revoked after going to Cuba, would be have imagined the Cuban embargo still going on in 2001 and what should have been history still retaining its point and pertinence?

More information at http://www.folkways.si.edu/explore_folkways/BestBroadside.aspx

19. 12. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The one has a lot to do with thinking about loss and renewal, life and the end of life. The music is provided by Anoushka Shankar, David Crosby, Jayanti Kumaresh, Judy Collins, Chumbawamba, Franz Josef Degenhardt, Sultan Khan and Manju Mehta, Ági Szalóki and Gergő Borlai, Davy Graham and Federico García Lorca.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The one has a lot to do with thinking about loss and renewal, life and the end of life. The music is provided by Anoushka Shankar, David Crosby, Jayanti Kumaresh, Judy Collins, Chumbawamba, Franz Josef Degenhardt, Sultan Khan and Manju Mehta, Ági Szalóki and Gergő Borlai, Davy Graham and Federico García Lorca.

Bulería con Ricardo – Anoushka Shankar

This comes from Anoushka Shankar’s debut for Deutsche Grammophon, a fusion affair that travels the continents from modern-day north-west of the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent to the Iberian peninsula. Anoushka Shankar plays sitar, Pedro Ricardo Mieo piano, Juan Ruiz adds unspecified “Spanish percussion” and Bobote and El Eléctrico palmas (hand claps). It’s a feast of fun and should Anoushka Shanka, also a trained pianist, gets to collaborate with the flamenco pianist David Peña Dorantes there is no knowing where things might go. From Traveller (Deutsche Grammophon 477 9363, 2011)

Tamalpais High (At About 3) – David Crosby

I slid my nail through the shrink-wrapped LP in 1971 in Itzehoe. I had splurged good West German marks on an import copy from a record shop in Hamburg. It was one of the best purchases of my life. Crosby’s first solo album was and remains a gem.

I had no idea what had inspired his Tamalpais High (At About 3) musical adventure. I know now, but that is irrelevant. That is not the point of music. The point of music is the seeds it sows. We can review and change our thoughts about a piece of music as we age. We can also hold more than one interpretation. Many years later, I was sitting with a friend of my son’s age in San Rafael looking up to Mount Tamalpais. I told him a story about a friend’s son having died at the top of Tamalpais. I wept and let years of bottled up emotion pour out, as we talked about David Crosby, Los Lobos and the Pogues. One of the most cathartic experiences of my life. From If I Could Only Remember My Name (Atlantic/Rhino R2 73204, 2006)

Mysterious Duality – Jayanti Kumaresh

This is the title track from one of my albums of the year. The vainika (vina or veena player) Jayanti Kumaresh has the senior Karnatic violinist Lalgudi Jayaraman as a maternal uncle while her aunt is Padmavathy Ananthagopalan, with whom she studied vina. She also studied with S. Balachander (1927-1990), contender for firebrand vainika of recent times. This project is where so much comes together and where she reveals herself as one of the most promising vainikas of our day. Very Twentieth-first century with a few generations of musical glory as back-up. From Mysterious Duality (EarthSync ES0038, 2010)

My Father – Judy Collins

My Father – Judy Collins

My Father originally appeared on Judy Collins’ Who Knows Where The Time Goes (1968). The arrangements and overall feel were a departure, for gathered around her were musicians capable of delivering folk-rock arrangements. There was something special about the sound of David Anderle’s production, just as there had been with Mark Abramson’s Wildflowers. On this track she was joined by Michael Melvoin on piano, Stephen Stills on electric guitar, Chris Etheridge on electric bass and James Gordon on percussion. She plays electric piano.

Reading her autobiography, Trust Your Heart (Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1987) recently, I came to an appreciation of this song that I had never had hitherto. I love the way she conflates her family’s history (she is the eldest of four siblings, not the youngest) in this Parisian fantasy. A key discovery, however, was reading that her dad had been blind. My Father’s poignant lines “And watch the Paris sun/Set in my father’s eyes again” took on new meaning. From Wildflowers & Who Knows Where The Time Goes (Rhino 8122 73393-2, 2006)

Salt Fare, North Sea – Chumbawamba

This song of Chumbawamba’s that uses a vocal sample from Lal Waterson’s Some Old Salty re-entered my imagination because it opens their Readymades – a project that I view as, crudely put, Britain’s answer to Beck’s visiting of the Alan Lomax Archives, but with the good manners to ask first. I was listening to it for as background research for an article about Davey Graham – whose Anji is prominent in the next track Jacob’s Ladder and somehow I wound up playing Salt Fare, North Sea and Jacob’s Ladder over and over. Chumbawamba continually tickle my fancy. One day I shall write about them properly. From Readymades (Mutt Records LC-12157, 2002) http://www.chumba.com/

Café nach dem Fall – Franz Josef Degenhardt

Café nach dem Fall – Franz Josef Degenhardt

Flying back from Prague via Frankfurt am Main to London had been hellacious. Fog blanketed Ruzyně airport (PRG) and the Lufthansa plane permitted to fly out of the fog banks took on a bunch of people from a cancelled flight to Munich. At some point I unfolded the Frankfurter Allgemeine and let out a cry on discovering that Franz Josef Degenhardt had died. His death was on the front page of the newspaper.

Franz Josef Degenhardt shaped my expanding worldview and consciousness about politically engaged song when I first discovered him in my bosom buddy, Michael Moser’s record collection in Itzehoe in 1971. Later Franz Josef and I corresponded, put in touch with each other by his sister-in-law, the illustrator Gertrude Degenhardt. Many songs could have hit me in the aftershock of learning that he had died. This was the one. I love the sweep of his vision. It’s a list song multiplied many times. He’s a shameless old name-dropper and I love this suite all the more for it. He ranges from “Karl & Groucho Marx, Che Guevara & Bill Gates” (straightaway introducing the café’s nay-sayer, the garlic-eater (Knoblauchfresser) to the Rolling Stones and the Beatles. And it just goes on and on. (Many thanks to the Lufthansa crew on that fraught flight, too.) From Café nach dem Fall (Polydor 543 615-2, 2000)

Ken Hunt’s FJD obituary in The Independent of 23 November 2011 is at http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/franz-josefdegenhardt-musician-and-hero-of-the-counterculture-6266187.html

Rāg Kaunsi Kanada – Sultan Khan and Manju Mehta

I first met the sarangi maestro Sultan Khan when he did an all-nighter cushion concert with the father and son tabla maestros, Alla Rakha and Zakir Hussain in London in 1981. I first met the sitar virtuoso Manju Mehta, the sister of Vishwa Mohan Bhatt, at the Harballabh in Jalandhar in 2008. This is a duet recording from the 2004 Saptak Festival in Ahmedabad in Gujarat. After Sultan Khan’s death on 27 November 2011 I listened again and again to Soja Re (Go To Sleep) from the now out-of-print compilation Rough Guide To India as I started writing his obituary. Then I looked at the pile of Sultan Khan CDs beside me. I decided that this remarkable interpretation of Kaunsi Kanada was what I needed to listen to… From Umeed (Sense World Music 104, 2008)

Vörösbor – Ági Szalóki and Gergő Borlai

Vörösbor – Ági Szalóki and Gergő Borlai

Kishúg is a marked departure for Ági Szalóki. On this album she lights out for, for her, new rock and world music territory. Much of the keyboard- and drum-saturated sound of Kishúg, in what seems to me, as the former London correspondent for El Cerrito, CA’s Keyboard magazine, to champion a retro vibe in an unapologetic way that you don’t hear much nowadays.

Listening through to this album I would suspend judgement and put this track on repeat (the way reviewers do) in order to mull over what was in the mix. I took me weeks for me to puzzle why this track did it for me. It was the Latin style percussion reminding me of the tasteful frenzy of Gene Clark’s masterpiece No Other and Ági Szalóki’s vocal. Maybe the track is more of a vibe than a song. Doesn’t matter.

Vörösbor (Red wine) shows off her vocal talent splendidly, a talent that is not reliant on understanding a word of Hungarian. (There are no translations of the lyric.) Powerful voice. Effervescent stuff. From Kishúg (Folk Európa Kiadó FECD 053, 2011)

More information at http://szalokiagi.hu/index-main.html

Photo © 2011 András Hajdu, courtesy of Ági Szalóki

She Moved Through The Fair – Davy Graham

This is one of those before-and-after performances. What was before? What flowed afterwards? It appears as the fourth track on this Dave Suff-compiled double-CD anthology – essential if you have never heard the wonders that were Davy (later, Davey) Graham. I cannot say that I knew him well but I did know him for a fair few years, interviewed him and corresponded with him over many years. This is one of his performances that remains for me a demonstration of his uniqueness.

My Davey Graham entry is in the January 2012 edition of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. This is the sort of music that guaranteed him a place in that history of British culture told through biography. From A Scholar and a Gentleman (Decca 532 263-1, 2009)

Zorongo gitana – Federico García Lorca and La Argentinita

Zorongo gitana – Federico García Lorca and La Argentinita

I had forgotten that Lorca (1898-1936) had recorded music, let alone flamenco, although I knew of his flamenco connections and advocacy. I found this CD in a second-hand record shop. The last four tracks of this album have him accompanying the Buenos Aires-born Encarnacín López ‘La Argentinita’ (1895-1945) on piano in 1931. La Argentinita sings and adds hand and foot percussion, but her flamenco is diaspora flamenco and a signpost to later diaspora musical movements.

I have no idea about the availability of this recording, but for me, Lorca is one of my borrowed ancestors.

This is one of those tiny treasures. From In Memoriam (EMI (Spain) CDM 5 66783 2, 1998)

Ági Szalóki’s portrait is by András Hajdu and appears courtesy of Ági Szalóki. The copyright of the other images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers.

5. 12. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] It’s 2001. You open the paper at an article about the underground strike. Par for the course, the same old politicians are lip-synching the party line. Substitute the specific till the capitalist or metropolitanist becomes local to you. The London Underground is being turned into another public-private partnership. The workers are striking about compulsory redundancies, fears over safety, etc. You get incensed. Another sodding disruption. Another sodding protest. Another sodding privatisation gussied up, as London’s transport commissioner Bob Kiley – remember him, New Yorkers? – decries, to generate “the least expensive product or service at the highest price.” Wasn’t that a time when songs would have flowed about the Tory Party ripping apart the national rail system and Labour chuffing along complacently behind them toking on their exhaust fumes?

[by Ken Hunt, London] It’s 2001. You open the paper at an article about the underground strike. Par for the course, the same old politicians are lip-synching the party line. Substitute the specific till the capitalist or metropolitanist becomes local to you. The London Underground is being turned into another public-private partnership. The workers are striking about compulsory redundancies, fears over safety, etc. You get incensed. Another sodding disruption. Another sodding protest. Another sodding privatisation gussied up, as London’s transport commissioner Bob Kiley – remember him, New Yorkers? – decries, to generate “the least expensive product or service at the highest price.” Wasn’t that a time when songs would have flowed about the Tory Party ripping apart the national rail system and Labour chuffing along complacently behind them toking on their exhaust fumes?

Rewind to the early 1960s. Phil Ochs, the Greenwich Village voice, is riding the New York subway heading to the office of Broadside magazine to deliver some hot new tidbit. He and Malvina Reynolds are the most prolific of the so-called Broadsiders. Both are forever rattling off songs to meet the needs of the hour. Having studied journalism at Ohio State, Ochs is avidly reading the New York Times on his way to the Upper West Side. A couple of news items have hotwired his creative juices.

Sis Cunningham, who co-edited Broadside with her husband George Friesen, recalled Ochs in their autobiography Red Dust and Broadsides: “Phil would come around and say, ‘I’ve got seven new songs.’ We’d say, ‘What! Seven new songs?’ So he said, ‘Yeah.’ And Gordon would ask him, ‘Well, where do you get all your material?’ He’d say, ‘Well, I get it out of the newspapers and out of Newsweek. I wrote two of them on my way up here on the subway from the Village.'” Broadside took topicality hot-off-the-subway but, broadmindedly, even took songs on which the ink was already dry. Confusingly, in a frenzy of parallel evolution, three Broadsides emerged around the same period in New York, Boston and Los Angeles. New York’s is the one to which Smithsonian Folkways has dedicated a five-CD, spiral-bound, slip-cased set called Best of Broadside 1962-1988: Anthems of the American Underground From the Pages of Broadside Magazine.

When folk music first began brainwashing my generation’s minds during the mid 1960s, for several years it would have been hard to disembarrass lots of us of the notion that there was anyone in the whole wide world of folk who wasn’t at least vaguely lefty. As naive, as patently absurd as that now sounds, droves subscribed to this particular form of less-than-mass delusion. It stood to reason that anyone with a folk bone in his or her body had to hold some sort of suspect leftish or suspiciously bohemian views. Aside from the weekly music rags, Melody Maker and suchlike, the low-circulation folk magazines – many, in the language of The League of Gentlemen, local rags for local people – that were sold in the folk clubs and specialist shops, did little to disabuse about the well-known Communist conspiracy. Sing and its fellow travellers over here, the market leader Sing Out! and the more recherché Broadside over there reinforced such views. Here later folk pulpit pamphleteers – Karl Dallas’ name looms especially large – kept the red flag flying. That said, the first half of the 1960s saw a variety of magazines operating in the general folk field in Britain including Ballads & Songs, Folk Music, Folk Scene and Spin and not all had political agendas.

Broadside was neither unique nor the first, but its back pages remain a frozen barometer of its times and the folk condition. Even by the homespun standards of the day, Broadside had the feel of the parish pump about it. Clippings from newspapers and magazines provided further insights and raised eyebrows. Electricity had probably never played a major part in the production process and, had a fly formed an attachment to drying cow gum, it would have become immortalized in print for ever more. Broadside had that manual typewriter, pre-photocopier look to it that song folios like Anti-Fascist Songs of the Almanac Singers had had in the 1940s. “I remember the appearance of it,” recalls Gill Cook, who was not a huge fan of the magazine although Collets, the shop she managed, went out of its way to stock as representative a selection of the domestic and international folk magazines as it could. “Broadside was very badly laid out. It was political and I’d really rather gone off that stuff. The best one was Sing Out! There were always one or two political things in Sing Out! but they didn’t thrust it up your nose as much as Broadside. Sing was more local; there would be a few things about ‘foreign music’ but not very often.”

What really counted in Broadside was the songs. The finest were champagne drunk from a chipped enamel mug. Regular contributors included Bob Dylan, Peter La Farge, Tom Paxton and variously combined Broadside Singers. They would come into the office and sing or send tapes and lyrics on spec which would be transcribed and published in the magazine’s pages. Before Fast Folk was a twinkle in its parents’ eyes, Broadside had an archive of performances and some saw releases on the Broadside imprint of Moe Asch’s Folkways label.

In the early 1950s both the British and American folk scenes had formed a commensal relationship. In Britain many American musicians were little more than names with hearsay reputations – who had actually ever heard the Almanac Singers back then? – but others, names like those of Pete Seeger, the Weavers, Josh White, Big Bill Broonzy and Alan Lomax shone like beacons. In an era of L.s.d. currency restrictions and limited opportunities to travel abroad, even Woody Guthrie was best known, and often better appreciated, through Ramblin’ Jack Elliot. It was far from one way traffic though. Ewan MacColl and Bert Lloyd began to seed ideas in the American folkie consciousness from 1956 with The English and Scottish Popular Ballads series released on Riverside. Without getting jingoistic, it is a fact that Britain re-energised America’s songwriting movement that had flagged during the years of McCarthyist and McCarranist oppression.

During the 1950s the US authorities had simultaneously held back the red tide and had fun preventing Pete Seeger from travelling abroad. Argus-eyed red-busters, amateur and professional, had kept watch on Seeger, the other former members of the Weavers and their kind. (In 1968 in a post-McCarthyist lapse of judgement Broadside paraded soi-disant Dylanologist Alan Weberman’s arse-clenchingly sinister “Bob Dylan: What his songs really say” exposés, literally with added trashcan gleanings.) With consummate understatement in her Lonesome Traveler – The Life of Lee Hays Doris Willens remarked, “Controversy stuck to the Weavers like a tar baby”. In 1955 Seeger had been called before the House Un-American Activities Committee and had been sentenced to gaol for contempt of court. The dawning of a new decade brought permission for Seeger to visit Britain. “Khrushchev’s Songbird” had previously toured in 1959 with Jack Elliot but he arrived in the autumn of 1961 with his wife Toshi and daughter Tinya – and promptly discovered something which excited him enormously. He encountered a song movement of unsuspected proportions and vigour. Sometimes under the influence of France’s literary chanson movement, sometimes motivated by dialect or occupation, sometimes channelling political ideas, writers such as Johnny Handle, Stan Kelly and Leon Rosselson were spearheading a new song movement. “These Americans came over,” remembers Rosselson, “and heard me perform, and other people, at some event and I remember how impressed they were by the fact that there were these topical, as they would call them, songs being written over here. There was no equivalent over there. This is way before ‘Protest’ started. The British song of that time that came out of C.N.D., the leftwing political and folk worlds predated the songs in Broadside and the songs they published there. I think it was because they’d heard these songs over here that they decided that they ought to have a magazine that could be a platform for those sort of songs in America.”

To be continued…

More information at http://www.folkways.si.edu/explore_folkways/BestBroadside.aspx

4. 12. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, Prague] Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941, Rabindranath Thákur for my Czech readers) was the all-original singer-songwriter – before the term existed – with the folk poetry touch, a poet-bard who in Scots would be called a makar. He had melody purloining skills to make Woody Guthrie blush. In an era of luxury liners and Pullman trains, he travelled probably about as widely as was possible in that pre-David Attenborough era. He set lyrics to ragas, traditional airs, Baul songs, Ganges boatmen’s work songs and melodies, like Auld Lang Syne (!), heard on his travels. Where he differs from most song-makers is the enduring popularity, relevance and cultural penetration of his work. An unlettered field worker in Bangladesh and a Kolkata university professor are equally likely to have memorised his words.

[by Ken Hunt, Prague] Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941, Rabindranath Thákur for my Czech readers) was the all-original singer-songwriter – before the term existed – with the folk poetry touch, a poet-bard who in Scots would be called a makar. He had melody purloining skills to make Woody Guthrie blush. In an era of luxury liners and Pullman trains, he travelled probably about as widely as was possible in that pre-David Attenborough era. He set lyrics to ragas, traditional airs, Baul songs, Ganges boatmen’s work songs and melodies, like Auld Lang Syne (!), heard on his travels. Where he differs from most song-makers is the enduring popularity, relevance and cultural penetration of his work. An unlettered field worker in Bangladesh and a Kolkata university professor are equally likely to have memorised his words.

Idris Rahman led the participants into the room with a slow processional version of Alo, amar alo, ogo/alo bhuban-bhara (‘Light, light, light, oh light/That fills the world’ in William Radice’s translation) on, to go Indian, clarionet. Radice, a translator-poet who is to Tagore what Coleman Barks is to Rumi, recited from memory or read in English and Bengali while Mukal Ahmed and Munira Parvin concentrated on Tagore’s Bengali originals. Clarinettist Idris and his sister, the pianist Zoe Rahman contributed both sparse accompaniments and extended musical interludes.

When Zoe Rahman took off after Radice and Parvin’s conversational Mayurer Drishti (‘In the Eyes of a Peacock’), it was clear that something other than pianistic improvising was going on. Without fanfare or announcement, they were sneaking in material from her almost completed Kindred Spirits album. It turned out to be the new composition Hridoy Amar Nache Re (‘My heart dances, like a peacock, it dances’). You could read into the music what you liked, maybe coloured by the afterimages of the words you had just heard. The Betjeman-like train rhythms of Ishtesan (‘Railway station’) and technology versus natural world imagery of Pakshi-manab (‘Flying man’) were developed with, respectively, locomotive and station motifs and bird flight and song. Tagore’s response to the Italian invasion of Abyssinia, manacles and slavers and the horrors of colonialism were sharp-focussed in Tagore’s Africa piece. For it, the Rahmans chose Abdullah Ibrahim’s Ishmael as their opening text before going into Tagore’s Hridoy Amar Prokash Molo (‘My heart…’) with glancing allusions to one of his greatest hits, Akash Bhora Surjo Tara (‘The sky is full of the sun and stars’). 150 years on from his birth, this evening magically confirmed and celebrated Tagore’s continued relevance.

William Radice’s and Ken Hunt’s articles about Tagore appear in Pulse‘s Spring 2011 issue celebrating Tagore. More information at http://www.pulseconnects.com/

For more information about Zoe Rahman go to http://www.zoerahman.com/

For more about Tagore’s Czech connections, I recommend time spent reading David Vaughan’s piece here in print and/or listening to its audio file: http://www.radio.cz/en/section/books/rabindranath-tagore-an-indian-poet-who-inspired-a-czech-generation

14. 11. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] This month’s batch has a lot to do with thinking about rhymes, rhythms, mythologies and conversations. Bert Jansch, Hedy West, La Piva Dal Carner, Grateful Dead, Jagjit Singh & Chitra Singh, Laura Marling, Marvin Gaye, Rapunzel & Sedayne, David Lindley y Wally Ingram, and Ali Akbar Khan supply this month’s inspirations.

[by Ken Hunt, London] This month’s batch has a lot to do with thinking about rhymes, rhythms, mythologies and conversations. Bert Jansch, Hedy West, La Piva Dal Carner, Grateful Dead, Jagjit Singh & Chitra Singh, Laura Marling, Marvin Gaye, Rapunzel & Sedayne, David Lindley y Wally Ingram, and Ali Akbar Khan supply this month’s inspirations.

Nottamun Town – Bert Jansch

Nottamun Town – Bert Jansch

No apologies for returning to Bert Jansch’s 1966 album once again. It was playing as the news broke on the morning of 5 October 2011 that he had died in the wee small hours. I have known and extolled Jack Orion since the year of its release. It had depths and darknesses unlike any of his two previous solo releases, in part because of his embracing of traditional material. Even the LP’s design signalled a bleakness or austerity with its matt black cover when laminating LP sleeves was the norm in Britain.

Nottamun Town’s narrative is mysterious. Still, that’s hardly a revelation. Its rhetorical contradictions and impossibles still captivate. It still communicates its otherworldliness. No wonder its Old Weird Europe tripped a switch in Dylan. From Jack Orion (Castle Music CMRCD304, 2001)

Ken Hunt’s obituary of Bert Jansch from The Independent of 6 October 2011 is to be found at http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/bert-jansch-guitarist-whose-style-influenced-his-peers-across-five-decades-2366017.html

Brother Ephus – Hedy West

This innocent, light-hearted banjo and vocal piece peopled with characters with names like Moses and Ephus is addressed to “revenant sisters”. It made its first appearance on Hedy West’s debut Topic album called Old Times & Hard Times – Ballads And Songs From The Appalachians (1965). She learnt this version of the song, which she attributed probably to minstrel song origins. It is full of fun with observations about such as angels’ footwear (“What kind of slippers do the angels wear?/Golden slippers to speed on air/They wear fine slippers and wear fine socks/And drop every nickel into the missionary’s box…”) and the trustworthiness of preachers (“Some folks say a preacher won’t steal/But I caught two in my water-melon field…/A-preachin’ and a-prayin’ and singin’ all the time/Snippin’ water-melons off the vine…”). From Ballads and Songs from the Appalachians (Fellside FECD241, 2011) More information at http://www.fellside.com/

Al Confini d’Ungheria – La Piva Dal Carner

Al Confini d’Ungheria – La Piva Dal Carner

In music everything starts from somewhere and nothing starts from nowhere – whether in alignment with, or opposition to what has gawn before. The Italian folk band B.E.V. (Bonifica Emiliano Veneta) alerted me to this remarkable album focussing on music from Emilla, the region way up north in Italy. It was part of their back pages, their roots and it was part of what they were carrying forward. Piva is an Italian term for bagpipes. Loving the buzz, advice taken, I back-tracked.

This still remains one of my very most played albums to emerge from the Italian Folk Revival. There is a floatiness and earthiness about what they play. Sky and earth. White and grey clouds. Greenery and reds – wine, that is. Everything here is drenched in a Northern Italian sensibility. It remains one of the finest tip-offs of my life.

“La pecora alla mattina bela e alla sera balla.” Or “The sheep bleats in the morning and dances in the evening.” What a metaphor for life! This music is like meeting a stranger on the road – a handsome man, a beautiful woman – needing to share a basket of bread, cheese and olives and a couple of bottles of cheeky reds begging to be uncorked, exhale and be enjoyed.

The band was Claudio Pesky Caroli on double-bass, vocals and piano, Walter Rizzo on French bagpipes – which the album misspells as Frech, German for ‘cheeky’, though that sounds fitting too -, Galician bagpipe, Renaissance shawm, Breton oboe, recorders and vocals, Paolo Simonazzi on hurdy-gurdy, two-row melodeon, vocals and spoons and Marco Mainini on vocals, soprano sax, clarinet and guitars.

This courting song’s title translates as ‘To Hungary’s border’ and harkens back to a time when Hungary – a personification of the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s sheer expanse – amounted to the limit of people’s imagination in terms of distance and separation. “Voglio andare tanto lontano, dagli amici e dai parenti/Voglio fare i miei lamenti, qualcheduno mi sposera…” The translation the notes give is, “I want to go very far away, from my friends and my relations/I want to make my lamentations, somebody will marry me…” I know that parenti looks like ‘parents’ but let’s steer clear because the region’s dialect does not obey Standard Italian rules. From La pegrà a la mateina, la bèla e a la stra labala – Canti e balli d’Emillia/Songs and dances from Emilia (Dunya 217506735 2, 1995)

More information at www.felmay.it and about Bonifica Emiliano Veneta at http://www.bonificaemilianaveneta.it/

Dark Star – Grateful Dead

The so-called Europe ’72 tour was probably the Dead’s finest sallying forth. They had an abundance of tip-top new compositions, a corpus of old and new work of a quality they would not surpass, only add to. It was also the last innings of Ron ‘Pigpen’ McKernan (organ, harmonica, percussion and lead vocals) who died in March 1973. He joined Jerry Garcia (electric guitars and vocals), Donna Jean Godchaux (vocals), Keith Godchaux (keyboards), Bill Kreutzmann (drums, percussion), Phil Lesh (electric bass guitar) and Bob Weir (rhythm electric guitar, vocals).

This version of their singular and signature voyage into new space is from the Bickershaw Festival in May 1972. They had so much to play for. It gets weepy at times but it soars and rides the up-draughts beautifully. From Europe’72 Vol. 2 (Grateful Dead Productions R2 528639, 2011)

More information about this and other releases from the 1972 European tour archives at http://www.dead.net/

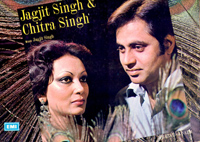

Aaye Hain Samjhane Log – Jagjit Singh & Chitra Singh

This LP must have been reissued many times over. This is the original vinyl version from the husband and wife duo that redefined ghazal (and nazm), in their case, the Urdu-language version of ghazal in particular. Neither had ghazal to the fore in their cultural backgrounds. Jagjit was born in Bikaner State, now modern-day Rajasthan of Sikh parents while his wife Chitra had been born in Bengal. There were only two duet tracks on this, their breakthrough LP. One finished each side of the album. This track concluded one of the most revolutionary albums in the history in Indian popular music. So much flows from this work. It was also the sound of sluice gates opening and if others failed to maintain standards, for the most part Jagjit Singh & Chitra Singh did. From The Unforgettables (Gramophone Company of India ECSD 2780, 1977)

This LP must have been reissued many times over. This is the original vinyl version from the husband and wife duo that redefined ghazal (and nazm), in their case, the Urdu-language version of ghazal in particular. Neither had ghazal to the fore in their cultural backgrounds. Jagjit was born in Bikaner State, now modern-day Rajasthan of Sikh parents while his wife Chitra had been born in Bengal. There were only two duet tracks on this, their breakthrough LP. One finished each side of the album. This track concluded one of the most revolutionary albums in the history in Indian popular music. So much flows from this work. It was also the sound of sluice gates opening and if others failed to maintain standards, for the most part Jagjit Singh & Chitra Singh did. From The Unforgettables (Gramophone Company of India ECSD 2780, 1977)

Ken Hunt’s obituary of Jagjit Singh from The Independent of 13 October 2011 is to be found at http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/jagjit-singh-singer-hailed-as-the-maestro-of-indian-ghazal-2369631.html

Don’t Ask Me Why – Laura Marling

To have a singer-songwriter to excite the imagination as much as Joni Mitchell prowling the earth is a very good thing indeed. Yes, Laura Marling’s been hailed another folk darling, especially given how she’s been taken to so many people’s bosoms. She is one of those musicians who summon images and memories of people before her while their voice sounds totally their own. The sound she makes is splendid. Plus, from reading a few interviews with her around the time of A Creature I Don’t Know‘s release I realise that there are currents and undercurrents to much of her material that are engaging. Just as I do when listening to Joni Mitchell or Jackson Browne or Judee Sill, I am willing to wait and have meaning imparted (or not). I mean that as high praise. From A Creature I Don’t Know (Virgin Records CDV3091, 2011)

To have a singer-songwriter to excite the imagination as much as Joni Mitchell prowling the earth is a very good thing indeed. Yes, Laura Marling’s been hailed another folk darling, especially given how she’s been taken to so many people’s bosoms. She is one of those musicians who summon images and memories of people before her while their voice sounds totally their own. The sound she makes is splendid. Plus, from reading a few interviews with her around the time of A Creature I Don’t Know‘s release I realise that there are currents and undercurrents to much of her material that are engaging. Just as I do when listening to Joni Mitchell or Jackson Browne or Judee Sill, I am willing to wait and have meaning imparted (or not). I mean that as high praise. From A Creature I Don’t Know (Virgin Records CDV3091, 2011)

What’s Going On – Marvin Gaye

Really, really tried to pin-point when the album or this track entered my life. It was recorded in May 1971. So for 40 years it has been part of the framework of my life. Still going strong. From What’s Going On (Motown 013 404-2, 2002)

Porcupine In November Sycamore – Rapunzel & Sedayne

As an opening flourish, this track is pretty damn good. The album notes say it’s “our old field holler in the Javanese Pelog mode, inspired by the North American Tree Porcupine in Blackpool Zoo…” Rapunzel & Sedayne recorded this album between January and February 2011. Some of Sedayne’s vocal phrasing carries of echoes of those who have gone before in the folk revival. To these ears, some of the stresses and glides in Blackwaterside sound Anne Briggs-like while True Thomas has a smack of June Tabor about it in its phrasing. Doesn’t matter one iota. Learn from the best and make what was theirs your own. Rapunzel & Sedayne keep a lot of air in their arrangements. I like that. From Songs From The Barley Temple (Folk Police FPR 001, 2011)

As an opening flourish, this track is pretty damn good. The album notes say it’s “our old field holler in the Javanese Pelog mode, inspired by the North American Tree Porcupine in Blackpool Zoo…” Rapunzel & Sedayne recorded this album between January and February 2011. Some of Sedayne’s vocal phrasing carries of echoes of those who have gone before in the folk revival. To these ears, some of the stresses and glides in Blackwaterside sound Anne Briggs-like while True Thomas has a smack of June Tabor about it in its phrasing. Doesn’t matter one iota. Learn from the best and make what was theirs your own. Rapunzel & Sedayne keep a lot of air in their arrangements. I like that. From Songs From The Barley Temple (Folk Police FPR 001, 2011)

More information at http://www.folkpolicerecordings.com/rapunzel–sedayne.html

When A Guy Gets Boobs – David Lindley y Wally Ingram

People develop strategies, diversions or bad habits before hitting the microphone. This one’s not big, it’s not clever but a few years back I start singing this John Lee Hooker-mated-with-Woody Allen song of David Lindley’s before going on stage. Now I’m not given to singing in public but greeting the public with a smile is no bad thing.

It begins, “When a guy gets boobs it don’t look so good…” – something few would deny – and it just takes off and descends into a world of lardy butts, giant donuts, burgers and fries, blood vessels a-clogging and bits a-drooping. It was recorded somewhere in Europe in 2003. It works for me, oh yes. From Live! (no name, no number, 2004) http://www.davidlindley.com/

Rāg Durgā – Ali Akbar Khan

Rāg Durgā – Ali Akbar Khan

No apologies for the inclusion of another track from this album after October’s Rāg Hemant. It’s a priceless album and a combination of artistic wellspring and whirlpool and culturally the deepest of musical pools to dive into.

Durga is the embodiment of divine female strength. The Goddess Durgā is generally depicted riding a tigress or lioness. From Indian Architexture (Water Lily Acoustics WLA-ES-20-SACD, 2001)

For more information about Water Lily Acoustics visit http://waterlilyacoustics.com/main.htm

The image of the Durgā mandir (temple) in Jalandhar at night is © Santosh Sidhu/Swing 51 Archives. The copyright of all other images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers.

1. 11. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] There are many reasons for pulling faces and putting on accents. And Dudley Moore excelled in doing both. In this hour-long, black-and-white, Australian Broadcasting Corporation show, first shown in 1971, Moore runs through a gamut of facial contortions and thespian gazes and a range of ‘his voices’. He brings his Pete & Dud voice – reminding that even when continents separated them physically, Peter Cook was beside him in spirit – to the piano.

[by Ken Hunt, London] There are many reasons for pulling faces and putting on accents. And Dudley Moore excelled in doing both. In this hour-long, black-and-white, Australian Broadcasting Corporation show, first shown in 1971, Moore runs through a gamut of facial contortions and thespian gazes and a range of ‘his voices’. He brings his Pete & Dud voice – reminding that even when continents separated them physically, Peter Cook was beside him in spirit – to the piano.

He subjects material such as his own hamming-about novelty Madrigal, the souped-up Lieder duet of Die Flabbergast and, naturally, his and Cook’s valedictory song Goodbyee to various forms of falsetto screech. Revealingly (for cub psychoanalysts in the readership) he adopts somebody else’s voice in the spoken introduction to his first-rate composition ‘Chimes’. Always a good distancing gambit, psychologically speaking.

Frequently with music DVDs any CD audio-counterpart is little more than a cheapo bonus duplication. In the case of Jazz in “Oz” the CD generally allows the listener to filter out Moore’s visual distractions to concenhtrate on the music. For example, from the laughter that ripples through the Saint-Saëns/Moore The Swan the ‘blindfolded viewer’ knows that there’s a whole lotta muggin’ goin’ on. Setting aside the matter of hilarities – and the humour is way removed from jazz-bo’ comics – the trio’s jazz, for example, on Strictly For The Birds, is definitely of the era. While Moore, Pete Morgan on double-bass and Chris Karan on kit drums dip into the Great American Songbook on The More I See You, Moon River and The Look of Love – and shine on their lustrous melodies – what emerges is the strength of Moore’s own jazz-veined compositions. A prime example is Chimes. Once the comicality of the visual introduction is stripped out, you know he isn’t playing it for laughs. The two versions combine like the accounts of witnesses who saw something from different vantage points. Both show what editing and angles can add or subtract.

A very British, period artefact.

Jazz in “Oz” Martine Avenue Productions MAPI – 2665 (DVD and CD set), 2008

More information at the official Dudley Moore website: www.martineavenue.com

17. 10. 2011 |

read more...

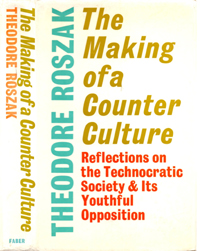

[by Ken Hunt, London] Let’s start metaphorical. Maybe poetical and ecological too. Counter-culture in the 1960s was like alternative now, like spring-water welling to the surface and forming rivulets. Streams and rivers form, few with fixed shapes. Currents change unpredictably. Some silt or dry up or form ox-bow lakes. Others keep on flowing and joining up. Counter-culture and alternative have something else going for them. Without getting rheumy-eyed, it’s like great river junction at Prayaga – Hinduism’s Allahabad – where the Ganges and Jamuna meet the invisible Sarasvati. Like Prayaga, they are where the seen and the spiritual meet in a great confluence.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Let’s start metaphorical. Maybe poetical and ecological too. Counter-culture in the 1960s was like alternative now, like spring-water welling to the surface and forming rivulets. Streams and rivers form, few with fixed shapes. Currents change unpredictably. Some silt or dry up or form ox-bow lakes. Others keep on flowing and joining up. Counter-culture and alternative have something else going for them. Without getting rheumy-eyed, it’s like great river junction at Prayaga – Hinduism’s Allahabad – where the Ganges and Jamuna meet the invisible Sarasvati. Like Prayaga, they are where the seen and the spiritual meet in a great confluence.

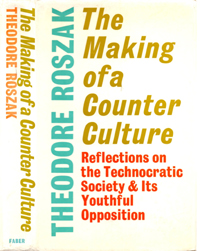

Theodore Roszak’s 1969 book The Making of a Counter Culture – Reflections on the Technocratic Society & Its Youthful Opposition was the first major attempt to examine and contextualise the movement and, importantly, its historical continuum. At one point he observes how, “Shelley’s magnificent essay ‘The Defence of Poetry’ could still stand muster as a counter cultural manifesto.” Counter-culture had everything to do with what Patti Smith calls “chosen ancestors”. Percy Bysshe Shelley is still a chosen ancestor, waiting in the wings to come on. The first time I met Ginsberg he was returning from a visit to a Southern English place with William Blake associations. The last time we met he gave an impromptu performance of Shelley’s poem The Mask of Anarchy; it was so gloriously approximate, it amounted to a rewrite. When it comes to choosing ancestors, wit lies in not in fabricating genealogy but what you do with the legacy.

Historically, personal recommendation was the main way of tuning in and turning on to new experiences. Through word of mouth, reading and listening you made connections. In that pre-internet age, it was linking finding a rope at night. It was only come daylight that you started to get a proper feel for how far back it stretched and how varicoloured the rope’s strands were. Nowadays it’s easier and more difficult. Once the difficulty was accessing information. Now, it’s information overload. Although a title like Sketches of American Counterculture requires a New World focal point, bear in mind that rope stretched right round the globe.

So you read Kerouac and he connects with Ginsberg, Corso, Ferlinghetti, Burroughs and Slim Gaillard. You discover Bob Dylan and you see the names Eric von Schmidt and Martin Carthy on the backs of LPs. More recommendations. Avant-garde composers John Cage and Lou Harrison steer you to Colin McPhee, Henry Cowell and Philip Glass. Or you discover Alla Rakha and Ravi Shankar and get to Glass by a non-minimalist route. There are many routes. (Shankar’s original overseas audiences came via Satyajit Ray’s films and the jazz and folk scenes before the Beatles.) Eventually you have a countercultural rope trick.

You join up the microdots and the connections are infinite. Steve Reich, Pauline Oliveros, the Grateful Dead, Country Joe and the Fish all have connections with the San Francisco Mime Troupe. Likewise, Burroughs connects with Laurie Anderson, David Bowie, Paul Bowles, Lou Reed and on and on and back to Patti Smith’s “chosen ancestors. Or to digress outside the arts, in 1962 you read Rachel Carson’s environmental wake-up call about the agrochemical impact on the food chain, Silent Spring and that leads to further alternative discoveries about what food you are eating and to organic gardening, ecology and the environment. These Sketches focus on the arts, but when did you last meet anyone artistic who doesn’t eat?

Counter-culture’s great confluence of ideas bust open many a mind-dam. Yet, as citing Shelley suggests, it never sprang fully formed. It came with historical forebears. It drew on earlier bohemian, artistic and radical antecedents. It built on dissenting, freethinking traditions. It suggested political, belief system or humanist ethics. It even responded to mainstream society legalising the forbidden or redefining the rules. North America may have its well-known traditions of polygamy or polyamory but so did Germany. Had history lessons about the 30 Years War recalled the Church’s injunction to good god-fearing Germans to take 10 wives in order to repopulate congregations, I might have paid more heed. Mind you, you were probably never taught about the English Revolution with its radical organisations like the Levellers, Ranters and Diggers – resurrected in San Francisco in the 1960s – or British republicans celebrating 30 January 1649. So we’re quits.

What I remember best – or choose to remember the most – is the Counter-culture’s open-mindedness, its invitation to examine conformities and expand minds. Of course, it had hedonistic moments and peddled derangements of the mind. (They weren’t all bad either.) It’s just such a pity the Counter-culture got saddled with such a shitty name. The dead hand of etymology weighs it down. Unlike the old Johnny Mercer and Harold Arlen lyric, counter-culture accentuates the negative with its ‘contra’ and ‘against’ associations. When counter-culture entered everyday speech in the 1960s, it was laden with all manner of negative baggage. On balance, its positivity outweighed the negative. The movement itself was more pro than anti. Alternative accentuates the positive better. Anyway, I’m still finding new chosen countercultural ancestors. Or getting to know them better. I suspect the day I stop I’ll be dead.

This is a version of a German-language essay published in the programme to TFF Rudolstadt in 2007. This essay is published here for the first time in English in memory of Theodore Roszak (1933-2011).

17. 10. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Lovin’ Spoonful was a band that, in the most cool of manners, took its name from a Mississippi John Hurt recording. They made a music that brought together jug band (skiffle) music, folk and folk-blues with an added pop into rock sensibility around 1966 when nobody knew exactly what was going on and definitely nobody knew where it was all going to go.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Lovin’ Spoonful was a band that, in the most cool of manners, took its name from a Mississippi John Hurt recording. They made a music that brought together jug band (skiffle) music, folk and folk-blues with an added pop into rock sensibility around 1966 when nobody knew exactly what was going on and definitely nobody knew where it was all going to go.

Born in Toronto on 19 December 1944, Zalman ‘Zal’ or ‘Zally’ Yanovsky (bottom left on the album sleeve in yellow and orange stripes, next to John Sebastian’s orange and white stripes) died days short of his 57th birthday on 13 December 2002. Arriving on the Eastern seaboard of Canada’s southern neighbour with a trio called the Halifax Three – its Halifax, Nova Scotia-born Dennis Doherty subsequently went on to well for himself in The Mamas and The Papas – Yanovsky made contacts that in New York found him and Doherty joining the Mugwumps. That group was name-checked in the Mamas And The Papas’ potted history of folk into rock, Creeque Alley – a baton of an autobiographical history that the Grateful Dead’s Truckin’ took up and ran with.

“The Mugwumps didn’t make many records,” wrote Michelle Phillips in her autobiography, California Dreaming – The True Story of The Mamas And The Papas (1998), “but they became legendary after they had broken up. They were a cult after the event.” Keeping careful-with-the-‘legendary’-axe, St. Eugene (British Columbia) business the crowd’s comings and goings enabled them to be a backbone of a Pete Frame rock family tree.

Yanovsky joined the Lovin’ Spoonful and became intrinsic to its succession of local, then national, then international hits. Those hits included Do You Believe In Magic, Daydream and Summer In The City. Those songs were as other and distinctive as anything that the Rolling Stones, The Kinks or the Small Faces were releasing in Britain. They shone out.

Everything was going so well… Then in 1966 with Summer In The City roaring up the charts internationally, Yanovsky and Steve Boone found themselves in a bit of a quandary. They got busted in San Francisco for possession of marijuana – it was still illegal in California back then. (May still be.)

Pressure was applied. Fearful of visa problems, they sang. “The episode,” observed Joel Selvin in Summer of Love (1994), “finished the Spoonful in underground circles.” Back then even if we didn’t know the exact detail, there was enough scurrilous stuff flying around to glean that all was not right in the state of the Spoonful. Mud stuck.

Post-Spoonful Yanovsky played with Kris Kristofferson – I saw him at the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival – and he made a cameo appearance in Paul Simon’s One Trick Pony (1980). At the time of his death, he was a restaurateur in Kingston, Ontario in a place wittily called Chez Piggy.

For more information about Frame and his Rock Trees – visit http://blog.familyofrock.com/

10. 10. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, Gaienhofen am Bodensee] Purposeful drifting might conjure images of lying on a lilo – one of those air mattresses – on a lake, floating where the breeze, current or tide take you but that would be well wrong, John. These driftings all link up, even if the connections may not cry out. Ten selections from the Bosnian vocalist Amira, the Welsh group Fernhill, the largely forgotten British faux-folk slash singer-songwriter Mick Softley, the never-to-be-forgotten singer and guitarist Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, the maestro of Hindustani maestros Ali Akbar Khan, the Karnatic vina maestro Balachander, the koto player Nakahsahi Gyōmu, the Kinks who turned office workers into heroes of the everyday, Cilla Fisher and Artie Trezise, the Gaelic singer Alyth McCormack… Louring over this batch of music and jumble of emotions was the death of Ray Fisher balanced with the consolation of time spent with dear friends at Lake Constance (Bodensee) and an overdue reunion with Hermann Hesse.

[by Ken Hunt, Gaienhofen am Bodensee] Purposeful drifting might conjure images of lying on a lilo – one of those air mattresses – on a lake, floating where the breeze, current or tide take you but that would be well wrong, John. These driftings all link up, even if the connections may not cry out. Ten selections from the Bosnian vocalist Amira, the Welsh group Fernhill, the largely forgotten British faux-folk slash singer-songwriter Mick Softley, the never-to-be-forgotten singer and guitarist Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, the maestro of Hindustani maestros Ali Akbar Khan, the Karnatic vina maestro Balachander, the koto player Nakahsahi Gyōmu, the Kinks who turned office workers into heroes of the everyday, Cilla Fisher and Artie Trezise, the Gaelic singer Alyth McCormack… Louring over this batch of music and jumble of emotions was the death of Ray Fisher balanced with the consolation of time spent with dear friends at Lake Constance (Bodensee) and an overdue reunion with Hermann Hesse.

Oj Ti Momče Ohrigjanče – Amira

Amira Medunjanin really entered my field of vision with her London concert debut supporting Taraf de Haïdouks in June 2007. Petr Dorůžka and I, your genial hosts here, went to the concert together. At that point the only recording of hers that I knew was Amira’s first album, Rosa (2004). Seeing her live enabled me to make greater sense of what she was doing. Since then, Amira’s progress has been a wonder to behold.

Amira Medunjanin really entered my field of vision with her London concert debut supporting Taraf de Haïdouks in June 2007. Petr Dorůžka and I, your genial hosts here, went to the concert together. At that point the only recording of hers that I knew was Amira’s first album, Rosa (2004). Seeing her live enabled me to make greater sense of what she was doing. Since then, Amira’s progress has been a wonder to behold.

On this splendid track, a Macedonian song of grief from a man’s point of view, from her fourth album, Amulette she is joined by Bojan Z (Zulfikarpašić) on piano, Nenad Vasilić on string bass, Bachar Khalife on percussion with guest Vlatko Stefanovski on guitar. The vibe is Macedonian folk-jazz. The notes say, “This time the sorrow of loneliness and yearning belongs to a man. He walks by the lake and cries for his loved one. ‘Come back to me, here by the lake I await you.'” The separation could be the aftermath of an affair, a broken relationship or a bereavement. You get the drift. From Amulette (World Village 450018, 2011)

For more information visit www.amira.com.ba

Diddan – Fernhill

There are many exhilarating things to say about Fernhill’s work. Their music speaks to me even though nearly all of the little Welsh I ever had long ago slipped away through lack of use and practice. Nevertheless, there is something about the language’s sound that continually draws me back. Without entering the misty realm of cliché, it is a language of musicality with the sort of gruff, guttural leanings that contrast so well.

Fernhill is Christine Cooper (fiddle, voice), Tomos Williams (trumpet, flugelhorn), Ceri Rhys Matthews (guitar, flute, voice) and Julie Murphy (voice, sruti). Canu Rhydd (‘free poetry’), the minimalist album notes tell, was recorded in the last days of the Dartington College of Arts “before the college left its Devon home for good”. To my mind, Diddan’s style of arrangement – sweeping one moment, intimate the next – crystallises so much about Fernhill that engages so much. It captures their energy so very, very well with Julie Murphy’s soaring over driving fiddle underpinned with understated brass and guitar.

For those more inclined to the English, Forest – their take on the carol also known as Down In Yon Forest or the Corpus Christi Carol with the recurring lines “The bells of Paradise I heard them ring/…/And I love my Lord Jesus above any thing”- is also superb. From Canu Rhydd (Disgyfrith CD02, 2011)

For more on the history of Dartington Hall, track down Victor Bonham-Carter’s Dartington Hall – The History of an Experiment (Phoenix House, London, 1958)

More information about Fernhill at www.fernhill.info

Love Colours – Mick Softley

Back in 1971 Pete Frame interviewed Mick Softley for Zig Zag, the magazine that counts as one of turning-points in the appreciation of what was going on musically in Britain (and elsewhere) at the time. At times it was like a divining rod. Parts of Frame’s interview are included in the notes to this release of Softley’s Sunrise (1970) and Street Singer (1971). Another old friend, Nigel Cross, founding editor of Bucketfull of Brains supplies the contextual essay that accompanies the rest of this package.

Mick Softley had seen a small measure of success when his colleague Donovan covered his Gold Watch Blues on his debut LP and The War Drags On on the EP The Universal Soldier. As Nigel Cross reminds, both got into the UK Top Ten. Softley and Mac MacGann were going to go on tour with Donovan as part of his backing band and got as far as the Isle of Skye – not a sign of no sense of direction, more to do with it being Donovan’s home – but it never happened and they returned to St. Albans. Softley and MacLeod parted ways and Softley went solo.

Parenthetically, Mac MacGann went on to marry the US expatriate singer Dorris Henderson (how many times must she have been asked about the story of her singing on that wonderful Lord Buckley album?) and made loads of local music in Middlesex and Surrey, and settled in the Ealing-Richmond-Isleworth triangle; he died in Isleworth in 2011, by which time he and I had ample opportunities to talk about the flora and the fauna, especially the birdlife, of the upper tidal Thames and its environs.

Love Colours is an Indian-inflected, impressionistic piece from Sunrise with Lyn Dobson on sitar, Ned Balen on and tabla and Chris Lawrence on bass. Sue and Sunny (Wheatman), Lesley Duncan and Gringo add backing vocals. Very much in the stamp of the times, it just keeps growing. Pentangle’s Tony Cox produced. From Sunrise/Street Singer (BGO Records BGOCD66O, 2005)

Phil Davison’s obituary ‘Mac McGann: Folk musician in the vanguard of the singer-songwriter movement’ is worth reading at http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/mac-mcgann-folk-musi cian-in-the-vanguard-of-the-singersongwriter-movement-2264847.htm

Mo Run An Diugh Mar an De Thu (Hi Horó ’S Na Hòro Eile) – Alyth McCormack

Mo Run An Diugh Mar an De Thu (Hi Horó ’S Na Hòro Eile) – Alyth McCormack

This is from an album by Jonny Hardie (fiddle and guitar), Brian MacAlpine (piano and keyboards), Alyth McCormack (vocals) and Rory Campbell (pipes, whistles and vocals) and grew out of a commission by the Highland Festival, the notes say, for a programme of music celebrating Captain Simon Fraser’s Airs and Melodies peculiar to the Highlands of Scotland and the Isles of 1816. Fraser (1773-1852) had had Nathaniel Gow as his violin teacher and Gow’s sensibilities must have coloured his approach when laying down this collection’s tunes, many taken from the singing of his father and grandfather. However, such was the political climate of the day that he felt it politic to omit the words.

Nevertheless, the collection sold out. In an ill-starred move he recycled the profits into republishing the book in India and the American colonies. He fell foul of knavery. A portent of illegal downloading – and a reminder that things keep coming around – his book had already been pirated in the colonies and his printing failed to recoup his outlay.

This song – it translates as ‘My love today as heretofore’ – reunites the words with a melody that is seared into my cranium. It is the tune, the slow air wedded to Robert Burns’ Ae Fond Kiss (for example, on Eddi Reader’s sublime Sings The Songs of Robert Burns (Rough Trade, 2003)). Alyth McCormack sings this song so beautifully, bringing out its pathos. She returned to the song, its title shortened to Hi Horó, on her solo album An lomall/The Edge (Vertical, 2000) with beats and a greater rhythmicality.

If even a handful of listeners or visitors to this site back-track to the earlier Captain’s Collection version it would make an already happy man happier still. Either way, Alyth McCormack is a most marvellous talent championing the Gaelic arts. From The Captain’s Collection (Greentrax CDTRAX 187, 1999)

More information at http://www.greentrax.com/ and http://alyth.net/

Connection – Ramblin’ Jack Elliott

Originally released in 1968 on Reprise, Young Brigham was Ramblin’ Jack’s debut album for a major label. This Jagger/Richards song first appeared on the Stones’ Between The Buttons and would prove to be a song that he really took to heart and would regularly revisit. From Young Brigham (Collector’s Choice Music CCM-198-2, 2001)

Raagam-Taanam-Pallavi in Shri – S. Balachander

Raagam-Taanam-Pallavi in Shri – S. Balachander

Balachander was a knotty character who rarely shied away from musical unconventionality. He could have been written off as an iconoclast or a renegade but for one thing. Balachander possessed a musicality that his critics could only envy. In South Indian music, it is the norm for a ragam to receive a short, crisp exposition, although there is a sparingly deployed sequence comparable to the longer renditions familiar from Hindustani concerts. That is called a raagam-taanam-pallavi. From Veena Chakravarthy S. Balachander In Concert (Swathi’s Sanskriti SA138, 2010)

Rokudan – Nakahsahi Gyōmu

A solo koto piece that swells and develops so beautifully through a set of variations from the third volume of the 1941 KBS recordings that World Arbiter has released. I know nothing about Nakahsahi Gyōmu – and never went googling – but to these ears he has a fine touch to the koto in a gagaku setting, gagaku being a courtly music style placing great weight on not only the notes but also the spaces surrounding them. A note therefore is not only released but framed. Rather than cramming in notes, the musician liberates the notes so each can be, as it were, held up to the light and their facets examined before the next arrives. Of course, that doesn’t always happen. A flurry may deliver a package of notes, so to speak. From Japan: Koto – Shamisen – 1941 (World Arbiter 2012, 2011)

Waterloo Sunset – The Kinks

It’s not just one of those songs, it’s one of those perfect London songs. From Something Else By The Kinks (Universal/Sanctuary 273 214-1, 2011)

For more information about this song, track down Nick Hasted’s You Really Got Me: The Story of The Kinks (Omnibus Press, 2011) and his highly recommended taster article ‘Ray Davies – How a lonely Londoner created one of the great Sixties songs’ from The Independent of 26 August 2011: http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/features/ra y-davies–how-a-lonely-londoner-created-one-of-the-great-sixties- songs-2343826.html

Fisher Lassies – Cilla Fisher and Artie Trezise