Articles

[by Ken Hunt, London] Now, it’s only personal opinion. Still, hear out my theory. Every movement has its share of before-and-after benchmarks or epiphanies. They divide people who experienced them first-hand from those who got the experience passed down. On 1 June 1980, a date that shall forever remain hallowed in the annals of what we laughingly call England’s Folk Revival, Topic Records released a twelve-inch, nine-track masterwork known as 12TS411 in the trade and as Penguin Eggs to the punters that snaffled it up. It is no exaggeration to say that it took the folk scene by storm, much as Dick Gaughan’s Handful of Earth did the following year. The auteur of this cinematic masterpiece – certainly the songs he sang ran movies in my skull – was a 33-year-old guitarist and folksong interpreter called Nic Jones.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Now, it’s only personal opinion. Still, hear out my theory. Every movement has its share of before-and-after benchmarks or epiphanies. They divide people who experienced them first-hand from those who got the experience passed down. On 1 June 1980, a date that shall forever remain hallowed in the annals of what we laughingly call England’s Folk Revival, Topic Records released a twelve-inch, nine-track masterwork known as 12TS411 in the trade and as Penguin Eggs to the punters that snaffled it up. It is no exaggeration to say that it took the folk scene by storm, much as Dick Gaughan’s Handful of Earth did the following year. The auteur of this cinematic masterpiece – certainly the songs he sang ran movies in my skull – was a 33-year-old guitarist and folksong interpreter called Nic Jones.

A since-defunct weekly music magazine called Melody Maker voted Penguin Eggs its 1980 Folk Album of the Year. In February 1982 Jones sustained near-fatal injuries in a car crash. Anyone who saw him play before the accident – and I did – is forever divided from those who never saw him perform in his heyday. No elitism intended: that is the simple nature of things. There are many people I would have loved to have witnessed perform first-hand and/or interviewed to capture the stories they could tell. That’s life.

I never saw The Halliard – Nic Jones, Dave Moran and Nigel Paterson – perform live. They preceded his time as a solo artist. The songs that this group worked up however, travelled ahead of them. They “began to have a life of their own,” as Dave Moran recalls in this songbook’s main historical essay, snappily entitled A Short Historie of The Halliard. At one gig, he recalls, though printed words, like email emoticons, lack the ability to communicate miffed properly, the residents devoted their first set to Halliard material. The Halliard recovered to deliver a different set, only to have the club organiser tell them to “include the songs just sung by our residents in your second set after the break as they are club favourites.” Robbed of your own repertoire! The club favourites and beyond that you get to here include British Man of War, Billy Don’t You Cry For Me, Stow Brow, Calico Printer’s Clerk and Going For A Soldier, Jenny.

Judging by this book and the music currently available on CD, I wish I had had the chance to see The Halliard between 1964 and 1968 when, as Nigel Paterson explains they were touring “almost nonstop…as full-time professionals.”

Nic Jones, Dave Moran & Nigel Paterson – Broadside Songs of the Halliard Mollie Music MMSB-1 (2005, reissued without CD 2006)

For more information visit, http://www.nicjones.net/ and http://nigelpatersonmusic.com/

26. 9. 2011 |

read more...

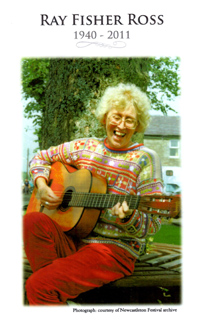

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Scottish folksinger Ray Fisher once told me that she had a series of scheduled performances in Czechoslovakia that were abruptly cancelled when the Soviet bloc forces had the bad manners to invade in 1968. The following year, rescheduled concerts finally took place. She recalled the mayor of one town greeting her. Two Soviet officers flanked him. The mood was tense. Then, one of them broke the ice by asking her excitedly whether she knew the Beatles. (With her winsome charm, no doubt she pulled it off effortlessly but alas I have no memory of how exactly she got out of that one.) As part of the cultural exchange, the tour introduced her to dudy – Czech bagpipes and ‘bagpipes’ in Czech – and she remembered the experience with wry fondness.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Scottish folksinger Ray Fisher once told me that she had a series of scheduled performances in Czechoslovakia that were abruptly cancelled when the Soviet bloc forces had the bad manners to invade in 1968. The following year, rescheduled concerts finally took place. She recalled the mayor of one town greeting her. Two Soviet officers flanked him. The mood was tense. Then, one of them broke the ice by asking her excitedly whether she knew the Beatles. (With her winsome charm, no doubt she pulled it off effortlessly but alas I have no memory of how exactly she got out of that one.) As part of the cultural exchange, the tour introduced her to dudy – Czech bagpipes and ‘bagpipes’ in Czech – and she remembered the experience with wry fondness.

Born in Glasgow, Scotland on 26 November 1940, in 1962, she had married Colin Ross, the fiddler and piper, and later co-founder of the High Level Ranters, and settled in Tyneside. With her marriage to Colin, she was wed – or, as she sometimes joked – widowed to the pipes. She was one of six daughters – Jean, Joyce, Cindy, Audrey and Priscilla – and one token son – Archie – born into a family with catholic musical tastes that included light operatic and parlour fare (their father John Galbraith Fisher sang in the City of Glasgow police choir), Scots and, since their mother, Marion née MacDonald (known as Morag or Ma Fisher) had it as her mother tongue, Gaelic songs. Like many folkies of her generation, Britain’s skiffle movement was the springboard to a greater awareness of folk music. Through a fluke of fate and proximity, a bloke who owned a local record shop lent US import LPs on Folkways by Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, Buell Kazee and Aunt Samantha Bumgarner to Hamish Imlach, whose Cod Liver Oil and The Orange Juice – Reminiscences of a Fat Folk Singer – discusses the early Glasgow folk scene. Imlach borrowed them because he was the one with a record player that could play them.

Born in Glasgow, Scotland on 26 November 1940, in 1962, she had married Colin Ross, the fiddler and piper, and later co-founder of the High Level Ranters, and settled in Tyneside. With her marriage to Colin, she was wed – or, as she sometimes joked – widowed to the pipes. She was one of six daughters – Jean, Joyce, Cindy, Audrey and Priscilla – and one token son – Archie – born into a family with catholic musical tastes that included light operatic and parlour fare (their father John Galbraith Fisher sang in the City of Glasgow police choir), Scots and, since their mother, Marion née MacDonald (known as Morag or Ma Fisher) had it as her mother tongue, Gaelic songs. Like many folkies of her generation, Britain’s skiffle movement was the springboard to a greater awareness of folk music. Through a fluke of fate and proximity, a bloke who owned a local record shop lent US import LPs on Folkways by Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, Buell Kazee and Aunt Samantha Bumgarner to Hamish Imlach, whose Cod Liver Oil and The Orange Juice – Reminiscences of a Fat Folk Singer – discusses the early Glasgow folk scene. Imlach borrowed them because he was the one with a record player that could play them.

Recorded music, like these Folkways LPs and the Weavers, fed the heads of Archie, Bobby Campbell and Ray informing their skiffle group’s repertoire. “It was really through Archie,” she told Howard Glasser in an interview for Sing Out! in 1974 (Volume 22/number 6), “that I first started singing. Archie and I and Bobby Campbell went to the same school. Bobby played violin in the school orchestra. At the time in Glasgow there were lots of skiffle groups, and Archie and Bobby decided they were going to start a group.” The Wayfarers would open for Pete Seeger in Glasgow, Edinburgh and Aberdeen. And that was no small deal.

Ray also studied with the Scottish Traveller ballad singer, Jeannie Robertson, spending her school summer holidays in her finals year and learning from her . It was an extraordinarily brave thing to do. It flew in the face of convention since many viewed Travellers with suspicion. By staying at Robertson’s home in Aberdeen, she dismissed prejudices and warinesses about the Traveller community. Over those six weeks, she imbibed open-mindedly. When she left, she understood. It was one of the experiences that turned her into one of Scotland’s finest interpreters of folk material. She heard Jeannie Robertson, later, in 1968, to be appointed MBE for her services to traditional music, sing not only the big ballads but also the radio hits of the day whilst doing the washing up. Ray Fisher never unlearned those lessons.

Ray and Archie Fisher formed a duo which lasted until 1962 when she moved to Tyneside. Archie recalled at Ray’s funeral that living in two different cities meant that they had little chance to rehearse for their appearances. Rehearsing was quite important as the duo was appearing on the Scottish television teatime magazine programme, Here And Now. Actually, very important, as they were going out live. Since his financial position was weaker, he would reverse the charges (call collect for North American readers) and they would rehearse for their broadcasts over the phone. Camouflaging the extent of their under-rehearsal on screen they would look directly into each other’s eyes. This look is captured well in one famous image from Brian Shuel’s portfolio of photographs. One important reason for looking so intently at each other is that they were lip-reading as well in order to get the lyrics right. The duo’s EP Far Over The Forth EP (Topic, 1961) captures the period and the folkier side of their repertoire well but in the television studio they were also running through an output of topical songs in the style of the day, many of which were learnt for the transmission and then forgotten. Far Over The Forth Scots had an unabashed Scottish focus and regionality, something that would take on a greater significance in future years. Both Dick Gaughan and Anne Briggs took direction from it.

Singing for Labour Party events, Centre 42 concert parties, pro-CND, anti-Polaris protests and Aldermaston marches brought Ray further into left-wing political circles. In the period between 1963 and 1965, she contributed to three important projects and a handful of ‘various artists’ projects, notably the fake Edinburgh Folk Festival anthologies (actually recorded specifically for Decca in a studio ‘re-creation’ of the festival experience). The first was A.L. Lloyd’s The Iron Muse. This was, Bert Lloyd explained in the LP notes, an album of industrial songs. “‘What is folk song?’ he asked as his opening rhetorical flourish. “The term is vague and seems to be getting vaguer. However, the songs on this record may conveniently be called ‘industrial folk songs’ for without exception they were created by industrial workers out of their own daily experience and were circulated, mainly by word of mouth, to be used by the songmakers’ workmates in mines, mills and foundries.” Both Ray and her husband Colin contributed to this project, as they did to the sixth On The Edge radio ballad, a form of audio-documentary with song, devised and developed by Ewan MacColl, Charles Parker and Peggy Seeger for BBC radio. First broadcast in February 1963, it addressed the transition from childhood to adolescence to adulthood. (First released on LP on the Argo label in 1967, it was reissued as a Topic CD (Topic TSCD 806) in 1999 as part of Topic’s radio ballad release programme.)

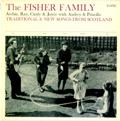

Most important of all, many would consider, was Topic’s LP The Fisher Family, recorded in 1965 and released the following year. Its subtitle said ‘Traditional and New Songs from Scotland’. Bill Leader recorded it at the Fisher Family palace, while Joe Boyd, his assistant on the job (later to achieve other things through Witchseason, Island, Elektra, Reprise and more, but also the snapper that captured the cover image), slept in the car outside because there was no more room in the palace. At her funeral, her surviving sisters sang Ewan MacColl’s Come All Ye Fisher Lasses, the album’s opening track on which Ray had sung lead.

Most important of all, many would consider, was Topic’s LP The Fisher Family, recorded in 1965 and released the following year. Its subtitle said ‘Traditional and New Songs from Scotland’. Bill Leader recorded it at the Fisher Family palace, while Joe Boyd, his assistant on the job (later to achieve other things through Witchseason, Island, Elektra, Reprise and more, but also the snapper that captured the cover image), slept in the car outside because there was no more room in the palace. At her funeral, her surviving sisters sang Ewan MacColl’s Come All Ye Fisher Lasses, the album’s opening track on which Ray had sung lead.

A short digression. The tail end of Cyclone Katia was still blowing the day of the funeral – 12 September 2011 – and trains down to London were delayed more than somewhat by fallen trees. When we reached London, a disparate band of stranded travellers arrived to missed connections and last trains gone. The rail company laid on taxis and bundled people with nearby destinations off together. Finding common cause in adversity, we chatted and a Scottish woman talked about missing her friend’s wedding because of rail staff misdirecting on to a train, the first stop turned out to be the wrong side of the border, Newcastle upon Tyne. She spoke of crying uncontrollably and MacColl’s words “greet like a wean” (‘weep like a child’) from Come All Ye Fisher Lasses came back to me. After hearing them an English voice use those words, she repeated them in half-surprise and burst into laughter.

Ray expressed little interest in recording, being averse to the regime of recording studios and much preferring the spontaneity of singing to living, breathing humans or delivering something live, say, to radio. Never partial to the studio recording process, she successfully managed to manoeuvre in the most eel-like of ways and succeeded in putting off recording her debut solo debut, The Bonny Birdie (Trailer, 1972) into the next decade. This was a feat in itself. Again recorded by Bill Leader (with Seumas Ewens assisting), its producer Ashley Hutchings brought in a bunch of musicians to re-upholster the arrangements with Martin Carthy, Tim Hart and Peter Knight and Hutchings himself from the Steeleye Span circle, Alistair Anderson and Colin Ross by then members of the High Level Ranters, Bobby Campbell (long past his Wayfarers days) and Liz and Stefan Sobell. Typical of her dry wit, she explained of The Forfar Sodger (The Forfar Soldier) that, “To hirple means to hobble (as if you didn’t know!)” The album was later reissued by Highway Records and still later fell foul of the contractual conundrums presented by the demise of Bill Leader’s Leader and Trailer labels. Ten years later she made her second album Willie’s Lady (Folk-Legacy, 1982). Less florid, more natural than The Bonny Birdie, it felt closer to her live act – not that records any longer needed to be mere reflections of concert performance or a folk club repertoire. Its magnificent title track, a slow build-up of accumulated repetitions from a pre-televisual age, appeared six years after Martin Carthy’s version on Crown of Horn (Topic, 1976). In fact, they had cracked their individual versions – hers in Scots, his in English – the same night when Carthy stayed with the Rosses in Monkseaton. Another highlight was the closing track, her treatment of Alan Rogerson’s version of When Fortune Turns The Wheel – a song she had learned from Lou Killen. Between those two songs you discover what made her unique as a singer and song interpreter.

In 1991 she released her third and final solo album Traditional Songs of Scotland which complemented Saydisc’s English and Welsh companion volumes – Jo Freya’s Traditional Songs of England and Siwsann George’s Traditional Songs of Wales/Caneuon Traddodiadol Cymru. Its out-take Now Westlin’ Winds, with Martin Carthy accompanying on guitar, from the same sessions appeared on the seasonal round anthology, All Through The Year (Fledg’ling, 1991).

In 1991 she released her third and final solo album Traditional Songs of Scotland which complemented Saydisc’s English and Welsh companion volumes – Jo Freya’s Traditional Songs of England and Siwsann George’s Traditional Songs of Wales/Caneuon Traddodiadol Cymru. Its out-take Now Westlin’ Winds, with Martin Carthy accompanying on guitar, from the same sessions appeared on the seasonal round anthology, All Through The Year (Fledg’ling, 1991).

Long associated with the Newcastle upon Tyne folk scene, whether ‘knitting’ bags for her pipe-maker husband’s much sought-after Northumbrian pipes or just singing or adding drolleries of the spoken monologue or parody song type, she appeared on 50 Years of Folk Music in Newcastle (Ceilidh Connections, 2009) performing her arch monologue Behave Yoursel’ – a treatise on declining standards in public places – and, accompanied by Tom Gilfellon on guitar, Generations of Change and Old Maid In A Garret. It was a no-frills double-CD celebrating a half-century of one of Britain’s finest folk hubs – the club that began as Folksong and Ballad before becoming the Bridge Folk Club and most especially known from its time at the Barras Bridge Hotel in the city. It ranked, I wrote in R2, as “one of the folk scene’s very most important outposts when the likes of Mike Waterson … willingly thumbed it from Hull to Liverpool (pre-motorway system) in order to visit the Spinners’ folk club.” I continued, “You get the club’s founding fathers – Johnny Handle and Louis Killen – in the glad company of past and present High Level Ranters (surely verging on the holotypic in a folk revival band sense and absolutely one of Britain’s finest), Chris Hendry, Ray Fisher, Pete Wood, John Brennan and others. … 50 Years of Folk Music in Newcastle brilliantly distils the essence of not merely one but this country’s whole folk club movement.”

Long associated with the Newcastle upon Tyne folk scene, whether ‘knitting’ bags for her pipe-maker husband’s much sought-after Northumbrian pipes or just singing or adding drolleries of the spoken monologue or parody song type, she appeared on 50 Years of Folk Music in Newcastle (Ceilidh Connections, 2009) performing her arch monologue Behave Yoursel’ – a treatise on declining standards in public places – and, accompanied by Tom Gilfellon on guitar, Generations of Change and Old Maid In A Garret. It was a no-frills double-CD celebrating a half-century of one of Britain’s finest folk hubs – the club that began as Folksong and Ballad before becoming the Bridge Folk Club and most especially known from its time at the Barras Bridge Hotel in the city. It ranked, I wrote in R2, as “one of the folk scene’s very most important outposts when the likes of Mike Waterson … willingly thumbed it from Hull to Liverpool (pre-motorway system) in order to visit the Spinners’ folk club.” I continued, “You get the club’s founding fathers – Johnny Handle and Louis Killen – in the glad company of past and present High Level Ranters (surely verging on the holotypic in a folk revival band sense and absolutely one of Britain’s finest), Chris Hendry, Ray Fisher, Pete Wood, John Brennan and others. … 50 Years of Folk Music in Newcastle brilliantly distils the essence of not merely one but this country’s whole folk club movement.”

Folk clubs were Ray’s driving force when it came to making music. She loved the folk club scene. She stoutly avoided recording under her own name. In an interview with me, published in Swing 51Crab Wars she and a front row of nasty people hid crab shells under their chairs. At the critical moment, the concealed crab carapace percussion was whipped out and clattered in an attempt to get the Kippers to corpse.

PS At Ray’s funeral in Whitley Bay there was much piping and singing. At one point Martyn Wyndham-Reed movingly sang The Rose, a Greenwich Village single of his on which Ray had sung in 1984 – the same song that Bette Midler had sung. Adding the backing vocals were Cilla Fisher, Di Henderson (on whose By Any Other Name (DH, 1991) Ray had also sung) and Cilla’s daughter Jane.

Jane sings with the Glasgow-based electro, punk and rock’n’roll band Fangs. Wonderful to discover that yet another generation of Fishers is singing. For more information and to try This Is Art for starters, visit http://www.myspace.com/fangsfangsfangs

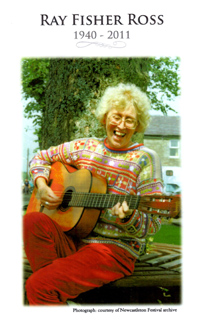

The main image is © Sandy Paton/Folk-Legacy Records, cropped from the album sleeve of Willie’s Lady, the yesty image of Ray from her funeral programme is courtesy of the Newcastleton Festival archive, photographer unknown. The copyright of all other images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers.

With thanks to Cilla Fisher.

19. 9. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The one has a lot to do with thinking about rhymes, rhythms, mythologies and conversations. The music from Panta Rhei, Ornette Coleman, Dick Gaughan, Pentangle, Traffic, Talking Heads, Márta Sebestyén, Martin Simpson (with Dick Gaughan), Steve Tilston and Aruna Sairam.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The one has a lot to do with thinking about rhymes, rhythms, mythologies and conversations. The music from Panta Rhei, Ornette Coleman, Dick Gaughan, Pentangle, Traffic, Talking Heads, Márta Sebestyén, Martin Simpson (with Dick Gaughan), Steve Tilston and Aruna Sairam.

Nachts – Panta Rhei

Nachts – Panta Rhei

This particular performance isn’t typical of the East German jazz-rock Panta Rhei, lazily rather than waggishly labelled the Chicago of the East. Back in the day they proved to be the birthing ground of many of the most important Ostrock bands with personnel streaming out all over the place. Members went on, for example. to Karat and Lift. Overwhelmingly though, the band’s image was shaped by its two lead vocalists Herbert Dreilich and Veronika Fischer.

Nachts is a Dreilich composition sung by Fischer. It begins with an opening electric guitar statement. Drums with telling cymbal work enter and the instruments fall into place. The arrangement features prominent piano and flute and keyboard washes. The mood created is romantic. Vroni Fischer is singing solo. “Perhaps you also think of me/of hours full of happiness/That I’ll finally come to you/Back to you.”

Nachts translates as ‘nights’ (in its adverbial sense) and is a wistful torch song of longing and imagining a lover’s return or reunion. The song is much anthologised whether on Amiga reissue compilations or the touchy-feely anthology Abendstimmung (‘Evening mood’). It first appeared as the B-side of Panta Rhei’s Hier Wie Nebenan (‘Here like next-door’) (Amiga 4 55 880) in 1972 but was elbowed off the band’s debut LP.

Amiga was the only deal in town and it was a small miracle for any East German rock group to get to record, let alone get an album released. Everything was scrutinised, nothing was left to chance or deemed coincidence when officials wielded their mighty, all-powerful red pens. This is not to say that Nachts is anything subversive but its lyrics could allow the ‘wrong’ sort of interpretation – “Slowly the night passes/A new day is beginning…” Said day is full of sunshine, it continues for the twitchy-pen censor. Long before technology brought in CCTV and surveillance cameras, the German Democratic Republic was a state that never slept for the night had a thousand eyes, paid and volunteer.

It eventually ended up on Panta Rhei’s Die frühen Jahre (‘The Early Years’) LP for Amiga in 1981. On Abendstimmung the argus-eyed will note that their name changed from Panta Rhei (Greek for ‘Everything flows’) to Pantha Rhei. It could have been a proofing error, a dumbing-down or a confusion with Panther. Let’s not speculate, though. It was a mistake, an honest one and nobody wants the inquisition to burst in. From Die frühen Jahre or Abendstimmung etc

Tom Paine’s Bones – Dick Gaughan

Wandering around Lewes in West Sussex, I made not so much a pilgrimage as a visit to the place where Tom Paine, a political polestar by day or night, lived. Looking up at the stout-timbered house on the high street, Graham Moore’s tribute, as sung by Dick Gaughan, kept running through my head.

It lodged in my head for months with its “I will dance to Tom Paine’s bones/Dance to Tom Paine’s bones/Dance in the oldest boots I own/To the rhythm of Tom Paine’s bones…” Then in July Barbara Dane and I had an email exchange, thanks to Leon Rosselson, that touched on Paine. We evoked him as a mutual inspiration. In August Aruna Sairam and I got chatting about the importance of visiting places with an artistic connection. By then, Dick Gaughan’s magnificent interpretation of the song was clearly not going away. From Outlaws & Dreamers (Greentrax CDTRAX 222, 2001)

More information at http://www.dickgaughan.co.uk/

Theme From A Symphony (Variation One) – Ornette Coleman

Theme From A Symphony (Variation One) – Ornette Coleman

Dancing In Your Head (A&M Horizon, 1977) was a turning-point in free-form jazz and the reason it made such a strong impression on me, I thought, was Midnight Sunrise, recorded in January 1973 in Jajouka, Morocco. It included the Master Musicians of Jajouka. Midnight Sunrise also connected with Coleman’s two Themes From A Symphony and their harmolodics. (“This means the rhythms, harmonies, and tempos are all equal in relationship and independent melodies at the same time.” When I first encountered it, the album’s three tracks seemed like some gooey, honey-based delectable confectionary with nuts stirred in. Listening back to it, this track proved to be the key. Familiarity can breed new insights. From Dancing In Your Head (Verve 543 519-2, 2000)

I’ve Got A Feeling – Pentangle

One of Pentangle’s finest songs, originally part of their double-LP Sweet Child (1968). From Sweet Child (Sanctuary CMDDD132, 2001)

The Low Spark of High-Heeled Boys – Traffic

The Low Spark of High-Heeled Boys – Traffic

The post-hit band Traffic incarnation was one of their finest. Their music distilled so much as they crammed all those ideas into their music. This particular song from Steve Winwood and Jim Capaldi from their 1971 album of the same name does wonderful things with tensions. Those tensions apply to both the music and the lyrics. From The Low Spark of High-Heeled Boys (Island 314 548 827-2, 2002)

Once In A Lifetime – Talking Heads

And then one thing leads to another. Same as it was. From Sand In The Vaseline (Sire Records 0777 7 80466 2 2, 1992)

Bú-küldöző – Márta Sebestyén

On this album, Márta Sebestyén sings (as well as playing tin-whistle and drum) as part of a trio, with Balázs Szokolay Dongó contributing bagpipes, shepherd’s flutes, fujara, tárogató (Hungary’s indigenous ‘clarinet), saxophone and vocals, and Mátyás Bolya playing koboz (fretless lute) and zithers. This particular suite, Bú-küldöző (‘Sending Off Sorrow’) banishes misfortune so gloriously. It begins with Mikor kend es Laci bátyám… (If You Too, Laci…) into Kecskés tánc (Goat-like Dance) into Ihogtatás (A Rhythmic Yell). A piece of musdic that came out of this August’s conversation with Aruna Sairam. From Nyitva látám mennyeknek kapuját/I Can See the Gates of Heaven (SM 001, 2008)

More information in Hungarian and English at http://sebestyenmarta.hu/

Brother, Can You Spare A Dime? – Martin Simpson

Brother, Can You Spare a Dime? is a song birthed in the Great Depression. Yip Harburg’s lyrics, set to music based on a remembered Russian lullaby by Jay Gorney in 1931 captured the mood of an age. Its title is so economical it is staggering. Rudy Vallée recorded it. Bing Crosby sang it (his was the version I first remember). Tom Waits cut it, though his cover did not do much for me. George Michael included it in his Symphonica tour repertoire, a tour that started at Prague’s State Opera House in late August 2011.

Martin Simpson does this song solo in concert. But albums do not need to be ‘concert captures’. This version showcases Dick Gaughan singing and he is on great blooming marvellous form. The whole construct is a gem to stick on repeat play. . From Purpose + Grace (Topic Records TSCD584, 2011)

More information at http://www.martinsimpson.com/

Ijna (Davy Ji) – Steve Tilston

This concluding track from Steve Tilston’s 2011 album is his tribute to Davy Graham. It’s a piece for solo guitar and it uses the groove and tonalities of Graham’s playing as its launch pad. It’s not a flashy composition. It could have been. It sets out to capture the essence of the man and his guitar playing. The ‘Davy Ji’ in brackets is an Indian suffix connoting respect and, of course, Davy was a great questing individual who loved the Pandora’s box that raga opened up. It coincided with proofing galleys for Davey’s entry in an upcoming supplement to the Oxford Dictionary of National BiographyFrom The Reckoning (Hubris Records HUB 006, 2011)

More information at http://www.stevetilson.com

Kalinga Nartana – Aruna Sairam

Kalinga Nartana – Aruna Sairam

There are several accounts of this story. Let’s stick to one of those ‘Once upon a times’. Once upon a time, Kalinga or Kāliyā, a nāga or serpent being, had driven into exile in the River Yumuna and taken up residence at Vrindavan – in the modern-day Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. Garuda, ferocious eagle-kin foe of snakes, had driven him into exile and he was not a happy nāga. He was very cross. However, Garuda could not touch him in Vrindavan because he had riled somebody so royally that he had a workable curse placed on him, ensuring Vrindavan was somewhere he could not go. So there Kalinga – we will stick to his name in this song – was safe in the knowledge that he could spread his foul poison. With 110 hooded heads – imagine a multi-headed king cobra with attitude and then some – Kalinga had venom to share. He decimated the area for leagues around. The local humans were terrified and steered clear of Kalinga’s lair.

One day some children were playing ball and the ball landed in the Yamuna. One boy went in after it and Kalinga rose from his lair at the commotion and wrapped the child in his coils. The child fought back and turned the tables, for it was Krishna. Venom was flying and the child Krishna grew so huge that Kalinga ran out of snake, so to speak, and had to let him go. Then Krishna danced with the weight of the world on Kalinga’s heads and bested him. His life was spared at his wives’ intervention by their worshipping Krishna. Krishna spared him and allowed him to leave, a chastened nâga.

One day some children were playing ball and the ball landed in the Yamuna. One boy went in after it and Kalinga rose from his lair at the commotion and wrapped the child in his coils. The child fought back and turned the tables, for it was Krishna. Venom was flying and the child Krishna grew so huge that Kalinga ran out of snake, so to speak, and had to let him go. Then Krishna danced with the weight of the world on Kalinga’s heads and bested him. His life was spared at his wives’ intervention by their worshipping Krishna. Krishna spared him and allowed him to leave, a chastened nâga.

This is the story with which Aruna Sairam concluded her concert at London’s Royal Albert Hall on 27 July 2011. This is a recording on the same thillana – a rhythmic form kin the north’s tarana form from 2002. Kalinga Nartana is by the 18th-Century C.E. composer, Ootukkadu Venkatasubba Iyer – the first part of his name is a typical Karnatic geographical reference, in this case to Oottukkadu, a village near Kumbhakonam in modern-day Tamil Nadu. Aruna Sairam invests it with the sublime. It is phenomenal. From December Season 2002 (Charsur Digital Work Station CDWL067D, 2002)

The image of Aruna Sairam from Darbar 2009 is © Santosh Sidhu/Swing 51 Archives. The copyright of all other images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers.

16. 9. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] To be truthful, there really have been very few disc jockeys who have changed society’s attitudes to music. Tom Donahue introduced a virus to North American radio programming. Donahue’s infected the San Francisco Bay Area. By circumventing conventional playlist conventions, he wove an unconventional tapestry that enabled listeners to think beyond the commercially regulated 45 rpm format, think about LP-length tracks as a format and thus to think for themselves. The pendulum had swung slow for too long and it needed adjusting because it was no longer in time with the times. John Peel did that too, only he took things further and took his catholic tastes and musical worldview to places far beyond an English recording studio.

[by Ken Hunt, London] To be truthful, there really have been very few disc jockeys who have changed society’s attitudes to music. Tom Donahue introduced a virus to North American radio programming. Donahue’s infected the San Francisco Bay Area. By circumventing conventional playlist conventions, he wove an unconventional tapestry that enabled listeners to think beyond the commercially regulated 45 rpm format, think about LP-length tracks as a format and thus to think for themselves. The pendulum had swung slow for too long and it needed adjusting because it was no longer in time with the times. John Peel did that too, only he took things further and took his catholic tastes and musical worldview to places far beyond an English recording studio.

Maybe it took those with an open-minded, Rabelaisian streak to break the mould. John Peel had that streak but what he also possessed was a complete lack of ambition for turntable work as a springboard to hosting quiz shows on daytime television. He was, simply put, the most important, if not the most influential, broadcaster in the UK. That said, through his broadcasts on the BBC World Service and variously named British Forces radio stations, he reached out to a global audience making one of the world’s most important opinion-formers ever in music. It wasn’t all epiphany. He wasn’t selling epiphanies. Sure he shaped opinions but basically he gave people the chance to make their own minds up.

He was renowned for playing what he liked and generally liking and championing what he played (though sometimes he just played music that piqued his curiosity because he knew he was undecided enough about it to give it the benefit of the doubt). Arguably, he was the most important music broadcaster of his time in the world. If that curdles anyone’s milk, name the pretender to that throne.

He was renowned for playing what he liked and generally liking and championing what he played (though sometimes he just played music that piqued his curiosity because he knew he was undecided enough about it to give it the benefit of the doubt). Arguably, he was the most important music broadcaster of his time in the world. If that curdles anyone’s milk, name the pretender to that throne.

Born John Robert Parker Ravenscroft on 30 August 1939 in the Wirral in Heswall, Cheshire, he admitted that two records changed his life. One was Heartbreak Hotel; the other Rock Island Line. Peel borrowed his nom de wireless from a popular folksong. He talked about adventures out in the States during Beatlemania (and how he became an instant Beatle specialist with accent and instant exploitative ‘Liverpudlian’). Back in Britain, his attentions in his Radio London pirate radio days focussed on Country Joe & The Fish, Jimi Hendrix, the Incredible String Band, Pink Floyd, Forest, Principal Edward’s Magic Theatre, Tyrannosaurus Rex, Liverpool Scene and their kind.

He went on to BBC Radio One ushering in a period and patronage of acts such as the Undertones, Frank Chickens, Henry Cow, Oasis, Blur and worse. Droll, open and witty to an extreme, he gave exposure to generations of culturally significant music, without fear or (much) favour. His producer, John Walters once archly observed, “If Peely ever reaches puberty, we’re all in trouble.” He never sprouted musical pubes, thank heavens. He did, however, speak frankly about the consequences of carefree promiscuity in the pre-AIDS years. He remains a hero.

He went on to BBC Radio One ushering in a period and patronage of acts such as the Undertones, Frank Chickens, Henry Cow, Oasis, Blur and worse. Droll, open and witty to an extreme, he gave exposure to generations of culturally significant music, without fear or (much) favour. His producer, John Walters once archly observed, “If Peely ever reaches puberty, we’re all in trouble.” He never sprouted musical pubes, thank heavens. He did, however, speak frankly about the consequences of carefree promiscuity in the pre-AIDS years. He remains a hero.

He died on a working holiday in Cuzco, Peru on 25 October 2004.

Check out the books John Peel: Margrave of the Marshes and Ken Garner’s The Peel Sessions: A Story of Teenage Dreams and One Man’s Love of New Music but most of all those Peel Sessions (such as June Tabor’s above).

29. 8. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] In July 1991, the first year that Tanz&FolkFest Rudolstadt was staged, just like the 2010 ‘edition’, it took place under blue skies in baking temperatures. The 1991 bill served up plenty of scope for serendipitous discoveries of the new kind and reacquainting oneself with familiar acts. Bernhard Hanneken’s festival programming for the 2010 festival did something similar in spades – only to surfeit degrees (let’s not talk of lampreys) – with 27 stages scattered over the town. Then add a pedestrian street dedicated to street music. The highlight of that section of the festival’s programming was 70-year-old Klaus der Geiger (‘Klaus the Fiddler’), a Cologne-based street musician and busking institution, a man who studied with the composer-musician Pauline Oliveros, turned his back on mainstream classical music, turned to street music and has stayed radical.

[by Ken Hunt, London] In July 1991, the first year that Tanz&FolkFest Rudolstadt was staged, just like the 2010 ‘edition’, it took place under blue skies in baking temperatures. The 1991 bill served up plenty of scope for serendipitous discoveries of the new kind and reacquainting oneself with familiar acts. Bernhard Hanneken’s festival programming for the 2010 festival did something similar in spades – only to surfeit degrees (let’s not talk of lampreys) – with 27 stages scattered over the town. Then add a pedestrian street dedicated to street music. The highlight of that section of the festival’s programming was 70-year-old Klaus der Geiger (‘Klaus the Fiddler’), a Cologne-based street musician and busking institution, a man who studied with the composer-musician Pauline Oliveros, turned his back on mainstream classical music, turned to street music and has stayed radical.

One of the lessons attending a fair few Tanz&FolkFest Rudolstadts has taught me is to welcome and embrace the unexpected. Even handling the English-language content for the festival programme cannot always be a preparation. One perfect illustration of embracing the unexpected happened the night before the festival. In Prague. On 1 July 2010.

Baráčnicka rychta is a restaurant that is modern-day Prague on a platter with a serving of bygone Prague added to the dish. (This is not a restaurant review but the tavern serves an exquisite Czech repertoire of dishes. In addition in 2010 it was a rare Prague outlet for the Svijany brewery’s beers.) Even with a street map it is hard to find. (And harder to leave.) One level down, overlooked by the dining area, it has a dance hall. Suddenly, mid meal, there was an eruption of electricity downstairs and the Czech rock band Natural kicked off its set. (Imagine being a once-Czechoslovakian and being wafted back to pre-disuniflication, imagine coming from Tottenham and listening to the Dave Clark Five rather than the sound of riots and buildings burning). For Czechs of a certain generation Natural meant something. They were opening for the Bulgarian rock group D2. Instead of being the ruination of the evening, it was a flash of serendipity to be warmly embraced and enjoyed. The following Saturday D2 would come back to haunt me in Rudolstadt…

Enough of the Czech Republic: let’s return to Germany. Notably, 2010 brought back three of the highlights of the 1991 festival with the Sardinian vocal temptress Elena Ledda, the Czech iconoclasts Jablkoň and Bavaria’s Wellküren. (Jablkoň in the Stadttheater (‘town theatre’) sounded ‘proper all grown-up’ compared to the exhilarating, caterwauling punk-folk scruffiness of their set beside the ramshackle, run-down Boulevard in July 1991.) As to the delights of the familiar, Arlo Guthrie on the Heidecksburg’s main castle stage was remarkable. He had the whole Thüringer Symphoniker Saalfeld-Rudolstadt visibly tensing and waiting for the conductor’s wand as Guthrie, in trademark fashion, prolonged his introductions. His internationalist introduction to his father, Woody Guthrie’s This Land Is Your Land was truly special. He explained how other nationalities have done find-and-replace-style searches with its geographical references. That’s about a fine a testimony to folksong’s internationalism as I know.

The Hindustani violinist Kala Ramnath, with Abhijit Banerjee on tabla, gave one of ten finest Hindustani recitals in the Stadttheater (town theatre’) it has ever been my privilege and pleasure to witness in three or so decades. (My detailed review appeared in the Autumn 2010 issue of the UK-based Indian arts magazine Pulse.) By comparison, her concert in the Stadtkirche (‘town church’) was excellent though marred by off-stage distractions. There were too many aural and visual distractions from creaking pews to a couple canoodling right at the front (bringing to mind past injunctions and laments fro Ravi Shankar). Thankfully, Kala Ramnath deep into her spontaneous composition missed the canoodling. Alas I didn’t.

The discoveries were many but three in particular stand out. One chance discovery was the jam-band E.G.s. With temperatures in the 30s, they played their delightful German-language rock and occasional reggae repertoire on the Theaterplatz stage to an audience largely sheltering from the sun under the proverbial linden trees. They were arresting. Their music throbbed with life. It was perfect festival music. The main three discoveries, however, began with the German songstress Tine Kindermann. She reconstructed her glorious 2008 schamlos schön (‘Shamelessly beautiful’) on the main stage in the marketplace (Am Markt). Her theremin-like musical saw playing was centre stage and it proved perfect for adding enough eeriness to counterbalance the sunshiny day. She puts the Grimm back into macabre. Ever pondered how sanitised bedtime Märchen (‘fairy stories’) are now? Two further discoveries completed Hunt’s prial of festival discoveries. Namely, the frankly astounding Bulgarian band Diva Reka (meaning ‘Wild River’) and Cedric Watson & Bijoux Creole, who closed the finale concert. Both appeared on the marketplace stage.

During a discussion entitled ‘Wine in New Wineskins?’ I mentioned Diva Reka. They were a recent project exploring possibilities for acoustic-ethno music while staying grounded in Bulgarian folk traditions. Apparently, usually they performed as an instrumental quartet. At the festival they had drafted in two members of Bulgaria’s Eva Quartet (who had been at the festival in 2000). They melded a variety of musical styles including some classical music, some rock but especially jazz. It was far removed from the Bisserov Sisters back in 1991. Who were, are and ever shall remain dear to my heart. (On the planet only Mitra Bisserova has ever persuaded me, a non-dancer with a bad knee (or two) and heart whispers, to dance to Bulgaria’s nasty knee-knottingest rhythms.) At the end of the talk – remember the beginning of the paragraph? – a Bulgarian National Radio journalist approached to garner some quotes about Diva Reka. We chatted about Diva Reka, the Bisserov Sisters back in July 1991 and then with a barely concealed smile I dropped in having seen D2 the other night in Prague. You could not make it up…

As always, sitting in England and reading the book-size festival programme, it’s astonishing how much I missed but also how much I saw. Quite frankly, there is no festival quite like Rudolstadt. Partisan hand on unpartisan heart.

More information at http://tff-rudolstadt.de/

The festival programme’s image above is by Jürgen B. Wolff and nobody is trying to steal his copyright from him because he is a very good egg.

22. 8. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] By any standard, she is one of the greats of popular music. He is, in my opinion and that of many others’, the finest sitarist of his generation, with a work ethic and melodicism drilled into him through studying sitar with his father, the legendary – for once the word is deserved – Vilayat Khan and working as a Bollywood session musician. This world premiere looked to their recently released collection of sitarist-singer Shujaat Khan’s settings to traditional melodic or lyrical themes, Naina Lagaike – to stick to the CD artwork’s spelling – though the concert programme carried the more accurate “Naina lagai ke”, meaning ‘I rue having locked eyes with you’ was an unmissable event. It was also the programme’s baptism of fire before a paying public.

[by Ken Hunt, London] By any standard, she is one of the greats of popular music. He is, in my opinion and that of many others’, the finest sitarist of his generation, with a work ethic and melodicism drilled into him through studying sitar with his father, the legendary – for once the word is deserved – Vilayat Khan and working as a Bollywood session musician. This world premiere looked to their recently released collection of sitarist-singer Shujaat Khan’s settings to traditional melodic or lyrical themes, Naina Lagaike – to stick to the CD artwork’s spelling – though the concert programme carried the more accurate “Naina lagai ke”, meaning ‘I rue having locked eyes with you’ was an unmissable event. It was also the programme’s baptism of fire before a paying public.

Concerts that wrong-foot and thwart expectations are amongst the best. This one did so to no little degree. That said, there were elements in the auditorium who for some benighted reason or the other thought it should be, or wanted to turn it into an Asha Bhosle Bollywood bash. They wanted Bollywood now and called out greatest hit titles. To state the flaming obvious, what should have been the giveaway clue was the dual billing on the tickets and concert programme.

Shujaat Khan clarified upfront that they were “doing something very different” before the instrumental sextet of sitar, flutes, guitar, keyboards/synthesiser and two percussionist attuned the audience’s ears to the evening’s sound, with a piece attributed to the semi-mythical Amir Khusro. Though the audience in due course got a taste of Bollywoodisms with, say, Mera Kuchh Saamaan (‘Some of my belongings’) and even one of her father, Dinanath Mangeshkar’s Marathi-language martyr songs, it was the album’s Aaja Re Piya Mora (‘Come back my love’) and their kind that elevated this concert.

Spontaneous creativity should come with blemishes. “Give me spots on my apples/But leave me the birds and the bees,” is, of course, part of a verse generally attributed to Amir Khusro. In it he distils how each act of musical creation should be different and individual, just as it is the apple’s flavour and content that is the gardener’s goal, not an fruit sized and shaped by the conformities of the marketplace. That is, naturally, merely one interpretation. Amir Khusro’s left many puzzles. The main puzzle of this particular night was the absence of a Shujaat Khan sitar solo.

With Saregama having recorded the run of UK concerts, the Royal Festival Hall concert may well have captured a piece of history being made. Let’s hope.

CD image courtesy of Saregama, © Saregama 2011

15. 8. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Great Folk Jukebox was billed as “A Tribute to Singing Englishmen with Marc Almond, Bishi, Green Gartside, Bella Hardy, Robyn Hitchcock, Lisa Knapp, Oysterband & June Tabor” (with, as the Oysters’ John Jones quipped, “the beast that is Bellowhead” – nine thereof – as house band). The ‘Singing Englishmen’ part was a doffing of the cap to a Festival of Britain concert held on 1 June 1951. Although there were allusions to Bert Lloyd’s The Singing Englishmen – a slim songbook published to coincide with the St. Pancras Town Hall concert and its six themes of freedom; courting; “On the job”; seas, ships and sailormen; “Johnny has gone for a soldier”; and “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of happiness” – in truth, this was more like a gathering of the tribes.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Great Folk Jukebox was billed as “A Tribute to Singing Englishmen with Marc Almond, Bishi, Green Gartside, Bella Hardy, Robyn Hitchcock, Lisa Knapp, Oysterband & June Tabor” (with, as the Oysters’ John Jones quipped, “the beast that is Bellowhead” – nine thereof – as house band). The ‘Singing Englishmen’ part was a doffing of the cap to a Festival of Britain concert held on 1 June 1951. Although there were allusions to Bert Lloyd’s The Singing Englishmen – a slim songbook published to coincide with the St. Pancras Town Hall concert and its six themes of freedom; courting; “On the job”; seas, ships and sailormen; “Johnny has gone for a soldier”; and “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of happiness” – in truth, this was more like a gathering of the tribes.

The link to the 1951 songbook was tenuous and stylistically a few miles short of a million from the Workers’ Music Association’s original event. Crediting Pete Bellamy (Gartside), Martin Carthy (Hitchcock), Shirley Collins (Bishi) and Anne Briggs (Hardy) as influences pointed to the place of folk revival singers in today’s appreciation of folksong. Almond prowled and commanded the stage with Reynardine – all florid gestures and torch song mannerisms – to fashion a bravura performance. Bishi’s Flash Company for “all the pretty flash girls” with mandolin (played by Bellowhead’s Benji Kirkpatrick) and cello (Bellowhead’s Rachael McShane) supporting her minimalist sitar felt more lived-in and flowed more freely than her Salisbury Plain. Hitchcock ‘in’ matching shirt and guitar ripped the guts out of Sam’s Gone Away. In those three cases, it became the singer not the song – and far from that implying in a bad way.

Divers And Lazarus – it had actually figured in the 1951 choral performance – from the Oysterband and Tabor put the song first. Talking in the intermission to a Marc Almond devotee, the performance that had touched him the most was June Tabor’s unaccompanied delivery of The Blacksmith. That made two of us.

Small print

With thanks to Dave Arthur

8. 8. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] June Tabor & Oysterband, Lady Maisery, Mike Waterson, Nørn, Bahauddin Dagar, Peter Bellamy, Bob Weir and Rob Wasserman, the Home Service, Aurelia and the Velvet Underground. And lots to do with work, the spirits of Rudyard Kipling, Robert Mitchum, Bob Hoskins and the summer 2011 music festival season.

[by Ken Hunt, London] June Tabor & Oysterband, Lady Maisery, Mike Waterson, Nørn, Bahauddin Dagar, Peter Bellamy, Bob Weir and Rob Wasserman, the Home Service, Aurelia and the Velvet Underground. And lots to do with work, the spirits of Rudyard Kipling, Robert Mitchum, Bob Hoskins and the summer 2011 music festival season.

Love Will Tear Us Apart – June Tabor & Oysterband

The Oysterband – Ray ‘Chopper’ Cooper (cello, mandolin, bass guitar, harmonium, vocals), Dil Davies (drums, cajón), John Jones (lead vocals, melodeon), Alan Prosser (guitars, kantele, fiddle, vocals), and Ian Telfer (fiddle) – reunites here with June Tabor to splendid effect..

June Tabor and John Jones invest this song of Joy Division’s with an enormous dignity and pathos. “Why is the bedroom so cold?/You turn away on your side…” is a pretty haunting image of a love going wrong. The cello-led arrangement captures a chill wind blowing no-one any good. No need to explain any more. It is a masterpiece of an interpretation of a great song beautifully captured from one of the most glorious albums of 2011 thus far. From Ragged Kingdom (Topic TSCD585, 2011)

More information, tour dates and all that jazz at http://www.oysterband.co.uk/

Sleep On Beloved – Lady Maisery

Sleep On Beloved – Lady Maisery

Lady Maisery is the trio of Hazel Askew (of the Askew Sisters), Hannah James and Rowan Rheingans. Folk trio, I guess you’d say. Their debut reveals a remarkable palette of of assimilated influences and inspirations. They include Pete Bellamy’s setting of Rud the Kip’s My Boy Jack, the witchy Willie’s Lady (Martin Carthys and Ray Fishers passim), a pairing of labajalg (“an Estonian flat-footed waltz,” and don’t shoot the messenger) and a polska (“written especially for singing by the Swedish vocal group, Kraja”), a music hall piece (from George Fladley of Derbyshire via Muckram Wakes of Derbyshire) and this lowering-down hymn from the Sankey songbook. This particular piece chimed because of thinking about Mike Waterson. It is a wonderful album. From Weave & Spin (RootBeat Records RBRCD09, 2011)

http://www.ladymaisery.com and http://www.rootbeatrecords.co.uk/

Tamlyn – Mike Waterson

Remember Mike however you wish. If you fancy a bit of parody right now, even if it’s under 60 seconds in length, his solo album had Bye Bye Skipper. Right now, a deeper draught is called for. Miss the photograph of Mike pushing the wheelbarrow on the original LP. Scandalously The Times failed to run an obituary of Mike Waterson so in revenge we barbecued the pigeon that brought the news to the desert island. Another Murdoch organ mishap. From Mike Waterson (Topic Records TSCD516, 1999)

Derek Schofield and Ken Hunt’s obituaries of Mike Waterson are, respectively, at http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2011/jun/22/mike-waterson-obituary

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/mike-waterson-singer-and-songwriter-with-the-watersons-luminaries-of-the-english-folk-scene-2301867.html

Ossemanidesh – Nørn

Ossemanidesh – Nørn

Last month’s GDDs included this fantastical Swiss vocal trio’s Lahillè – a track from their debut album, Fridj – and a suggestion that updates would follow. Here is the first bulletin. Ossemanidesh is from their third album Urhu, their musical programme about time.

They sing in an imaginary language they call Nørnik, so there’s no sense to be had from what they sing but masses of feeling to draw upon. It is the equivalent of abstract painting. Imagine Alexandre Calame and Caspar Wolf crossed with Joan Miró. Compounding these confusions, live they bring to bear a remarkable sense of musical theatre, certainly evinced by their performance at TFF Rudolstadt in July 2011, combined with phenomenal musicianship. This track from the same programme as the album it comes from, was recorded in the winter of 2010. Exceptional stuff that allows the listener to make all manner of judgements about the music uninfluenced by semantics. From Urhu (no name, no number, no date)

More information at www.norn.ch

Puriya Kalyan- Bahauddin Dagar

The death of Indian film-maker Mani Kaul (25 December 1944-6 July 2011) provoked a stream of associations, mainly of the dhrupad kind. The rudra vina player Bahuddin Dagar features in his music documentary film Dhrupad (1982) and his rumpy-pumpy-and-parrot drama The Cloud Door (1995). Additionally, the death of the rudra vina player Asad Ali Khan (1937-14 June 2011) was on my mind. This is an especially fetching and memorable exploration of the well-known evening raga. Recorded in March 2000 in Bombay, it reaches the parts, so to speak… From Rudra Bin (India Archive Music IAM CD 1077, 2005)

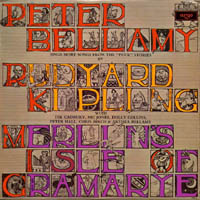

Puck’s Song – Peter Bellamy

Puck’s Song – Peter Bellamy

I think about Peter Bellamy a great deal and for many reasons. For his music, of course. That goes without saying. But also for his enthusiasm, enthusiasms and enthusiastic phone calls coming out of the blue. For championing Rudyard Kipling (this was his second album of Kipling settings) when many casually put Kipling obsession down as antediluvian or imperialistic and irrelevant.

And most of all, after the music and the man, and probably not karmically healthy, I kick his arse for taking his own life.

Most recently on account of so many people discovering and locating Bellamy’s music. A new generation of listeners and a new wave of interest. If it is possible to look down and say, “I told you so!” then Pete is saying it now.

Wrote Peter Bellamy for this album’s original release in 1972, “The Run of the Downs is a lyric tour of Sussex, in the manner of such traditional pieces as A Tour of the Dales. The tune is taken from the English country dance Morris On which also lent itself to Cornish Floral Dance.” The Downs in question are the South Downs of Sussex. Nic Jones provides the fiddle accompaniment. From Merlin’s Isle of Gramarye (Talking Elephant TECD178, 2011)

Click on for the label website, http://www.talkingelephant.co.uk/

The Winners – Bob Weir and Rob Wasserman

“Sing the heretical song I have made…” quotes Bob Weir in his setting of the Rudyard Kipling poem. Thinking about Rud the Kip prompted memories of this performance, recorded in the autumn of 1988. One time after doing an interview, we chinwagged and talk turned to Rudyard Kipling and Peter Bellamy. It emerged that Weir had his Kipling moments, too. But that should be a story for another time. The line “He travels the fastest who travels alone!” is one of my favourite travel tips. From Live (Grateful Dead Records GDCD 4053, 1997)

The Kipling Society is at http://www.kipling.org.uk/

Alright Jack – Home Service

Alright Jack is a song that became and stands as a cornerstone of the Home Service’s repertoire. There are many things I could say about this song and this performance and the song’s transferability. Suffice it to say that I shall delegate the job to Bob Hoskins, given what he said in The Gurudian (sorry, another poor joke). Asked “Which living person do you most despise, and why?” Hoskins answered splendidly. He said, “Tony Blair – he’s done even more damage than Thatcher.” And that is the reason why John Tams’ song lives on and is still so cogent, pertinent and resonant. Bliar was enough to have brought out and bring out the intemperate and agricultural language in anyone. Bob Hoskins’ reply was a model of restraint. PS And Bliar’s patronising piece on Durham in British Airways’ flight mag for July 2011 is a model of hypocritical cant. From Live 1986 (Fledg’ling FLED3085, 2011)

Bob Hoskins’ full interview appeared in The Guardian of Saturday, 18 June 2011. Read Rosanna Greenstreet’s excellent Q&A at http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2011/jun/18/bob-hoskins-interview-neverland

Vous et Nous – Aurelia

Vous et Nous – Aurelia

Aurelia is Aurélie Dorzée (violin and voice in particular), Stephan Pougin (percussion and kit drums) and Tom Theuns (guitar and voice in particular). Aurelia are still pretty much unknown beyond Belgium. I never got – and never is a big word – the casual dismissing of Belgium as a cultural birthing ground and environment. Belgium’s roots music scene is spectacular. Maybe it is the linguistic factors – three national languages, Flemish, French and German – with each language group accorded their own parliament under the Belgian constitution. Maybe that puts off monoglot nations or one-language minds and prompts petty cultural sniping. Love the way that Theuns, a mainstay of the Flemish band Ambrozijn, switched from Flemish to French for love.

The Hour of the Wolf, the title comes from Ingmar Bergman, is another side of bringing it all back home. It is remarkable, one of the finest albums to come out of Belgium in the last five to ten years. Live, they transform themselves into something else: a band playing music for dancers, quite unlike this album’s music. Aurelia is a major addition to Belgium’s roots music scene. From The Hour of the Wolf (Home Records, 2011)

http://wwww.homerecords.be/francais/aurelia/wolf.php

http://www.aurelia-feria.com/

Rock & Roll – Velvet Underground

Rock & Roll – Velvet Underground

Around the turn of the year – 1971 into 1972 – thanks to the cartoonist Paddy Morris (IT, Cozmic Comics and later Northern Lightz), I fell in with Dez Allenby, Martin and Adrian Welham, collectively the psychedelic folk group Forest. (They had a couple of albums called Forest and Full Circle to their name on Harvest.) The associations and links piled up. Arguably, the one that bound us together the most was Loaded. We played it constantly. Its references were wide both musically and lyrically. ‘I Found A Reason’ had a tongue-in-cheek streak. ‘New Age’ had that wonderful opening gambit of faded glamour and fandom as well as name-checking Robert Mitchum. (He had given a monstrously humorous interview to Rolling Stone in 1971, anecdotes from which we still chuckled over. One anecdote gave a new insight to the expression ‘dog’s bollocks’.) I digress.

And there was Rock & Roll with that bass line. “Jenny said when she was just five years old/There was nothin’ happenin’ at all/Every time she puts on the radio/There was nothin’ goin’ down at all/Not at all…” is how it starts.

The lyric continues, “Then one fine mornin’ she puts on a New York station/She don’t believe what she heard at all/She started shakin’ to that fine, fine music/You know, her life was saved by Rock’n’Roll.”

Sometimes we all need to blow away the cobwebs. If one fine mornin’ you realise nothing’s happening, blast away the cobwebs with Rock & Roll. Elemental stuff. From the ‘Fully Loaded Edition’ of Loaded (Rhino 8122-72563-2, 1997)

The image of Nørn and Aurelia from TFF Rudolstadt 2011 are © Santosh Sidhu/Swing 51 Archives. The copyright of all other images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers.

1. 8. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Nigel Kennedy’s late May 2010 flourish, his Polish Weekend at the Southbank Centre, brought together an array of Polish jazz and musical talent that included Kennedy’s Orchestra of Life (playing Bach and Ellington), Robert Majewski, Anna Maria Jopek and Jarek Śmietana. Tucked away in the early Sunday afternoon slot was the Piotr Wyleżoł Quintet. A relatively recent development, aside from the band’s pianist-leader, it comprised Krzysztof Dziedzic on kit drums and Adam Kowalewski on double-bass, their fellow countryman Adam Pieroeńczyk on soprano and tenor saxes and the Czech Republic’s David Dorůžka on electric guitar.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Nigel Kennedy’s late May 2010 flourish, his Polish Weekend at the Southbank Centre, brought together an array of Polish jazz and musical talent that included Kennedy’s Orchestra of Life (playing Bach and Ellington), Robert Majewski, Anna Maria Jopek and Jarek Śmietana. Tucked away in the early Sunday afternoon slot was the Piotr Wyleżoł Quintet. A relatively recent development, aside from the band’s pianist-leader, it comprised Krzysztof Dziedzic on kit drums and Adam Kowalewski on double-bass, their fellow countryman Adam Pieroeńczyk on soprano and tenor saxes and the Czech Republic’s David Dorůžka on electric guitar.

The concert began over half-an-hour late because Kennedy, who wanted to emcee their appearance, arrived late. His brief, laddish introduction managed to shoehorn in two lessons in bad manners. His affable excuses in Polish and English sounded more ‘adorable me’ than apologetic. Next, he failed to mention Dorůžka and Pierończyk while individually introducing his Nigel Kennedy Quintet band-mates.

The Piotr Wyleżoł Quintet already had a CD release, Quintet Live – a concert affair recorded at Polish Public Radio’s Katowice studio – under its belt. Yet at times elements within the band seemed under-prepared or as if their minds were elsewhere or wandering. During Dorůžka’s opening composition Was This The Last Time?, Pieronczyk finished adjusting his soprano’s mouthpiece nano-seconds before his break; when Dorůžka tapped him on the shoulder, it hadn’t looked like cliff-edge timing, more like away with the fairies. Over Nicholas Patou, Dr. Holmes, Snake and Els Gats, the quintet’s strengths and weaknesses emerged.

The Piotr Wyleżoł Quintet already had a CD release, Quintet Live – a concert affair recorded at Polish Public Radio’s Katowice studio – under its belt. Yet at times elements within the band seemed under-prepared or as if their minds were elsewhere or wandering. During Dorůžka’s opening composition Was This The Last Time?, Pieronczyk finished adjusting his soprano’s mouthpiece nano-seconds before his break; when Dorůžka tapped him on the shoulder, it hadn’t looked like cliff-edge timing, more like away with the fairies. Over Nicholas Patou, Dr. Holmes, Snake and Els Gats, the quintet’s strengths and weaknesses emerged.

In the Purcell Room, Dziedzic’s kit cried out for another cymbal so he could quietly ride the rhythm. And while democratic divvying-up of solos is laudatory, few added much to the journey, to the narrative’s unfolding. Wyleżoł and Dorůžka’s were the prime exceptions. Next time, more eye contract, greater interplay, more preparation and closer ensemble playing.

Small print

The images of Piotr Wyleżoł and David Dorůžka are © Santosh Sidhu/Swing 51 Archives.

David Dorůžka’s website is at: http://www.daviddoruzka.com/ Piotr Wyleżoł’s appears to be under construction at http://www.piotrwylezol.com/

Note

This review was originally commissioned for Jazzwise but fell victim to the magazine’s austerity measures. Dorůžka is the grandson of the eminent jazz critic Lubo Dorůžka and favourite son of Petr Dorůžka of this parish.

25. 7. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Patrick Galvin’s death on 10 May 2011 in his birth city of Cork received some attention, the way that Ireland’s foremost poets and men-of-letters get written up. Born on 15 August 1927, his obituaries raised the response of ‘Oh no, that will not do.’ Galvin was more than a poet and dramatist in the way he chronicled and portrayed his homeland, its history and its people. He had a parallel life as a singer and writer of Irish songs. His recording career began at Topic – Britain’s and the world’s oldest independent record label – in the early 1950s. He contributed a number of 78 rpm singles with Al Jeffrey, an early largely unsung hero of the post-war Folk Revival, accompanying him. Amongst them, were songs now largely seen as, or deemed standard repertoire through, say, the Dubliners, Thin Lizzy and Sinéad O’Connor.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Patrick Galvin’s death on 10 May 2011 in his birth city of Cork received some attention, the way that Ireland’s foremost poets and men-of-letters get written up. Born on 15 August 1927, his obituaries raised the response of ‘Oh no, that will not do.’ Galvin was more than a poet and dramatist in the way he chronicled and portrayed his homeland, its history and its people. He had a parallel life as a singer and writer of Irish songs. His recording career began at Topic – Britain’s and the world’s oldest independent record label – in the early 1950s. He contributed a number of 78 rpm singles with Al Jeffrey, an early largely unsung hero of the post-war Folk Revival, accompanying him. Amongst them, were songs now largely seen as, or deemed standard repertoire through, say, the Dubliners, Thin Lizzy and Sinéad O’Connor.

On disc he broke ‘new’ ground at times when anti-Irish bigotry stymied the commercial release of such material. Galvin’s first Topic single was Bonny Boy backed with She Moved Through the Fair, followed by Brown Girl and My Love Came to Dublin, Wild Colonial Boy and Football Crazy, Wackfoldediddle and Johnson’s Motor Car and The Women are Worse Than the Men and Whiskey In The Jar.

This was powerful voodoo galvanising poet Padraic Colum’s supernaturalism, football madness from another, perhaps less sectarian age and full-tilt, proselytising Irish rebel songs. This was leavened, however, by his abiding beliefs in socialism and the brotherhood of man. Topic also released long-players with Irish Songs of Resistance – exactly what was rattled in the tins – in their titles. His records were released in the USA on Stinson and Riverside.

He worked, reworked or tweaked song fare. That might be for The Boys of Kilmichael on Jimmy Crowley’s Uncorked (1998) or, probably his most widespread song, James Connolly, recorded on The Black Family (1986) and by Christy Moore who first recorded it on Prosperous (1972). John Spillane set Galvin’s The Mad Woman of Cork to music for his Hey Dreamer. In this pool, an image rises. Moore said he had learned James Connolly “many years ago from Dominic Behan” making it part of a cycle, just as Patrick Galvin would have wished. Galvin thus represents a link between the Irish folksong tradition, Seán Ó Riada, Dominic Behan and another century’s flowering of Irish song. And poeticism of a wider sort too, of course. In his One Voice – My Life In Song (2000), Moore wrote in the specific context of James Connolly, “While these songs are in performance they belong in the air. No one cares who wrote them while I sing them, they belong to us collectively.”

Further biographical reading: Patrick Galvin’s memoirs Raggy Boy (New Island Books, 2002)

Further information: http://www.informatik.uni-hamburg.de/~zierke/folk/records/patrickgalvin.html and Ralph Riegel’s obituary from Eire’s Sunday Independent of 15 May 2011 http://www.independent.ie/obituaries/patrick-galvin-2647558.html

17. 7. 2011 |

read more...

« Later articles

Older articles »

[by Ken Hunt, London] Now, it’s only personal opinion. Still, hear out my theory. Every movement has its share of before-and-after benchmarks or epiphanies. They divide people who experienced them first-hand from those who got the experience passed down. On 1 June 1980, a date that shall forever remain hallowed in the annals of what we laughingly call England’s Folk Revival, Topic Records released a twelve-inch, nine-track masterwork known as 12TS411 in the trade and as Penguin Eggs to the punters that snaffled it up. It is no exaggeration to say that it took the folk scene by storm, much as Dick Gaughan’s Handful of Earth did the following year. The auteur of this cinematic masterpiece – certainly the songs he sang ran movies in my skull – was a 33-year-old guitarist and folksong interpreter called Nic Jones.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Now, it’s only personal opinion. Still, hear out my theory. Every movement has its share of before-and-after benchmarks or epiphanies. They divide people who experienced them first-hand from those who got the experience passed down. On 1 June 1980, a date that shall forever remain hallowed in the annals of what we laughingly call England’s Folk Revival, Topic Records released a twelve-inch, nine-track masterwork known as 12TS411 in the trade and as Penguin Eggs to the punters that snaffled it up. It is no exaggeration to say that it took the folk scene by storm, much as Dick Gaughan’s Handful of Earth did the following year. The auteur of this cinematic masterpiece – certainly the songs he sang ran movies in my skull – was a 33-year-old guitarist and folksong interpreter called Nic Jones. [by Ken Hunt, London] The Scottish folksinger Ray Fisher once told me that she had a series of scheduled performances in Czechoslovakia that were abruptly cancelled when the Soviet bloc forces had the bad manners to invade in 1968. The following year, rescheduled concerts finally took place. She recalled the mayor of one town greeting her. Two Soviet officers flanked him. The mood was tense. Then, one of them broke the ice by asking her excitedly whether she knew the Beatles. (With her winsome charm, no doubt she pulled it off effortlessly but alas I have no memory of how exactly she got out of that one.) As part of the cultural exchange, the tour introduced her to dudy – Czech bagpipes and ‘bagpipes’ in Czech – and she remembered the experience with wry fondness.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Scottish folksinger Ray Fisher once told me that she had a series of scheduled performances in Czechoslovakia that were abruptly cancelled when the Soviet bloc forces had the bad manners to invade in 1968. The following year, rescheduled concerts finally took place. She recalled the mayor of one town greeting her. Two Soviet officers flanked him. The mood was tense. Then, one of them broke the ice by asking her excitedly whether she knew the Beatles. (With her winsome charm, no doubt she pulled it off effortlessly but alas I have no memory of how exactly she got out of that one.) As part of the cultural exchange, the tour introduced her to dudy – Czech bagpipes and ‘bagpipes’ in Czech – and she remembered the experience with wry fondness. Born in Glasgow, Scotland on 26 November 1940, in 1962, she had married Colin Ross, the fiddler and piper, and later co-founder of the High Level Ranters, and settled in Tyneside. With her marriage to Colin, she was wed – or, as she sometimes joked – widowed to the pipes. She was one of six daughters – Jean, Joyce, Cindy, Audrey and Priscilla – and one token son – Archie – born into a family with catholic musical tastes that included light operatic and parlour fare (their father John Galbraith Fisher sang in the City of Glasgow police choir), Scots and, since their mother, Marion née MacDonald (known as Morag or Ma Fisher) had it as her mother tongue, Gaelic songs. Like many folkies of her generation, Britain’s skiffle movement was the springboard to a greater awareness of folk music. Through a fluke of fate and proximity, a bloke who owned a local record shop lent US import LPs on Folkways by Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, Buell Kazee and Aunt Samantha Bumgarner to Hamish Imlach, whose Cod Liver Oil and The Orange Juice – Reminiscences of a Fat Folk Singer – discusses the early Glasgow folk scene. Imlach borrowed them because he was the one with a record player that could play them.

Born in Glasgow, Scotland on 26 November 1940, in 1962, she had married Colin Ross, the fiddler and piper, and later co-founder of the High Level Ranters, and settled in Tyneside. With her marriage to Colin, she was wed – or, as she sometimes joked – widowed to the pipes. She was one of six daughters – Jean, Joyce, Cindy, Audrey and Priscilla – and one token son – Archie – born into a family with catholic musical tastes that included light operatic and parlour fare (their father John Galbraith Fisher sang in the City of Glasgow police choir), Scots and, since their mother, Marion née MacDonald (known as Morag or Ma Fisher) had it as her mother tongue, Gaelic songs. Like many folkies of her generation, Britain’s skiffle movement was the springboard to a greater awareness of folk music. Through a fluke of fate and proximity, a bloke who owned a local record shop lent US import LPs on Folkways by Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, Buell Kazee and Aunt Samantha Bumgarner to Hamish Imlach, whose Cod Liver Oil and The Orange Juice – Reminiscences of a Fat Folk Singer – discusses the early Glasgow folk scene. Imlach borrowed them because he was the one with a record player that could play them. Most important of all, many would consider, was Topic’s LP The Fisher Family, recorded in 1965 and released the following year. Its subtitle said ‘Traditional and New Songs from Scotland’. Bill Leader recorded it at the Fisher Family palace, while Joe Boyd, his assistant on the job (later to achieve other things through Witchseason, Island, Elektra, Reprise and more, but also the snapper that captured the cover image), slept in the car outside because there was no more room in the palace. At her funeral, her surviving sisters sang Ewan MacColl’s Come All Ye Fisher Lasses, the album’s opening track on which Ray had sung lead.

Most important of all, many would consider, was Topic’s LP The Fisher Family, recorded in 1965 and released the following year. Its subtitle said ‘Traditional and New Songs from Scotland’. Bill Leader recorded it at the Fisher Family palace, while Joe Boyd, his assistant on the job (later to achieve other things through Witchseason, Island, Elektra, Reprise and more, but also the snapper that captured the cover image), slept in the car outside because there was no more room in the palace. At her funeral, her surviving sisters sang Ewan MacColl’s Come All Ye Fisher Lasses, the album’s opening track on which Ray had sung lead. In 1991 she released her third and final solo album Traditional Songs of Scotland which complemented Saydisc’s English and Welsh companion volumes – Jo Freya’s Traditional Songs of England and Siwsann George’s Traditional Songs of Wales/Caneuon Traddodiadol Cymru. Its out-take Now Westlin’ Winds, with Martin Carthy accompanying on guitar, from the same sessions appeared on the seasonal round anthology, All Through The Year (Fledg’ling, 1991).