Articles

[by Ken Hunt, London] Darndest thing happened after drinking some fermented coconut juice. Passed out, woke up and I had been transported back to England and the only music I could hear was stuff with Martin Carthy on it. Still stranger it happened to coincide with his 70th birthday on 21 May 2011. Such a delightful coincidence. Truth is stranger than fiction. No, sorry, Ruth is stranger than Richard. Always get that wrong after a sea of reviving coconut cocktails.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Darndest thing happened after drinking some fermented coconut juice. Passed out, woke up and I had been transported back to England and the only music I could hear was stuff with Martin Carthy on it. Still stranger it happened to coincide with his 70th birthday on 21 May 2011. Such a delightful coincidence. Truth is stranger than fiction. No, sorry, Ruth is stranger than Richard. Always get that wrong after a sea of reviving coconut cocktails.

The Rainbow – Martin Carthy

The Rainbow – Martin Carthy

The Rainbow first appeared on disc on Martin Carthy and Dave Swarbrick’s 1969 masterpiece Prince Heathen. This is a solo version from 1978 that emerged out of the woodwork in 2010. Travelling over the North Yorkshire Moors on the way to interviewing Martin Carthy – or, in seadog terms, bearding him in his den – in Robin Hood’s Bay The January Man – Live in Belfast 1978 was a travelling companion.

The Rainbow, a tale of two maritime nations – Spain and England – at war, opens the Sunflower Folk Club set. But that isn’t why it leapt out. It leapt out because of its visual impact. This is harrowing stuff about no quarter given and, to introduce an anachronism, it is television for a pre-television age. From The January Man – Live in Belfast 1978 (Hux Records HUX119, 2010)

The Harry Lime Theme – Martin Carthy

Imagine the scenario. Anton Karas (1906-1985), who has shlepped his zither around to entertain his Wehrmacht comrades and officers, gets a gig in post-war Vienna. He comes to the attention of the British film director Carol Reed. He is making the film The Third Man. Reed hears the instrument’s far-fetched sound, probably has no flipping idea what a zither is, and hires Karas. The Harry Lime Theme becomes the film’s signature tune. Try unimagining that. It is so integral to the film’s atmosphere. Many years later, Carthy remembers and sets zither to guitar. Flaming brilliant. From Waiting For Angels (Topic TSCD527, 2004)

Bonny Kate – Martin Carthy and Dave Swarbrick

Bonny Kate – Martin Carthy and Dave Swarbrick

The title of this tune was in my head when we named our daughter. It was more influenced by Shirley Collins’ recording, though. This EP had long been out of catalogue by then. It was later missed off the Selections anthology even though most of No Songs appeared there. From No Songs (Fontana TE 17490, 1967)

Company Policy – Martin Carthy

One of Martin’s originals. When did war and warfare ever go out of fashion? This one concerns an extreme post of British outreach. “As an avid stamp collector when I was a little boy,” wrote Carthy in the notes, “I was, for some reason, fascinated by the Falkland Islands, and I remember first hearing the name Malvinas during the fifties and then approximately every ten years after that.” Yet another conflict that had nothing to do with oil. Oh, hang on, there was oil there as well. From Right of Passage (Topic TSCD 452, 1988)

The Maid And The Palmer – Brass Monkey

The Maid And The Palmer – Brass Monkey

Can’t imagine life on this infernal island without this everyday story of incest and damnation, originally released in 1983. I think of this track and I conjure memories of my friend, Howard Evans who played trumpet and flugelhorn in Brass Monkey. And I picture a young girl dancing to this track. Her dad said of Brass Monkey, “It was the most exciting thing I’d heard in ten years.” Her name was Roseanne Lindley. Mostly I think of Howard. And him talking about Martin staying at their house in Carshalton and waking in the early hours to the sounds of “flaming Carthy” still playing his guitar downstairs long after everybody else had turned in, working on bedding in a piece instead of going to bed. From The Complete Brass Monkey (Topic TSCD467, 1993)

Rave On – Steeleye Span

Originally released as a single, this unaccompanied cover of the Buddy Holly song garnered some notoriety. At one point the needle sticks. The record player duly gets a knock and continues. Other territories, the Netherlands, for example, were not in on the vocal joke and therefore excised the offending ‘a-wella-a-wella’ ‘stuck’ section. After all, no sane person was going to release a faulty record deliberately. From the Carthy Contemporaries volume of The Carthy Chronicles (Free Reed FRQCD-60, 2001)

Byker Hill – Martin Carthy

A song that only got better. From Life and Limb (Special Delivery SPDCD1030, 1990)

Famous Flower of Serving Men – Martin Carthy

Famous Flower of Serving Men – Martin Carthy

This studio recording fixes Carthy’s grafting of a tale on a tune half-inched from Hedy West. Its meaning and shifting meanings reinforce the latent potencies and potentialities of traditional song. He revisited the song on Waiting For Angels. From Shearwater (Castle Music CMQCD1096, 2005)

Stitch In Time – Martin Carthy

Martin Carthy popularised this song by his brother-in-law Mike Waterson. This is a live version recorded in December 1987 by Edward Haber, Natalie Budelis and Ilana Pelzig Cellum. It’s a morality tale about domestic violence. From the Carthy Contemporaries volume of The Carthy Chronicles (Free Reed FRQCD-60, 2001)

Prince Heathen – Martin Carthy and Dave Swarbrick

Prince Heathen – Martin Carthy and Dave Swarbrick

It is frankly impossible to imagine the impact, to put oneself back in those bygone shoes, of hearing Prince Heathen back in 1969. It felt like this song’s subject matter was just too outré to be sung aloud even though it derived from a published Child ballad. It concerns a battle of minds and wills. It involves non-consensual sex, marital rape and extraordinary cruelty. Carthy boldly and logically ditched the text’s happy ending in order to retain the force of this psycho-drama.

I first heard it in Collet’s at 70 New Oxford Street in London a week or two after its release. Hans Fried played the album to me and I had to have it. I bought my brand-new Fontana copy of Prince Heathen on the spot. It was an instance of financial recklessness that I have never regretted because this song has stayed with me ever since and with the passage of the years I have come to understand and appreciate it in different ways, for example, variously as a feminist, political and philosophical statement. This psychological drama is like a full-length feature film. From Prince Heathen (Topic TSCD344, 1994)

Small print

The image of Brass Monkey from the Goose Is Out, Dog Kennel Hill, London on 15 February 2009 is © Santosh Sidhu. The copyright of all other images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers.

2. 5. 2011 |

read more...

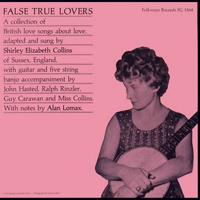

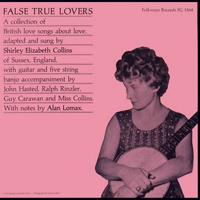

[by Ken Hunt, London] This concluding section departs from the previous structure. In this coda Shirley Collins compares then and now. She recollects what it was like starting out for her, with the recording of her first two LPs Sweet England (1959) and False True Lovers (1960) back-to-back in 1958. With Alan Lomax and Peter Kennedy presiding, she cut the tracks for those two records over two days in a house in the north London residential district of Belsize Park. She reflects on what is happening now, especially her concerns about fast-tracked success and its disadvantages.

[by Ken Hunt, London] This concluding section departs from the previous structure. In this coda Shirley Collins compares then and now. She recollects what it was like starting out for her, with the recording of her first two LPs Sweet England (1959) and False True Lovers (1960) back-to-back in 1958. With Alan Lomax and Peter Kennedy presiding, she cut the tracks for those two records over two days in a house in the north London residential district of Belsize Park. She reflects on what is happening now, especially her concerns about fast-tracked success and its disadvantages.

“I think it was quite spontaneous, a lot of it. Those two albums were recorded in two days. Everything was probably just done once, possibly twice if I made a great mistake. I just made up the next song as it came to it. At that time I was very naïve and I hadn’t been recorded like that before. In a way it was like a field recording, although done indoors in a studio. I was just singing the songs as they came up. Some of them had to be more thought about because other people were accompanying me on them. I don’t think we thought in advance because I know when all the recordings were made they were then divided up into the Folkways tracks and the Argo English choices. It wasn’t pre-planned. There was not that degree of sophistication or forethought then. It was quite spontaneous.

“I think it was quite spontaneous, a lot of it. Those two albums were recorded in two days. Everything was probably just done once, possibly twice if I made a great mistake. I just made up the next song as it came to it. At that time I was very naïve and I hadn’t been recorded like that before. In a way it was like a field recording, although done indoors in a studio. I was just singing the songs as they came up. Some of them had to be more thought about because other people were accompanying me on them. I don’t think we thought in advance because I know when all the recordings were made they were then divided up into the Folkways tracks and the Argo English choices. It wasn’t pre-planned. There was not that degree of sophistication or forethought then. It was quite spontaneous.

“None of us was used to recording anyway. We weren’t used to using microphones. I think you were always very nervous when you were being recorded as well. I remember feeling quite scared of the whole procedure.

“Nowadays you can record in your own kitchen or front room. Anyone can do it. I think anyone reading about how nervous one would be about doing it, would think, ‘Nah, it’s easy.’ It wasn’t then and I was recording for two rather important people. They were very encouraging. When I listen back to it, there really were some tracks on there that were quite lovely. And some that are quite dreadful; the songs aren’t worth being recorded. But it was typical of my repertoire at the time and typical of what I’d learned from home, so it was an honest record.”

If you were soaking up a song then, assimilating it and making it something of your own, if you like, what sort of length of time would that process have taken for you in those days? The reason I ask is I get the feeling with a number of singers nowadays that they are too quick off the mark recording songs. They’re not under the skin of the song.

If you were soaking up a song then, assimilating it and making it something of your own, if you like, what sort of length of time would that process have taken for you in those days? The reason I ask is I get the feeling with a number of singers nowadays that they are too quick off the mark recording songs. They’re not under the skin of the song.

“To be fair, I think that’s pretty much me for my first two. I wasn’t ready. They were too early. The songs weren’t good enough really. A great many of them were trivial and when I look back at them now I do cringe. But I think the difference between me then is that we didn’t have all the information behind us that the singers today should have. If they express an interest in traditional song, they should be prepared to listen to the traditional singers.

“I think you’re right. I think a lot of them are recording too soon. It’s understandable because if you want to make a career of singing you want to get going fairly quickly. Because they receive so much praise for their recording – they’re either the Best New Album of the Year or the Best Songwriter, Best Song or Best Folksinger – they’ve got to come up with the Best every year. You got so many Bests out there that it’s difficult to pick out the Best now. Not enough of them are listening to enough of the traditional singers that they should be listening to. You’ve got to listen to your Harry Coxs, your Phoebe Smiths, your Caroline Hughes, your Harry Uptons and your Coppers; you’ve just got to. How can you be a singer of traditional song if you haven’t formed any basis in the real thing and you’re acquiring songs the easy way from what the Revival singers were singing? And some of the Revival singers weren’t picking up from proper sources either, you know, from the best of the singers.

“So, in some cases the new singers are picking up ‘double-poor’: they’re not learning from the best. They’re doing it the easy way. There’s not enough hard work in there. They can play instruments like mad. They’re very good instrumentalists. But they’re not listening to the songs: they’re listening to themselves singing the songs. It’s so apparent when you listen to: they want to sound like either Sandy Denny or Kate Rusby. Sandy wasn’t a traditional singer. Wonderful singer, wonderful songwriter and great in that genre but not in folk music. Half the girls are singing like children, like little girls whispering into the microphone. The music is more robust than that. Even though a lot of the songs are tender and romantic, there’s still a wonderful robustness about them. Melancholy yes, but there’s still strength in there too. That seems to be missing from a lot of the modern performances. It’s what I feel.”

For more information go to www.shirleycollins.co.uk

For information about the discographical output and song material of Shirley Collins, Martin Carthy, Anne Briggs, Nic Jones and their kind, set aside a couple of hours to browse Reinhard Zierke’s labour of love and folk disquisition. Begin with Shirley at: www.informatik.uni-hamburg.de/~zierke/shirley.collins/index.html

Small print

The copyright of all other images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers. Unless otherwise stated, all interview material is original and copyright Ken Hunt.

25. 4. 2011 |

read more...

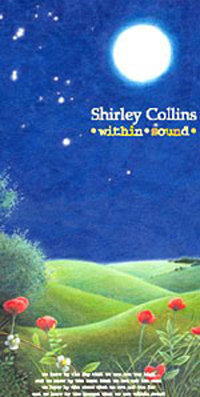

[by Ken Hunt, London] In this second part we pick up the story of the out-of-print classic retrospective Within Sound at a point after the 1970 masterpiece Love, Death & The Lady (1970).

[by Ken Hunt, London] In this second part we pick up the story of the out-of-print classic retrospective Within Sound at a point after the 1970 masterpiece Love, Death & The Lady (1970).

Despite everything in the years from 1955, when Shirley Collins had first appeared on record, to 1970 , there was no grand plan behind the continually shape-shifting projects that she was delivering. “I have to say,” she explains. “it ‘happened’ rather than it was planned in advance that one would do something different the whole time. Things did evolve. It was the discoveries. It was those fortunate meetings. It was my own interests in the sorts of music I liked listening to – Early Music, for example – that led me into these other things. In a way it did just grow. It wasn’t planned but it wasn’t willy-nilly. There was obviously a great deal of thought involved with each record once we decided to do the recording we were doing. I think it’s possibly because my personal life and my singing life were so bound up that whatever was going on in my life was reflected in the records as well. The influences, the things that were happening, the people I met as I went along… It’s all rather fortunate the way things happened. Like finding the Early Musicians in Musica Reservata and meeting David Munrow. But then, I suppose, it was having the wit to think that this and that would work together. With part of the early stuff it was John Marshall who thought that we could do it; it was Dolly who wrote the stuff and made it happen with her arrangements; and it was my ear and my own inclinations to do the best for the music.

Despite everything in the years from 1955, when Shirley Collins had first appeared on record, to 1970 , there was no grand plan behind the continually shape-shifting projects that she was delivering. “I have to say,” she explains. “it ‘happened’ rather than it was planned in advance that one would do something different the whole time. Things did evolve. It was the discoveries. It was those fortunate meetings. It was my own interests in the sorts of music I liked listening to – Early Music, for example – that led me into these other things. In a way it did just grow. It wasn’t planned but it wasn’t willy-nilly. There was obviously a great deal of thought involved with each record once we decided to do the recording we were doing. I think it’s possibly because my personal life and my singing life were so bound up that whatever was going on in my life was reflected in the records as well. The influences, the things that were happening, the people I met as I went along… It’s all rather fortunate the way things happened. Like finding the Early Musicians in Musica Reservata and meeting David Munrow. But then, I suppose, it was having the wit to think that this and that would work together. With part of the early stuff it was John Marshall who thought that we could do it; it was Dolly who wrote the stuff and made it happen with her arrangements; and it was my ear and my own inclinations to do the best for the music.

“In a way it harks back to what Alan always believed. Alan Lomax always believed that you put the best at the disposal of the people you were recording. He went for the best: the best technical quality you could get, the best recording equipment – and it was being improved the whole time. He always had to do the best for the people that he was recording. And I always felt that I had to do the best for the music. The best was, in many cases, to get a perfect accompaniment. Or if not perfect, an appropriate accompaniment for this lovely music that had been neglected for so long. I was fortunate to have a sister that could write it, and people around me that were encouraging. God knows, it didn’t get a lot of encouragement but there were key people!”

She volunteers their names without prompting. “I was fortunate to meet Lomax in the first place. John Marshall was another. He supported and encouraged me, and was always trying to find other ways of doing things – although they were tiresome at times as well. He was always willing and open to try things. I was fortunate later to meet Ashley. I was fortunate to have David Tibet come on the scene; he put out the first compilation of the Topic stuff. I was incredibly fortunate to have David Suff as a champion. I was absolutely blessed with these keen figures but then I also think they were also blessed with me.”

She volunteers their names without prompting. “I was fortunate to meet Lomax in the first place. John Marshall was another. He supported and encouraged me, and was always trying to find other ways of doing things – although they were tiresome at times as well. He was always willing and open to try things. I was fortunate later to meet Ashley. I was fortunate to have David Tibet come on the scene; he put out the first compilation of the Topic stuff. I was incredibly fortunate to have David Suff as a champion. I was absolutely blessed with these keen figures but then I also think they were also blessed with me.”

Recovering from a small fit of the giggles, she continues, “I’ve stopped being so modest nowadays because when I listen to the stuff I know it’s so good. I’m not going to sit back and pretend that it’s not now.”

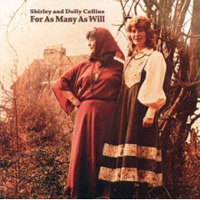

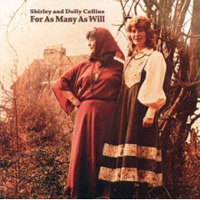

Part of the problem to do with her phasing out performing in public was a loss of confidence. In 1978 Topic released For As Many As Will, co-credited to her sister Dolly. Two years later on an Australian tour in early 1980, a double-hander with Peter Bellamy (formerly of the Young Tradition), she plagued herself with doubts – and self-inflicted doubts are amongst the worst . It had further repercussions for her singing. She remembers Australia as “being a terrifying ordeal because I didn’t have Dolly and I was losing my voice. It was part of this slow process of everything going and the more I did the more afraid I became. The Sydney Opera House was terrifying. When I listened to Come, My Love it was absolutely gorgeous. There was Dolly’s wonderful arrangement played with such bravura on the harpsichord by Winsome Evans that I thought, ‘You were all right, you could have kept on doing this, Shirl!’ But I didn’t hear this at the time. I wasn’t aware at the time that it was more than OK. I let myself believe that I was no good anymore. I loved English music and I wanted to be a singer of English songs. However hard it got, I never gave in. Until things got too impossible for me to be able to sing, that is. By that time, I’d already virtually done it really, I think against all the odds. I hoodwinked myself. Or perhaps I punished myself.”

Part of the problem to do with her phasing out performing in public was a loss of confidence. In 1978 Topic released For As Many As Will, co-credited to her sister Dolly. Two years later on an Australian tour in early 1980, a double-hander with Peter Bellamy (formerly of the Young Tradition), she plagued herself with doubts – and self-inflicted doubts are amongst the worst . It had further repercussions for her singing. She remembers Australia as “being a terrifying ordeal because I didn’t have Dolly and I was losing my voice. It was part of this slow process of everything going and the more I did the more afraid I became. The Sydney Opera House was terrifying. When I listened to Come, My Love it was absolutely gorgeous. There was Dolly’s wonderful arrangement played with such bravura on the harpsichord by Winsome Evans that I thought, ‘You were all right, you could have kept on doing this, Shirl!’ But I didn’t hear this at the time. I wasn’t aware at the time that it was more than OK. I let myself believe that I was no good anymore. I loved English music and I wanted to be a singer of English songs. However hard it got, I never gave in. Until things got too impossible for me to be able to sing, that is. By that time, I’d already virtually done it really, I think against all the odds. I hoodwinked myself. Or perhaps I punished myself.”

Going through the possible material for inclusion on Within Sound no longer involved breast- or brow-beating. The passage of the years had taught her the lesson not to judge herself as harshly as once she had. “There were certain things, like The False True Love that I’d recorded twice in my life, where I thought how brave a performance it was when I listened to it. That was the actual word. I hold one note and it just goes on. I was always in love or suffering. I think it has the essence of young, unrequited love in it. I thought, ‘God, that’s a brave performance!'”

This process of rediscovery threw up several insights too. “There are other things that you listen to – Poor Murdered Woman, which I think is one of the great tracks – which have great passion in them. It’s not so passionate that it’s dramatised. The passion is within the song itself. It’s a very restrained sort of passion. When I hear Poor Murdered Woman I think, that’s good. There are so many funny things too. Like, when you listen to Fare Thee Well, My Dearest Dear there’s Ashley’s bass louder than my voice. And I think that’s fairly typical. It makes me laugh but I had to put it on the boxed set because that’s such an important song to me and Harriet Verrall of Monksgate was such an important singer to me.”

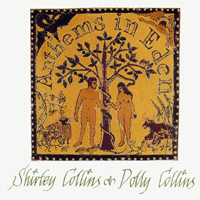

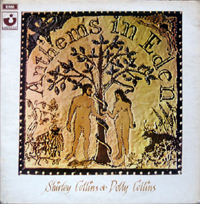

With Within Sound surprises came in other packages too. One of the pieces that rings so sonorously down the years is the unearthing of Whitsun Dance. Unlike the ‘big band’ rendition from the finished Anthems In Eden (1969), on the boxed set she sings it alone with her sister accompanying on piano. Adding an insight into the creativity, it wafts in the refreshing tang of something familiar yet somehow unfamiliar. “That was obviously a trial recording of the piece. I didn’t know I had it. It came from the cupboard under the stairs. I got a box of tapes and we kept looking and looking. There was this thing that said Whitsun Dance. I thought it was bound to be an Anthems track. It was recorded in the studio, I don’t remember for certain, a day or so before. It is lovely. I was so thrilled when I heard it because it has a different quality and a slightly different lift to the tune. I hadn’t realised what I’d done. I was so thrilled by that little discovery. It’s only a slight difference but it’s a huge difference.”

With Within Sound surprises came in other packages too. One of the pieces that rings so sonorously down the years is the unearthing of Whitsun Dance. Unlike the ‘big band’ rendition from the finished Anthems In Eden (1969), on the boxed set she sings it alone with her sister accompanying on piano. Adding an insight into the creativity, it wafts in the refreshing tang of something familiar yet somehow unfamiliar. “That was obviously a trial recording of the piece. I didn’t know I had it. It came from the cupboard under the stairs. I got a box of tapes and we kept looking and looking. There was this thing that said Whitsun Dance. I thought it was bound to be an Anthems track. It was recorded in the studio, I don’t remember for certain, a day or so before. It is lovely. I was so thrilled when I heard it because it has a different quality and a slightly different lift to the tune. I hadn’t realised what I’d done. I was so thrilled by that little discovery. It’s only a slight difference but it’s a huge difference.”

What emerges over the course of Within Sound is the distillation of something uniquely English. Folksong isn’t everybody’s cup of tea – nothing is, thank goodness – but some of that is because too many people have come to the table with their minds made up about singers with cupped hand over the ear. (Far from being folk’s exclusive domain or folly, it is a technique used in voice projection round the globe.) Naturally, folksong must have had its moments of Moon-in-Junery but folk music’s oral process is an extremely efficient way of disposing of banality as well as preserving the stuff that touches the soul. After all, a shit song need not be a shit song forever; it can be relegated to the antiquarian’s back pages and quietly parked. It’s the good stuff that we remember and that is what we need to remember.

With Within Sound, part of England’s rich folk tradition began to receive the attention it deserves.

A coda

A coda

Harriet Verrall, it should be explained, was the original source of Poor Murdered Woman on Shirley Collins and the Albion Country Band’s No Roses (1971) and the well-known tune to Our Captain Cried All Hands, a piece of music that Ralph Vaughan Williams re-christened Monksgate when setting John Bunyan’s rousing school assembly ‘favourite’, He Who Would Valiant Be in The English Hymnal published in 1906 for the Church of England under the editorship of Percy Dearmer and Ralph Vaughan Williams. Parethetically, the whole Verrall-Vaughan Williams axis figures in her recent talk A Most Sunshiny Day that she performs with actor-singer Pip Barnes.

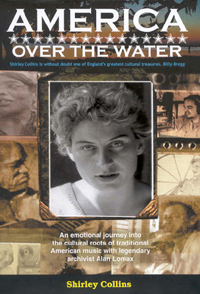

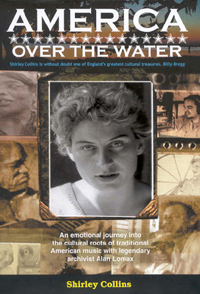

Although she lost her singing voice, she bounced back with a series of talks that range over her work with Alan Lomax (also the subject of her autobiographical account of their 1959 music-collecting trip America Over The Water (2004)), accounts of Southern English Gypsies and, as ever with Pip Barnes, supporting Martyn Wyndham-Read in his account, Down The Lawson Trail – his portrait in words and song of the Australian writer and bush poet Henry Lawson (1867-1922).

For more information go to www.shirleycollins.co.uk

Ken Hunt is the author of the biographical essays about Dolly Collins (1933-1995) and Davey Graham (1940-2008) in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Small print

The copyright of all other images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers. Unless otherwise stated, all interview material is original and copyright Ken Hunt.

18. 4. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Folksong, English, Czech, Hungarian or any other, is all human life in a nutshell distilled, confined or liberated through song. The Sussex singer Shirley Collins’ achievement is unmatched in the annals of twentieth-century folk music anywhere. Blessed with a voice a natural as breathing, she succeeded in bottling and freeing the essence of the songs she sang. When Shirley Collins’ Within Sound appeared in 2002, the boxed retrospective treatment was a relatively new development in folk music. It is utterly appropriate that Shirley Collins should have been Britain’s first female folk singer to get the long-box treatment. Joan Baez’s Rare, Live and Classic (1993) got the US honours in the female folkie category. Shirley Collins got it with the now sold-out Within Sound (Fledg’ling NEST 5001, 2002).

[by Ken Hunt, London] Folksong, English, Czech, Hungarian or any other, is all human life in a nutshell distilled, confined or liberated through song. The Sussex singer Shirley Collins’ achievement is unmatched in the annals of twentieth-century folk music anywhere. Blessed with a voice a natural as breathing, she succeeded in bottling and freeing the essence of the songs she sang. When Shirley Collins’ Within Sound appeared in 2002, the boxed retrospective treatment was a relatively new development in folk music. It is utterly appropriate that Shirley Collins should have been Britain’s first female folk singer to get the long-box treatment. Joan Baez’s Rare, Live and Classic (1993) got the US honours in the female folkie category. Shirley Collins got it with the now sold-out Within Sound (Fledg’ling NEST 5001, 2002).

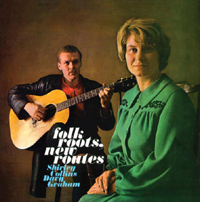

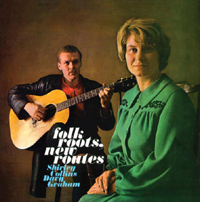

Over the course of her eventful career, Shirley Collins, born in August 1935, had any number of peers but very few equals when it came to England’s folk scene and astonishingly few questionable moments on vinyl. She may have experimented with Irish and American song forms early on (though her inflexions wavered at times on say, Jane, Jane on her and Davey Graham’s co-credited Folk Roots, New Route also anthologised on Argo’s spoken word and music set, Voices), but she never dropped her Southern English accent – as if she could ever get Sussex out of her bloodstream. Within Sound made her achievement and progress patently clear. It need not be said, but let’s say it anyway: Fledg’ling Record’ David Suff and Shirley Collins had a huge body of work to draw upon, and a massive task before them, when cherry-picking the performances that made it to final mastering.

For her, part of the joy inherent in the selection process was rediscovering the worth of and joy in what she had done. “I always knew that The Plains of Waterloo was a great song but it’s a great recording of it too. It’s lovely,” she smiles, “that you can still surprise yourself with your own performance. That’s a bonus.”

On Within Sound, complementing Collins’ official releases on the Argo, Collector, Deram, Folkways, Harvest, HMV, Island, Polydor and Topic labels, is a smattering of judiciously chosen studio and live performances never, if ever, heard by the wider public, since the day she breathed life into them. Chronologically organised, Within Sound takes the listener on an aural journey from Dabbling In The Dew drawn from the various artists’ anthology Folk Song Today (HMV, 1955), and her double LP debut with Sweet England (1959) for Argo in Britain and False True Lovers (1960) for Folkways in the United States – a phenomenal feat at the time – to Lost In A Wood, drawn from Martyn Wyndham-Read’s brainchild, Song Links (Fellside, 2003), a visionary examination setting British and Australian variants of folksongs next to each other.

On Within Sound, complementing Collins’ official releases on the Argo, Collector, Deram, Folkways, Harvest, HMV, Island, Polydor and Topic labels, is a smattering of judiciously chosen studio and live performances never, if ever, heard by the wider public, since the day she breathed life into them. Chronologically organised, Within Sound takes the listener on an aural journey from Dabbling In The Dew drawn from the various artists’ anthology Folk Song Today (HMV, 1955), and her double LP debut with Sweet England (1959) for Argo in Britain and False True Lovers (1960) for Folkways in the United States – a phenomenal feat at the time – to Lost In A Wood, drawn from Martyn Wyndham-Read’s brainchild, Song Links (Fellside, 2003), a visionary examination setting British and Australian variants of folksongs next to each other.

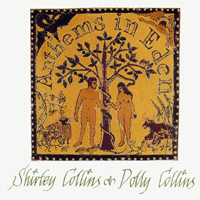

Within Sound contains plenty of the revelations we have come to expect of boxed sets. For example, the run-through of Whitsun Dance – a recording pre-dating her and her arranger-composer sister Dolly Collins’ sessions proper for their 1969 opus magnum Anthems In Eden – is the stuff of dreams. Likewise, the inclusion of her first husband, Austin John Marshall’s song Honour Bright from the never-realised but partially recorded ballad opera The Anonymous Smudge.

As to other comparisons of the creative nature, there is Just As The Tide Was Flowing, as Shirley Collins quips, available “in its three lives” in versions recorded or released in 1959, 1971 and 1979. These were “the straightforward one as we learned from Aunt Grace, then the one with the Albion Country Band and finally a nice arrangement of Dolly’s.” Shirley explains, “That’s an important song because it’s one song that came direct from the family. Nobody else had it [in that version]. If other people sang it they had it in a much rounder form. I still get letters from people saying, ‘You know Just As The Tide Was Flowing; did you know it’s got fourteen more verses?’ My Aunt Grace only knew two verses, so that’s how we sang it.”

Within Sound‘s chronological sequencing makes many things plain, most particularly her development. Beginning near the beginning and treating her first two apprentice pieces, Sweet England and False True Lovers as a single piece of work – they were recorded them back-to-back in one recording session under the watchful eyes of Alan Lomax and Peter Kennedy and then the tracks were divvied up – the listener gets a good feel for the extent of change from one album to the next. Although other work appeared out of sequence, notably the Collins Sisters’ collaboration with the Young Tradition, The Holly Bears The Crown (only finally released in 1995, long after the Young Tradition had broken up in 1969), the official releases between Sweet England and False True Lovers and For As Many As Will (1978) – the final album released under her own name, after which a form of dysphonia stole her singing voice – bear that out.

Between those years, she achieved much of worth. Her second husband, Ashley Hutchings played a prominent part, involving her with the likes of the Morris On bunch, the Etchingham Steam Band, the Albion Dance Band and the Albion Band. Whereas so many folk acts made essentially the same album again and again and again, Shirley Collins showed a steady advance and little or no stylistic repetition once she was recording LPs – and that first release was, remember, in 1959.

She had begun accompanying herself on autoharp or banjo, perhaps augmented with somebody like the physicist John Hasted on guitar. It was all very much in the Fifties’ style of presenting folksong and very much in the stamp of the times. By the time she made The Sweet Primeroses (1967) – ‘primerose’ is a dialect or variant spelling of the commoner ‘primrose’, for the English primrose (Primula vulgaris) – she had five EPs to her name, that collaborative LP with the guitarist Davey Graham (Folk Roots, New Routes, 1964) and a lot of journeyman work to her name and behind her. The Sweet Primeroses was a landmark, not only because it marked the recording debut of her arranger-accompanist-composer sister Dolly on portative pipe organ but because it was one of the albums that stood apart from the trend of the times.

She had begun accompanying herself on autoharp or banjo, perhaps augmented with somebody like the physicist John Hasted on guitar. It was all very much in the Fifties’ style of presenting folksong and very much in the stamp of the times. By the time she made The Sweet Primeroses (1967) – ‘primerose’ is a dialect or variant spelling of the commoner ‘primrose’, for the English primrose (Primula vulgaris) – she had five EPs to her name, that collaborative LP with the guitarist Davey Graham (Folk Roots, New Routes, 1964) and a lot of journeyman work to her name and behind her. The Sweet Primeroses was a landmark, not only because it marked the recording debut of her arranger-accompanist-composer sister Dolly on portative pipe organ but because it was one of the albums that stood apart from the trend of the times.

Whereas the popular face of folk was the smiles and serious faces of television’s Julie Felix, the Spinners and their ilk, Shirley sang Sussex; much like the Watersons sang Yorkshire or Harry Boardman sang Lancashire. A year on and Shirley Collins was making The Power of the True Love Knot (1968), still credited solely to her but with Dolly’s adventuresome arrangements and accompaniments ever more to the fore.

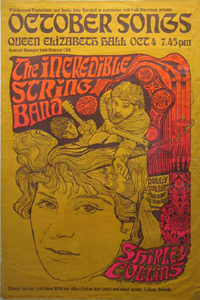

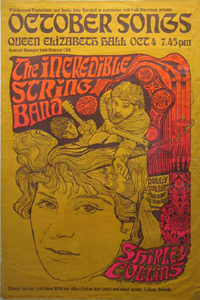

Dolly Collins defined her approach succinctly to me in 1979 for an article in Swing 51: “Let the music be suited to the people [the audience] rather than the people be ‘trained’ to the music”; these were words that her teacher, the composer and doyen of the Workers’ Music Association Alan Bush (1900-1995) might have dictated to her. The Power of the True Love Knot‘s opener, Bonnie Boy uses the cello of Bramwell ‘Bram’ Martin, the cellist on the Beatles’ Eleanor Rigby and She’s Leaving Home but also a mainstay of the ‘Mantovani Sound’, as a colour instrument while Mike Heron and Robin Williamson of the Incredible String Band did their finger-popping stuff on the bonnily romantic, let’s-outdo-Mills & Boon Ritchie Story. (Both tracks are fragrances on Within Sound.) By now, you realised that you were somewhere completely unimaginable at the time of Sweet England. This is less surprising when you know that Austin John Marshall was an early advocate of Jimi Hendrix and had taken Shirley off to see him early on. It was a period of exemplary artistic foment.

Next she asked her audience to take a deep breath and a leap into the unknown with Anthems In Eden. 1969 was the year of Martin Carthy and Dave Swarbrick’s defining Prince Heathen, Ralph McTell’s Spiral Staircase, Judy Collins’ Who Knows Where The Time Goes, Joan Baez’s Any Day Now, Fairport Convention’s Liege and Lief, and the Spinners’ never-better-titled Not Quite Folk. The Sisters’ Early Music, big band album stood out and apart from the throng. Furthermore, it was released in the launch year of EMI’s ‘progressive’ label Harvest. It would sit alongside era-defining work by Pink Floyd, Forest, the Edgar Broughton Band and Deep Purple. Its first side, a complete song-cycle, had first been aired on BBC Radio 1’s My Kind of Folk in August 1968 with the Home Brew and the Dolly Collins Harmonious Band supporting. This, the first of two albums for the ‘underground label’, reached places and audiences denied Radio 1.

Next she asked her audience to take a deep breath and a leap into the unknown with Anthems In Eden. 1969 was the year of Martin Carthy and Dave Swarbrick’s defining Prince Heathen, Ralph McTell’s Spiral Staircase, Judy Collins’ Who Knows Where The Time Goes, Joan Baez’s Any Day Now, Fairport Convention’s Liege and Lief, and the Spinners’ never-better-titled Not Quite Folk. The Sisters’ Early Music, big band album stood out and apart from the throng. Furthermore, it was released in the launch year of EMI’s ‘progressive’ label Harvest. It would sit alongside era-defining work by Pink Floyd, Forest, the Edgar Broughton Band and Deep Purple. Its first side, a complete song-cycle, had first been aired on BBC Radio 1’s My Kind of Folk in August 1968 with the Home Brew and the Dolly Collins Harmonious Band supporting. This, the first of two albums for the ‘underground label’, reached places and audiences denied Radio 1.

Creatively it was a high water mark that she wisely never attempted to reach again. That was not in her nature. Beside the buoyancy and big-budget values of Anthems In Eden, Love, Death & The Lady (1970) seemed a bare affair, reflecting in part its leading ladies’ wretchedness in matters of the heart. Plains of Waterloo captures a rarely paralleled quality of a sombre bleakness and hopelessness. Following Love, Death & The Lady, she returned with No Roses (1971), co-credited to the Albion Country Band, an album with a crew of folk-rock and wayward folk alumni that included Ashley Hutchings on bass, Dave Mattacks on drums, Richard Thompson on guitar, vocalists Maddy Prior (of Steeleye Span) and Royston Wood (late of the Young Tradition), Lal and Mike Waterson. By Adieu To Old England (1975) and For As Many As Will (1978), Shirley and Dolly Collins had gone back to acoustically rooted sensibilities. If the listener picks three (or five) of these albums sequentially starting anywhere in the chronological order, the degree of stylistic difference is astounding. The one constant is her voice. It rarely veered from its Sussex roots.

Creatively it was a high water mark that she wisely never attempted to reach again. That was not in her nature. Beside the buoyancy and big-budget values of Anthems In Eden, Love, Death & The Lady (1970) seemed a bare affair, reflecting in part its leading ladies’ wretchedness in matters of the heart. Plains of Waterloo captures a rarely paralleled quality of a sombre bleakness and hopelessness. Following Love, Death & The Lady, she returned with No Roses (1971), co-credited to the Albion Country Band, an album with a crew of folk-rock and wayward folk alumni that included Ashley Hutchings on bass, Dave Mattacks on drums, Richard Thompson on guitar, vocalists Maddy Prior (of Steeleye Span) and Royston Wood (late of the Young Tradition), Lal and Mike Waterson. By Adieu To Old England (1975) and For As Many As Will (1978), Shirley and Dolly Collins had gone back to acoustically rooted sensibilities. If the listener picks three (or five) of these albums sequentially starting anywhere in the chronological order, the degree of stylistic difference is astounding. The one constant is her voice. It rarely veered from its Sussex roots.

For more information go to www.shirleycollins.co.uk

Small print

The copyright of all other images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers. Unless otherwise stated, all interview material is original and copyright Ken Hunt.

11. 4. 2011 |

read more...

[Ken Hunt, London] It can be really beastly to be separated from kith and kin on the treasured island. But then one casts one’s eye around and one realises that those waterside plants aren’t all hemlock water dropwort, mugworts, figworts etc. There are the mangoes, for example. And the flamingos don’t always get away with raiding the mango orchard, though barbecued flamingo can grow fair tiresome. Instead one dons the fiesta clobber and dances like a demented chap to the music of Aruna Sairam, Robb Johnson, Tommy McCarthy, Dresch Quartet, Lily Allen, Bhimsen Joshi, Rendhagyó Prímástalálkozó, Françoise Hardy, Traffic and Robb Johnson again. It keeps the flaming, raiding flamingos out the orchard if nothing else.

[Ken Hunt, London] It can be really beastly to be separated from kith and kin on the treasured island. But then one casts one’s eye around and one realises that those waterside plants aren’t all hemlock water dropwort, mugworts, figworts etc. There are the mangoes, for example. And the flamingos don’t always get away with raiding the mango orchard, though barbecued flamingo can grow fair tiresome. Instead one dons the fiesta clobber and dances like a demented chap to the music of Aruna Sairam, Robb Johnson, Tommy McCarthy, Dresch Quartet, Lily Allen, Bhimsen Joshi, Rendhagyó Prímástalálkozó, Françoise Hardy, Traffic and Robb Johnson again. It keeps the flaming, raiding flamingos out the orchard if nothing else.

Kārthikēya – Aruna Sairam

One of the most consistently coruscating female vocalists in the South Indian tradition, Aruna Sairam presents a master-class in melody matched to vocal rhymicality on this double CD. The piece is set in Valaci and in the ādi rhythm cycle. Her performance is brilliantly understated and is accompanied by Embar Kannan on violin, P. Sathish Kumar on mridangam (double-headed barrel drum) and Dr S. Karthick on ghatam (tuned clay pot). The violin ornamentations and solo responses are superb. That said, this entire release is inspiring. From Gāyāka Vāggēyakārās (Rajalakshmi Audio RACDV 08249/50, 2008)

Not an advert but a recommended source for South Indian music is Celextel Enterprises Pvt. Ltd. in Chennai – www.celextel.com – which greatly undercuts prices outside India where prices ratchet up scandalously.

The Young Man With The Girlfriend & Guitar – Robb Johnson

The Young Man With The Girlfriend & Guitar – Robb Johnson

Richard Williams’ obituary of Suze Rotolo in The Guardian set me off a spiralling train of thought. Coincidentally I had only begun reading her autobiography, A Freewheelin’ Time (2008) a fortnight before. I did copy-editing on Robb Johnson’s Clockwork Music: maybe that’s why its lyrics are deeper within me than many of his other albums. The title gives the scenario away. He sings, “She’s hanging on his arm & every word/Like they were poetry/Just like Suze Rotolo in 1963.”

It struck me as fascinating that an album cover image had done and meant so much. Then Bonnie Dobson sent me a link to something one of her friends, Susan Green had written about Suze Rotolo called ‘Fifty-Two Years and Countless Cats: Good-Bye, My Friend.’ So, this song sparked a concatenation of associations sealed with a farewell kiss. From Clockwork Music (Irregular IRR048, 2003)

Susan Green’s memories of her friendship with Suze Rotolo are at: http://www.criticsatlarge.ca/2011/03/fifty-two-years-and-countless-cats-good.html

Down That Road – Tommy McCarthy

At Prague’s Khamoro 2003: World Roma Festival I had the chutzpah to do a talk about Scottish Traveller culture within the quite separate Roma (Gypsy) context. It was a talk that arced between Scotland’s intertwined yet different Roma and Traveller cultures with a few Punjabi linguistic connections strewn here and there. I cannot say whether I would have expanded the talk and taken it further afield to Ireland had I known about Tommy McCarthy. I might have spoken more about John Reilly, an unaccompanied singer based largely in Co. Roscommon in Éire whose LP The Bonny Green Tree (1978) on Topic remains one of my twenty most favourite LPs of traditional music ever to emerge from the British Isles in its geographical, as opposed to geo-political sense.

My old friend Hans Fried, the son of the Austrian poet Erich Fried, was the first person to hosanna Tommy McCarthy in my earshot. After five decades of friendship and ping-ponging cultural inspirations to and fro I figure he still knows more than me. So, anyway, Hans said to listen and so I did. This is the first song on the album and it jumped out and lit a powder trail to explosive future discoveries. Ron Kavana produced and engineered. From Round Top Wagon (ITCD 001, 2011)

Bánat, Bánat – Dresch Quartet

Nigh on ten minutes of Hungarian folk-jazz with a J.S. Bach beat on a theme of ‘Sorrow, Sorrow’, originally released on their album Révészem, Révészem (‘Ferryman, My Ferryman’). For the sheer vibe they capture. From A Népzenétől a Világzenéig 2 From Traditional to World Music (Folk Európa Kiadó FECD 037, 2010)

The Fear – Lily Allen

The Fear – Lily Allen

It’s a great, joyful, rip-snorting song that distils so much about contemporary society. It’s about packing plastic and not caring about consequences (“And I’ll take my clothes off and it will be shameless/Cause everyone knows that’s how you get famous”). It’s about fame, no longer knowing or caring about reality (“And I don’t know how I’m meant to feel anymore”) and riding roughshod over anyone in the way of achieving those goals. The wit of the lyrics is counterbalanced musically, once the nylon-strung guitar fades out, by the (I hope), deliberately jejune sound palette and relatively uncomplicated mix. But there again I’ve been wrong before. No matter, lyrically it is nuanced and amusing. From It’s Not Me, It’s You (Redial 5099969427626, 2009)

Yeh Tun Mundna – Bhimsen Joshi

I have no idea where Bhimsen Joshi released this gem. It is a poem by Kabir, the weaver, philosopher and mystic. In its aphoristic simplicity it ranks as one of the finest pieces on the human condition, the cycle of life and death and treating others ethically. In rough translation, it goes something like this:

“The body is brittle [transient]

One day you will be one with the dirt.

Says dirt to the potter,

‘Why do you dig me?

The day will come when I shall bury you.’

The wood says to the carpenter,

‘Why do you put holes in me?

The day will come when I shall burn you.'”

Any steer on where Bhimsen Joshiji recorded this masterpiece gratefully received.

From http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fVFl9u_ZkTs

Ken Hunt’s obituary of the singer from The Independent of Tuesday, 25 January 2011 is at: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/bhimsen-joshi-singer-widely-regarded-as-the-greatest-exponent-of-indian-classical-vocal-music-2193228.html

Három széki dal – Rendhagyó Prímástalálkozó

The piece’s title translates as ‘Three songs from Szék’ and the ensemble’s name as ‘Primas Parade’. Ágnes Herczku and Éva Korpás are the vocalists singing solo or together. Róbert Lakotos plays viola and violin, Mihály Dresch flutes, László Mester viola and Róbert Doór double-bass. The piece is earthy and there is dirt under the nails of these musicians. In a good sense. From A Népzenétől a Világzenéig 3 From Traditional to World Music (Folk Európa Kiadó FECD 052, 2010)

L’amour ne dure pas toujours – Françoise Hardy

L’amour ne dure pas toujours – Françoise Hardy

The first happiness of the day gave way to regrets that love doesn’t last all in one year. Françoise Hardy delivered both Le premier bonheur du jour and L’amour ne dure pas toujours in 1963. (Of course, it’s a cheap link…) Whether it was a Golden Age of Francophone pop music or not is immaterial. It was a time when a generation stepped on the merry-go-round. Including Bob Dylan who penned a poem with her in mind for his Another Side of album. A Hammond B-3 extravaganza as well. Blink and you’ll miss the entire song at under two and a half minutes in total. From The Vogue Years (BMG Buda Musique 3017530, 2001)

Every Mother’s Son – Traffic

Re-visiting the DeLuxe reissue of Traffic’s John Barleycorn Must Die rammed home how psychologically complex this composition by Steve Winwood and Jim Capaldi is. It goes from the brooding to the ecstatic. It is taut, tense and plaintive in different ways on the live version recorded at the Fillmore East in New York City in November 1970. One of my albums of all time. But this is the original studio version. From John Barleycorn Must Die (Island 533 241-1, 2011)

The Day We All Said Stop The War – Robb Johnson

The Day We All Said Stop The War – Robb Johnson

On 15 March 2003 Central London got snarled up with protesters of every hue, faith, class and political persuasion. Well, nearly – “We even got a Liberal or two.” This was Robb Johnson’s response to the Stop the War march. Fittingly, he wrote it in Ilmenau in old East Germany. In the song he says, “We got […]/Placards that make you angry/Placards that make you laugh…” One of the banners that got the biggest laugh and the biggest response said, “I wish I was French!” On account of the cheese-eating surrender monkeys’ refusal to participate. And now there is another war with no discernible exit strategy and the French are participating. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. The more it changes, the more it’s the same old deal. From Clockwork Music (Irregular IRR048, 2003)

The copyright of all other images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers.

�

3. 4. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Giant Donut Discs® column in Swing 51 brought together a wide range of talent and one of the finest was Dagmar Krause. The bumper double issue 13/14 included a lengthy interview with her, but also her current list of Donuts. In the spirit of her choices back then, this “patchy list” as she called it (“Seems fine to us,” was appended in 1989), had next to no additional information; in that spirit there are no subsequent annotations. That feels right because hers is a no-nonsense approach to music.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Giant Donut Discs® column in Swing 51 brought together a wide range of talent and one of the finest was Dagmar Krause. The bumper double issue 13/14 included a lengthy interview with her, but also her current list of Donuts. In the spirit of her choices back then, this “patchy list” as she called it (“Seems fine to us,” was appended in 1989), had next to no additional information; in that spirit there are no subsequent annotations. That feels right because hers is a no-nonsense approach to music.

Industrial Drums – Anthony Moore

Model of Kindness – Peter Blegvad

Crusoe’s Landing – Cassiber

Tierra Humeda – Amparo Ochoa

By Julio Solórzano

Strange Fruit – Billie Holiday

Respect – Aretha Franklin

Stitch Goes The Needle – Sally Potter

By Lindsay Cooper

Suite No. 3 Kuhle Wampe – Hanns Eisler

The German Requiem – Brahms

© 1989, rejuvenated 2011 Swing 51

23. 3. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Journey’s Edge is a stepping-stone, a betwixt and between work. It captures Robin Williamson poised in midair or mid-dream skipping from the fading psychedelic sepia of The Incredible String Band and yet to land sure-footedly on the other shore. Though nobody knew that on Journey’s Edge‘s unveiling in 1977. That only became apparent with the Merry Band of American Stonehenge later that year and A Glint At The Kindling in 1978. Journey’s Edge was Williamson’s début solo release after the splintering of the ISB in late 1974. The ISB’s final flurry of creativity – many would have substituted ‘death throes’ – as evidenced by No Ruinous Feud (1973) and Hard Rope And Silken Twine (1974) and the half-remarkable, rarely remembered swansong films Rehearsal and No Turning Back (both 1974), had increasingly bled them of their heyday’s constituency. The thrill had gone. To be frank, Journey’s Edge represented something between foreboding and tenterhooks anticipation. Williamson rose to the challenge, as perhaps only he knew how far to go. Journey’s Edge is relocation music par excellence.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Journey’s Edge is a stepping-stone, a betwixt and between work. It captures Robin Williamson poised in midair or mid-dream skipping from the fading psychedelic sepia of The Incredible String Band and yet to land sure-footedly on the other shore. Though nobody knew that on Journey’s Edge‘s unveiling in 1977. That only became apparent with the Merry Band of American Stonehenge later that year and A Glint At The Kindling in 1978. Journey’s Edge was Williamson’s début solo release after the splintering of the ISB in late 1974. The ISB’s final flurry of creativity – many would have substituted ‘death throes’ – as evidenced by No Ruinous Feud (1973) and Hard Rope And Silken Twine (1974) and the half-remarkable, rarely remembered swansong films Rehearsal and No Turning Back (both 1974), had increasingly bled them of their heyday’s constituency. The thrill had gone. To be frank, Journey’s Edge represented something between foreboding and tenterhooks anticipation. Williamson rose to the challenge, as perhaps only he knew how far to go. Journey’s Edge is relocation music par excellence.

Journey’s Edge‘s tales of journeying and arrival recall his responses to moving from Scotland to the United States at the turn of the year, 1974 into 1975, and his lingering looks back to Europe. Plus the album is very much in the stamp of its time and place of origin with its jazz-funk into Bee Gees’ disco – quite unlike the sound of his first West Coast agglomeration or fling, the Far Cry Ceilidh Band. At a musicians’ party he ran into one of the mainstays of the Merry Band, Sylvia Woods – the deliverer of Journey’s Edge‘s opening flourish and statement of intent on Border Tango. She recalled in an interview in Swing 51 that their meeting happened in December 1975. Woods, under the influence of Alan Stivell had begun playing harp and had gone so far to travel to Waltons in Dublin to buy a harp and harp tutors. She crammed them, Stivell and Derek Bell’s harp playing with the Chieftains into her cranium. She also admitted that before meeting him at the party she had heard neither of Robin Williamson nor the Incredible String Band. But she was working at McCabe’s Guitar Shop on Pico Boulevard in Santa Monica, which doubled as one of the Los Angeles area’s famous folk clubs. It became one of the Merry Band’s regular gigs.

In January 1975 she and Williamson started welding something together, sucking two musicians in her circle, the banjoist Kevin Carr and fiddler Bill Jackson, into their orbit. They were soon replaced by, as it were, the band’s two other, core musicians, Christopher Caswell and Jerry McMillan. The benchmark Merry Band, as they became known, gave their début concert on the 4th of July 1976, thus turning a humdrum date into a memorable one, one that should forever be remembered. Regrettably, Williamson cannot remember where it was. That quartet remains a benchmark of excellence and in Williamson’s memory “a happy band”. They would play their final concert at McCabe’s in December 1979. Although they never told their audience it was their final concert, it went out over national public radio and was subsequently released as an album. “We changed a bit through all the albums,” Sylvia told me in 1980, “but we were the Merry Band with a couple of extra people for Journey’s Edge.”

Williamson’s relocation to Los Angeles led to a burst of creative activity of varying kinds. Much of it was, however, hard to obtain outside continental North America in that great pre-internet age when learning about what he was doing meant reading counter-culture music press and discovering small-circulation literary and music magazines – mine, Swing 51 (1979-1989), being but one. Parallel with sketching, developing and head-arranging the material on Journey’s Edge, he wrote two music tutors for the fiddle and penny whistle, had extracted material from his “surreal autobiography” or “lyric montage” Mirrorman’s Sequence published in the 1977 West Coast anthology Outlaw Visions – it also included the work of writer-composer Paul Bowles and the painter-illustrator Neon Park of Frank Zappa, David Bowie and Little Feat cover art repute – and that year’s co-written thriller called The Glory Trap published under the composite pen name Sherman Williamson.

Fictions, collusions and inventions of varying sorts were Williamson’s forte, he would be the first – or, as Mirrorman, last – to agree. The ISB had revelled in their psychedelic prayer, post-Gilbert and Sullivan silliness and ‘premature world music’ guises. Along the way, at their peak they were shifting enough units and generating enough influence to give Jimi Hendrix and The Supremes a run for their money. But Journey’s Edge is Williamson reaching out to something new, more homespun and – dare one invoke the O-word? – more organic and reaching for things older and more philosophical. Mythic Times captures Williamson claiming again his ancestors of choice and Red Eye Blues his personal Newfoundland while The Maharajah of Mogador is him reclaiming an ancestor for whom he had no choice in the matter, as the said Maharajah came from his wind-up gramophone boyhood. Journey’s Edge is no Childhood’s End. It is no Journey’s End either. It looks to the future. It looks to the past. It is Williamson captured in mid-flight and in trailing-cloud, as they say in Hindlish, air-dash.

December 2006

This is a hitherto unpublished, longer version of some notes written for a reissue that stalled. An expanded edition of Journey’s Edge is available as Fledg’ling FLED 3071 (2008).

More information at www.thebeesknees.com

21. 3. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] British folk music found a top drawer brass player, arranger and composer in Howard Evans. He had an utterly pragmatic, utterly professional attitude to music making and the musician’s life and from 1997, when he joined the Musicians Union’s London headquarters, as assistant general secretary for media he revealed that over and over again. He was totally pragmatic about his art and the first to drolly prick any bubbles of pretension about making music. He brought a wider knowledge and a greater diversity of musical experiences to bear on making music than any professional musician I ever met but he never got the slightest tan from the musical limelight.

[by Ken Hunt, London] British folk music found a top drawer brass player, arranger and composer in Howard Evans. He had an utterly pragmatic, utterly professional attitude to music making and the musician’s life and from 1997, when he joined the Musicians Union’s London headquarters, as assistant general secretary for media he revealed that over and over again. He was totally pragmatic about his art and the first to drolly prick any bubbles of pretension about making music. He brought a wider knowledge and a greater diversity of musical experiences to bear on making music than any professional musician I ever met but he never got the slightest tan from the musical limelight.

He mixed years of experience playing brass in military music contexts with the Welsh Guards, in pit orchestras, in London shows such as Cats, Starlight Express and Lou Reizner’s production of The Who’s Tommy and for sessions for the likes of the Star Wars soundtrack, Rick Wakeman, Emerson, Lake & Palmer Evans and the André Previn-era London Symphony Orchestra. Apart from the LSO, he played with the Royal Ballet, Welsh Opera and, most pertinently for his folk connections, with the National Theatre (NT) (as it was called before it got a ‘Royal’ appendage stuck at its front).

He mixed years of experience playing brass in military music contexts with the Welsh Guards, in pit orchestras, in London shows such as Cats, Starlight Express and Lou Reizner’s production of The Who’s Tommy and for sessions for the likes of the Star Wars soundtrack, Rick Wakeman, Emerson, Lake & Palmer Evans and the André Previn-era London Symphony Orchestra. Apart from the LSO, he played with the Royal Ballet, Welsh Opera and, most pertinently for his folk connections, with the National Theatre (NT) (as it was called before it got a ‘Royal’ appendage stuck at its front).

He brought this to bear when playing with Martin Carthy and John Kirkpatrick, Brass Monkey and the Home Service. Born in Chard, Somerset in England’s West Country on 29 February 1944, he died in North Cheam in Surrey on 17 March 2006. He first picked up a brass instrument (“baritone sax horn,” he told Owen Jones’ short-lived folk magazine Albion Sunrise, “it was actually a tenor sax horn”) when he was 10 and eventually graduated to cornet. At the age of 13 he passed an audition to play with the National Youth Brass Band. He left school aged 15. In 1961, after a couple of years of scratching a non-musical living, he responded to an advert in the UK magazine British Bandsman for experienced cornet players. The Welsh Guards recruited him on talent and because he father was Welsh. Nine years as a bandsman with the Welsh Guards followed and later drew on this experience with choice morsels such as Old Grenadier in Brass Monkey’s repertoire or the inclusion of Percy Grainger’s Lincolnshire Posy in the Home Service’s repertoire. They illuminated the British folk scene. He also did sessions for the likes of Leon Rosselson and Loudon Wainwright III. He just regarded himself as a musician, not a folk musician or any other musical subgenre.

Howard Evans could play anything brassy, whether trumpet, cornet, flugelhorn or, on one occasion in an NT production, alpenhorn. He was a total musician as happy analysing Miles Davis’ Sketches of Spain or Dave Brubeck’s ‘Take Five’ as a little Percy Grainger or something from The Who. He had managed to get a foot inside the NT pit in the 1970s with Tales From The Vienna Woods. Productions such as The Plough And The Stars and Sir Gawain & The Green Knight tumbled after, leading to the invitation to join Ashley Hutchings’ post-Rise Up Like The Sun Albion Band, then preparing for the Bill Bryden’s production of Lark Rise in the NT’s Cottesloe Theatre. The NT’s ‘Green Room’ was renowned for its conviviality. Out of one conversation came the offer for him to work with the guitarist and vocalist Martin Carthy and the free reed maestro and vocalist John Kirkpatrick. It seemed a good idea. The first fruits of their newly hatched partnership were him overdubbing trumpet on Jolly Tinker and Lovely Joan on Carthy’s Because It’s There (1979). By January 1980 they were out gigging as a three-piece which was when I first met him.

That trio grew and in January 1981 metamorphosed into a fresh elemental force eventually called Brass Monkey, an idiom open to various interpretations, as a quintet with Martin Brinsford playing sax, mouthorgan and percussion and Roger Williams trombone, occasionally tuba and euphonium. They stayed together, apart from a period in which Richard Cheetham occupied the trombone chair Williams rejoined. Their head-turning Brass Monkey (1983) (now combined with their second LP See How It Runs (1986) – derived from the Saxa Salt catchphrase – as The Complete Brass Monkey (1993)) contains a remarkable reworking of the incest ballad The Maid And The Palmer, one of the most daring and mesmerising performances ever committed to posterity or perdition. The combination of Evans, Williams and Brinsford playing together will be etched into anyone’s memory who saw them. They were that potent a force. Brass Monkey went on to make five albums with Sound & Rumour (1998), Going & Staying (2001) and Flame of Fire (2004). It was while touring with Brass Monkey that Evans fell ill. He was diagnosed as having cancer. We spoke afterwards and he confessed to an initial rush of ‘Why me?’ thoughts, soon eclipsed, typically, by a ‘Why not me?’ reflection.

That trio grew and in January 1981 metamorphosed into a fresh elemental force eventually called Brass Monkey, an idiom open to various interpretations, as a quintet with Martin Brinsford playing sax, mouthorgan and percussion and Roger Williams trombone, occasionally tuba and euphonium. They stayed together, apart from a period in which Richard Cheetham occupied the trombone chair Williams rejoined. Their head-turning Brass Monkey (1983) (now combined with their second LP See How It Runs (1986) – derived from the Saxa Salt catchphrase – as The Complete Brass Monkey (1993)) contains a remarkable reworking of the incest ballad The Maid And The Palmer, one of the most daring and mesmerising performances ever committed to posterity or perdition. The combination of Evans, Williams and Brinsford playing together will be etched into anyone’s memory who saw them. They were that potent a force. Brass Monkey went on to make five albums with Sound & Rumour (1998), Going & Staying (2001) and Flame of Fire (2004). It was while touring with Brass Monkey that Evans fell ill. He was diagnosed as having cancer. We spoke afterwards and he confessed to an initial rush of ‘Why me?’ thoughts, soon eclipsed, typically, by a ‘Why not me?’ reflection.

Working in the NT brought him into contact with an eleven-piece Albion Band offshoot rehearsed from November 1980 and March 1981 near the NT while working on The Passion. The tentatively titled First Eleven chrysalis included Evans and Kirkpatrick. The group that finally emerged, a mere septet, was the Home Service, England’s most forceful electrified folk group Fairport Convention and Steeleye Span. They created a never-before-heard sound live. Even if their debut Home Service (1984) failed to deliver the band’s power and majesty, it revealed the power of their songwriting and arranging. The Mysteries (1985) with Linda Thompson as guest vocalist was a marked improvement but still tied them to their NT sinecure. They broke free with their masterful Alright Jack (1986). Evans shaped the work mightily, suggesting Percy Grainger’s Lincolnshire Posy, a suite he had encountered with the Welsh Guards. In the mixing room a copy of John Bird’s biography of Grainger was a fixture, a touch I loved.

At the 1982 Cambridge Folk Festival, whilst sitting with the writers Richard Hoare and the John Platt, that West Coast man of many strings David Lindley first heard an act billed as the Martin Carthy Band. A couple of years later, he told me, “It was the most exciting, original thing I’d heard in ten years.” Their proper name was Brass Monkey. Nobody had ever combined voice, stringed and free reed instruments, percussion, reed and brass instruments like Brass Monkey before. Maybe nobody had ever imagined that combination in its blending of folk and wind bands. At Jackson Browne and David Lindley’s Theatre Royal concert in London on 27 March 2006, Lindley called Brass Monkey “one of my favourite bands of all time” and dedicated El Rayo-X to Howard Evans saying “This song is supposed to have horns in it. He’ll be playing.”

At the 1982 Cambridge Folk Festival, whilst sitting with the writers Richard Hoare and the John Platt, that West Coast man of many strings David Lindley first heard an act billed as the Martin Carthy Band. A couple of years later, he told me, “It was the most exciting, original thing I’d heard in ten years.” Their proper name was Brass Monkey. Nobody had ever combined voice, stringed and free reed instruments, percussion, reed and brass instruments like Brass Monkey before. Maybe nobody had ever imagined that combination in its blending of folk and wind bands. At Jackson Browne and David Lindley’s Theatre Royal concert in London on 27 March 2006, Lindley called Brass Monkey “one of my favourite bands of all time” and dedicated El Rayo-X to Howard Evans saying “This song is supposed to have horns in it. He’ll be playing.”

At Howard Evans’ packed ‘leaving do’, the remaining four Monkeys played him out with Old Grenadier, one of pieces he had brought to the band’s table at the beginning.

Very much in Howard Evans’ memory, Brass Monkey continues to perform. Paul Archibald, on trumpets, piccolo trumpet and cornets, debuted live in March 2009 at the Electric Theatre in Guildford, Surrey playing a repertoire that included material from Brass Monkey’s then-unreleased Head of Steam (2009).

The Home Service album sleeve image is © and courtesy of Fledg’ling Records. The album sleeves and images of Brass Monkey are © and courtesy of Topic Records. In the first photo by John Haxby they are L-R: Martin Brinsford, Martin Carthy (below), John Kirkpatrick (above), Roger Williams and Howard Evans. In the second they are Martin Carthy, Howards Evans, Martin Brinsford, John Kirkpatrick and Richard Cheetham.

14. 3. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Life is rarely dull on the treasured island. More travellers’ tales, aka GDDs, from the faraway island – about love and deception, wading birds, coming on and vamoosing, work, tall trees in Kashmir, church bells and science fiction-inspired escapes. Bert Jansch, Lo Cor De La Plana, Carolina Chocolate Drops/Luminescent Orchestrii, Paul Kantner, Drewo, Gayathri Rajapur, Fairport and Shivkumar Sharma supply the music this month. By the way, the tally is not a miscount. Bert Jansch supplies two tracks.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Life is rarely dull on the treasured island. More travellers’ tales, aka GDDs, from the faraway island – about love and deception, wading birds, coming on and vamoosing, work, tall trees in Kashmir, church bells and science fiction-inspired escapes. Bert Jansch, Lo Cor De La Plana, Carolina Chocolate Drops/Luminescent Orchestrii, Paul Kantner, Drewo, Gayathri Rajapur, Fairport and Shivkumar Sharma supply the music this month. By the way, the tally is not a miscount. Bert Jansch supplies two tracks.

Jack Orion – Bert Jansch

Jack Orion – Bert Jansch

The LP jacket for Jack Orion, Bert Jansch’s third solo album for Transatlantic, had a simple elegance. The front cover had a shadowy portrait of Jansch playing his acoustic guitar taken by Brian Shuel, the folk photographer of the period. In 1966 the norm was for UK record sleeves to be laminated. Instead of the beetle-back sheen that lamination brought, Jack Orion‘s finish was matt black. Like a blackboard. On the rear of the sleeve there was a reversed out, white out of black image of the eponymous hero-fiddler of the title song.

On went the album and for the first time Bert Jansch made total sense. The first two albums – Bert Jansch and It Don’t Bother Me had been very good in parts but this time the album worked as a coherent whole. Jack Orion is a tale of seduction and deception and Jansch and John Renbourn’s guitars combine magically to propel it along. Jack Orion is a fiddler who can fiddle fish from salt water. He is also a bit of a charmer. The lady of high renown certainly falls for him and asks him to visit her at daybreak. Naturally, he needs to build up his strength with a little rest and is ably assisted in this by his servant Tom who sings and fiddles him to sleep, promising to wake him in time for his tryst. Tom then pops along to the countess while his master sleeps. Things start unravelling when the lady asks Jack Orion if he is returning to taste more of her love. Well, you’d be confused, too. Gripping stuff then and gripping stuff still. From Jack Orion (Castle Music CMRCD304, 2001)

Hit ‘Em Up Style – Carolina Chocolate Drops/Luminescent Orchestrii

According to the press release, at the Folk Alliance bash in Memphis, Tennessee, Sxip Shirey of the New York-based Romanian punk Gypsy band, the Luminescent Orchestrii spotted the Carolina Chocolate Drops’ Rhiannon Giddens clocking them and called her over. This is the more permanent upshot of the invitation. What a combination for this line-up of the Drops to go out on a parting gift! There is a wide-cast wit and a humour to this performance. Plus any recording that goes out on almost an Earl Okin-style mouth trumpet flourish is deserving of your ear time. Such a shame it’s only an EP. A version of the song appeared on the Drops’ Genuine Negro Jig (2010). From Carolina Chocolate Drops/Luminescent Orchestrii (Nonesuch 7559 79779-9, 2011)

Have You Seen The Stars Tonite – Paul Kantner/Jefferson Starship

Have You Seen The Stars Tonite – Paul Kantner/Jefferson Starship

Have You Seen The Stars Tonite is full-throttle science fiction set to the San Francisco Sound of 1970. The performance is fantabulous, one of those budget-no-option, let’s-roll-tape parties that bottled a fragrance of the Bay Area music scene for posterity. David Crosby (who gets the compositional co-credit with Paul Kantner), Jerry Garcia and Mickey Hart throw in musical shapes to enhance and nudge on Paul Kantner and Grace Slick’s vision.

What got me on its vinyl release was its sound and that still remains. The piano is especially important in the mix. It should have been Nicky Hopkins: it sure sounds like him. It is Grace Slick. And her playing still sends me. Have You Seen The Stars Tonite – still no question mark – is a mini-SF saga all on its own. Pun intended. From the expanded Blows Against The Empire (RCA/Legacy 82876 67974 2, 2005)

Oj zajdy, zajdy ty misiacu na tu poru – Drewo

It wasn’t the best interview I’ve ever done. Petr Dorůžka and I did it as a double-hander. We were both mesmerised by this wonderful, traditional Ukrainian polyphony that had come to TFF Rudolstadt. It was village music with extraordinary potency with wonderful upsweeps at the end of a line – much in, say, the Bulgarian style from the Pirin Mountains. But when experiencing it in the flesh it was its own thing and it sounded heady. Their unaccompanied singing was transfixing. Petr and I met several of the Drewo ladies for an interview. It soon became apparent that no matter which language their profundities about Ukrainian folksong were going to be translated into, all the nuances were going to be lost in a sea of blandness. In that Slav language pivot sort of way that Czech can be, Petr began offering suggestions for translating Ukrainian words.

This song, the CD booklet notes explain, translates as ‘Oh moon hide your light’. Its tiered vocals are high-ringing. At times, they have the fluency of the Watersons – a comparison not lightly given – in the ways the voices interlock and interweave. Even though the Drewo was slightly short of this album’s line-up, recorded at Hendrix Studio, Lublin in Poland in July 2001, the ensemble still flew. Mariana Sadovska, a major facilitator of this recording, be praised. From Budemo wesnu spiwaty/Song Tree (SEiAK 001, 2003)

Kruti: Hatna Raga – Gayathri Rajapur

Kruti: Hatna Raga – Gayathri Rajapur

The gottuvadyam is a South Indian vina – in this context, a vina of stick zither-style construction (rather than the generic word for ‘stringed instrument’) – played with a slide. At the time of this recording’s release in 1967 it was indomitably obscure and, as with many Folkways releases, I have no recollection of encountering it in either Collet’s or Dobell’s – the two London record shops that might just have occasionally stocked it. Besides, Folkways albums came at a premium price beyond my pocket.