Articles

[by Ken Hunt, London] Planning a trip to England, Scotland and/or Wales? Hoping your visit coincides with some musical adventures? The highly recommended Spiral Earth guide is the ideal place to start planning your time and trip.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Planning a trip to England, Scotland and/or Wales? Hoping your visit coincides with some musical adventures? The highly recommended Spiral Earth guide is the ideal place to start planning your time and trip.

In addition to major fixtures such as Cropredy, Whitby Folk Week, Towersey and Glastonbury, expect to uncover the unexpected – such as the Pipe and Tabor Weekend, Morpeth Northumbrian Gathering and the Sunrise Celebration.

The guide details UK folk, roots and alternative festivals by month and geography with a map to click on. The map won’t allow you to click on, say, the Channel Islands for the Sark Folk Festival and the map doesn’t include Northern Ireland but using the January-April, May, June, July, August and September-December options will get you places by another route. You get the festival’s name, the dates and the website.

Plus it has a breaking news section.

www.spiralearth.co.uk/festivals/default.asp

The images of Fairport’s Cropredy Convention 2008 are © Santosh Sidhu/Swing 51 Archives.

20. 2. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] East German rock music, nowadays known as Ost-Rock (Ost means east), has never had a champion outside the old East. Sure, Julian Cope got wiggy and witty with Krautrock in all its Can, Kraftwerk and Ohr-ishness. But aside from, say, coverage in the Hamburg-based magazine Sounds in the 1980s and Tamara Danz (1952-1996) – and Silly’s lead singer’s fleeting appearance in the last edition of Donald Clarke’s Penguin Encyclopedia of Popular Music – Ost-Rock got short shrift outside its place of origin, the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Götz Hintze’s Rocklexikon der DDR (2000) and Alexander Osang’s Tamara Danz (1997) biography have redressed the balance somewhat. But Hintze and Osang wrote accounts in German. Probably, no English-language champion will take up Ost-Rock‘s colours now.

[by Ken Hunt, London] East German rock music, nowadays known as Ost-Rock (Ost means east), has never had a champion outside the old East. Sure, Julian Cope got wiggy and witty with Krautrock in all its Can, Kraftwerk and Ohr-ishness. But aside from, say, coverage in the Hamburg-based magazine Sounds in the 1980s and Tamara Danz (1952-1996) – and Silly’s lead singer’s fleeting appearance in the last edition of Donald Clarke’s Penguin Encyclopedia of Popular Music – Ost-Rock got short shrift outside its place of origin, the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Götz Hintze’s Rocklexikon der DDR (2000) and Alexander Osang’s Tamara Danz (1997) biography have redressed the balance somewhat. But Hintze and Osang wrote accounts in German. Probably, no English-language champion will take up Ost-Rock‘s colours now.

Silly were part of a forward-thinking movement, as this 8-CD set shows. The choice of name was a gesture of defiance. German, like every language in my experience, has a plethora of variables orbiting every society’s central and intrinsic idea of stupidity. However, the English word silly captures a special nuance of meaning that kindred German words such as doof, bescheuert or bekloppt do not. Plus, back when, it had the sexiness of an import word in a forbidden language. Russian was the GDR’s second language.

Die 7 Original-Alben – you don’t need a translation – has Silly’s seven Amiga – the only game in town – albums at its heart. You get Tanz Keiner Boogie? (Can’t anyone boogie? or Can’t anyone do the boogie?, 1981), Mont Klamott (the colloquial name of a pimple of a hill, the Grosse Bunkerberg in the Volkspark Friedrichshain in the Berlin district of Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, 1983), Liebeswalzer (Waltz of Love, 1985), Bataillon D’Amour (Love Crowd, 1986), Februar (February, 1989), Hurensöhne (Sons of Whores, 1993) and Paradies (Paradise, 1996) with a judicious scattering of bonus tracks. The set is rounded off with a documentary CD with their vocalist Danz talking about the band.

Somebody obviously tried to make and market Danz as the GDR’s version of Tina Turner with a side-order of Elkie Brooks. Sure, on the surface Tamara had big hair (like Kim Wilde), wore leopard-skin-print pants (like Kim Wilde), and was the whip-crack-away mistress of sublime naughtiness and raunchy sophistication (quite unlike Doris Day). But she was one of the world’s greatest rock vocalists as well. She rocked and Silly rocked, too. Silly’s story is a tale of malcontent music pushing the boundaries, absorbing foreign inspirations (Abendstunden – ‘Evening hours’ – on Mont Klamott album has a certain Vienna vibe, kinda via Ultravox). Silly were at the forefront of the blossoming of something beyond state-tolerated, state-controlled, youth energy-channelling beat music.

One time Scarlett O’ (Seeboldt) – the former female lead singer of Wacholder, then branching out into new musical pastures – and I drove through Berlin. Scarlett is both an education and, as the English idiom goes, a caution. Like we always do, we jawed at length and in detail about how it had been making music in the old GDR. We talked a great deal about Tamara Danz, including her death from cancer. To say that Scarlett O”s respect for Danz was enormous would be an understatement.

Probably, gentle reader, you never heard Silly. I do hope someday you will.

Silly: Die 7 Original-Alben (Sony/BMG Amiga 82876823232, 2006)

14. 2. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] More travellers’ tales, aka GDDs, from the faraway island – this time from Bryan MacLean, June Tabor, The Everly Brothers, June Tabor, The United States of America, Eddie Reader, The McPeake Family, Clara Rockmore, Shujaat Khan, Artie Shaw and Christy Moore with Declan Sinnott. The strangest thing happened this month. Just like the S.S. Politician going down off Eriskay in the Outer Hebrides in 1941 and the 1949 Ealing comedy Whisky Galore, all these bottles of single malt whisky washed ashore in time for Burns’ Night. Nobody was more surprised than me…

Old Man – Bryan MacLean

Bryan MacLean’s songs were one of the multifarious delights that made up Love’s Forever Changes, one of the great visionary albums of 1967. It is a work that I have never stopped revisiting. MacLean’s solo version of the song was recorded the year before. There is so much air in his version and not only because it is just voice and acoustic guitar or because it lacks the orchestrations of Love’s take on the song. MacLean (1946-1998) was not a hugely prolific songwriter, it seemed at the time. But what emerged was quality.

A post-Love solo contract with Elektra Records fell through, though he carried on writing and went on to produce a whole canon of Christian devotional songs; apparently only one recording project was of studio quality and this was issued posthumously. The ifyoubelievein anthology of music recorded between 1966 and 1982 has notes from MacLean himself and David Fricke. From ifyoubelievein (Sundazed SC 11051, 1997) More at http://www.bryanmaclean.us/

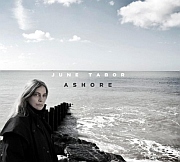

Finisterre – June Tabor

Finisterre – June Tabor

This sea-themed programme, then lacking its final title, debuted as part of the seventieth anniversary celebrations of Topic Records at the Queen Elizabeth Hall (QEH) on 18 September 2009. It was clearly going to undergo change. For a start, its suite of songs and recitations was too long for a single CD. Ian Telfer’s Finisterre is one of the pieces that survived the transitions and repertoire re-balancings. On Ashore, as at the concert, June Tabor is joined by Andy Cutting on diatonic accordion, Mark Emerson on violin and viola, Tim Harries on double-bass and Huw Warren on piano.

She first recorded Finisterre on her and the Oyster Band’s jointly billed Freedom and Rain (1990). It was the valedictory piece at the QEH concert. It is now ‘promoted’ to both the suite’s opener and song and performance. It’s strong enough to merit its new position. Its slow rolling arrangement conjuring the rise and fall of waves in motion sets the suite up marvellously. The strength of her rendition says everything about why she is one of the finest song interpreters ever to have emerged from England’s Folk Revival.

PS Quite why the men from the ministry scuppered Finisterre and replaced it with FitzRoy in 2002 baffles me. Finisterre has a Land’s End mystery to it. To rename it with something that looks like a literal (typo for our US readers) or a character from a ropey novel by Walter Scott is bureaucratic folly. It does now mean that the song’s opening declaration “Farewell Finisterre…” has an added poignancy. From Ashore (Topic TSCD577, 2011)

More information at www.topicrecords.co.uk

I Wonder If I Care As Much – The Everly Brothers

The first time popular music became mine made and made any real sense to me was when I heard my older cousins’ Everly Brothers singles. Hitherto pop music was all Doris Day, Max Bygraves, Sputniks or Bachelors patterned wallpaper. A great deal to do with clicking with the Everlys was the way Don and Phil Everly’s voices blended and interwove. Roots is my all-time favourite album of theirs. Lenny Waronker’s production brought out something which I hadn’t heard in their earlier material like Wake Up Little Susie, All I Have To Do Is Dream or Bye Bye Love.

This song, credited to Don Everly, is the only original on the album. It sits beside material from, amongst others, Glen Campbell, Merle Haggard, Ron Elliott and Randy Newman. The piece starts with an attention-grabbing whooshing electric guitar over a simple but effective rhythm line on electric bass. There were no musician credits on the original LP in 1968 or on the undated Warner Archives CD reissue; it could possibly be Ron Elliott of the Beau Brummels on electric guitar. The song lasts for less than three minutes but they cram a lot into its elegant minimalist arrangement. From Roots (Warner Brothers 7599 26927-2, undated CD reissue)

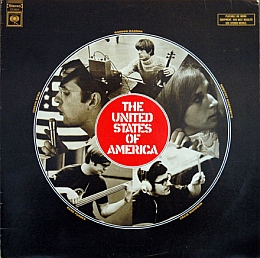

Love Song For The Dead Ché – The United States of America

Love Song For The Dead Ché – The United States of America

Reading Pat Long’s mention of The United States of America in the Guardian‘s obituary of Broadcast’s Trish Keenan prompted this Giant Donut Disc. The United States of America were Joseph Byrd on electronic gizmos, electric harpsichord, organ, calliope and piano, lead vocalist Dorothy Moskowitz, Gordon Marron on electric violin and ring modulator, Rand Forbes on electric bass and Craig Woodson on electric drums and percussion. In 1968 the music they made was unlike anything I had heard.

Love Song For The Dead Ché is under three-and-a-half minutes in length. In mood and style it contrasted with the album’s other material like their cheeky sound-collage The American Way of Love, harder driving material like The Garden of Earthly Delights or the social satire of I Won’t Leave My Wooden Wife For You, Sugar. Love Song For The Dead Ché is quieter, more meditative. At the time there was only one Ché in the news but this song’s wistfulness maintains an ambiguity.

Love Song For The Dead Ché is under three-and-a-half minutes in length. In mood and style it contrasted with the album’s other material like their cheeky sound-collage The American Way of Love, harder driving material like The Garden of Earthly Delights or the social satire of I Won’t Leave My Wooden Wife For You, Sugar. Love Song For The Dead Ché is quieter, more meditative. At the time there was only one Ché in the news but this song’s wistfulness maintains an ambiguity.

Moskowitz, it struck me, was unfairly underrated in an underrated band best-known in western Europe for I Won’t Leave My Wooden Wife For You, Sugar’s appearance on CBS’ seemingly ubiquitous, budget-priced sampler The Rock Machine Turns You On, released in Britain and the Netherlands (at least) in 1968. Sundazed’s expanded edition of the original album reinforces how innovative the band was. It also includes hitherto unreleased material. For example, the gagaku-inspired Osamu’s Birthday and the Columbia audition recording of The Garden of Earthly Delights. The Sundazed edition has notes by Joseph Byrd and includes an interview with Dorothy Moskowitz. Still, the gentle threnody of Love Song For The Dead Ché is the one I plumped for.

After the United States of America, Moskowitz worked with Joe McDonald on his Paris Sessions. Much, much later I discovered in my exploration of the gottuvadyam or chitra vina that she had played tanpura (string drone) on Gayathri Rajapur’s Ragas from South India (Folkways FW 8854, 1967). There is always so much more to learn. From The United States of America (Sundazed 11114, 2004)

Perfect and Ae Fond Kiss – Eddie Reader

As I dip the quill into the container of octopus ink, it is Burns Night 2011 – 25 January 2011. Tonight, when I have finished the day’s writing, I shall raise a dram in memory of Robert Burns (1759-1796). It has been a custom every Burns Night to savour his words and to reflect on the blessings of friendship, love and loss. I generally conjoin Burns and a line from Hilaire Belloc in that finest of causes. His aphoristic line rings down the years: “There’s nothing worth the wear of winning, but laughter and the love of friends.” For many years I believed it was a line of Burns’ in fact.

Of all the many recorded interpretations of Burns’ material that I have listened to, none has given me greater pleasure or cause to imbibe his poetry than Eddie Reader Sings The Songs The Songs of Robert Burns (2003). However, tonight, with the spirit of Burns loitering and accosting, something less studio, something looser and a little more rowdy is called for. This one fit the bill. Eddi Reader sings and plays guitar, Boo Hewerdine dittos, Graham Henderson is on things squeezed, blown and strummed and sings, Christine Hanson is on cello and vocals, Colin Reid is on guitar and John McCusker plays fiddle and whistle on this live album.

This performance captures the exuberance of Reader’s old Fairground Attraction hit, contrasted with Burns’ hymn to unrequited love. Her introduction to Perfect, placing it in a Glasgow setting, is lovely. After she’s sung it she goes into a spoken introduction for Ae Fond Kiss (Scots for One Fond Kiss). It is literary history told in an amusing way and it grants an impossible new stratum of meaning to the word unrequited. The object of Burns’ unconsummated longings warded off his pleas for a naughty though by way of compensation Burns did manage to get her maid doubly with child. Twins were in the poet’s genes. The great joy with these two songs is Reader’s acrobatic voice. Oh what a voice! On Burns Night it’s within the spirit of the rules to cheat and pick two performances. From Live: London, UK 05.06.03 (Kufala KUF 0039, 2003)

McLeod’s Reel – The McPeake Family

This was first released in 1963. The great Bill Leader recorded this album the previous year. For me, it bottles the essence of home-made music, music made when a family is sitting around and ‘having a play’. The tune may now be familiar as hell but Bill captured something rough, ready and, most importantly, perfect with this performance. From Wild Mountain Thyme (Topic Records TSCD583, 2009)

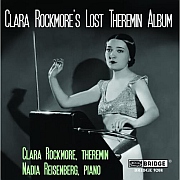

Kaddish – Clara Rockmore

Kaddish – Clara Rockmore

Lev Sergeyevich Termen, better known as Leon Theremin in the West, has a fascinatingly complex story I shall leave to others to tell. The instrument named after him that he bequeathed the world is as simple as its voice is rich. If he ever had a finer acolyte than Clara Rockmore (1911-98) to carry forward his musical message, please disabuse me. During the early 1990s, there was talk and budget to work on a project with her. I volunteered to write the notes on the spot. It never happened, unfortunately. This recording with Nadia Reisenberg on piano is of a piece by Ravel. It reveals a wondrous command of slow-tempo theremin. Plus the piano is like a light shower of raindrops through which the theremin shines. She bent soundwaves so deliciously. From Clara Rockmore’s Lost Theremin Album (Bridge 9208, 2006)

You can watch a rare video of Ravel’s Habanera with Clara Rockmore and Nadia Reisenberg here: www.youtube.com

Bilaskhani Todi – Shujaat Khan

This is a sprawling canvas of a performance, a full-scale depiction of Bilas Khan’s variant of the morning raga Todi. Shujaat Khan’s brushwork teems with detail. Bilas Khan, to whom this piece is attributed (hence the name), was the son of the myth-draped master musician Miyan Tansen of the court of the Mughal emperor Akbar (ruled 1556 to 1605). Bilas Khan had certain difficulties when succeeding his father. He won the position of successor to his father’s musical lineage through the simple expedient of playing music so poignant that his father’s corpse moved. Or so the legend goes. Shujaat Khan also had a hard act to follow. His father, with whom he sometimes had a fraught relationship, was the sitar maestro Vilayat Khan. An unenviable task for a sitarist. Let’s not go down the leafy lane to the Land of Comparative Cod Psychology, however.

This performance, assisted by Samir Chatterjee on tabla, lasts over an hour. It is definitely a canvas to return to periodically. Mainly because it is one that you know you haven’t taken in completely and viewing it from a different perspective in time always pays dividends. It was recorded in June 1995 in New York City with Lyle Wachovsky producing. It is one of my absolute favourite Shujaat Khan interpretations. From Shujaat Khan – Sitar (India Archive Music IAM CD 1046, 2001)

Concerto For Clarinet – Artie Shaw

Recorded in December 1940, this is one of the five to ten pieces of music that I have listened to the most in my life. I grew up with it. Its presence dominated my childhood as no other piece of music did. We had it on a 78 rpm single and I played it on the wind-up gramophone over and over. Johnny Guarnieri’s boogie-woogie piano and Nick Fatool’s drumming were buzzes. But best of all was Artie Shaw’s high-soaring clarinet. Clarinet was a constant in my childhood and youth because my father played clarinet and alto. Before going out to gig he would warm up in front of the mirror. He would routine some current hit from the radio or sight-read something from the pile of sheet music on alto sax and clarinet. He’d adjust the reeds, perhaps shave a sliver off the Selmer reed and when he was satisfied with his embouchure and the reeds, he would turn to Concerto For Clarinet. At some stage he had transposed it for his instrument but he never bothered with the sheet music. He would play the clarinet solo from the last minute and ten seconds of the record. Artie Shaw scales the heights with some serious harmonics by the end, all of which my father negotiated adroitly. All and all, a very reinforcing experience for a young mind.

When my friend Bernhard Hanneken was compiling the outstanding collection of single-reed instrument music from which this comes – an anthology going from A.K.C. Natarajan and Naftule Brandwein to Benny Goodman (since you ask, Verbunkos from Bartók’s Contrasts) and Eugène Delouch – Artie Shaw’s name came up. I was enough of a zealot to have Shaw’s autobiography, The Trouble With Cinderella – An Outline of Identity (1955) and with a headful of childhood memories, which other piece was I going to argue for? It was a foregone conclusion. Bernhard’s anthology is simply amazing, a work of extraordinary disquisition groaning like a treasure galleon with unexpected riches. From Magic Clarinet – The Single-Reed Instruments I, Disc 2 (NoEthno 1005/6/7, 2010)

More information at www.noethno.de

No Time For Love

No Time For Love – Christy Moore with Declan Sinnott

– Christy Moore with Declan Sinnott

Just to prove that it is possible to adapt to modern times this version of Jack Warshaw’s song is from one of those new filmmabobs. Roy Bailey brought the song to a wider audience on his 1982 album Hard Times on Fuse. However, No Time For Love entered my life that same year with its appearance on Moving Hearts’ self-titled debut album.

It’s not a tidy song. It is a jumble of ideas. Some of the ideas work. Some lines don’t sing well and could ‘wrong-throat’ a singer. Sometimes the lyrics change, as here. “The sound of the siren’s the cry of the morning.” is a fine rock’n’roll exit line for this energy-filled song. With sirens going off in Cairo’s Tahrir Square as I write, it is very much a time for love.

The song suited Moving Hearts – which both Christy Moore and Declan Sinnott were members of – on many levels. But what sends this particular rendition into a different space is Declan Sinnott. His electric guitar playing is nimble, sinuous and altogether splendid. He soars away, leaving Christy Moore to perspire and thrash and bash the living bejesus out of the old acoustic. From the DVD Come All You Dreamers – Live at Barrowland, Glasgow (no number, 2009)

For more about the lads go to www.christymoore.com

There is also an interesting piece on the Dublin-based graphic design studio Swollen’s website concerning the spec and design of the DVD’s packaging at www.swollen.ie/index.php?/christy-moore-live-at-barrowland/

The image of Declan Sinnott (left) and Christy Moore is © Santosh Sidhu/Swing 51 Archives. The copyright of all other images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers.

6. 2. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Bengali singer Suchitra Mitra died on 3 January 2011 at her home of many years, Swastik on Gariahat Road in Ballygunge, Kolkata. She was famed as one of the heavyweight interpreters of the defining Bengali-language song genre form called Rabindra sangeet – or Rabindrasangeet (much like the name Ravi Shankar can also be rendered Ravishankar). ‘Rabindra song’ is an eloquent, literary, light classical song form, derived from the name of the man who ‘invented’ it, Rabindranath Tagore, the winner of the 1913 Nobel Prize for Literature.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Bengali singer Suchitra Mitra died on 3 January 2011 at her home of many years, Swastik on Gariahat Road in Ballygunge, Kolkata. She was famed as one of the heavyweight interpreters of the defining Bengali-language song genre form called Rabindra sangeet – or Rabindrasangeet (much like the name Ravi Shankar can also be rendered Ravishankar). ‘Rabindra song’ is an eloquent, literary, light classical song form, derived from the name of the man who ‘invented’ it, Rabindranath Tagore, the winner of the 1913 Nobel Prize for Literature.

Tagore’s songs helped define Bengali and Bangladeshi culture and identity – and importantly pan-Indian culture – in the years before the dissolution of the British Raj and afterwards. He died in 1941 and it was a cause of immense regret that she began her studies at Tagore’s Santiniketan – meaning ‘abode of peace’ – days after his death without having met him. However, she did study with some of the illustrious, next-generation exponents of the form in situ.

Although Suchitra Mitra will be remembered as one of the greatest ever interpreters of the Rabindra sangeet song form, she was massively important for her championing of Tagore as a cultural icon – for once the cliché ‘cultural icon’ is justified. She danced in Rabindra Nritya Natyas – his dance dramas -, taught and wrote about him and his works. She became one of the great authorities on him and his art.

She was born in what was then known as Central India Agency in British India on 19 September 1924. At the time her mother was on a train and for some reason was too preoccupied to note where exactly.

Regrettably the photo copyright information and the photographer’s name are unknown. We will correct this and/or remove the image when known.

31. 1. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Bengal’s popular arts lost two of its major figures on 17 January 2011.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Bengal’s popular arts lost two of its major figures on 17 January 2011.

The actress Gita Dey (1931-2011) died in north Kolkata. From her debut as a child actor in 1937 in director Dhiren Ganguly’s film Ahutee, she reportedly appeared in some 200 Bengali films and thousands of stage dramas and folk plays. A startling character actress with a presence that did not overwhelm the part, she appeared in such films as film director Ritwik Ghatak’s Meghe Dhaka Tara (1957), Satyajit Ray’s Teen Kanya and Komal Gandhar, and Tapan Sinha’s Haatey Baajarey, Jotugriha and Ekhonee. Lawrence Olivier was amongst the people who celebrated her.

The singer Pintu Bhattacharya’s death some five hours later at the Thakurpukur Hospital in south Kolkata was slightly overshadowed by that of his contemporary. He was an exponent of popular Bengali modern song (as it is known) and worked with many of the Bengali film industry’s foremost music directors including Salil Chowdhury (1922-1995) and for a range of film directors, including Tapan Sinha. Although he was something of a household name in Bengal, he was little known outside the region – a great shame for someone blessed with such a wondrous voice and interpretative skills. A big fish in a small pond, he was later sidelined by the Tollygunge film industry.

24. 1. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] One of my fondest memories of Britain’s specialised music magazine scene of the 1980s into the 1990s is how little ego and rivalry there was for the most part. There were a couple of exceptions (no names, no pack drill) and, strange though it may seem, not a single ornery person from that bunch stayed the course within music criticism. Keith Summers wrote about music, collected it (as in, made field recordings of such as Jumbo Brightwell, the Lings of Blaxhall, Cyril Poacher and Percy Webb as well as later contributing to Topic’s multi-volume series Voice of the People) and published magazines about it. He had the fall-back trade of accountant that funded his passions.

[by Ken Hunt, London] One of my fondest memories of Britain’s specialised music magazine scene of the 1980s into the 1990s is how little ego and rivalry there was for the most part. There were a couple of exceptions (no names, no pack drill) and, strange though it may seem, not a single ornery person from that bunch stayed the course within music criticism. Keith Summers wrote about music, collected it (as in, made field recordings of such as Jumbo Brightwell, the Lings of Blaxhall, Cyril Poacher and Percy Webb as well as later contributing to Topic’s multi-volume series Voice of the People) and published magazines about it. He had the fall-back trade of accountant that funded his passions.

In 1983 Summers launched an excellent magazine called Musical Traditions. A number of us already knew him from concerts or shindigs but issue one gave an idea of how he meant to continue and of his wider tastes with pieces on the Nigerian juju musician I.K. Dairo, the Irish piper, storyteller and folklorist Séamus Ennis, East Anglia’s wondrous traditional singer Walter Pardon and the Armenian musician Reuben Sarkasian. Many of the magazines that we published were basically one-man shows. Few lasted too long. The attrition rate due to bad debts, lost consignments and volunteer labour stretched too far did for many of us. Musical Traditions lasted for twelve physical issues. Yet, as if putting out one magazine wasn’t enough, Summers started up Keskidee, devoted to black music traditions. It managed three issues.

Summers was drawn to the Irish folk tradition. He recorded extensively between 1977 and 1983 in Co. Fermanagh in Northern Ireland. It culminated in his two-CD set, The Hardy Sons of Dan (Musical Traditions MTCD329-0, 2004), subtitled “Football, Hunting and Other Traditional Songs from around Lough Erne’s Shore”, with a collection of performances by the likes of James and Paddy Halpin, Packie McKeaney and Maggie Murphy.

One underreported aspect of dear old Keith was his own idiosyncratic singing. I remember it rather fondly. Like yesterday in fact. It was rather as if he had just staggered out of an Essex or Sarf London pub after a Sunday lunchtime session on the way to the figuratve seafood stall. (Back in those dark Sundays pubs were open for a measly two hours and then closed until the evening.) By way of background to the following anecdote, Keith and I had been to an exceedingly fine concert as part of the Crossing the Border festival the previous night. Lyle Lovett had sung his then unreleased I Married Her Just Because She Looks Like You (later to appear on Lyle Lovett And His Large Band (1989)). On the way out, full of Lebensfreude, we gazed into each other’s eyes and, without cue, Summers and Hunt broke into song – well, more the chorus which was pretty much the song’s title.

The next afternoon Keith and I found ourselves at the same press bash in the capital – the act, occasion and purpose banished and blotted out by the event’s free alcohol and the passing years. It having nothing to do with Lyle Lovett is all I remember. We did our damnest to help the cullet mountain by drinking uncounted bottles of foreign lager of export strength. Having done our bit for recycling and, importantly, having made sure there was no more to be had, we strolled down Tottenham Court Road in the sunshine hammily singing Lyle’s fine new song as an alcohol-acoustic loop all the way to Collet’s folk emporium at the top of Charing Cross Road where we treated the folk department’s manager, Gill Cook to several rousing loops of the same. She took it in good spirits, sat us down, made us tea and we talked. Cunning sangsters that we were, we kept the conversation flowing until about ten minutes before pub opening time. This coincided with the shop shutting, when the three of us swanned down to the nearby Angel at St. Giles High Street for liquid refreshments. Let’s not beat about the bush, damn it, that sunny afternoon Keith and I were Lyle Lovett’s right-hand men. He was Essex Lyle. I was Sarf London Lyle.

Born on a London double-decker bus outside Hackney General Hospital in, Hackney, East London on 11 December 1948, Keith Summers died at Southend-on-Sea, Essex on 30 March 2004.

There is a wonderful account of The Hardy Sons of Dan at www.mustrad.org.uk/articles/hardyson.htm

Ken Hunt’s obituary of Keith Summers is at www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/keith-summers-549731.html

16. 1. 2011 |

read more...

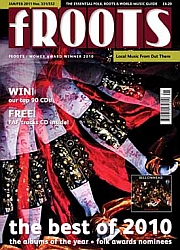

[by Ken Hunt, London] Winter draws on in London but on the fictitious tropical island the sun is shining. Helping to banish gloom this month is a rather fine selection of music. Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, this month’s haul of traveller’s tales embraces Martin Simpson, Ella Ward, Yardbirds, Shashank, Don Van Vliet, David Lindley & El Rayo-X, Rickie Lee Jones, Swamy Haridhos & Party, Cyril Tawney and Anne Briggs.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Winter draws on in London but on the fictitious tropical island the sun is shining. Helping to banish gloom this month is a rather fine selection of music. Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, this month’s haul of traveller’s tales embraces Martin Simpson, Ella Ward, Yardbirds, Shashank, Don Van Vliet, David Lindley & El Rayo-X, Rickie Lee Jones, Swamy Haridhos & Party, Cyril Tawney and Anne Briggs.

The Swastika Song – Martin Simpson

The Swastika Song – Martin Simpson

I never lived through a European war. Many people I loved and love did. I only knew the survivors. I have lived and worked with people of many nationalities who did survive wars. Some were fascist. Some were unrepentant and boasted. I’ve also lived with, and spoken to people who have lived under totalitarian regimes, sometimes more than once in their lives. I have heard tales from survivors and survivors’ children that will haunt me to my grey cells run dry. Martin Simpson’s song brings it all back home and to mind. “Don’t say it can’t happen/Say it can’t happen here.” A potent song. From FAF Tracks (while available, exclusively with fRoots issue 331/332, January/February 2011)

www.frootsmag.com

On The Banks of Red Roses – Ella Ward

Jean Ritchie and her husband George Pickow made this recording of Ella Ward, “a pretty young Edinburgh housewife and mother of two children” on a research jag funded by a Fulbright scholarship that sent them the Britain and Eire in late 1952. According to Ritchie’s booklet notes to the CD reissue, Ella Ward had learned the song from the School of Scottish Studies folklorist Hamish Henderson. It’s a song about woman’s love betrayed. Unto death. Ella Ward’s singing captures the narrative beautifully from being easily led astray to blind devotion, culminating in being stabbed to death and tumbled into a prepared grave. Oh, the power of traditional song! From Field Trip (Greenhays GR726, 2001)

Hamsadhwani – Shashank

Hamsadhwani – Shashank

Hamsadhwani is a South Indian ragâm of great portability. In Shashank’s hands it flies. It is a ragām grounded in the natural world. Nature is, after all, a principal source of inspiration for human creativity. Whilst listening to this interpretation and thinking about swans, Raghuvir Mulgaonkar’s oils on paper portrait of a swan-necked woman popped into my head. The painting is called Untitled II. Mulgaonkar, who died in 1976, was an astonishingly prolific artist. Of him it was said he was “The artist whose brush never dried”. In this case, a related image flew in: that of the swan whose feathers never get wet. Shashank Subramanyam’s bamboo flute interpretation is a feast for the ears and the intellect. From Enchanting Hamsadhwani (Bamboo Records unnumbered, undated)

Evil Hearted You – Yardbirds

Between 1965 and 1968 The Yardbirds grew into one of Britain’s finest rock bands. For people who didn’t experience them at the time, their posthumous relationship probably was down to them having a succession of musicians who occupied that bloomin’ lead guitar chair – Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page – and what they did next. For anyone who experienced them at the time, a huge part of their appeal was the originality of their material, effects and tonal colours on their singles. The Graham Gouldman song Evil Hearted You was one such single.

This version, however, is a recording made for the BBC around August 1965. (The notes give only month and year.) Keith Relf’s voice is supple. Jim McCarty on drums and Chris Dreja on rhythm guitar support well. Paul Samwell Smith’s electric bass run is close to the single’s but not slavish. Beck is playing superlative guitar.

Above all, The Yardbirds have come to remind me of an old writer friend of mine, Comstock Lode‘s editor, John Platt (1952-2001). In 1983 the book he co-wrote with Jim McCarty and Chris Dreja about The Yardbirds was published. When I walk by Eel Pie Island at Twickerham, Platt – it was schoolboy surname stuff but we enjoyed it – often enters my thoughts. He wrote about the Eel Pie scene as well. Plus, as I write, there are posters up in town for The Yardbirds (featuring McCarty and Dreja) playing The Live Room at Twickenham Stadium on Friday 25th March 2011. From Yardbirds On Air (Band Of Joy BOJCC 200, 1991)

Philip Hoare’s obituary of John Platt of Wednesday, 23 May 2001 is at www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/john-platt-729142.html

Plus www.theyardbirds.com

Fallin’ Ditch – Don Van Vliet

Fallin’ Ditch – Don Van Vliet

When Don Van Vliet died on 17 December 2010, there was an outpouring of obituaries. They concentrated on his time as Captain Beefheart. The coverage was pretty much predictable and it pretty much concentrated on his recordings, especially – and totally understandably – on Troutmask Replica (1969). It was one of those records that changes lives or divides minds. It is also one of those take-time-to-know-her-love’s-not-an-overnight-thing things. It had spent years in my head and it was good.

I learned that Don Van Vliet was attending the opening of his Waddington Galleries exhibition, held between 3-26 April 1986 in London’s Cork Street. A quick transatlantic call to my editor Mike Farrace at Pulse! secured a commission. As an upshot I got to spend several hours at the gallery opening with Don Van Vliet, prior to doing an interview the next day. What struck me was how approachable, open and forthcoming he was. Nothing whatsoever like the reputation that had preceded him.

This recitation appears on the limited edition CD with the book published for a later exhibition. It was a travelling exhibition that peregrinated from Bielefeld in Germany (27 November 1993-16 January 1994) to Odense in Denmark (11 February-10 April 1994) and then to Brighton on England’s South Coast (3 September-13 November 1994). It and its other recitations capture his speaking voice, though it has aged slightly from the one I listened to in 1986.

Fallin’ Ditch opens, “When I get lonesome the wind begin t’moan/When I trip fallin’ ditch/Somebody wanna throw the dirt right down.” It’s a song lyric in itself. I reviewed the book in Mojo. PS: the Pulse! interview never happened but I had enough contemporaneous notes and quotes from him to write an article. From Stand Up To Be Discontinued in Don Van Vliet (Cantz Verlag Ostfildern, ISBN 3-9801320-3-X, 1993)

Autumn Leaves – Rickie Lee Jones

You think that wonderful song Chuck E.’s In Love in such a stripped back performance with only Rob Wasserman on bass is going to clinch it. Then she does Autumn Leaves, again with Wasserman. From Naked Songs (Reprise 9362-45950-2, 1995)

Mushika Vahana – Swamy Haridhos & Party

Over several decades I have listened to many recordings of bhajans – Hindu hymns – but Bengt Berger’s recording at Gita Govinda Hall in Bombay on 1 January 1968 capturing the South Indian-style of worship is one I count as one of the greatest and most natural I have ever heard. There is a real sense of presence and congregation as no other recording of this kind I have ever heard captures. It is articulate musically and radiates a presence. Mushika Vahana is but one example. Muthunathan Bhagvatar accompanies on harmonium, P.S. Devarajan on mridangam, K.V. Ramani on tabla and K. Shivakumar on violin. I would go so far as to say that anybody with an interest in Indo-Pakistani culture, religiosity or music should try to listen to this album. No caveats, quibbles or qualifying remarks. From Classical Bhajans (Country & Eastern CE14, 2010)

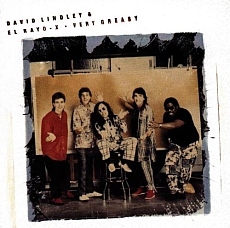

Papa Was A Rolling Stone – David Lindley & El Rayo-X

Papa Was A Rolling Stone – David Lindley & El Rayo-X

It was towards the end of 2010. Gliding through Chinatown (just south of Shaftesbury Avenue and Soho), my esteemed colleague Tony Russell and I walked past Lee Ho Fook’s of Werewolves of London fame. You know those lines of Warren Zevon’s? “I saw a werewolf with a Chinese menu in his hand/Walking through the streets of Soho in the rain/He was looking for a place called Lee Ho Fook’s/Going to get himself a big dish of beef chow mein.” Well, Lee Ho Fook’s is gone now and the new restaurant no longer has that joyously fading sign in its window about Warren Zevon, Lee Ho Fook and Werewolves of London. Or indeed any sign about a piece of Anglo-American special friendship history. Dastards despoiling cultural history, say the grumblers. I digress because I can and got an Ordinary Certificate in Digression.

Anyway, that walk along Gerrard Street planted the seed of an urge to revisit Very Greasy‘s extraordinary rendition. But Werewolves got elbowed out by the track that precedes it. Papa Was A Rolling Stone has a nasty, dirty sound. In an interview with Richard Grulla in the December 1988 issue of Guitar World, it is mentioned that Lindley got his sound from a Supro lap steel through a Howard Dumble amp on both Papa and Werewolves. Probably true but Lindley is the Q-Ship of guitars and amps. (That’s an original line so credit me if you really must steal.) Play it soft, play it loud, the Lindley and El Rayo-X’s rendition of the James Brown soul hit genuinely adds new dimensions to the familiar song. Lindley, Jorge Calderón, Walfredo Reyes, Ray Woodbury and Wm ‘Smitty’ Smith are the X-Boys. From the Linda Ronstadt-produced Very Greasy (Elektra 960 768-2, 1988)

As Soon As This Pub Closes – Cyril Tawney

Cyril Tawney (1930-2005) was the sort of chap you could lose a day or three with. He was a marvellous raconteur and wit, by turn, droll, deadpan and erudite. He is best known for his own songs – such as Five Foot Flirt, Lean And Unwashed Tiffy and Sammy’s Bar – and his West Country traditional folksong repertoire. Sometimes, however, other writers’ songs snuck into his repertoire. This song is one by Alex Glasgow (1935-2001). It is a comical revolutionary song and Cyril sings it well. It is not just comical, it is heavily ironical. In a perverse sort of way, it deserves to be sung as a shaming song, which is how I receive it from Cyril. It deserves to be far more widely sung and not just in the run-up to closing time. From The Song Goes On (ADA Recordings ADA108CD, 2007)

The Snow It Melts The Soonest – Anne Briggs

The Snow It Melts The Soonest – Anne Briggs

“Oh, the snow it melts the soonest when the winds begin to sing,” is how it begins. Anne Briggs remains a huge inspiration and mystery to succeeding generations. She just got it right. This is one of her signature songs. It is a layered one about love set firmly in the natural world. Its seasonal movements and references to wild life reflect her passions for Nature. She sings it unaccompanied, three seasons (autumn isn’t mentioned) distilled into four verses.

The image here is of a wild plant called pellitory of the wall (Parietaria officinalis) beside the Thames at Old Isleworth, Middlesex. It likes walls and, unless you have an eye for botany, it looks pretty nondescript. Anne and I have walked the upper stretches of the tidal Thames, an area rich in plant diversity. Rivers are wildlife highways and natives mix with all manner of species from other places and continents. The snow part-melted and this pellitory of the wall emerged. It was Annie who first identified the plant for me. From Anne Briggs – A Collection (Topic Records TSCD504, 1999)

The pellitory of the wall image is © 2011 Ken Hunt/Swing 51 Archives. The copyright of all other images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers.

10. 1. 2011 |

read more...

[by Aparna Banerji, Jalandhar City] My delightful 10 this month are Canned Heat, Aarti Ankalikar, Raghubir Yadav and Bahdwai Village Mandali, Javed Ali and Chinmayi, Satinder Sartaaj, Farida Khanum, Silk Route, Udit Narayan and Alka Yagnik, Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia and, lastly, Pandit Birju Maharaj, Kavita Subramanium and Madhuri Dixit.

On The Road Again – Canned Heat

On The Road Again – Canned Heat

Much of the trickle of American popular music I have fell in my lap by default. Except for the few glitzy pop icons that MTV and Channel V introduced me to, I just stumbled upon most of the other guys through compilations by record labels that I picked up, on impulse, at local music stores. I had my share of disasters and disappointments, but chancing upon gems like this has made my life.

I didn’t have any clue about the history, status or popularity of the band that created this when I first heard this song (though now I think that was a blessing ’cause it helped me form an unbiased opinion). Everything about it – music, lyrics, especially the voice – hit me hard. It’s the 1968 Boogie with Canned Heat Liberty Records version and made me build my own little story around it.

I connected with the guy who sung it and thought of him as this little, free-spirited, dumb-wise, lonely guy who hates strangers. I wanted to join him on the road he was walking down on and tell him things are gonna be OK. And I thought he’d probably punch me in the nose the first time I do that, but eventually we might become friends.

Years later, I read about the band and smiled. I was happy that the whole world loved the song but was a bit disappointed too. They were too big to match my little guy illusion.

I love the way Al Wilson sings “out” and “long old lonesome road”. I try to ape the way he does it sometimes when I’m in the mood. I think no other voice can do as much justice to the character of the guy this song talks about. Bob Hite (harmonica), Henry Vestine (lead guitar), Larry Taylor (electric bass), Fito de la Parra (drums) and Wilson himself on slide guitar lend the on-the-road rhythm and feel to the song.

The Floyd Jones lyrics and composition which Wilson adapted to create this classic say: “My dear mother left me when I was quite young/She said, ‘Lord have mercy on my wicked son’.” From The Best College Classics Album in the World Ever (Virgin Records, 2001)

Chali pee ke nagar – Aarti Ankalikar

In the 1996 film Sardari Begum, this is the song that the daughter of Sardari Begum, the courtesan and thumri singer, hums to her dying mother on her request. It’s the most intimate mother-daughter moment that the two share in the movie. It is also one of my favourite on-video moments.

Based on Rāg Sindhi Bhairavi, the song talks about a bride who is parting with the land she was brought up in. The Sardari Begum context lends it so much irony and sadness. The composition itself is bittersweet and suggests tragedy and loss in spite of the fact that it talks about a bride.

Aarti Ankalikar lends her voice to the soundtrack version. Her vocals are mellow and soothing and at the same time filled to the brim with the force that is characteristic of Indian classical music. Vanraj Bhatia’s brilliant composition and with Ankalikar’s extraordinary voice make it one of the best classical vehicles that Bollywood ever doled out.

Javed Akhtar gives us the lyrics which say:

“Chali pee ke nagar

saj ke dulhan.”

(The decked up bride goes to the town of her husband.)

“Jhoole, peepal, amva, chanv

panghat, mele, galiyan, gaanv

babul, maiya, sakhiyan, angna

sab chor ke gori jaavat hai.”

(Swings, peepal trees, mangoes, shade/Wells [the word panghat means the place, usually the well, where women used to gather to fill their water pots], fairs, streets, villages/Father, mother, friends, courtyards/The fair bride leaves it all behind as she goes.) From Sardari Begum (Sony Music 504452 4, 2001)

Maiya Yashoda (Jamuna Mix) – Javed Ali and Chinmayi

Maiya Yashoda (Jamuna Mix) – Javed Ali and Chinmayi

India’s so big on Krishna sensibilities. He’s everywhere. Still there are some things I thought he could never fit with. If someone gave me the words of this song on paper and told me they were gonna give some solid techno treatment to it, I would have called the person a fool to their face. I thought all previous pieces of music which attempted to digitalise Krishna sounds, miserably failed. After hearing this I changed my stance; I lacked imagination.

A. R. Rahman comes out with another masterpiece. I would have bet this is bhajan or thumri material but he makes an immensely successful dance floor number out of it. Nowhere does it feel contrived or forced. It’s a pretty complex and imaginative tune and yet it sounds so simple. Rahman loves doing that.

To be fair, the song’s not over the top techno but an Indian sort of techno. It mixes the dandia and digital dance floor flavours in such an immensely beautiful manner that one’s left awestruck and wondering whether he/she should swing to the melody or groove to the beats. I even think there’s a folk tinge to the song.

The amazing, laughing and equally complex vocals are by Javed Ali and Chinmayi. The sitar (Asad Khan) and flute (Naveen Kumar and Navin Iyer) portions are also lovely. The deep, layered lyrics by Abbas Tyrewala, the director of the movie that this song comes from, say a lot more than what they actually say.

The gal says:

“Maiyya Yashoda mori gagri se Jamuna ke pul par maakhan, haan koi, re maakhan chura le gaya

ho maiyya yashoda kaise jaaun ghar Jamuna ke pul par maakhan haan koi, re maakhan chura le gaya

mori baanh modi, natkhat re,

kare dil ko jodi, natkhat re,

mori gagri phooti, natkhat re,

main bojh se chhooti, natkhat re,

mori thaame kalai us kinare le gaya.”

(Mother Yashoda, out of my earthen pot, on the bridge across [the River] Yamuna’s, the butter, yes, someone stole the butter/Mother Yashoda, how do I go home?/On the bridge across the Yamuna, the butter, yes. someone stole the butter/Twisted my arm, mischievous him/Bound heart with me, mischievous him/My earthen pot broke, mischievous him/I was relieved of the burden, mischievous him/Grabbed my wrist and took me to that shore.)

The guy replies:

“Maiya Yashoda sach kehta hoon, main Jamuna ke pul par maakhan ki gagri se maakhan bachane gaya.”

(Mother Yashoda, I talk truth, I went to the bridge across the Yamuna to save the butter from the earthen pot that held the butter.) From Jhootha Hi Sahi (Saregama India Ltd. CDF 112325, 2010)

Sapnay – Silk Route

This is one band that I have ‘always’ liked for its rich music and visuals (videos). Their work has always been path-breaking. Their music smells of hills and mists. It says simple things, simply but the mood they create always spills on to you. Leaves me mellow for hours, even after I have switched the music off.

This one, from their second album Pehchaan (2000), especially, gives me goose bumps. Mohit Chauhan does the vocals, guitar and haunting harmonica. Kem Trivedi’s on keyboard. Kenny Puri’s on percussion and drums.

It says:

“Sapnay hain sooni ankhen

jaane kyon kho gaye

socha tha sahil pe milega

thehra sa ek pal.”

(Dreams in empty eyes/Don’t know why they got lost/Had thought on the shore we’d meet/A moment that stands still.) From Boyz to Men (BMG Crescendo (India) Ltd. 51250, 2001)

Kuch Kuch Hota Hai – Udit Narayan and Alka Yagnik

The ultimate happy-go-lucky Bollywood fare. Reminds me of Archie comics and the time I used to hang movie posters in my room.

Love the ghada (earthen pot) percussion in this eternal love song which says:

“Kya karun haaye

kuch kuch hota hai.”

(Oh what do I do/Something something happens [literally: “that’s how it sounds”].)

Udit Narayan and Alka Yagnik in their sweet Bollywood voices sing Jatin Lalit’s composition and Sameer’s lyrics. From Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (Sony Music 491740 4, 1998)

Paani Panjan Daryawan Wala – Satinder Sartaaj

Paani Panjan Daryawan Wala – Satinder Sartaaj

This is from the guy who brought hope back to the Punjabi music industry. He stepped in at a time when the ‘thinkers’ were growing exceedingly sick of the multitude of cheesy duets and other tired fare that had dwarfed the soul sounds which Punjab has always been so proud of.

Sartaaj walked in, dressed in salwar kurta and a turban tied over open hair like the Sufis. He usually performed seated on the floor and usually to hushed concerts (a rarity in Punjab). His songs talk about Punjab, Love and God. They respect life and urge others to do so. They are soft and soulful. This one’s no exception. It worries about Punjab and its youth, about artificiality and feuds.

It says:

“Pani panjan daryawan wala nehri ho gaya

munda pind da si shehar aa ke shehari ho gaya

O yaad rakhda vaisakhi ohne vekheya hunda je

rang kankan da hare ton sunehri ho gaya.”

(The water of the five rivers now flows in canals/The guy from the village went to the city and turned urban/He would have remembered Baisakhi [Punjab’s harvest festival] if he’d seen/The colour of the wheat crop turn from green to golden.)

“Tera khoon thanda ho gaya ai khaulda nahi e

ji eho virse da masla makhaul da nahi e

tennu aje nai khayal pata odon hi lagguga

jadon aap hatthi choya shehad zehri ho gaya.”

(Your blood has grown cold, it doesn’t heat up anymore/This matter about heritage isn’t something to be laughed at/You don’t give it a thought now but you will realise things/When honey that your own hands drew turns to poison.)

The lyrics are by Sartaaj and the music’s by Jatinder Shah. From Sartaaj (Moviebox Records Pvt. Ltd. Sr No. 1162, 2010)

Rāg Jait (Vibhas Ang) – Hariprasad Chaurasia

As a kid, when some koel used to call out sitting on some tree near my home, I used to call out after it, aping it. If the koel responded, I used to be very happy. I used to keep calling out to it until it got bored of me. It mostly did before I did. There was something beckoning, pleading, conversational about the way it called out. As if it said, “yes”, “what?”, “I’m here”.

Hariprasad Chaurasia’s flute reminds me of that koel. His flute talks, beckons, asks me to listen, tells me tales and does it all so sweetly. He does it in Rāg Jait (Vibhas Ang) using the pa, ga, re, sa combination, which is common to the Purvaangs (first halves) of both the Jait and Vibhas ragas, with just a tanpura for accompaniment. (The only difference between Jait and Vibhas is that Jait uses dha shudh and Vibhas uses dha komal. But Panditji uses dha shudh so he sticks to the basic Jait combination. From Hariprasad Chaurasia (HMV STCS 850135, 1982)

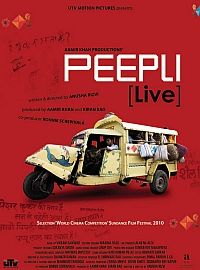

Mehngai Dayain – Raghubir Yadav and Bhadwai Village Mandali

Mehngai Dayain – Raghubir Yadav and Bhadwai Village Mandali

Everything, every single thing about the movie that this track comes from – and its soundtrack – is awesome. It’s one of the most unlaboured (seemingly) and yet chilling ways in which Bollywood has ever dealt with big issues and the irony hanging over them. I would love to, but can’t talk about it all, so, for the moment, I choose Mehngai Dayain.

The track is a folksy take on inflation and the most effective that I’ve ever come across. When it came to folk, Raghubir Yadav had always been one of my personal favourites. I had heard him hum little somethings as an actor in the film Rudali (as Sanichari’s elusive son Budhwa) and in Maya Memsaab (as the crazed street-beggar). He kept making appearances as a vocalist in large and small chunks on some sound tracks too. On every occasion he loaded the track or moment with the village wisdom in his voice.

But somehow it felt he was never taken as seriously as a vocalist, as he should have been. This, however, is different. He makes himself heard (thanks to the film crew for that too) and his rendering is immensely satisfying. This song is a proof of his musical wit. The village guys that he collaborates with – The Bhadwai Village Mandali – are, like him, masters in their art. The song has been written and composed by them. They are a group of part-timers who do music on festive occasions in the village, using traditional instruments, as the CD notes tell me. The song’s devoid of pretence and gets us nostalgic in the delightful way it gets village sounds and words flooding in. Like the old days. Raghubir Yadav and the Bhadwai Village Mandali sit in the shade of a tree in the village square (the recording was done on sync sound as the film crew shot) and sing:

“Sakhi saiyan to khoob hi kamaat hain

mehangayee dayain khaaye jaat hai.”

(Lady friend, my husband earns a lot but the inflation witch eats it all up.)

“Soyabeen ka kabe haal

garmi se pichke hain gaal

gir gaye patte, pak gaye baal

aur makka – ji-ji-ji-bhi kha gayee maat hai

mehngai dayain khaye jaat hai.”

(What does one say of soya beans?/The cheeks have sunk with the heat/The leaves have fallen, the hairs have ripened/And corn, yes, corn has lost the battle too/The inflation witch eats it all up.) From Peepli Live (Super Cassettes Industries Ltd. SFCD 1-1600, 2010)

Kahe Ched Mohe – Birju Maharaj, Kavita Subramaniam and Madhuri Dixit

All things classical are writ large over this song. It starts with aroused sarangi and forceful tabla bols (mouth percussion based on the matras – beats – of the tabla), followed by the soul stirring voice of Pandit Birju Maharaj adulating a woman’s beauty. The song is in Rāg Puriya Dhanashree and brims over with the rhythmic genius that is largely responsible for the drama and aggression that marks Indian classical dance. And since it is served on the Bollywood platter, the drama gets to a whole new level.

Krishna’s an integral element in this one too (told you). Kavita Subramaniam (Krishnamurthy) soon arrives on the scene asking him why he teases her. In the interplay between percussion and Subramaniam’s melodious vocals, Madhuri Dixit renders her conversational, lyrical interludes from time to time.

The song’s composition and lyrics are by Pandit Birju Maharaj. He is also the choreographer for the video version of the song where Chandramukhi, the courtesan, dances to a melancholy Devdas. I love it most for Pandit Birju Maharaj’s voice in the beginning. I wish there was more of him in it.

It says:

“Kahe ched mohe garwa lagaye

Nand ko lal aiso dheeth

barbas mori laaj leenhi

binda Shaam manat naahi

kaase kahun main apne jiya ki, sunat nahi, maayi.”

(Why does he tease me? He embraces me/Nand’s son is such a rogue/He robs me of my honour/Wicked Shaam doen’t pay heed/How do I say what’s in my heart? he doesn’t listen, mother.) From Devdas (Universal Music 6337 333, 2002)

Gulon ki baat karo – Farida Khanum

Gulon ki baat karo – Farida Khanum

Ghazals are one of the reasons I wonder if I had a past life. The atmosphere they create does something intense to me. An I-was-there feeling. I have been listening to this one since I was a kid. My mother played it on tape along with many other of Farida’s precious songs. I love its composition. It’s about nostalgia and class.

It says:

“Gulon ki baat karo

gul rukhon ki baat karo

bahaar aayi hai

guncha labon ki baat karo.”

(Talk about flowers/Talk about flowering trees/Spring has come/Talk about blossoming lips.)

The music’s by Farida and Akhtar Hussain. Faiz Ahmed Faiz gives us the words. From The Best of Farida Khanum (HMV HTCS 04B 4480, 1992)

The copyright of the images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers. The copyright of the lyrics lies with the associated copyright holders.

3. 1. 2011 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] An Evening of Political Song, explained the Southbank literature, “drew upon a rich history of political song” before, sigh, spoiling things slightly by lamely billing this night in Richard Thompson’s Meltdown as “a night of songs in the key of revolution and protest”. Still, mustn’t grumble, ‘political song’, as dictionary definitions go, is about as precise as ‘folk song’ in its handy one-size-fits-all solution to issues that just won’t go away.

[by Ken Hunt, London] An Evening of Political Song, explained the Southbank literature, “drew upon a rich history of political song” before, sigh, spoiling things slightly by lamely billing this night in Richard Thompson’s Meltdown as “a night of songs in the key of revolution and protest”. Still, mustn’t grumble, ‘political song’, as dictionary definitions go, is about as precise as ‘folk song’ in its handy one-size-fits-all solution to issues that just won’t go away.

The night provided a blast of political song designed to engage and stimulate – or even to provoke to the point of offending – while avoiding any why-oh-why? breast-beating material. This though isn’t a concert review. It focuses on three songs as snapshots of what political song today can embrace

Tom Robinson’s take on Steve Earle’s John Walker’s Blues threw the fat into the fire. It focuses on John Walker Lindh, a US national who joined the Taliban and had the shit-luck to get captured. A paradigm political song, it has attracted outright censure and considered debate. Here Earle is no talking newspaper and, beyond the Talibanery, he gets down to motivation for such a heinous act of betrayal of the American Dream. As Robinson sang the exit lines – “But Allah had some other plan, some secret not revealed/Now they’re draggin’ me back with my head in a sack/To the land of the infidel” – he left the audience with much food for thought.

Shock tactics can also work, so long as they are detonated sparingly. Take stand-up comic Denis Leary’s jolly sing-along recording I’m An Asshole with its first-person bead-roll of me-me-me-not-you-me selfishness, like parking in “handicapped spaces”. Nuanced humour is not Leary’s forte, so using ‘handicapped’ was probably accidental irony, but he knows how to play the cringeworthy card. Harry Shearer – the voice of Mr. Burns, Smithers and Ned Flanders in the English-language version of The Simpsons and the, ahem, well-toned body of Derek Smalls in Spinal Tap – delivered confrontation of another kind. Deaf Boys, on which Thompson and Judith Owen did back-up vocals and finger-clicks, lambasts paedophiliac Catholic priests abusing deaf boys entrusted to them. Lines like “Deaf boys can’t hear me coming.” were genuinely shocking. It really hit a raw nerve in me.

The grand finale hit raw nerves of a different kidney. Ewan MacColl’s Moving On Song is a telling plea for equality of treatment. It’s originally from the 1964 Radio Ballad, The Travelling People. A full complement took the stage but my eyes and ears stayed fixed on Norma Waterson as she lived out the song. At the time of the concert I was researching and writing an essay for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography about the Scots Traveller story-teller and sangster Duncan Williamson making the song with its “Go! Move! Shift!” chorus sound all too horribly pertinent.

To see clips of what was going on, visit http://meltdown.southbankcentre.co.uk/2010/events/an-evening-of-political-song/

Photograph of Harry Shearer, © and courtesy of the Southbank press office.

Ken Hunt’s column RPM about political and socially engaged song appears issue to issue in R2.

http://www.rock-n-reel.co.uk/ and http://www.facebook.com/R2magazine

20. 12. 2010 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Polish revue artist, singer and actress Irena Anders, born Irena Renata Jarosiewicz on 12 May 1920 in Bruntál, in what is nowadays the Czech Republic, went under the stage name of Renata Bogdańska. Her father was a Rutherian pastor while her mother came from the Polish gentry. She studied music formally at the National Academy of Music in Lviv. The invasion of Poland in September 1939 put paid to her studies and over the next few years the tides of war and the various fortunes of Poland, its citizens and army determined her own life’s course.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Polish revue artist, singer and actress Irena Anders, born Irena Renata Jarosiewicz on 12 May 1920 in Bruntál, in what is nowadays the Czech Republic, went under the stage name of Renata Bogdańska. Her father was a Rutherian pastor while her mother came from the Polish gentry. She studied music formally at the National Academy of Music in Lviv. The invasion of Poland in September 1939 put paid to her studies and over the next few years the tides of war and the various fortunes of Poland, its citizens and army determined her own life’s course.

Her first husband, Gwidon Borucki, led a morale-boosting troupe entertaining Polish forces fighting on the side of the Allies. Poles of the 2nd Polish Division under the command of General Władysław Anders played an especially important role in the hard-fought and bloody taking of the Nazi-occupied strongpoint at Monte Casino in Italy in 1944. Out of this campaign emerged the patriotic song Czerwone maki (na Monte Cassino) (‘Red Poppies On Monte Cassino’), which had a setting by Alfred Schütz of Feliks Konarski’s words. The song, composed in May 1944, was forged in the heat of that battle while the poppy image also evoked the symbol of trench warfare during the Great War. Czerwone maki was sung following the capture of the monastery and while there is a certain lack of clarity about Renata Bogdańska’s participation at this point, it became a song closely associated both with her, the anti-fascist movement and Polish patriotism.

She went on to marry Władysław Anders, settle in Britain, appear on radio and in films and in 2007 received Poland’s second highest civilian decoration for her contributions to Polish culture. She died on 29 November 2010 in London.

19. 12. 2010 |

read more...

« Later articles

Older articles »

[by Ken Hunt, London] Planning a trip to England, Scotland and/or Wales? Hoping your visit coincides with some musical adventures? The highly recommended Spiral Earth guide is the ideal place to start planning your time and trip.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Planning a trip to England, Scotland and/or Wales? Hoping your visit coincides with some musical adventures? The highly recommended Spiral Earth guide is the ideal place to start planning your time and trip. [by Ken Hunt, London] East German rock music, nowadays known as Ost-Rock (Ost means east), has never had a champion outside the old East. Sure, Julian Cope got wiggy and witty with Krautrock in all its Can, Kraftwerk and Ohr-ishness. But aside from, say, coverage in the Hamburg-based magazine Sounds in the 1980s and Tamara Danz (1952-1996) – and Silly’s lead singer’s fleeting appearance in the last edition of Donald Clarke’s Penguin Encyclopedia of Popular Music – Ost-Rock got short shrift outside its place of origin, the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Götz Hintze’s Rocklexikon der DDR (2000) and Alexander Osang’s Tamara Danz (1997) biography have redressed the balance somewhat. But Hintze and Osang wrote accounts in German. Probably, no English-language champion will take up Ost-Rock‘s colours now.

[by Ken Hunt, London] East German rock music, nowadays known as Ost-Rock (Ost means east), has never had a champion outside the old East. Sure, Julian Cope got wiggy and witty with Krautrock in all its Can, Kraftwerk and Ohr-ishness. But aside from, say, coverage in the Hamburg-based magazine Sounds in the 1980s and Tamara Danz (1952-1996) – and Silly’s lead singer’s fleeting appearance in the last edition of Donald Clarke’s Penguin Encyclopedia of Popular Music – Ost-Rock got short shrift outside its place of origin, the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Götz Hintze’s Rocklexikon der DDR (2000) and Alexander Osang’s Tamara Danz (1997) biography have redressed the balance somewhat. But Hintze and Osang wrote accounts in German. Probably, no English-language champion will take up Ost-Rock‘s colours now. Finisterre – June Tabor

Finisterre – June Tabor Love Song For The Dead Ché – The United States of America

Love Song For The Dead Ché – The United States of America Love Song For The Dead Ché is under three-and-a-half minutes in length. In mood and style it contrasted with the album’s other material like their cheeky sound-collage The American Way of Love, harder driving material like The Garden of Earthly Delights or the social satire of I Won’t Leave My Wooden Wife For You, Sugar. Love Song For The Dead Ché is quieter, more meditative. At the time there was only one Ché in the news but this song’s wistfulness maintains an ambiguity.

Love Song For The Dead Ché is under three-and-a-half minutes in length. In mood and style it contrasted with the album’s other material like their cheeky sound-collage The American Way of Love, harder driving material like The Garden of Earthly Delights or the social satire of I Won’t Leave My Wooden Wife For You, Sugar. Love Song For The Dead Ché is quieter, more meditative. At the time there was only one Ché in the news but this song’s wistfulness maintains an ambiguity. Kaddish – Clara Rockmore

Kaddish – Clara Rockmore No Time For Love

No Time For Love – Christy Moore with Declan Sinnott

– Christy Moore with Declan Sinnott [by Ken Hunt, London] The Bengali singer Suchitra Mitra died on 3 January 2011 at her home of many years, Swastik on Gariahat Road in Ballygunge, Kolkata. She was famed as one of the heavyweight interpreters of the defining Bengali-language song genre form called Rabindra sangeet – or Rabindrasangeet (much like the name Ravi Shankar can also be rendered Ravishankar). ‘Rabindra song’ is an eloquent, literary, light classical song form, derived from the name of the man who ‘invented’ it, Rabindranath Tagore, the winner of the 1913 Nobel Prize for Literature.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Bengali singer Suchitra Mitra died on 3 January 2011 at her home of many years, Swastik on Gariahat Road in Ballygunge, Kolkata. She was famed as one of the heavyweight interpreters of the defining Bengali-language song genre form called Rabindra sangeet – or Rabindrasangeet (much like the name Ravi Shankar can also be rendered Ravishankar). ‘Rabindra song’ is an eloquent, literary, light classical song form, derived from the name of the man who ‘invented’ it, Rabindranath Tagore, the winner of the 1913 Nobel Prize for Literature. [by Ken Hunt, London] Bengal’s popular arts lost two of its major figures on 17 January 2011.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Bengal’s popular arts lost two of its major figures on 17 January 2011. [by Ken Hunt, London] One of my fondest memories of Britain’s specialised music magazine scene of the 1980s into the 1990s is how little ego and rivalry there was for the most part. There were a couple of exceptions (no names, no pack drill) and, strange though it may seem, not a single ornery person from that bunch stayed the course within music criticism. Keith Summers wrote about music, collected it (as in, made field recordings of such as Jumbo Brightwell, the Lings of Blaxhall, Cyril Poacher and Percy Webb as well as later contributing to Topic’s multi-volume series Voice of the People) and published magazines about it. He had the fall-back trade of accountant that funded his passions.

[by Ken Hunt, London] One of my fondest memories of Britain’s specialised music magazine scene of the 1980s into the 1990s is how little ego and rivalry there was for the most part. There were a couple of exceptions (no names, no pack drill) and, strange though it may seem, not a single ornery person from that bunch stayed the course within music criticism. Keith Summers wrote about music, collected it (as in, made field recordings of such as Jumbo Brightwell, the Lings of Blaxhall, Cyril Poacher and Percy Webb as well as later contributing to Topic’s multi-volume series Voice of the People) and published magazines about it. He had the fall-back trade of accountant that funded his passions. [by Ken Hunt, London] Winter draws on in London but on the fictitious tropical island the sun is shining. Helping to banish gloom this month is a rather fine selection of music. Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, this month’s haul of traveller’s tales embraces Martin Simpson, Ella Ward, Yardbirds, Shashank, Don Van Vliet, David Lindley & El Rayo-X, Rickie Lee Jones, Swamy Haridhos & Party, Cyril Tawney and Anne Briggs.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Winter draws on in London but on the fictitious tropical island the sun is shining. Helping to banish gloom this month is a rather fine selection of music. Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, this month’s haul of traveller’s tales embraces Martin Simpson, Ella Ward, Yardbirds, Shashank, Don Van Vliet, David Lindley & El Rayo-X, Rickie Lee Jones, Swamy Haridhos & Party, Cyril Tawney and Anne Briggs. The Swastika Song – Martin Simpson

The Swastika Song – Martin Simpson Hamsadhwani – Shashank

Hamsadhwani – Shashank Fallin’ Ditch – Don Van Vliet

Fallin’ Ditch – Don Van Vliet Papa Was A Rolling Stone – David Lindley & El Rayo-X

Papa Was A Rolling Stone – David Lindley & El Rayo-X The Snow It Melts The Soonest – Anne Briggs

The Snow It Melts The Soonest – Anne Briggs On The Road Again – Canned Heat

On The Road Again – Canned Heat Maiya Yashoda (Jamuna Mix) – Javed Ali and Chinmayi

Maiya Yashoda (Jamuna Mix) – Javed Ali and Chinmayi Paani Panjan Daryawan Wala – Satinder Sartaaj

Paani Panjan Daryawan Wala – Satinder Sartaaj Mehngai Dayain – Raghubir Yadav and Bhadwai Village Mandali

Mehngai Dayain – Raghubir Yadav and Bhadwai Village Mandali Gulon ki baat karo – Farida Khanum

Gulon ki baat karo – Farida Khanum

[by Ken Hunt, London] An Evening of Political Song, explained the Southbank literature, “drew upon a rich history of political song” before, sigh, spoiling things slightly by lamely billing this night in Richard Thompson’s Meltdown as “a night of songs in the key of revolution and protest”. Still, mustn’t grumble, ‘political song’, as dictionary definitions go, is about as precise as ‘folk song’ in its handy one-size-fits-all solution to issues that just won’t go away.

[by Ken Hunt, London] An Evening of Political Song, explained the Southbank literature, “drew upon a rich history of political song” before, sigh, spoiling things slightly by lamely billing this night in Richard Thompson’s Meltdown as “a night of songs in the key of revolution and protest”. Still, mustn’t grumble, ‘political song’, as dictionary definitions go, is about as precise as ‘folk song’ in its handy one-size-fits-all solution to issues that just won’t go away. [by Ken Hunt, London] The Polish revue artist, singer and actress Irena Anders, born Irena Renata Jarosiewicz on 12 May 1920 in Bruntál, in what is nowadays the Czech Republic, went under the stage name of Renata Bogdańska. Her father was a Rutherian pastor while her mother came from the Polish gentry. She studied music formally at the National Academy of Music in Lviv. The invasion of Poland in September 1939 put paid to her studies and over the next few years the tides of war and the various fortunes of Poland, its citizens and army determined her own life’s course.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Polish revue artist, singer and actress Irena Anders, born Irena Renata Jarosiewicz on 12 May 1920 in Bruntál, in what is nowadays the Czech Republic, went under the stage name of Renata Bogdańska. Her father was a Rutherian pastor while her mother came from the Polish gentry. She studied music formally at the National Academy of Music in Lviv. The invasion of Poland in September 1939 put paid to her studies and over the next few years the tides of war and the various fortunes of Poland, its citizens and army determined her own life’s course.