Articles

[by Ken Hunt, London]  Ali Akbar Khan shuffled on stage with a walking stick, reasonable given he was one week away from 81. By night’s end, all memories of the frail character that had mounted the dais at the concert’s beginning had vanished. Swapan Chaudhuri, one of the most exceptional tabla players alive, provided the percussive accompaniment – a job a bit like catching eels with bare hands. He has an uncanny knack of being able to match and bat back this sarodist’s glorious spontaneity. Alam Khan was the second, junior sarodist but he coped brilliantly with his father’s senior waywardness. Ken Zuckerman, one of Khan’s senior disciples and head of his Basel college, and Malik Khan, Khan’s next son down after Alam, provided the drone accompaniments.

Ali Akbar Khan shuffled on stage with a walking stick, reasonable given he was one week away from 81. By night’s end, all memories of the frail character that had mounted the dais at the concert’s beginning had vanished. Swapan Chaudhuri, one of the most exceptional tabla players alive, provided the percussive accompaniment – a job a bit like catching eels with bare hands. He has an uncanny knack of being able to match and bat back this sarodist’s glorious spontaneity. Alam Khan was the second, junior sarodist but he coped brilliantly with his father’s senior waywardness. Ken Zuckerman, one of Khan’s senior disciples and head of his Basel college, and Malik Khan, Khan’s next son down after Alam, provided the drone accompaniments.

The section before the intermission (half had no place here) was an interpretation of ‘Hindol-Hem’ shaped with all the depth, authority and daring of a senior maestro. It coiled like a krait drawing life and energy from the spring sunshine. It was one of those performances during which Time becomes an observer. Typically, Khan himself lost himself, hence the remark about half. Announcing only that he would know what he was playing when he was playing it, he concluded with a ‘Piloo’- or ‘Mishra Piloo’-based piece with a dash of ‘Zila Kafi’ in the less demanding ragamala (garland of ragas) performance style. Before long, the music took over and began playing him. It produced a performance of unbelievable intensity, imagination and stamina. Its outrageousness had me laughing out loud at the sheer outrageousness of his playing and phrasing. A night imprinted in the grey cells.

This commissioned review, written directly after the concert, never ran owing to space restrictions. Ustad Ali Akbar Khan died in San Anselmo, California on 18 June 2009. Shortly before going on stage he learnt that he was unlikely to receive his fee in full and he channelled that discovery into one of the most intense performances I have ever seen from any musician. After the concert there literally was blood on his sarod’s strings.

21. 6. 2010 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Even though this month’s choices are skewed and heavily informed by volumes 7-9 in Smithsonian Folkways’ Music of Central Asia series, in terms of preference, as usual, there is no order implied and no order to be inferred. As ever, the common link to May 2010’s GDDs is that this is music that stuck around. This month we meet, greet and embrace Jackson Browne David Lindley, Barb Jungr, the Kronos Quartet with Alim & Fargana Qasimov, Asha Bhosle, Les Byrds, Sirojiddin Juraev, Homayun Sakhi and Rahul Sharma, Jiři Kleňha and Neneh Cherry and Youssou N’Dour.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Even though this month’s choices are skewed and heavily informed by volumes 7-9 in Smithsonian Folkways’ Music of Central Asia series, in terms of preference, as usual, there is no order implied and no order to be inferred. As ever, the common link to May 2010’s GDDs is that this is music that stuck around. This month we meet, greet and embrace Jackson Browne David Lindley, Barb Jungr, the Kronos Quartet with Alim & Fargana Qasimov, Asha Bhosle, Les Byrds, Sirojiddin Juraev, Homayun Sakhi and Rahul Sharma, Jiři Kleňha and Neneh Cherry and Youssou N’Dour.

The Crow On The Cradle – Jackson Browne David Lindley

The Crow On The Cradle – Jackson Browne David Lindley

This is the sort of musical tastiness that prompts the unwary to say that if there is a tastier track released in [gentle reader, add the year you’re reading this], they will eat polyester garments, assisted only by their hot sauce or condiment of choice and a couple of lubricating Pacificos to fend off the odd rictus. Personally, not being of a polyester-chomping bent, I would not enjoy the experience, even though wise men have said one can cram several portions of the aforementioned stuff into one’s mouth in one go. So, it is with deep regret that I inform you that Browne y Lindley deliver a lorryload of taunting temptations on their superlative 2010 offering, recorded on their Spanish tour in March 2006.

By London, with each gig impromptu and rehearsals deliberately avoided, their performances were full of spontaneous touches and ripples. The Crow On The Cradle is one of Sydney Carter’s finest songs. This version is prime quality stuff. The performance has an immediacy that is startling while its lyrical content is the stuff of timelessness. Sydney Carter must have known that when he wrote the song. Unhappily he had not foreseen what would happen when Browne and Graham Nash (con Lindley) covered it at a 1979 MUSE concert and it appeared on the set, No Nukes – sales of which were assisted by contributions from James Taylor, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band, Crosby, Stills & Nash. (The presence of Sweet Honey In The Rock and Gill Scott-Heron cannot be gainsaid either.) Carter told me that the unexpected influx of royalty money caused him all manner of grief. For years he had to explain to the tax people that it was an aberration. He wasn’t complaining too loudly. Last, there is the no ampersand or ‘and’ between their names. This is music made on an equal footing. As Sydney Carter’s song so eloquently demonstrates. From Love Is Strange (Inside Recordings INR5111-0, 2010)

www.jacksonbrowne.com

www.davidlindley.com

www.insiderecordings.com

Once In A Lifetime – Barb Jungr

This is the opening track of an outstanding collection that Barb Jungr calls ‘The New American Songbook’. While other interpreters add retreads to the old American Songbook – or in the case of Tony Bennett continues to do it his way, in his own signature style – she demonstrates that the Songbook is expanding rather than its girth is expanding. On Once In A Lifetime she is not fumbling for life-signs from stricken old songs: she is fingering the pulse on a new intake of songs. Apologies if the metaphor doesn’t do it for you. Why? Because Barb Jungr knows how to quicken a pulse and how to breathe new breath into a song.

Her decision to cover this David Byrne and Brian Eno song is a bold one. The first time I heard Barb Jungr sing this song was on the BBC Radio 4 programme Woman’s Hour with accompaniment stripped back to piano. It seemed that she had hit upon a different way to do justice to this Talking Heads mainstay. The album version, produced by Barb Jungr & Simon Wallace, has the touch of a jeweller or watchmaker. She cuts and turns the facets in the song in ways that cast, reflect and refract new light. The inclusion of Clive Bell’s shakuhachi and flute is inspired and Simon Wallace’s piano watery and flowing. An interpretion to linger in the memory. From The Men I Love (Naim Label naimcd 144, 2009)

www.barbjungr.co.uk

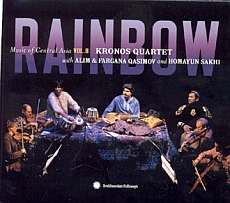

Köhlen Atim – Kronos Quartet with Alim & Fargana Qasimov

Köhlen Atim – Kronos Quartet with Alim & Fargana Qasimov

When they debuted this composition at the Barbican’s Ramadan Nights festival celebrating Ramadan and the start of Eid ul-Fitr on 26 September 2008, nobody needed, cue Sting, to be an illegal or legal Azeri-speaking alien in London to get what Köhlen Atim (‘My Spirited Horse’) was all about. It is a horsey song that goes from a trot to a canter to a gallop. All bets are off when it comes to this performance. It is a clear winner. From Music of Central Asia Vol. 8 – Rainbow (Smithsonian Folkways SFW CD 40527, 2010)

Log Cabin Home In The Sky – The Incredible String Band

Log Cabin Home In The Sky is one of those songs that enlivened 1968, the stuff to sing after last orders on the way home from the pub. Mike Heron’s lyrics are amusing. Robin Williamson’s sawing fiddle is a beautifully vague stylistically speaking (which was the point) but atmospheric as if straight out of Old Nick’s Fiddle Triangle – Cape Breton, Berkeley Old Time Fiddler’s Convention (immortalised on the Folkways’ album Berkeley Farms) and the Fake-Appalachians. Cultural thievery from two of the best. Chutzpah and a hoot to boot. “Now is the time to slip away from the California sun/To a place where a man can be as free as the wind” etc. From Wee Tam & The Big Huge (Fledg’ling FLED 3079, 2010)

Fledg’ling is at www.thebeesknees.com

Rishte Bante Hain – Asha Bhosle

Rahul Dev Burman composed the music: Gulzar wrote the lyrics: Asha Bhosle sang. Rishte Bante Hain means ‘Relationships Grow Slowly’. It is one of R.D. Burman’s most lilting melodies that he ever magicked out of his imagination. Even before factoring in its lyrical content, the magic is clear in the detail of the arrangement and is filigree touches. Finger-pop percussion, sarod and Ashaji‘s voice of sailing over everything, with only of a spot of multi-tracking as assistance. Eloquence on so many levels.

A song to go to the grave with. From Dil Padosi Hai (1987) available on The Rough Guide to Bollywood Legends: Asha Bhosle (RGNET 1131 CD, 2003)

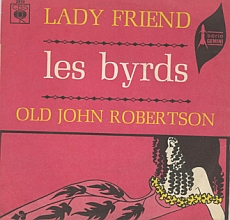

Lady Friend – Les Byrds

Lady Friend – Les Byrds

Mike Ledgerwood’s review on page 15 of the Disc and Music Echo of 2 September 1967 enthused, “The Byrds are back! With that crashing, full-blooded guitar sound and haunting voice harmony built around David Crosby’s ‘Lady Friend’ (CBS). A vast improvement on their recent offerings. Deserves to be a hit.” But who could afford Disc and Music Echo?

One baking hot summer’s afternoon in 1968 in a small town somewhere on the Cherbourg peninsula, the light was so bright it was dazzling. The French town was undergoing a collective siesta. All the cafés and bistros were as shut as an early-closing Sunday in Britain. In that small town whose name nobody will ever recall, a Francoise Hardy-inspired, aching-loined adolescent ducked into a little record shop that, in denial about sunshine and siesta, was stoically open and trading. It was like an oasis of life in a mirage of inertia without a diablo de menthe in sight. Adjusting his fetchingly blue eyes to the darkness whilst flicking through the picture-sleeved 45s, one caught his attention. It was Les Byrds.

Maybe it was the confidence of callow youth or just not knowing he was a junior polyglot in the making, but reading Les Byrds did not throw him. As somebody sang, life was much simpler then. One went into a record booth in some foreign country clutching a record and, 2:30 minutes later, maybe one emerged happier and francs and centimes lighter.

Lady Friend, with its welling harmonies, pounding drums, stabbing brass and chiming guitars, is one of those David Crosby songs that allegedly helped split the band. Supposedly, Triad, Crosby’s hymn to troilism – not a word heard much back in England – had proved too rich, too rum for Les Byrds (so Crosby got Jefferson Airplane to cover his beastliness) and Lady Friend probably sounded like a loose cannon going off. It never made an album but in that small corner of Cherbourg that lad located a treasure.

Three decades later he spoke to Crosby about that encounter. Crosby had no notion that the Lady Friend had ever be released in France – with or without a picture sleeve. “Man, that’s a collector’s item!” he laughed. From Les Byrds – Lady Friend b/w Old John Robertson (7-inch single, France, CBS Série Gemini 2910, undated and/or The Byrds (Columbia/Legacy C4K 46773, 1990)

Qushtar – Sirojiddin Juraev

A piece comparable to Davey Graham’s Anji for acoustic guitarists. Qushtar apparently means ‘double strings’. Juraev’s technique involves tuning strings in unison and fretting and plucking the dutar – the Uzbeki long-necked, fretted lute – at the same time. This is also combined with a tapping effect reminiscent of flamenco guitar. A tour-de-force. From Music of Central Asia Vol. 7 – In The Shrine of the Heart – Popular Classics from Bukhara and Beyond (Smithsonian Folkways SFW CD 40526, 2010)

Dhun in Misra Kirwani – Homayun Sakhi and Rahul Sharma

Dhun in Misra Kirwani – Homayun Sakhi and Rahul Sharma

In Hindustani music a dhun is a folk air or sometimes a piece played in a folk idiom. ‘Misra’ or ‘Mishra’ signifies ‘mixed’ and indicates that the composition does not follow strict râg rules. Kirwani is a South Indian râg that has gained great popularity in Northern Indian musical circles. However, Misra Kirwani is hardly a commonplace morsel. (Ali Akbar Khan released a 1985 recording of it on his In Concert at St. John’s, on which Zakir Hussain accompanied on tabla.) This rendition is an Afghani-Jammu-Kashmiri one. Sakhi plays the rubab – a kindred instrument to sarod – while Sharma plays the santoor, the instrument that his father, Shivkumar Sharma turned new worlds of music-lovers on to.

Sharma came up with the opening composition in Misra Kirwani, Sakhi followed suit and then they flew. This spontaneous composition’s variations are a one-off and the next time who knows where the next logical conclusion might lead them? This rendition is better than good enough for the present. From Music of Central Asia Vol. 9 – In The Footsteps of Babur – Musical Encounters from The Lands of the Mughals (Smithsonian Folkways SFW CD 40528, 2010)

Poslechněte, lidé – Jiři Kleňha

It is peculiar how people forget to stop assuming that things won’t change. Me included. We riff on life and forget to remember. Jiři Kleňha is somebody I associate with Prague. He was another of the street musicians that played on Charles Bridge but unlike the guitar-playing buskers and the jazz band he did something only found in Prague. Jiři’s pitch was at the Karlova, Old Town end of the bridge and he played a hammer chord zither called the Fischer’s Mandolinette. Apparently the instrument had been part of a family of chord zithers whose stronghold in the first decades of the twentieth century had been on the Saxony side of the German border and the Sudeten in Czechoslovakia. In German the instrument was also known delightfully as Fischer’s Lieblings-Klänge, meaning ‘Fischer’s Favourite Sounds’, though it has also been translated more freely as ‘Fischer’s Lovely Sounds’.

Over many’s the year, I stood and watched Jiři Kleňha play. He rarely played for more than a few minutes – two or three – at a time before invariably somebody would approach him and ask him about the unfamiliar instrument that he was playing. Down the years, admirers of his artistry had translated his giveaway sheet in Czech into various languages. He would courteously enquire where somebody came from before fishing out the appropriate variant of his leaflet from his bag. One early evening a few years back, I waltzed David Harrington of the Kronos Quartet across the bridge from the hilly castle side, hopeful that Kleňha would still be there. Getting closer, the bright ringing tones of the Fischer’s Mandolinette confirmed he was. Entranced, we stood and listened.

The longest piece of the 37 tracks on this Yuletide CD is under three minutes in length. Each is a miniature, an exquisite Czech miniature, a distillation of melody. The last time I was in Prague in September 2009, Kleňha wasn’t there the whole week. I do hope he was somewhere nice on holiday. The title track from Poslechněte, lidé (no number, 1995)

More information in Czech, Russian and English at www.aa.cz/citera

7 Seconds – Neneh Cherry and Youssou N’Dour

7 Seconds – Neneh Cherry and Youssou N’Dour

The weekend of 17-18 April 2010, as Werner Richard Heymann (1896-1961) wrote all those years ago, had to be a piece of heaven. In Whitton, Middlesex in any case. The skies were clear and blue. More betterer, thanks to the Icelandic volcanic eruptions at (the eminently copy-and-pastable and equally unpronounceable) Eyjafjallajökull, the skies were clear of planes over London until 21 April. Bliss. Sitting in the Admiral Nelson on a writing jag/break, Neneh Cherry’s 1994 record came on. As she and Youssou N’Dour sang, Whitton and the world became a still more harmonious, an even still more betterer place.

Co-credited to Cherry, N’Dour, Cameron McVey and Jonathan Sharp, 7 Seconds (though in my head until checking it was always 7 Seconds Away) appeared on N’Dour’s album The Guide (Wommat) and became the performance that didn’t really fit or sit comfortably on her solo album, Man. The spring sunshine, the drone of bees, the silence of hoverflies, a couple of days of listening to songbirds in the garden adjusting their volume controls not having to compete with the growl and revving back of incoming, Heathrow-bound planes, led to an epiphany or three. And 7 Seconds with its lyrics in Wolof, French and English became the theme song for a new springtime of peace and communication, however hippy that sounds.

7. 5. 2010 |

read more...

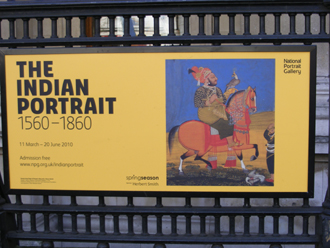

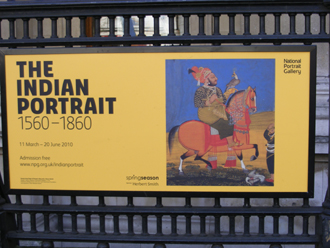

[by Ken Hunt, London] London’s National Portrait Gallery is currently offering two marvellous exhibitions of Indian art. Admission is free and while they may not appear to cast much light of the subcontinent’s musical arts, amid the huqqa smokers, the military figures, nobility and royalty, there are a few correlations between Indian portraiture and aspects of the subcontinent’s music to interest the musically minded.

[by Ken Hunt, London] London’s National Portrait Gallery is currently offering two marvellous exhibitions of Indian art. Admission is free and while they may not appear to cast much light of the subcontinent’s musical arts, amid the huqqa smokers, the military figures, nobility and royalty, there are a few correlations between Indian portraiture and aspects of the subcontinent’s music to interest the musically minded.

The Indian Portrait 1560-1860 draws on works from successive Mughal courts, from an era when patronage – sponsorship in the modern arts vernacular – was keen to log its movements in an era before photography. Amid the portraiture of personages and merchants from Rajasthan, Gwalior and elsewhere in poses with blade and blossom or the courtesans at leisure, three images stand out.

One entitled ‘The vina player Naubat Khan Kalawant’, in fact turns out to be unnamed on the portrait, although the exhibitors or art historians have deduced him probably to be Misri Singh, “a Rajasthani musicians at Akbar’s court who was given the title Naubat Khan” on the basis of him being in charge of the naubatkhani – from the context the gateway above which music was played. He is captured in a stylised setting of plants and small birds rather than any palatial or urban backdrop. His portrait is attributed to Mansur (cryptically “the work of the designer Mansur”) and dated to circa 1590-95. The image is fascinating. He appears to be playing the vina – the two gourds of which are brightly decorated in blue, crimson and gold – but not in the customary seated position as we became accustomed to seeing in the second half of the twentieth century. Instead he looks like a travelling bard and is depicted standing as musicians were later depicted in postcards from the first half of the twentieth century. In picture postcards of nautch (courtesan) entertainers, for example, sarangi players are often depicted standing with the instrument braced against a waist pouch. Interestingly, there appears to be a deliberate attempt to capture Naubat Khan Kalawant’s features as an individual, not as a cipher.

This is in contrast to the Rajasthani portrait called ‘A lady playing a tanpura’ from around 1735 “in ink, gold, opaque and transparent watercolour on paper”. She is unidentified, her features a cipher of the Indian Everywoman. The portrait is all the better for that. Her hair is long and cascades from beneath a bejewelled and pearled turban. She holds her five-stringed tanpura upright (only four tuning pegs are visible). This way she stands for generations of anonymous musicians or nautch entertainers whose features and names are long forgotten. It is on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fletcher Fund. It is a real find. It is available as a postcard.

This is in contrast to the Rajasthani portrait called ‘A lady playing a tanpura’ from around 1735 “in ink, gold, opaque and transparent watercolour on paper”. She is unidentified, her features a cipher of the Indian Everywoman. The portrait is all the better for that. Her hair is long and cascades from beneath a bejewelled and pearled turban. She holds her five-stringed tanpura upright (only four tuning pegs are visible). This way she stands for generations of anonymous musicians or nautch entertainers whose features and names are long forgotten. It is on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fletcher Fund. It is a real find. It is available as a postcard.

Her anonymity is in marked contrast to a portrait of courtesans shown off-duty, loaned from the San Diego Museum of Art, Edwin Binney 3rd Collection. ‘A group of courtesans’, stated to be from Delhi around 1820, depicts six recognisable individuals, perhaps even favourites, with different skin hues, different styles of clothing. The portrait is exquisite and in its detail it casts light on an aspect of culture. Until historical times, most musicians in the subcontinent were faceless. They might play for royalty, the elite and the moneyed but they ate with the servants.

More information at www.npg.org.uk/whatson/exhibitions/the-indian-portrait-1560-1860.php

7. 5. 2010 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Folk music everywhere goes through changes of style and presentation. Little is immune to change. That applies whether we are considering traditional or revivalist forms. After all, everything starts from somewhere before going somewhere else. Very little is fixed in a stone. The US folksinger Susan Reed, who died on 25 April 2010 in Long Island, New York State, had a relatively short-lived but important part to play in the East Coast folk scene of the second half of the 1940s into the 1950s.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Folk music everywhere goes through changes of style and presentation. Little is immune to change. That applies whether we are considering traditional or revivalist forms. After all, everything starts from somewhere before going somewhere else. Very little is fixed in a stone. The US folksinger Susan Reed, who died on 25 April 2010 in Long Island, New York State, had a relatively short-lived but important part to play in the East Coast folk scene of the second half of the 1940s into the 1950s.

Born Susan Catherine Reed in Columbia, South Carolina on 11 January 1926, she grew up in a theatrical family. Her father, Daniel was in the film industry while her mother, Isadora was a theatrical publicist. From an early age she and her brother Jared – three years her senior – imbibed folk music and folklore the way that many left-leaning families did but they also came into contact in person with the likes of folklorist Carl Sandburg, whose influential The American Songbag was published the year after her birth.

Susan Reed became a folksinger in the then-current American mode. She never had folksong in her blood like her later Elektra label stablemate Jean Ritchie of the Singing Ritchies of Kentucky, but was not the point. She was projecting something else, something more citified, whether she was singing American folksongs or Irish songs gleaned from members of Dublin’s Abbey Theatre Company. By the time she gave her major public debut at NYC’s Town Hall in 1946, she had several years of experience when it came to singing in public in clubs, churches and, like Austria’s Trude Mally, for the war-wounded.

She recorded a flurry of albums, including Folk Songs for Columbia Masterworks (a 12-inch album on the other side of which were 7 Songs of the Auvergne taken from Joseph Canteloube) and I Know My Love for RCA Victor. She also became an early member of the Elektra roster alongside Jean Ritchie, Ed McCurdy, Cynthia Gooding, Oscar Brand and their kind – a prelude to its folk explosion in the early to mid Sixties with Judy Collins, Tim Buckley and their kind. Jac Holzman bows to bollocks (cliché) and calls her “an art singer with a silky voice kissed by Irish mist” in Follow Me Down – The Life and High Times of Elektra Records in the Great Years of American Pop Culture (1998).

As folk became a four-letter word in the 1950s, she came under scrutiny of the US authorities and, like Pete Seeger and the Weavers, found herself blacklisted. These events coincided with her style of folk music losing its popularity. Increasingly, she was relegated, like Richard Dyer-Bennet and John Jacob Niles to a folk hinterland, once the new wave of ‘more authentic’ performers blew into town and onto the airwaves. If only they had been of the calibre of Jean Ritchie! When the bubble burst, Susan Reed did other singing and moved on. She also ran an antique shop in Nyack, NY.

But the next time you hear or sing Black Is The Colo(u)r, Go (A)’Way From My Window, If I Had A Ribbon Bow, (S)He Moved Through The Fair or Must I Go Bound, remember others went before.

7. 5. 2010 |

read more...

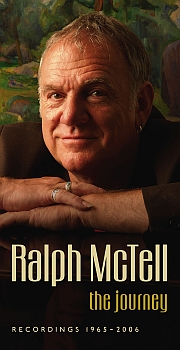

[by Ken Hunt, London] Ralph McTell is one of Britain’s foremost commentators on the national condition using demotic idioms – folk, blues, ragtime. Rather like Wolf Biermann, Franz-Josef Degenhardt and Christof Stählin in Germany (and then add your own regional or national candidates), he has depicted his homeland through music, through songs, that meanings of which seem immediately apparent but which may well prove to be more eely or oblique.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Ralph McTell is one of Britain’s foremost commentators on the national condition using demotic idioms – folk, blues, ragtime. Rather like Wolf Biermann, Franz-Josef Degenhardt and Christof Stählin in Germany (and then add your own regional or national candidates), he has depicted his homeland through music, through songs, that meanings of which seem immediately apparent but which may well prove to be more eely or oblique.

This snippet is drawn from a long interview conducted in September 2006 for an article that appeared at the time of the release of the self-effacing man’s 4-CD boxed set, The Journey – Recordings 1965-2006 (Leola OLABOX60) that David Suff put together for the label.

True to his roots, McTell booked a folk club gig at Twickfolk @ the Cabbage Patch Pub in Twickenham, Middlesex in March 2010, prompting this morsel.

What did you learn about your own creative process from The Journey?

Very good question. I think we have to go back to my perceived role for myself. I think that it is not a keeper of the scrolls or the tradition, or a protector of the tradition; it is the belief that there is a basic honesty in one man and a guitar if the subject matter is right. My stimulus is drawn from men and women who appeared to do that for me. All, I think, I sought to do while I was doing that, was to get better at what I was doing. Which is partly to enjoy and to discover the music myself and to exploit what little I have or what my offering could be and to try to improve. But not to lose sight entirely of what first motivated me. The odd excursion I have made into a broader folk-rock field or whatever was all done with the same intent. The idea of doing songs in the main still had to fit those criteria.

Listening back [to The Journey], it’s not as good as what I hoped at the time. Considering I’m a very bad recording artist. I’ve had a 40-year career, sometimes I say in spite of my recordings! I’m not at ease in the studio. I don’t like recording studios. I don’t enjoy recording and I don’t particularly enjoy listening to my own records. But I enjoy the process of creating. I leave the ‘studio bits’ to other people. I have managed to develop the rather useless talent of hearing what I want to hear when I’m listening to playback. I’m not as hard enough on myself, on mixes and on performances as I should be.

When I was working with a producer like Gus Dudgeon who sought perfection at every level, he must have despaired of me. We parted company on the basis that I couldn’t keep repeating performances. Since I have liberated myself from that by doing only live vocals and only one or two takes I’m much happier with those recordings that have gone back to the basic honesty of those first recordings by other people that I love.

So, that’s what I’ve learnt. I’ve learnt, one, that there’s nothing wrong with the odd foible, dodgy note, slightly sharp, breathless, more moved than moving – as my manager once said to me – and gone for the way Bob [Dylan] does it. I’m not blessed with a voice that can soar and rise and do the things that Bob can do in his individual performances, but my voice has grown, has got broader, wider, deeper, whatever. I’m as sincere as I ever was. I trust my 40 years of guitar playing and singing to get a reasonable performance down in the studio.

But to say I’m a fan of my own records is not true. I can be delighted with other people’s performances but they’re very wordy songs, so I don’t often give a lot of room for other people to blow or to play over. They’re there to enhance the song and to fill out what I hear in my head within the chord structure that I’ve created.

How do you feel about your personal progress? For instance, you have a song on the boxed set to do with your wife, Nanna. You have a very early recording of Nanna’s Song [from Eight Frames A Second, 1968] and you have a much later one [from Travelling Man, 1999] which is a much simpler version of Nanna’s Song. Is that going back to what you’ve just said about the basic honesty of a man and guitar and a voice?

Yes, I think it is. When I wrote that song I wrote it how you hear it the second time. When I took it to the studio, they went, ‘Oh God, it’s French! We’ve got to put some accordion on it.’ It was all a kind of musical cliché. Actually that song on that first album probably sold the album. Because I think it was an honest intent. If someone were to study that song I hope they would see it’s not just a song of being in love in Paris. It’s a song of regret that things are coming to a close – though they never did. But that’s the perception of the song at the time. It’s a wistful song that deals with meeting and parting somehow. Are they still together? Do you know what happened?

I’ve got this thing about songs. If you get it straightaway, it’s one kind of song; if it creeps into you, it’s another song; if you return to a song, it’s another. I picked a quote up the other day from Samuel Taylor Coleridge: it’s the poems we go back to, to read again that are the special ones. I would like my songs to be thought of like that. I would like it would be possible to go back to them and find something that you didn’t get the first time.

The exception to that is the ‘big song’ – The Streets of London. It is what it is: it does what it says on the tin: there’s no need to go back to it. And ironically it’s the one that everybody goes back to and keeps talking about. That’s the way it is. Most of my songs aren’t as direct or as straight ahead as that. I like to think there’s nearly always a built-in ‘something else’.

Small print

Unless otherwise stated, all interview material is original and copyright Ken Hunt. If you wish to quote, seek permission. It’s the writer’s way.

For more information and updates about Ralph McTell, go to www.ralphmctell.co.uk

2. 4. 2010 |

read more...

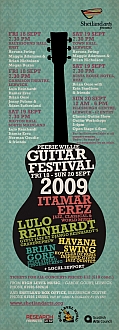

[by Ken Hunt, London] April and another month in music rolls around and brings ten snapshots of what got played oodles. This divine bumper pack of GDDs comes courtesy of Broadlahn, David Lindley & Wally Ingram, Fred Astaire, Reem Kelani, Rajan Spolia, the Grateful Dead, Bonnie Dobson, Peerie Willie Johnson, Abida Parveen and Mac Rebennack.

Bua von Muata Natur – Broadlahn

Bua von Muata Natur – Broadlahn

The Graz-based Austrian folk fusion group Broadlahn was founded in 1982 and took their name from the dialect word Broadlahn which means a wide avalanche as well as being the name of an area of alpine pasture in Austria’s Upper Styria region. Bua von Muata Natur is a setting of the Beatles’ song Mother Nature’s Son from Broadlahn’s first album. (Bua is a southern idiom for son or boy.)

It opens with the sound of metal being whetted as a rhythm track. Scythe rhythm is a trick worthy of Tom Waits – and nifty trick enough for that wonderful Bavarian folk-punk band Hundsbuam (meaning the mildly pejorative ‘Dog Boys’ or ‘Sons of Curs’) to have employed it too. Broadlahn’s setting of the lyrics works really well and the performance really brings out the melody’s charms. I happened to be planting raspberry canes and Broadlahn’s version of the Lennon/McCartney song from The White Album sprang into my mind and kept popping up the whole month like a rabbit after my tasties. From Broadlahn (The Fab Records 1990 (GDCD 4009, 1993)

More information about Broadlahn at www.broadlahn.at

When A Guy Gets Boobs – David Lindley y Wally Ingram

In simple statements are great truths revealed. This paean to male sagginess begins with a mellow, flowing introduction that could go in any number of directions. The direction it goes in is John Lee Hooker-wards, though that vibe only really kicks in once Lindley finishes his taxim-like overture and starts singing about Mr Puffy’s expanding set of new glories.

The song even has a Homer Simpson-esque ‘renunciation’ of fattening foodstuffs that in the spirit of Homer you just know will never happen. Maybe it was the product of Stilton, water biscuits and port before climbing the wooden hill to Bedfordshire. Maybe it was brought on by thinking about Bollywood playback, Lisbeth Scott and Avatar, followed by the UK film critic Mark Kermode’s rebranding Avatar as Dances With Smurfs. But in a hypnagogic state I dreamed a dream of David Lindley singing When A Guy Gets Boobs in Springfield and the world was a happier place.

A plea to Mr Groening. If there were any justice in the world a canary-coloured Lindley will guest in The Simpsons singing When A Guy Gets Boobs. From Live In Europe! (No label name, no number, 2004) available from www.davidlindley.com

Let’s Face The Music And Dance – Fred Astaire

Fred Astaire (1899-1987) is a much underestimated singer. His top hat, tails and cane unfairly overshadowed his vocal prowess in his lifetime. He delivers Let’s Face The Music And Dance from the 1936 RKO picture Follow the Fleet with great nuance, style and glamour. It’s one of those songs, the lyrics of which define a time and are also timeless. Came the war, those lyrics came freighted with additional meaning. That is the timelessness of Irving Berlin’s song. I heard the song on the BBC. It lodged and stayed and as it wasn’t on the Fred Astaire anthology that I have you get no discographical recommendation.

Yafa! – Reem Kelani

Before The Last Chance, an anthology of eight songs about Israel and Palestine” on themes of Shoah and Nakbah – the ‘Holocaust’ and ‘Catastrophe’ of Jew and Palestinian – I regret to say that the Palestinian singer, musician and broadcaster, Reem Kelani’s music had passed me by. As had her name. It also appears in some places as Riim Yusuf Kilani.

Yafa! (‘Jaffa!’ as in the ancient port) is her setting of words by the poet Mahmoud Salim al-Hout (1917-1998). It is a threnody for a bygone time in the city of the title, in a place that seems as if it was a paradise in comparison with the Hell it is now.

Zoe Rahman’s piano accompaniment is languid and brooding. The pairing of voice and piano is powerful stuff. The track originally appeared on Reem Kelani’s Sprinting Gazelle – Palestinian Songs from the Motherland and the Diaspora. From The Last Chance (Fuse Records CFCD 008, 2010)

For more information, see www.reemkelani.com

It’s Still Raining – Rajan Spolia

This is the Punjab-born, British-based guitarist Rajan Spolia at his inspiring best. He lists it as a Nash/Goffin/King composition. However, it is more in the spirit of a ragamala – a ‘garland of ragas’ – than a medley. Spolia conjures ‘I Can See Clearly Now’ out of some Beatle-esque phrasing. But that is just part of this marvellous piece of music. The man is long overdue wider recognition. The sheer invention and fluidity of his playing is remarkable. From More Than Words: Snake Music (Chapter IV) (Hard World HWCD008, 2010)

Go to www.rajanspolia.co.uk for more information

Dark Star/El Paso/Dark Star – Grateful Dead

In November 1971 the Grateful Dead arrived at the Municipal Auditorium and Convention Center in Austin, Texas. The band was in a process of regeneration, thanks to the recruitment of their new keyboardist Keith Godchaux. The other players were Jerry Garcia on lead electric guitar and vocals, Bill Kreutzman on kit drums, Phil Lesh on electric bass guitar and vocals and Bob Weir on rhythm guitar and vocals. (Ron ‘Pigpen’ McKernan was increasingly out of action and recruiting another keyboardist was a far-sighted move.) Godchaux had learned the core repertoire from the vantage point of an admirer of the band’s music. This recording of the band’s signature space anthem, recorded by Rex Jackson, finds Godchaux straining at the leash, egging the band on with piano filigrees and fills.

Ten minutes or so into the performance, Weir suggests, feints or cues them into a segue and a couple of minutes later they slide into Marty Robbins’ cowboy-film-in-song El Paso. A masterful transition. Weir sings his cowboy song, visits the cantina, does his business, doffs his Stetson, gets shot (“dreadfully wrong”) and within five minutes, Garcia and Lesh remind the band that they are back in modern-day Texas. They return to Dark Star space via a worm hole through atonalism and jor-like, unmetered rhythmicality before breaking out of the ‘darkness’ into the full glare of what they call Dark Star here but which is more like uncharted space. From Road Trips – Austin 11.15.71 (Grateful Dead Productions GRA2-6014, 2010)

Stay With Me Tonight – Bonnie Dobson

Bonnie Dobson recorded this female take on the Stones’ Let’s Spend The Night Together in 1983. Annie Graham, Gerry Hale and Richard Lee of Telephone Bill and The Smooth Operators accompany her on this archival recording that had vanished until now. She is sassy and inviting and a great little character actress on this one. From Looking Back (Biber 76831, 2010)

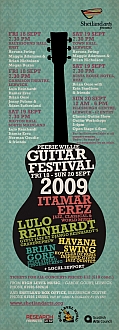

Margaret’s Waltz – Aly Bain and Peerie Willie Johnson

‘Peerie’ Willie Johnson (1927-2007) was a Shetland-based guitarist who thanks to the curvature of the globe – and the absence of land masses – was able to enjoy faraway radio stations on the other side of the Atlantic. How strange is geography! Certainly, far stranger than geography teachers ever taught me. Still stranger, Johnson was posted to the main Royal Air Force base on the Shetland Islands soon into the Second World War. That was where my bandsman father was posted as the full-time (as in, excused any form of military activity whatsoever) clarinettist, saxophonist and arranger for the base’s dance band. Apparently Johnson used to sit in with the band. If he did he must have sat in with my father.

‘Peerie’ Willie Johnson (1927-2007) was a Shetland-based guitarist who thanks to the curvature of the globe – and the absence of land masses – was able to enjoy faraway radio stations on the other side of the Atlantic. How strange is geography! Certainly, far stranger than geography teachers ever taught me. Still stranger, Johnson was posted to the main Royal Air Force base on the Shetland Islands soon into the Second World War. That was where my bandsman father was posted as the full-time (as in, excused any form of military activity whatsoever) clarinettist, saxophonist and arranger for the base’s dance band. Apparently Johnson used to sit in with the band. If he did he must have sat in with my father.

I wrote Peerie Willie Johnson’s obituary in The Guardian and I am writing his entry for a Supplement for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. That is why I have been cramming his music again. This sweet fiddle and guitar waltz, originally on Aly Bain’s The First Album, does not capture the fire of Peerie Willie Johnson. It captures the smoulder. It reminds me of the tale told about Jean Ritchie and Doc Watson. Doc Watson, one of the all-time greats of guitar, hadn’t cut loose when accompanying her. She was puzzled. He told her that he had played what was necessary. That is what happens here. By the way, since you have been so patient and haven’t asked, ‘peerie’ is a Scots idiom for ‘small’, ‘little’. Like ‘wee’. His tradition lives on. From Willie’s World (Greentrax CDTRX309, 2007)

Isho Jannat Zameen Te Le Aaya Ae – Abida Parveen

A good friend turned me on to this album by the Sindhi Pakistani Sufi singer Abida Parveen, presented by the poet-lyricist Gulzar. Based on Punjabi folklore, the star-crossed tale of Heer and Ranjha attributed to Waris Shah unfolds. The meeting is a fortuitous one.

“Kohl [a darkening cosmetic] lines the top of her eyelids

Like Punjab sits atop Hind [India]

Those eyebrows arch arrow-straight

Like words line the sheaf of books.”

The accompaniments blend ancient and modern. The sound palette for Isho Jannat Zameen Te Le Aaya Ae includes bansuri (bamboo flute), rebab (short-necked fretless lute), dholak (double-headed barrel drum) and tabla, electric bass guitar and keyboards. What really, truly sings out is Abida Parveen’s voice. From Heer By Abida (Times Music TDIGH 016C, 2004)

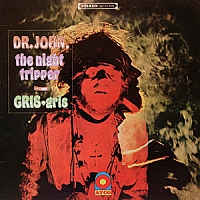

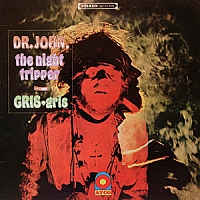

I Walk On Guilded Splinters – Dr. John

The Last Song you hear tonight should be this one. I Walk On Guilded Splinters – that is the way they spell ‘gilded’ on this anthology, topping ambiguity with ambiguity – originally appeared on Dr. John’s album Gris-gris in 1968. The vibe, the winds, the beats and the backing voices cook up something very deep and slightly disturbing. You do not have to know what Mac Rebennack is singing about or the ingredients he is throwing into the cauldron to intuit that he has been places you never will see or possibly never will want to see. From The Dr. John Anthology – Mos’ Scocious (Rhino 8122-71450-2, 1993)

The Last Song you hear tonight should be this one. I Walk On Guilded Splinters – that is the way they spell ‘gilded’ on this anthology, topping ambiguity with ambiguity – originally appeared on Dr. John’s album Gris-gris in 1968. The vibe, the winds, the beats and the backing voices cook up something very deep and slightly disturbing. You do not have to know what Mac Rebennack is singing about or the ingredients he is throwing into the cauldron to intuit that he has been places you never will see or possibly never will want to see. From The Dr. John Anthology – Mos’ Scocious (Rhino 8122-71450-2, 1993)

2. 4. 2010 |

read more...

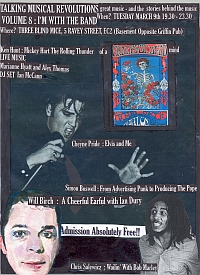

[by Ken Hunt, London] March’s stuff and nonsense comes from Mickey Hart and chums, Joni Mitchell, The Carolina Chocolate Drops, Bob Bralove and Henry Kaiser, Wajahat Khan and the Medici String Quartet, The Six and Seven-Eights String Band, Jo Ann Kelly, Dillard & Clark, Farida Khanum and Sohan Nath ‘Sapera’.

[by Ken Hunt, London] March’s stuff and nonsense comes from Mickey Hart and chums, Joni Mitchell, The Carolina Chocolate Drops, Bob Bralove and Henry Kaiser, Wajahat Khan and the Medici String Quartet, The Six and Seven-Eights String Band, Jo Ann Kelly, Dillard & Clark, Farida Khanum and Sohan Nath ‘Sapera’.

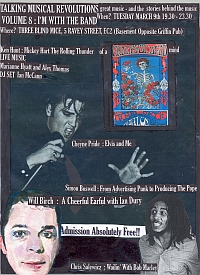

Rolling Thunder/Shoshone Invocation into The Main Ten (Playing In The Band) – Mickey Hart

In 1972 I clapped eyes on Kelley/Mouse’s Rolling Thunder cover artwork in a record rack in the tiny Virgin record store at Notting Hill Gate. It shone out that in some way it was Grateful Dead-related. It turned out that it was the Dead’s absentee drummer Mickey Hart’s solo debut. The opening track sequence draws on and draws in so many threads. Shoshone shaman Rolling Thunder, marimbas from Mike and Nancy Hinton, tabla from Alla Rakha and Zakir Hussain, the whole Calif rock caboodle participating on The Main Ten – John Cipollina and Bob Weir on electric guitars, Stephen Stills on electric bass guitar, Hart on drums, Carmelo Garcia on timbales and the Tower Of Power Horns. That’s why I opted to talk on the subject of Mickey Hart when my fellow writer friend Gavin Martin invited me to talk about anything I wanted at Talking Musical Revolutions 8. From Rolling Thunder (GDCD 4009, 1972)

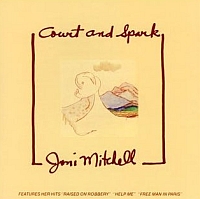

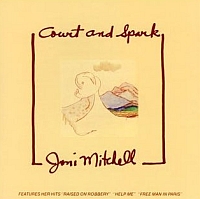

Help Me – Joni Mitchell

A long-running email dialogue with a rather special vocalist planted Help Me in my head and then the song kept rattling around. Potentially, Help Me is ghazal-like in its layered ambiguity. On hearing Help Me at the time of its release, it had seemed very much a woman’s song. Then under the influence of Iqbal Bano and Farida Khanum and a nazm here and a ghazal there, I got to thinking about how gloriously open to re-interpretation Help Me could be, once going beyond the tale of one of Joni Mitchell’s romances that failed to work out. And more importantly, how it might be twisted to reveal new facets and ambiguities with a further turn or two.

A long-running email dialogue with a rather special vocalist planted Help Me in my head and then the song kept rattling around. Potentially, Help Me is ghazal-like in its layered ambiguity. On hearing Help Me at the time of its release, it had seemed very much a woman’s song. Then under the influence of Iqbal Bano and Farida Khanum and a nazm here and a ghazal there, I got to thinking about how gloriously open to re-interpretation Help Me could be, once going beyond the tale of one of Joni Mitchell’s romances that failed to work out. And more importantly, how it might be twisted to reveal new facets and ambiguities with a further turn or two.

The arrangement begins with trademark Mitchell guitar chords (those tunings that always caused a double-take or two) before the band storms in. Her voice on this recording is as smooth as a silken scarf being run through a gold ring. As songs go, it is both as sheer as silk and barbed. As Help Me exits in one channel, in comes Free Man In Paris (another fine song) in the other. One day Joni Mitchell’s Asylum-era is going to get the treatment and sound it deserves. (What is it with the CD’s flat, gated (?) drum sound?) From one of her greatest works Court & Spark (Asylum 7559-60593-2, 1974)

Snowden’s Jig (Genuine Negro Jig) – Carolina Chocolate Drops

It’s always gratifying for the year to start with a humdinger of a concert that really sets the bar high. The Carolina Chocolate Drops did that with their Bush Hall, Shepherds Bush, London at the beginning of February 2010. I was born with two-left feet but when I hear something like Snowden’s Jig I really do wish for some sort of painless transplant that would enable me to do the soft-shoe shuffle. From Genuine Negro Jig (Nonesuch 7559-79839-8, 2010)

Red Queen – Bob Bralove and Henry Kaiser

During his tenure with the Grateful Dead until they folded their hand following Jerry Garcia’s death in 1995, keyboardist-composer Bob Bralove’s role gradually evolved. He and guitarist Henry Kaiser have taken as their starting points on this album an assortment of improvisations that Bralove fashioned in Grateful Dead concerts.

Explaining the project for this here website, Bralove lifts the latch to say, “Ultraviolet Licorice was a recording that was inspired by the back-up material I did for the drums and space parts of GD shows. By the end of the GD I was playing tracks and playing live as segues between drums and space. I recorded all of those performances isolated from the band. I could record just what I was playing to inspire the band to improvise. Henry and I looked at that material which was recorded during the last six years of GD shows and said, ‘Why don’t we use this to inspire us?’ So we went into Fantasy Studios in Berkeley, CA in July of 2008, dropped all of those recordings onto the multi-track and recorded live to them. On that session I played acoustic piano (Steinway Concert Grand) and Henry played electric and acoustic guitars. It was a one day session and a wonderful time.”

Red Queen differs from much of the material on Ultraviolet Licorice. It could almost be a throw-back to Paul Kantner’s Blows Against The Empire. At 2:28, it is the shortest piece on the album and therefore closer in length to Bralove’s Quicksilver Rain, Wind Before The Storm, Urban Twilight and the Bralove/Tom Constanten composition Cowboy Sunset on Bralove’s solo piano album, the delightful Stories in Black and White (BLove 1001, 2007).

Today, the Red Queen conjured in my mind is the Red Queen of Through The Looking-Glass. Tomorrow, she may be a character in a card game. The day after that, who knows? From Ultraviolet Licorice (BLove no number, 2009)

For more information about its participants go to http://bobbralove.com/music.html and http://www.henrykaiser.net/

Raag Desh – Quintet for Sarod and String Quartet – Wajahat Khan and the Medici String Quartet

Desh, also known as Des, is a late evening raga. It is very popular, it is much performed and, personally speaking, it is one of my favourites for the vistas it opens up. The sarodist Wajahat Khan, one of maestro Imrat Khan’s sons, places Desh (it means ‘country’ twinned with ‘homeland’) in a very different landscape to the ones that most interpreters have placed it in. The reason for that is simple: Paul Robertson (violin), Stephen Morris (violin), Ivo-Jan van der Werff (viola) and Anthony Lewis (cello). Collectively, the Medici Quartet. There is such sensitivity apparent here. Khan breaks the performance into four movements: Prayers of Love, Monsoon Memories, Romantic Journey and Celebration. The effect is pastoral and elevates the suite to amongst the highest achievements in East-West classical collaboration. From Wajahat Khan and the Medici String Quartet (Koch 3-6996-2, 2000)

Clarinet Marmalade – The Six and Seven-Eights String Band

The Carolina Chocolate Drops’s gig jolted me into revisiting my past. I thank them for that. The Six and Seven-Eights String Band of New Orleans, though from a parallel tradition to the one the Drops are exploring so ably, could be their godfathers. They are probably more or less forgotten now. More’s the pity. Apparently string band jazz was popular around 1910-1925 in New Orleans but little of it was ever recorded. The Six and Seven-Eights date from that era. They were long gone when that marvellous mandolin maestro David Grisman alerted me to the existence of their solitary Folkways album. Like Dave Apollon, they became part of my back-education.

There is a total joie de vivre – surely the right expression for a New Orleans-based band of such character – to their music. Credits: William Kleppinger (mandolin), Frank ‘Red’ Mackie (string bass), Bernie Shields (steel guitar), Dr. Edmond Souchon (guitar); produced by Frederic Ramsey Jnr and Samuel Barclay Charters. Smithsonian Folkways will do you a copy as part of the archival service. From The Six and Seven-Eights String Band of New Orleans (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings FA 2671, 1956)

The downloadable liner notes are at: http://media.smithsonianfolkways.org/liner_notes/folkways/FW02671.pdf

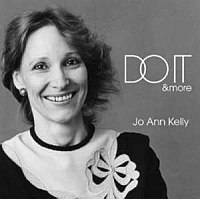

Black Rat Swing – Jo Ann Kelly

It is strange how things can happen. Jo Ann Kelly (1944-1990) was, to my mind, the finest and most natural female blues artist that England ever produced. Her self-titled Epic album was reviewed in one of the first issues of Rolling Stone that I ever saw. She was somebody I would have loved to have interviewed and learned from. We never talked to each other. The irony was that we were frequently tens of yards apart during our lives.

It is strange how things can happen. Jo Ann Kelly (1944-1990) was, to my mind, the finest and most natural female blues artist that England ever produced. Her self-titled Epic album was reviewed in one of the first issues of Rolling Stone that I ever saw. She was somebody I would have loved to have interviewed and learned from. We never talked to each other. The irony was that we were frequently tens of yards apart during our lives.

After she died in October 1990 there was a bash to commemorate her in a pub – the Royal Oak maybe – close to Clapham North tube station in London. The following Sunday I visited my parents in Mitcham on the north Surrey-south London border. As usual, I relayed what I had been up to and mentioned reviewing a musical wake for Folk Roots for a blues singer who had died way too early called Jo Ann Kelly. My mother commented that one of her neighbours five or so doors down had also been called Jo Ann, had been a musician and that she too had died recently. My mother continued that Jo Ann’s partner was called Pete Emery and talked about Jo Ann cycling off with her daughter on the ‘dickey seat’ – a Hunt family joke from my mother’s family’s Singer car’s pannier seat days (sorry about the Saxon genitive mouthful) – of her bicycle, taking her to school. At that point we realised that we were talking about the same person, doors down on the street that I had left two decades before. Never managed to find Pete Emery in afterwards when I knocked. Then when my mother’s illness caused me to move back in, events overtook. It never happened then either.

One of the people I met at Jo Ann’s farewell bash was John Pilgrim, master of the Viper-ish washboard, whip-speed anecdote and quip alike. If I could bottle Pilgro’s recollections and finagle a monopoly on incontinence pads, I would be a very rich man. John plays washboard on Black Rat Swing, a Soho pick-up (honest, it’s a great story) and pre-Pentangle Mike Piggot plays fiddle, the lass sings and Pete bubbles away on electric guitar. It is an epitome of groove. From Do It & more (Hatman 2023, 2008)

www.manhatonrecords.com

The Radio Song – Dillard & Clark

Dillard & Clark – Doug Dillard and Gene Clark – were an act that never achieved their full potential yet what they delivered on their two albums – The Fantastic Expedition of Dillard & Clark (1968) and Through The Morning, Through The Night (1969) – was truly spectacular. The warmth of the harmonies and the strength of the musical support conjure glowing memories. The Radio Song is a performance that I associate with a visit to Collett’s in New Oxford Street at the time of the album’s UK release. Hans Fried – who, with Gill Cook, was one of the lurking presences in that record shop – and I got stuck into good-natured banter about Dillard & Clark and the Flying Burrito Brothers.

The interwoven strands of Dillard & Clark’s voices, the chop-chord and burbling mandolin, steady rhythm guitar and the sly introduction of bowed string bass create the sort of combination you can spend hours – and years – unpicking. From The Fantastic Expedition of Dillard & Clark/Through The Morning, Through The Night (Mobility Fidelity Sound Lab MFCD 791, undated)

Read more about Dillard & Clark at Crawdaddy!‘s online presence:

http://www.crawdaddy.com/index.php/2010/02/02/the-fantastic-expedition-of-dillard-and-clark/?utm_source=NL&utm_medium=email&utm_ca mpaign=100209

Bale Bale – Farida Khanum

Farida Khanum is a Punjabi treasure. That assessment should apply to both sides of the Wagah Border. Regrettably, there is a really unfortunate snootiness on the border’s Indian side towards Pakistan-based artists. This is a piece of Punjabi tradition, praising the gait of Punjabi womankind. Talking the walk, if you prefer. “Bale Bale” – maybe “bole bole” comes closer for Anglophone ears – means, “Say, say”, “Tell, tell”, that sort of thing in the scheme of Punjabi-ness. No doubt there are better recordings of her doing this staple in her repertoire but I really do not care one iota. Don’t be put off by the la-la-la introduction.

There is an ambience and presence to this recording (and her other seven performances on it) that distils so much. This version, the (untranslated) French notes state, comes from the film Pardesi (‘Stranger’ or ‘Foreigner’) after an idea by Martina Catella. It’s a simple song with harmonium, hand-drum and handclap accompaniment. In its simplicity it says so much about the Punjabi character and the perils of division. It’s a very optimistic song. From Pakistan – Musiques du Pendjab, Vol. 2 – “Le Ghazal” (Arion ARN 64301, 1995)

Phagan Ka Lehra – Sohan Nath ‘Sapera’

I should apologise for this choice but I’m jolly well not going to. Advance copies of my Rough Guide to India arrived and, like one does, I played it. This piece of Punjabi folk music taps into Ludhiana’s Rajasthani migrant worker influx – think Mexican bracero field workers at whatever picking time in California in particular to get a US parallel – and consequential cultural cross-fertilisation.

I should apologise for this choice but I’m jolly well not going to. Advance copies of my Rough Guide to India arrived and, like one does, I played it. This piece of Punjabi folk music taps into Ludhiana’s Rajasthani migrant worker influx – think Mexican bracero field workers at whatever picking time in California in particular to get a US parallel – and consequential cultural cross-fertilisation.

Shefali Bhushan’s Beat of India from which this snake-charmer music derives is one of the truly great labels promoting India’s folk arts. If there is one more active when it comes to promoting India’s folk music, pray tell. This is music with dirt under its nails, not folkloristic park entertainment or ‘gentrified’ folklore. From The Rough Guide to the music of India (World Music Network RGNET1231CD, 2010)

Context from Aparna Banerji at http://www.tribuneindia.com/2010/20100117/spectrum/book6.htm

11. 3. 2010 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] This month’s prime quality stuff offers up some seriously magnificent music. This time round on the Banquet Isle with the hole in the middle, Joseph Spence and the Pinder Family, Steeleye Span, Emily Portman, Chumbawamba, Jenny Crook and Henry Sears, Eddi Reader, Lennie Tristano, Kate & Anna McGarrigle, Incredible String Band and KK are serving up the goodies.

I Bid You Goodnight – Joseph Spence and the Pinder Family

I Bid You Goodnight – Joseph Spence and the Pinder Family

Manumission is a ‘big’ word in several senses. It means a release from slavery. (The Shorter Oxford Dictionary finesses its meaning better if more wordily.) The day I first heard I Bid You Goodnight, a piece of musical magnificence if ever, upstairs in Collet’s folk department in New Oxford Street in London was a day my life changed forever. It was nothing less than a musical manumission. That Nonesuch album, The Real Bahamas, was mind-blowing.

I Bid You Goodnight was more blues, more gospel than I had ever heard from anyone in my life. The weaving voices were revelatory, a similar sort of impossibility to The Watersons. It was the stuff of dreams that necessitates re-calibrating and re-tuning your ears. (All the while delighting in so doing.) I Bid You Goodnight is a performance that needs repeated doses – not to get the gist of, but to imbibe over and over the better to appreciate it.

Later, I met Jody Stecher and Peter Siegel who had recorded Joseph Spence and the Pinder Family in the Bahamas in 1965 for that Nonesuch LP. (The credits were misspelled ‘Pindar’ on the original vinyl Polydor Special edition of the LP that I tracked down in Woolworth’s at Tooting Broadway for twenty-five pence, as they had been on the US Nonesuch edition.) Still later, Peter took me and my daughter to the exact spot near the Brooklyn Bridge where he had taken Joseph Spence. A hallowed place, one might say.

When I interviewed Jody Stecher, he told me about a second take of I Bid You Goodnight that had never been issued because of a glitch because of people pressing in too close to the microphone. That second version, the one here, now cleaned up, eventually appeared in 1992. It differs from the Nonesuch ‘original’ the way folk music should differ. (If you want something pretty much replicated exactly from performance to performance, opt for the Eagles.) For Giant Donut Discs I am taking the Rounder version.

For reasons of the heart, mind and body, the Nonesuch version, however, would be one of my all-time Desert Island Discs. From The Spring of Sixty-Five (Rounder CD 2114, 1992)

Who’s The Fool Now? – Steeleye Span

Around 1968-69 I seem to remember hearing this song sung by The Home Brew (Michael Clifton, John Fordham and Ray Worman) on the wireless. Maybe I’m conflating events but in my memory the session also had Shirley Collins singing. I placed plastic against Bakelite and recorded the broadcast on a Phillips open-reel. I have no idea what happened to that tape but Steeleye Span’s rendition brought memories flooding back.

The song is a lustrous commentary on the state of inebriation – or altered states. Or maybe merely an observation on absurdity and a world in which a hare chases a hound, a mouse chases a cat, cheese eats a rat and so on. It opens disc one of the CD and DVD. From Live at a distance (Park Records PRKCD104, 2009)

More information at: www.parkrecords.com

Fine Silica – Emily Portman

Emily Portman’s reaching for notes on Fine Silica evokes in me memories of Annie Briggs and Lal Waterson. Exquisite. From The Glamoury (Furrow Records FUR002, 2010)

More information at: www.emilyportman.co.uk

Pickle – Chumbawamba

Pickle – Chumbawamba

I was writing some lines about the first time I heard Anne Briggs’ Hazards of Love in a record shop and the way the information on the back of an LP or an EP was a whole world of information to be lapped up in those pre-internet days. The following day Chumbawamba’s newie landed on the doorstep and rather than plopping ABCDEFG on the digital Dansette and listening to it, I deliberately took the package down the Nelson to read the notes before playing the CD. Much as I had done with Hazards of Love back when.

Loads of the stories in the notes were ones I knew but I’d never seen them assembled in such wantonly redolent order. Reading them felt like it used to do when one was spinning the dial on the radio and slipping and sliding between domestic radio stations, static and faraway signals. The tales embrace Brecht, Metallica, the Devil’s Interval and Shostakovich. Good company, eh?

Pickle is inspired by a retort of Martin Simpson’s about “people who want to keep music faithfully traditional, want to preserve it and not alter it.” Martin’s reply: “That’s not music” – pause – “that’s a pickle.”

Coda. Since these are my donuts, the Chumbas’ Hammer, Stirrup & Anvil about Shostakovich’s ear and what we get to hear gets shoehorned in here as a Bonus Donut. From ABCDEFG (No Masters NMCD33 and Westpark WP87186, 2010)

More information at: www.chumba.com

Kwela Ceilidh – Jenny Crook and Henry Sears

Certain things do not transplant well. The new soil they attempt to grow in changes them. British folk clubs, Irish pub sessions and Hungarian táncház usually become different elsewhere once uprooted from their native habitat. The Herschell Arms is a freehouse in Park Street, Slough (as in the sly Robb Johnson song, She Lives In Slough, concerning a certain Slough-based royal). Let me contradict myself. The Herschell Arms was an Irish pub on in British soil that bust clichés, at least at the time that The Herschel Sessions was cut.

It includes live session recordings by Broderick (Luke Daniels, Clare Garrard, Colm Murphy and Don Oeters), Jenny Crook and Henry Sears, Cunásc (Paul Curran, Eric Faithful, Brian Hurst and Roger Philby), Herschel Street (Alan Burton, James Fagan, Steve Hunt and Nancy Kerr) and Don Mescall.

Kwela Ceilidh is a string duet for harp and mandolin by Jenny Crook and Henry Sears. Crook was apparently a finalist for the BBC’s Young Tradition Award in 1992 and contributed music to David Attenborough’s The Private Life of Plants while Sears has done sessions for Alison Moyet and the BBC. The tune just jumps out at the listener. I cannot comment on the continued availability of The Herschel Sessions CD but I found a reference to a version of the same tune (that I haven’t heard) as being on their Chasing the Dawn. This, however, would appear to have the tune’s first recorded excursion – happy to be contradicted – and highly effective it is too. From The Herschel Sessions (OSCD003, 2000)

More information at: www.jennifercrook.com

Ae Fond Kiss – Eddi Reader

Ae Fond Kiss – Eddi Reader

Adding to a month’s listening on Burns Night in January 2010 without adding something from the Scots Bard would be remiss. Eddi Reader’s rendition of Ae Fond Kiss (‘One Fond Kiss’ in Scots) is sublime, the way pain can be. But especially the pain of parting.

“Ae fond kiss, and then we sever/Ae fareweel [farewell], alas, for ever” – Burns’ opening lines are so simple and yet so telling. As songs of separation go, it knows few rivals in any language to my ken. Ae Fond Kiss, take it to your bosom and it will mean different things at different times in your life. Ae Fond Kiss is a love song of the profoundest ilk. Its line “For to see her was to love her” communicates a sense of loss and unconditional love and exerts a pull as few songs or pieces of poetry ever achieve. A song of love and parting for all seasons. From The Songs of Robert Burns (Rough Trade RTRADCDX097, 2008)

C Minor Complex – Lennie Tristano

Lennie Tristano (1919-1978) made piano solos maybe the like of which nobody had ever heard before. Here he is flying and delivering new lessons not only in how to play but in how to listen to jazz in 1962. I would imagine The New Tristano has lost not one jot of immediacy and impact down the years. Listening to what each hand is doing is a lesson in itself. This is the sort of music that parallels what was happening with the marvellous Jacques Loussier and his explorations of jazz from an alternative perspective on his trio’s Play Bach albums. (Remember how Play Bach No. 3 (Decca SSL 40 507, 1959) and Play Bach No. 5 (Decca SSL 40.205 S, 1964) felt?) From The New Tristano (Atlantic Masters 8122-77676-2 – the CD edition gives 1962 again)

Matapedia – Kate & Anna McGarrigle

Kate McGarrigle wrote songs. Anna McGarrigle wrote songs. Matapedia’s wonderful lyrics leave you guessing which sister wrote which bit of the song. Matapedia, the album, is one of their masterpieces. Whether individually or collectively Kate & Anna McGarrigle wrote some of the finest songs in the English and French languages and bequeathed them to posterity. Too close to Kate McGarrigle’s death to write anything more analytical. From Matapedia (Hannibal HNCD 1394, 1996)

Ken Hunt’s obituary of Kate McGarrigle in The Scotsman of 23 January 2010 is at http://news.scotsman.com/obituaries/Kate-McGarrigle.6007824.jp

The First Girl I Loved – The Incredible String Band

January 2010 saw me delivering an article about the Incredible String Band’s first five LPs. None of the re-mastered albums were available as I wrote that piece for R2. The day I was due to ping the article off, The Incredible String Band and 5000 Spirits landed on the doormat. 5000 Spirits played while doing the last-minute tweaks. Joe Boyd and John Wood – respectively, the producer and sound engineer on the original Elektra sessions – have done wonders with its master. First Girl I Loved, the last track on the album, left its mark yet again.

The remastered Robin Williamson was singing very clearly, “Well, I never slept with you/Though we must have made love a thousand times” a few days later when my daughter rang, prompting a startled “What are you listening to?” Strange the power of words and song. The song is eely and ends as an epistle. Robin was 23, coming on 24, when the album on which this appeared came out.

He took the song to new places subsequently, expanding it into an astonishing performance piece. Him doing the song with its spoken word section at Stagfolk, the folk club in Shackleford, off the Hog’s Back in Surrey, around 1980 still lingers as a memory. Annoyingly Southern Rag commissioned me but never ran the review. From The 5000 Spirits or The Layers of The Onion, Fledg’ling FLED 3077, 2010)

Look out for more information about the Incredible String Band reissue programme at The Bees Knees, “a music information archive and the home of Fledg’ling records”: www.thebeesknees.com

Ajab Si – KK

As a film Om Shanti Om is an exceptional mishmash/mash-up on a Bollywood pile-up scale, both cinematically and musically. It flips between past and present lives, past and present movies with lashings of the supernatural and rebirth, revenge and disco beats. The music is from Vishal & Shekhar and the lyrics are from Javed Akhtar.

As a film Om Shanti Om is an exceptional mishmash/mash-up on a Bollywood pile-up scale, both cinematically and musically. It flips between past and present lives, past and present movies with lashings of the supernatural and rebirth, revenge and disco beats. The music is from Vishal & Shekhar and the lyrics are from Javed Akhtar.

The film itself is tongue-in-cheek referential with allusions to Karz and a red carpet of Bollywood cameos, including the bow-down-and-be-so-very-humble-in-her-presence Rekha (Bhanurekha Ganesan) and that what’s-his-name? fellow from Sholay. This is maybe the least obvious track to pick from the soundtrack, much of which is decidedly upbeat and comes ringing with kitsch lines like “My heart is filled with the pain of disco”. That said, who gives a flying flip? Because it’s Bollywood, innit? From Om Shanti Om (T-Series/Super Cassettes Industries Limited SFCD 1-1261, 2007)

11. 2. 2010 |

read more...

[by TC Lejla Bin Nur, Ljubljana] Bonjour (Barclay/Universal, 2009) is Rachid Taha’s eighth studio album since he started on his solo path in 1990. During this time he had released at least two Best Ofs, a hefty pile of remixes, extras & vinyl for collectors and a few concert albums and projects, notably the world-wide resounding success 1, 2, 3, Soleils with Khaled and Faudel in 1998. Before all that, way back in 1980’s, he also recorded about two and a half albums with his band Carte de Sejour. To sum up, he’s come a long way and produced an opulent harvest of quality music that dexterously evades genre labels; in his melting pot he brews rock welded to electro, wrought with music of the world from just about everywhere, obviously and particularly North Africa – all together often encrusted with pop glitter and sometimes even permeated with its essence. After his masterpiece Made in Medina (2000), the coarser Tekitoi (2004) and both his own rootsy compositions on the cover album Diwan 2 (2006) it seemed that this roseate sugar encrustation more or less has fallen off for good in the ripe maturity epoch of master Taha. However, last autumn, a little before All Saints, he struck again with new, screamingly roseate album Bonjour, its soundscape jingling with a wide variety of cheap sweetmeats.

[by TC Lejla Bin Nur, Ljubljana] Bonjour (Barclay/Universal, 2009) is Rachid Taha’s eighth studio album since he started on his solo path in 1990. During this time he had released at least two Best Ofs, a hefty pile of remixes, extras & vinyl for collectors and a few concert albums and projects, notably the world-wide resounding success 1, 2, 3, Soleils with Khaled and Faudel in 1998. Before all that, way back in 1980’s, he also recorded about two and a half albums with his band Carte de Sejour. To sum up, he’s come a long way and produced an opulent harvest of quality music that dexterously evades genre labels; in his melting pot he brews rock welded to electro, wrought with music of the world from just about everywhere, obviously and particularly North Africa – all together often encrusted with pop glitter and sometimes even permeated with its essence. After his masterpiece Made in Medina (2000), the coarser Tekitoi (2004) and both his own rootsy compositions on the cover album Diwan 2 (2006) it seemed that this roseate sugar encrustation more or less has fallen off for good in the ripe maturity epoch of master Taha. However, last autumn, a little before All Saints, he struck again with new, screamingly roseate album Bonjour, its soundscape jingling with a wide variety of cheap sweetmeats.

Album Bonjour wasn’t produced by Taha’s long term collaborator Steve Hillage, the producer of most of Taha’s previous band and solo opus. This time, the producers are New Yorker Mark Plati (who has collaborated with, among others, David Bowie, The Cure) and Gaetan Roussell, the leader of the well known French band, Louise Attaque. Roussell also wrote the music and some of the lyrics for the title song Bonjour, composing three more songs in collaboration with Plati and of course with Rachid Taha, the author of the majority of the music and lyrics. Also new is the ample team of various musicians that recorded this album with Rachid Taha at studios in Paris and New York; only mandolute master Hakim Hamadouche remains from former albums and live performances.

Rachid Taha claims that he gathered this fresh team with a purpose, to bring a new wind to his new album, however (in my opinion) that wind blows from the stifling port and stuffy shopping centre of a Megapolis, not from the spacious seascapes and airy deep spaces of the universe. The rhythms are less interesting, a bit monotonous. Here and there they don’t agree and sometimes come to blows. The same goes for a myriad of various sounds and sound crumbs as well as for the Rachid Taha’s proverbial marriage between Euro-American and North African popular genres; as far as we can even still talk about the latter. Rachid’s vocals are rather straight and one-sided, less multiple, more or less not taken advantage of enough in all its expressive potentials (such as onomatopoetic sounds), probably because the producers don’t know him well enough to know exactly what to do with his voice. And yet Bonjour is still, despite the annoying bits and pieces, punctuated with rare outstanding moments, a solid product of contemporary popular music with Taha’s distinctive beyond-genre flavour.

Taha’s selection of 10 short pieces (allegedly radio friendly 3 to 4 minutes) starts with the love-pleonasm Je t’aime mon amour (I love you my love) and continues with the story of the homeless tramp Mokhtar which offers a hand to Ha Baby, a statement of universal love, which bounds into the title-song Bonjour which claps hands with North African rap Taha style, Mine jai (Where are you coming from). This one goes on into the birth of humanity Mabrouk aalik (Congratulations) which spills onto otherwordly Ile liqa (See you soon), followed by It’s an Arabian song, a duet with French singer and Taha’s old pal Bruno Maman, with whom he also wrote the music, while Rachid’s lyrics are short: “Good is better than evil. Never forget.” The penultimate track, Selu (Ask) with its solid drive, is a tribute to all great minds, the phrase “ask angels” (selu el maleika) is also a wordplay with title-song Bonjour or Salam aleikum. At the end the circle comes around and fastens the way it was opened, with the sensuous and sensitive love lure Agi (Come).

10. 2. 2010 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Peggy Seeger was one of people like Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Big Bill Broonzy and Cisco Houston whose records introduced Britain to an authentic lexicon of Americana. That word didn’t exist in the 1950s but if it had those musicians would have pretty much defined it. In that period, as far as Cold War Britain of the 1950s was concerned, American music was a unholy trinity of the crypto, wannabe and cod. Skiffle, Britain’s first youth movement, was a hugest craze but, as an American, Peggy Seeger had a head start.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Peggy Seeger was one of people like Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Big Bill Broonzy and Cisco Houston whose records introduced Britain to an authentic lexicon of Americana. That word didn’t exist in the 1950s but if it had those musicians would have pretty much defined it. In that period, as far as Cold War Britain of the 1950s was concerned, American music was a unholy trinity of the crypto, wannabe and cod. Skiffle, Britain’s first youth movement, was a hugest craze but, as an American, Peggy Seeger had a head start.

By the time Peggy officially relocated to England in 1959, the folk scene was largely a young person’s scene. A decade on, when I saw her with Ewan MacColl (1915-1989), every time I saw them he whiplashed me back to my schoolboy days and sitting on a form in school assembly. He had a headmasterly hauteur towards folk club audiences. That British folk scene regularly felt like two diary-keepers from opposing sides documenting a battle. One faction I understood: and the MacColl-Seeger one had nothing in common with what I was experiencing, with my life, with my music.

When she emerged after MacColl’s death in October 1989, my ears felt less biased. It began with reviewing her 1992 Smithsonian Folkways anthology Songs of Love and Politics – a great record – for Q magazine and being charmed and captivated by her takes on traditional and non-traditional songs. The quality of her voice and what she was communicating lifted the latch. There were some traditional songs like Pretty Saro and Broomfield Hill. Yet it was the discovery of her own feminist observations on male conditioning such as Lady, What Do You Do All Day? and, especially, Gonna Be An Engineer that caused me to ditch my Seegerish blinkers.

The sheer quality of what she has brought to the folk scene is incalculable. Enough of ruminating: time to let her to talk.

The sheer quality of what she has brought to the folk scene is incalculable. Enough of ruminating: time to let her to talk.

To kick off, I wondered how you felt the creative process has changed for you over the course of your musicianly life?