Articles

[by Ken Hunt, London] The US record producer, engineer and mixer Greg Ladanyi, who worked with, amongst others, Jackson Browne, Fleetwood Mac, Jeff Healey, Don Henley, Los Jaguares, David Lindley and Warren Zevon, died on Cyprus on 29 September 2009. He died of the consequence of an accident on stage whilst touring with the Greek Cypriot singer Anna Vissi whose album Apagorevmeno (2008) he had co-produced.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The US record producer, engineer and mixer Greg Ladanyi, who worked with, amongst others, Jackson Browne, Fleetwood Mac, Jeff Healey, Don Henley, Los Jaguares, David Lindley and Warren Zevon, died on Cyprus on 29 September 2009. He died of the consequence of an accident on stage whilst touring with the Greek Cypriot singer Anna Vissi whose album Apagorevmeno (2008) he had co-produced.

Ladanyi won a Grammy Award for ‘Best Engineered Recording – Non-Classical’ with his co-engineered Toto IV in 1982 – a period that found the session musician spin-off band Toto at a peak of their critical and commercial success. He was also nominated for production or engineering work on Don Henley’s The Boys Of Summer in 1986 and, at the 1st Annual Latin Grammy Awards in 2000, Los Jaguares’ Bajo el Azul de Tu Misterio.

He first came to the attention of people who scrutinise the small print of record sleeves with his credits on Warren Zevon’s Bad Luck Streak in Dancing School (Elektra, 1980) – which he co-produced with Zevon – and Zevon’s live album Stand in the Fire (Asylum, 1980) – which contained many of the hallmarked songs with which Zevon was closely identified including Excitable Boy, Mohammed’s Radio, Werewolves of London, Poor Poor Pitiful Me and I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead at this stage of his career.

In 1980 he also landed his first credit – as co-producer – with another Asylum act, Jackson Browne, on his Hold Out (1980) (having begun work with Browne on The Pretender (1976)). The following year he and Browne co-produced David Lindley’s raucous and refined debut El Rayo-X (Asylum, 1981). Other work he was associated with included Zevon’s The Envoy (1982), Browne’s Lawyers in Love (1983), Henley’s Building the Perfect Beast (1984) and The End of the Innocence (1989), The Jeff Healey Band’s See The Light (1988) and Clannad’s Sirius (1987) and Fleetwood Mac’s Behind the Mask (1990).

7. 10. 2009 |

read more...

Ken Hunt looks back on a month’s listening reflecting music influenced by work, travel and returning home. The moments are supplied this time by Cass Meurig and Nial Cain, Angelika Weiz & GVO, Ravi Shankar, Judee Sill, the Velvet Underground, the Young Tradition, Johnny Jones, Roy Nathanson, Asha Bhosle and Rahul Dev Burman and Ewan MacColl. As ever, the ten selections are in no particular order. Their only link is that over the month none of them did a bunk.

28. 9. 2009 |

read more...

Ken Hunt looks back on a wonderful month in music, advanced somewhat because of travel, provided by Amira Medunjanin and Merima Ključo, Bea Palya, Mike Seeger, Sachal Studios Orchestra, Tim Buckley, Faustus, Martina Musters-Musters, Johanna Huygens-Musters and Suzanna de Vos-Musters, Fernhill, Bai Hong and David Crosby. As ever, the ten selections are in no particular order and the only link is that none of them would go away.

Karanfil Se Na Put Sprema – Amira Medunjanin and Merima Ključo

Karanfil Se Na Put Sprema – Amira Medunjanin and Merima Ključo

Amira’s London debut in 2007 at the Barbican was memorable. “Amira was born at a time when the popularity of traditional music in the former Yugoslavia was at high tide,” it says on her website. On this recording – Zumra means ‘Emerald’ – the mood is largely sombre. The Bosnian tune Karanfil Se Na Put Sprema is an exception. Elsewhere Ključo’s accordion evokes comparisons with the splendid American avant-garde composer Pauline Oliveros.

In my head, the cover artwork connected with photojournalist Valdrin Xhemaj’s images from Kosovo of traditional Torbesh wedding customs in which the bride’s face is painted to fend off bad luck.

From Zumra (Gramofon GCD1017, 2008)

www.gramofon.ba

www.amira.com.ba

Mindenkinek Kurványja – Bea Palya

Mindenkinek Kurványja – Bea Palya

Coiled energy. Bea Palya sashays, sways, stamps and sings on this track. Its title translates as ‘To Hell with everyone’. A fiery reflection on past mistakes and miscreant married men. In it she consigns the latter to Hades, entreating them, to paraphrase Kurt Vonnegut’s oft-overlooked Hungarian period, to take a flying fuck at a donut. Welcome to the trials of life, Benedek – a Hungarian arrival on 8 August 2009. From Egyszálének/Justonevoice (Sony Music Entertainment Hungary 88697536052, 2009)

http://www.palyabea.hu/en/

Did You Ever See The Devil, Uncle Joe? – Mike Seeger

Very often the pattern was that you first heard a piece of folk music performed by a revivalist, then you backtracked. I first heard Uncle Joe on Buffy Sainte-Marie’s I’m Gonna Be A Country Girl Again in 1968. Mike Seeger’s marvellous version is a long journey, him first having heard it as a fiddle tune performed by Field Ward (vocals/guitar) and Wade Ward (banjo). His version here on jew’s harp and voice reminds why he was such an inspirational musician. Hearing him gulping down air rather than multi-tracking his vocal part really earths the performance. From True Vine (Smithsonian Folkways SFW CD 40136, 2003)

http://mikeseeger.info/

Ken Hunt’s obituary of Mike Seeger:

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/mike-seeger-folk-mus ician-who-influenced-bob-dylan-and-the-grateful-dead-1775851.html

Take Five – Sachal Studios Orchestra

The 5:42 version. “I was ten years old when I first heard Take Five in Lahore (Pakistan) courtesy of the music centre of the United States Information Service,” writes Izzat Majeed in the notes to this CD single. There is a symmetry to the Sachal Studios Orchestra’s choosing to indianise the Dave Brubeck hit.

Brubeck kicked so much off when it came to Indo-jazz fusion. In 1958, the Dave Brubeck Quartet – courtesy of the US State Department and the Eisenhower Fund – did a whistle-stop, international tour that took them to England, West Germany and Poland, Turkey, Iran and Iraq, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Ceylon.

The trip seeded a number of compositions, most famously the ‘oddly metered’ – 9/8 (2+2+2+3=9) – Blue Rondo a la Turk (Time Out, 1959) but also the impressionistic Calcutta Blues (Jazz Impressions of Eurasia, 1958) with the band’s rhythmist Joe Morello mimicking tabla with his hands.

This version of the 1959 Brubeck hit has Ballu Khan on tabla, Nafees Ahmad Khan on sitar, Tanveer Hussain on Spanish guitar and sarod, Asad Ali on Spanish guitar and bass, Chris Wells on drums and huge string section of violins, violas and cellos. Interestingly, Paul Desmond, its composer, bequeathed its royalty income to the American Red Cross – a good model when it comes to will writing for posterity. (CD single, Sachal Music SM005, 2009)

http://www.sachal-music.com/

Troubadour – Tim Buckley

Troubadour – Tim Buckley

Two versions of the same song to illustrate how songs change and mature. The Folklore Center version, recorded by the Center’s Izzy Young, is Tim Buckley (1947-1975) alone with his guitar. The Queen Elizabeth Hall concert from 10 July 1968 finds him and his guitar accompanied by David Friedman on vibraphone, Lee Underwood on guitar and Pentangle’s Danny Thompson on double bass.

The 1967 version is faster and tauter lyrically. The 1968 one has a medium tempo, less advanced lyrics and a middle section with “Sing songs for pennies/Tip my hat couldn’t get many/All around the city are the troubadours”. The earlier Folklore Center cut has no reference to any sort of troubadour at all.

Buckley has been the subject of biography, bootlegs and archival trawlings since his death. The 1967 recording parts the veil to offer a glimpse at Buckley’s folk troubadour period. The QEH concert version is more folk-rock with folk-jazz shadings. He was 20 and 21 when he made these two recordings. And dead at 28. From Live At The Folklore Center, NYC – March 6, 1967 (Tompkins Square TSQ2189, 2009) and Dream Letter – Live In London 1968 (Enigma Retro/Straight 7 73507-2, 1990)

www.timbuckley.net

www.tompkinssquare.com

Ballina Whalers/The 8th of July – Faustus

Faustus are Paul Sarlin (of Bellowhead), Benji Kirkpatrick (of Bellowhead and Seth Lakeman) and Saul Rose (of Waterson Carthy). Their Ballina Whalers is taken from Nic Jones’ The Humpback Whale on his masterpiece Penguin Eggs. Actually, its proper title is The Ballina Whalers and it’s from the pen of the Scots-born Australian songwriter, Harry Robertson (1923-1995). Faustus pitch their delivery with an undercurrent of feeling that accords with whalers out on the ocean and a long way from home. After a couple of feints, the tune The 8th of July emerges. From Faustus (Navigator 5, 2008)

www.myspace.com/faustustrio

For more about Nic Jones and Penguin Eggs, a certain Canadian magazine has a little history at www.penguineggs.ab.ca/peggs.php?page=nicjones

Een jeugdig schoon bloem was uitgegoan – Martina Musters-Musters, Johanna Huygens-Musters and Suzanna de Vos-Musters

The title translates as ‘A lovely young blossom went out’. Hand on heart, Onder de groene linde (‘Under the green linden [tree]’) gives me the shivers because it defies expectations and is such a declaration of Dutch culture. I began with the Dutch Folk Revival, thanks to Wolverlei. Top tip: always try to start at the top.

This folksong has roots and branches in many Western European cultures where languages blur into each other and intergrades abound. The Musters sisters, recorded here in March 1968 in Ossendrecht, sing a song which combines beery and winey talk, deception and a broadmindedness that shames the bawdiness associated with such matters in many cultures’ folkways. Best of all, they sing like a dream. From volume 4, Van een Heer die in een Wijnhuis sat (‘About a Lord who sat in a Wine-house’) of Onder de groene linde (Music & Words MWCD 4900, 2008)

Bredon Hill – Fernhill

Divadlo na prádle is one of Prague’s theatre venues and Czech Radio (Český rozhlas 3) captured the Welsh trio there on 9 March 2006. Bredon Hill opens with acoustic guitar from Ceri Rhys Matthews before Julie Murphy sweeps in with a magisterial vocal. With consummate restraint the arrangement bides its time before Tomos Williams adds droplets of trumpet before a fuller flood of notes pours out.

Bredon Hill is a musical setting from A.E. Houseman’s 1896 book of verse, A Shropshire Lad. They tweak the poem at one point – to my mind for the better. In the verse “The bells would ring to call her/In valleys miles away:/’Come all to church, good people; Good people come and pray.’ But here my love would stay”, they substitute her with us opening up the lyric.

PS Czech pub and place names are a continual source of joy. Divadlo na prádle means ‘Theatre at the laundry’. From Na prádle (Beautiful Jo Records bejocd-51, 2007)

www.myspace.com/fernhillmusic

www.bejo.co.uk

Listen Up – Bai Hong

In the 1930s the Shanghai (“The Hollywood of the East”) hothouse created music that ranks alongside Bollywood in terms of making use of whatever was around and dropping it into the melting-pot. Only Shanghai predates Bombay, as even a cursory comparison of the two centres’ output from the 1930s swiftly shows.

Bai Hong (1919-1992) sings a Mandarin (don’t quote me) lyric over a slow drag that would do Cab Calloway proud. The piano and horn parts are derivative. (Spot the stolen melodic motif that the piano plays about 50 seconds in and then never repeats, a theft as chutzpah as anything Bollywood pulled off.) What she creates is magnificent. In revolutionary times Bai’s back-catalogue was out of bounds yet, a true survivor, she negotiated herself a continuing career in theatre. It’s life-affirming that this music survived at all.

The pointless 2003 remix (“Disc 1: Shanghai Lounge Divas – Original 1930’s (sic) Sessions Remixed For Today”), on the other hand, has about as much integrity as a pail of shit – and is of far less use. Judgemental, moi? From Shanghai Lounge Divas (EMI Music (Hong Kong) 7243 4 73058 25, 2004)

David Crosby – Cowboy Movie

David Crosby – Cowboy Movie

In 1971 the Bundespost brought a COD (cash on delivery) package from a Hamburg record shop. Inside was If Only I Could Remember. Track two was Cowboy Movie.

It opens with some blasts of Neil Young guitar. Less than a minute in, a second electric guitar emerges in the mix. That guitar is Jerry Garcia’s. Sonically what was there not to love? On a historical note, trainspotters tell me it was the only time they were recorded and released duetting.

All the while, Crosby is singing some tale about cowboys. However, clearly this is no hippy idyll. Allegory rules and Crosby roars. Apparently, it concerns Crosby, Nash, Stills & Young. In this here cowboy flick Crosby is ‘Old Weird Harold’ (I sang the wrong words for years), Nash is the Dynamiter, Stills is Eli and Young is Young Billy. & the Indian lass, it turned out, was Rita Coolidge. Well, I’ll be darned. From If Only I Could Remember My Name (Atlantic/Rhino R2 73204, 2006) and Voyage (Atlantic/Rhino 8122-77628-2, 2006)

26. 8. 2009 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Neil Young once stated, “The great Canadian dream is to get out.” It was certainly what three fifths of Buffalo Springfield did when they joined the California-based rock group’s US contingent, Stephen Stills and Richie Furay. In 1966 Young and Bruce Palmer – the band’s original bassist – had headed south in a 1953 Pontiac hearse with Ontario plates. Minds set on forming a rock group and already working up Young’s Nowadays Clancy Can’t Even Sing, Furay and Stills famously spotted the Canadians driving in the opposite direction on Sunset Boulevard. (Stills had already met Young in Thunder Bay, Ontario and had been taken.) Furay executed some nifty pursuit-chase driving and caught up with them before they hit the highway to head home. Four fifths of Buffalo Springfield were in place.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Neil Young once stated, “The great Canadian dream is to get out.” It was certainly what three fifths of Buffalo Springfield did when they joined the California-based rock group’s US contingent, Stephen Stills and Richie Furay. In 1966 Young and Bruce Palmer – the band’s original bassist – had headed south in a 1953 Pontiac hearse with Ontario plates. Minds set on forming a rock group and already working up Young’s Nowadays Clancy Can’t Even Sing, Furay and Stills famously spotted the Canadians driving in the opposite direction on Sunset Boulevard. (Stills had already met Young in Thunder Bay, Ontario and had been taken.) Furay executed some nifty pursuit-chase driving and caught up with them before they hit the highway to head home. Four fifths of Buffalo Springfield were in place.

Dewey Martin completed the line-up in April 1966. It was widely believed he was American too. In fact he had been born Walter Milton Dewayne Midkiff in Chesterfield, Ontario on 30 September 1940 – ‘Dewey’ was a longstanding nickname and Midkiff was a mouthful – and grew up in Ottawa. He had already embraced the Great Canadian Dream and emigrated to the States. After US national service, he fetched up in Nashville at the beginning of the 1960s. He strove to break into its country scene, drumming on sessions and in touring bands. By 1963 he was playing with Faron Young and when the tour got to Los Angeles he liked the place so much he stayed. On the West Coast he played with Sir Raleigh and the Coupons (another of those bogus British Invasion groups), The Sons of Adam, the Modern Folk Quartet, the Standells and the Dillards.

Dewey Martin completed the line-up in April 1966. It was widely believed he was American too. In fact he had been born Walter Milton Dewayne Midkiff in Chesterfield, Ontario on 30 September 1940 – ‘Dewey’ was a longstanding nickname and Midkiff was a mouthful – and grew up in Ottawa. He had already embraced the Great Canadian Dream and emigrated to the States. After US national service, he fetched up in Nashville at the beginning of the 1960s. He strove to break into its country scene, drumming on sessions and in touring bands. By 1963 he was playing with Faron Young and when the tour got to Los Angeles he liked the place so much he stayed. On the West Coast he played with Sir Raleigh and the Coupons (another of those bogus British Invasion groups), The Sons of Adam, the Modern Folk Quartet, the Standells and the Dillards.

Buffalo Springfield were pretty volatile. They landed an engagement as the temporary house band at the Whisky a Go Go on Sunset Strip. Yet when they performed at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival, Young was not on stage. Stills and Young continually vied for supremo status – and made no real effort to contribute to the band’s biography, For What It’s Worth: The Story of Buffalo Springfield. At one point Martin beat off a coup to be replaced and there were factions and fractiousness from very soon after the band’s founding.

Buffalo Springfield (1966) and Buffalo Springfield (1967) – originally with the working title Stampede – were the only true albums released during their lifespan. By May 1968 they had imploded and Last Time Around (1968) was a sellotaped-together, contractual obligation affair.

Buffalo Springfield (1966) and Buffalo Springfield (1967) – originally with the working title Stampede – were the only true albums released during their lifespan. By May 1968 they had imploded and Last Time Around (1968) was a sellotaped-together, contractual obligation affair.

The 4-CD boxed set Buffalo Springfield (2001) contained much good stuff but failed to live up to expectations or hopes. It lacked all trace of what had come down by repute and word-of-mouth as their forte: fiery live exchanges and stage jamming. It may count as one of the lamest box sets ever released. It failed to deliver, hence its popularity in second-hand record shops.

Despite post-Springfield forays with, for example, Dewey Martin’s Medicine Ball and various Buffalo Springfield spin-offs and tribute bands, Martin set music aside for a livelihood as car mechanic. A Buffalo Springfield reunion involving the original quintet collapsed and Palmer’s death in 2004 put the seal on that hoped-for project.

Dewey Martin died in Van Nuys, California on 31 January 2009.

Further reading: John Einarson and Richie Furay’s For What It’s Worth: The Story of Buffalo Springfield (1997, revised 2004)

25. 8. 2009 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt and Peter Bellamy: London] In 1986 after one of his concerts the English folksinger Pete Bellamy and I formulated the idea of Giant Donut Discs ®. It came out of a conversation about the wish to create a mutant version of Roy Plomley’s Desert Island Discs BBC radio programme – http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b006qnmr – for the magazine Swing 51.

Instead of the stranded person coming up with tracks to take to the proverbial desert island, Pete and I wanted something capricious, totally of the moment, something that was ten pieces of music that were filling people’s heads right then and now – not the considered weightiness of someone stranded on the BBC’s desert island.

The principle was first thoughts, best thoughts – the old Beat adage. At the heart of the choices were the moment and passion (however fleeting), perhaps tinged sometimes with a few things packed into the old kit bag. It was a massive success.

Some people explained, some people just gave a list of the here and now. Giant Donut Discs continues in memory of Peter Franklyn Bellamy (8 September 1944-21 September 1991).

To give an idea of how it worked and why it worked, here is an annotated version of Peter Bellamy’s choices from Swing 51 issue 13/14. Peter had a fairly bare-boned approach to the column. And, although I encouraged him to expand on his selections, he never did. Hence the annotations and updates here.

Sidewalk Blues – Jelly Roll Morton’s Red Hot Peppers

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation transcription.

Ken Hunt: From a 1984 Australian Broadcasting Corporation anthology that also included King Oliver & his Dixie Syncopators, Ma Rainey, J.C. Cobb & His Grains of Corn and others – Robert Parker’s now-deleted second volume of jazz classics in ho-ho-ho “digital stereo”. No doubt he encountered it on some Australian tour.

Raglan Road – Van Morrison & The Chieftains

Ken Hunt: From Van Morrison & the Chieftains’ Irish Heartbeat (Exile/Polygram, 1988, reissued 1998).

Wild Man In The City – Manu Dibango

Wild Man In The City – Manu Dibango

He’s a saxophonist from Cameroon. From the LP, O Boso.

Ken Hunt: From Manu Dibango’s O Boso (London Records DL 3006, 1972).

Worried About You – Rolling Stones

Ken Hunt: “Sometime I wonder why you do these things to me/Sometime I worry, girl that you ain’t in love with me/Sometime I stay out late, yeah I’m having fun/Yes, I guess you know by now you ain’t the only one.” It would be impossible to say which recording Pete had in mind when he chose this track from Tattoo You (1981). He adored the Stones and took great delight in their, ahem, obscurer recordings.

Drown In My Own Tears – Ray Charles

Drown In My Own Tears – Ray Charles

– From 1959. Live.

Ken Hunt: Live was new in 1987. Pete liked the sound of good, old gutbucket blues.

The Mountain Streams Where The Moorcock Crow – Paddy Tunney

Ken Hunt: Currently available on Paddy Tunney’s Man Of Songs (Folk-Legacy CD-7). From a field recording by Diane Hamilton.

These Memories of You – The Trio

The Trio being Dolly Parton, Linda Ronstadt and Emmylou Harris.

Ken Hunt: The Trio (1987) was another brand new album when he chose this track. A simply astonishing album, Robert Christgau reviewed it in the July 1987 issue of Playboy saying, “By devoting herself to Nelson Riddle and operetta, Sun City stalwart Linda Ronstadt has made boycotting painless; but her long-promised hookup with Dolly Parton and Emmylou Harris, Trio (Warner), will be hard to resist for those with a weakness for the vocal luxuries of the mainstream record biz. An acoustic-country album meandering from Farther Along and Jimmie Rodgers to Kate McGarrigle and Linda Thompson, Trio is a literally thrilling apotheosis of harmony – three voices that have thrived and triumphed individually engaged in heartfelt cooperation. Free of tits, glitz and syndrums for the first time in a decade, Parton’s penetrating purity dominates the album as it once did country-music history. The only one of the three who’s had the courage of her roots recently, Harris sounds as thoughtful up front as she does in the backup roles that are her forte. And while Ronstadt’s big, plummy contralto will always hint of creamed corn, she’s a luscious side dish in this company.” Review lifted from www.ronstadt-linda.com

Rabbit And Log – The Stanley Brothers

Ken Hunt: The title should have been Rabbit In A Log.

Everybody Needs Somebody To Love – Wilson Pickett

Ken Hunt: Pete was no more catholic in his musical tastes than many other singers on the British folk scene. He would descend on record collections at places he was staying and demand fixes of the familiar or the unknown. I can imagine him getting in from a performance or sitting at home making up a cassette compilation and singing along (in accent) to this: “Sometimes I feel, I feel a little sad inside/When my baby mistreats me, I never, never have a place to hide, I need you!”

I Was Born To Preach The Gospel – Washington Phillips

I Was Born To Preach The Gospel – Washington Phillips

Ken Hunt: Washington Phillips cut a handful of records in Dallas, Texas over five sessions from 1927 to 1929. The correct title in fact is I Am Born To Preach The Gospel. Most likely, Peter had it – or had taped it – from Songsters & Saints – Vocal Traditions on Race Records Vol. 1 released on the UK Matchbox label in 1984.

The song is currently available on The Key To The Kingdom (Yazoo 2073). There is an excellent discography of Washington Phillips compiled by Stefan Wirz at http://www.wirz.de/music/philwfrm.htm

(c) 1989, renewed 2009 Swing 51

From that same issue here are mine with annotations and updates:

Don’t Tempt Me – Richard Thompson

Don’t Tempt Me – Richard Thompson

The opening track from Amnesia. For its astonishing vocal performance.

Ken Hunt: Richard Thompson remains a constant ingredient in any balanced musical diet. Lest we forget.

Pride of Cucamonga – Grateful Dead

For the tune, the lyrics and John McFee’s pedal steel part.

Company Policy – Martin Carthy

It may be another song about the Falklands but it taps into the human element superbly. From the long overdue Right of Passage.

Ken Hunt: It had been some while since Martin Carthy had made a solo album.

The 1982 Falklands business – also known as the Guerra de las Malvinas – was still preying hard on people’s minds. Martin Carthy’s song about the “company store” was one of the great songs, like John B. Spencer’s Acceptable Losses (reissued on Three-Score-And-Ten (TOPIC70, 2009)), that came out of the war.

Eight Miles High – The Byrds

Eight Miles High – The Byrds

From Never Before. A tenser, rawer reading than the Fifth Dimension cut.

Ken Hunt: The Byrds were and remain a continual reference point.

Devil’s Right Hand – Webb Wilder & The Beatnecks

A fabulous song by Steve Earle that Peter Case introduced to me in a private moment. For the opportunity to namedrop too.

Me And Billy The Kid – Joe Ely

For its lyrics. Love the line about shooting their mutual girlfriend’s chihuahua.

Calvary – The Alabama State Sacred Harp Convention

From the 1960 album White Spirituals, the fourth volume in Atlantic’s Southern Folk Heritage series. A hymn as mighty as the ocean. “My thoughts that often mount the skies/Go, search the world beneath/Where nature all in ruins lies/And owns her sovereign – Death!”

Ken Hunt: This was an introduction by Gill Cook from Collet’s – whose obituary I later wrote. A very good friend and a source of inspiration and solidarity.

My obituary of Gill Cook from The Independent:

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/gill-cook-524805.html

Tony Russell’s from The Guardian:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/2006/feb/07/guardianobituaries.artsobituaries

The King of Rome – June Tabor

For its triumph over adversity.

Ken Hunt: Nearly two decades on, I did the song-by-song interviews and wrote the booklet notes to June’s career retrospective Always (Topic Records TSFCD4003, 2005) – on which this also appears.

Even A Dog Can Shake Hands – Warren Zevon

Even A Dog Can Shake Hands – Warren Zevon

For anybody who has ever been fleeced and has considered taking somebody to the Small Claims Court. From the strangely titled Sentimental Hygiene.

Ken Hunt: The magazine was going through a hard time financially and though various people rallied round and helped fund issue 13/14, the losses of the previous years I had absorbed proved too much to sustain and survive. The magazine went under. (The cumulative amount owed by companies that had defaulted on payment or themselves went under would have paid for another issue.) That was the background to choosing this remarkable track. RIP Warren William Zevon (24 January 1947-7 September 2003).

Pharaoh – Richard Thompson

The closing track from Amnesia. For its lyrics.

Ken Hunt: See Don’t Tempt Me above.

(c) 1989, renewed 2009 Swing 51

24. 8. 2009 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Dutch counter-culture poet, writer and painter Simon Vinkenoog died in Amsterdam on Saturday, 12 July 2009, a few days before his 81st birthday. Born on 18 July 1928 in Amsterdam, Vinkenoog was the child of a lone parent family raised in the De Pijp part of Amsterdam’s Oud-Zuid (Old South) district.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Dutch counter-culture poet, writer and painter Simon Vinkenoog died in Amsterdam on Saturday, 12 July 2009, a few days before his 81st birthday. Born on 18 July 1928 in Amsterdam, Vinkenoog was the child of a lone parent family raised in the De Pijp part of Amsterdam’s Oud-Zuid (Old South) district.

As a writer, he became part of the Netherlands’ post-war flowering of small literary titles, editing the short-lived magazine Blurb followed by the bloemlezing (anthology) Atonaal – a manifesto of intent of the literary collective self-styled ‘atonal poets’ known as the Vijftigers (50ers). Coinciding with this Dutch and Belgian (Flemish) movement’s emergence, from 1948-56 he lived in Paris – as ever a literary magnet of a place but especially then in the post-Second World War years. He was very much a reflection and an advancement of the times.

In the 1960s he was part of the new wave of writers influenced by what was going on around them. For example, he wrote about LSD and made his first record with the Dutch singer Frank Boudewijn de Groot, collaborating on the single Captain Decker b/w Steps Into Space. In June 1965 he appeared at London’s Royal Albert Hall in the glad company of Gregory Corso, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Allen Ginsberg, Christopher Logue, George Macbeth, Adrian Mitchell, Alexander Trocchi and others.

His works ran from Wondkoorts (1950) via Jack Kerouac in Amsterdam and Moeder Gras (both 1980) through the Ginsy-inspired Me and my peepee (2001) to Am*dam Madmaster (2008). In the Noughties he collaborated on disc with Spinvis, the one-man-band on Ja! (2006) and 2000-copy limited edition Ritmebox (2008). He also campaigned for the legalisation of cannabis. Superlatively, without stooping to Dutch cliché, from 2004 he was the Netherlands’ Dichter des Vaderlands (‘Poet of the Fatherland’), equivalent to Britain’s Poet Laureate.

Further reading: http://www.iisg.nl/collections/vinkenoog.php

7. 8. 2009 |

read more...

Ken Hunt’s month in music – the stuff in no particular order that either wouldn’t let go or wouldn’t go away.

31. 7. 2009 |

read more...

[by Ken Hunt, London] Forty years or so ago, Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger released their most recondite project, the two-volume Paper Stage. It was reconstructions of the first Elizabethan Age’s theatre for the second Elizabethan Age. The original peddlers of these more unauthorised than guerrilla playlets in song left few traces and fewer fingerprints. All that survived was the printed page. Theirs was street theatre, the equivalent of graffiti artist Banksy’s Mona Lisa with a rocket launcher, or that Banksy rat sawing a getaway hole to freedom through the pavement. Without forcing the analogy, the Paper Stage material somehow survived on paper without the accompanying music, just as Banksy’s long-gone, ephemeral spray paintings and stencil art images survive as photographic images in the book Wall And Piece without the walls.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Forty years or so ago, Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger released their most recondite project, the two-volume Paper Stage. It was reconstructions of the first Elizabethan Age’s theatre for the second Elizabethan Age. The original peddlers of these more unauthorised than guerrilla playlets in song left few traces and fewer fingerprints. All that survived was the printed page. Theirs was street theatre, the equivalent of graffiti artist Banksy’s Mona Lisa with a rocket launcher, or that Banksy rat sawing a getaway hole to freedom through the pavement. Without forcing the analogy, the Paper Stage material somehow survived on paper without the accompanying music, just as Banksy’s long-gone, ephemeral spray paintings and stencil art images survive as photographic images in the book Wall And Piece without the walls.

The year The Paper Stage came together – 1968 – was a year of great flux. It seemed as if it might turn into a watershed year, another 1848 in revolutionary terms. The Vietcong were on the offensive, in the USA Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy were gunned down, Paris, if not France, had its événements and Alexander Dubcek’s Prague Spring was chain-sawed in the bud by Warsaw Pact troops. As frequently happens under repressive regimes, a blossoming of literature and folk poetry occurs. The eight broadside ballads that are The Paper Stage‘s raw material were circulating in a similarly politically charged climate. They were by-products of xenophobia, fear of religious extremists and religious intolerance. Gerontus, The Jew Of Venice reflects that, while A Warning Piece To England Against Pride And Wickedness says it all in the title. “Anything was grist to the mill for the broadside,” laughs Peggy Seeger. “Somebody said, a cat only needs to peep round the corner and some broadsheet seller is selling it by the yard.”

The street performers that delivered these pieces then ducked and dived to sidestep censorship that coloured, conditioned and encrypted Elizabethan and Jacobean plays. Theatre was trickle-down television and film combined. Or like modern-day Trotters and Arthur Dalys they flogged their potted, pirated Taming Of The Shrew or King Lear And His Three Daughters wares to make their daily bread.

The Paper Stage is abridged theatre with a turn of speed, ready to leg it when the lookouts spot the Tudor regime’s killjoys bee-lining towards the gathering. That idea planted a seed. MacColl, Seeger and the Critics Group’s John Faulkner, Sandra Kerr and Dick Snell contemporised their instrumentation deliberately evoking the getaway spirit with portable instruments. They play modern-day ‘folk instruments’ – guitar, tin whistle, concertina and dulcimer – with which light-heeled agit-prop actors or street musicians could run. Implicitly it revisited the ‘appropriate accompaniment’ debate that had occurred during the 1960s. “And tune themselves, quickly,” she adds.

The Paper Stage is the missing link in MacColl and Seeger’s chain of work. It bridges the Bard of Beckenham’s early agit-prop theatre and dramatist past, his love of theatrical history and street-corner minstrelsy. “Ewan loved the Shakespeare plays,” Seeger recalls, “and certain of them he was fascinated by. Titus Andronicus, which is very cruel, for example. He was excited by the theatricality of ballads and the musicality of the speech of Shakespeare. These versions were very singable. That was the thing about them. Very singable. When you look at some of the flowery language that was going on in Elizabethan songs, these stories were almost built like the classic ballads.”

How come The Paper Stage is barely known beyond its title? In Ben Harker’s biography, Class Act – The Cultural And Political Life Of Ewan MacColl (2007) it gets a total of 37 words while MacColl’s own highly selective autobiography Journeyman (1990) makes no mention of the project. There are several possibilities. Many people had developed MacColl and Seeger project fatigue, just as they had the folk cadres’ reviews. There was an awful lot of MacColl and Seeger and it cost an awful lot. Once upon a time, Chorus From The Gallows (1960) about criminals and criminality had lasted one record; at another extreme The Long Harvest ran to ten volumes.

To put it into some sort of financial context, that represented a considerable investment and a great deal of budgeting making a 10-LP set the stuff of public library acquisition. Last, they had to overcome the growing if not prevailing perception that their scholarly inclined, themed work was overly earnest. This reissue provides the first real opportunity to reappraise this project’s importance – or appreciate it for the first time. Do so.

With thanks to Sofi Mogensen at fRoots.

The Paper Stage (CAMSCO 702d, 2008)

Disc 1:

1 The Taming of a Shrew

2 King Lear & His Three Daughters

3 Arden of Faversham

4 The Frolicksome Duke, or The Tinker’s Good Fortune

Disc 2:

5 Titus Andronicus’ Complaint

6 Gerontus, The Jew of Venice

7 The Spanish Tragedy

8 Warning Piece to England

www.pegseeger.com

29. 7. 2009 |

read more...

The golden-throated bird on the Hogarthian wire

[by Ken Hunt, London] Say you woke up one morning and the smell wasn’t coffee but the stench of something having gone off. What would you do? It happened to Leonard Cohen while he was on retreat at the Mount Baldy Zen Center in southern California’s San Gabriel Mountains. With a sheaf of law suits behind him, Cohen’s remedy was to hit the road, drumming up new interest by touring and giving audiences what they wanted. He picked himself up, brushed himself down and started all over again – sensibly chronicling the process with the revenue-injecting CD and DVD Live in London from the O2 venue in London in July 2008.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Say you woke up one morning and the smell wasn’t coffee but the stench of something having gone off. What would you do? It happened to Leonard Cohen while he was on retreat at the Mount Baldy Zen Center in southern California’s San Gabriel Mountains. With a sheaf of law suits behind him, Cohen’s remedy was to hit the road, drumming up new interest by touring and giving audiences what they wanted. He picked himself up, brushed himself down and started all over again – sensibly chronicling the process with the revenue-injecting CD and DVD Live in London from the O2 venue in London in July 2008.

In July 2009 the nearest he got to London was Brooklands, near Weybridge – an outdoor venue on the site of the world’s first purpose-built motor racing circuit. (And being Surrey naturally the overcast skies turned drizzle into rain and, forewarned, forearmed, Neil Larsen’s keyboards were draped by waterproofing throughout – though his Hammond B3 sang out of a security about as pretty, the big screens could not lie, as a reused condom.) At Weybridge, no doubt ‘immortalised’ on mobile phone cameras, during Hallelujah Cohen interjected, “I didn’t come all this way to Weybridge/To fool yer” – though please do re-run the moment on YouTube in case I misheard and he sang ‘weighbridge’. Ad-libbing stage remarks is not his forte yet, however. He delivers the mulled-over, so to speak.

That same month saw him scheduled to give concerts in Cologne, Berlin, Antwerp, Nantes, Paris, Toulouse, Weybridge, Liverpool, Langesund, Molde, Dublin, Belfast, Lisbon and Leon. That is eight countries, not counting that return to the United Kingdom for the Belfast concert. Not bad for a chap born in September 1934.

Throughout the concert two cameras stationed in front of the stage provided the pixels for the big screen on each side of the stage. But a sneaky third did emerge. It was probably most tellingly deployed during the opening song of the second half – Tower of Song – because the camera was in on the joke with its close-ups of Cohen’s right hand tinkling the ivories in unapologetically pedestrian fashion – to great applause. Camera and audience were complicit in the joke. After his ‘spotlit moment’ he gleefully announced, “Thank you music lovers.” To renewed applause. Clearly the band’s keyboardist could have run rings around him but that would have defeated the point of Cohen’s little planned coup de théâtre.

Throughout the concert two cameras stationed in front of the stage provided the pixels for the big screen on each side of the stage. But a sneaky third did emerge. It was probably most tellingly deployed during the opening song of the second half – Tower of Song – because the camera was in on the joke with its close-ups of Cohen’s right hand tinkling the ivories in unapologetically pedestrian fashion – to great applause. Camera and audience were complicit in the joke. After his ‘spotlit moment’ he gleefully announced, “Thank you music lovers.” To renewed applause. Clearly the band’s keyboardist could have run rings around him but that would have defeated the point of Cohen’s little planned coup de théâtre.

Cohen really was the good humour man. His wry lyrical proclivities long ago trounced the slit-your-wrists clichés because so many songs have their drolleries – even Dress Rehearsal Rag (not performed) is a song not without its odd humorous lapse. Too many people buy into the received opinion and ignore the light and shade to concentrate on the darkness. Take that Nirvana In Utero moment and the way Kurt Cobain bought into the cliché with “Give me a Leonard Cohen afterworld/So I can sigh eternally” in Penny Royal Tea. To digress slightly in order to introduce a folkloristic twist to In Utero, in European herblore preparations of polajka – in Czech – or pennyroyal were used to promote menstrual flow or induce abortion. Whereas probably it’s just accident that Cobain inadvertently added an abortifacient twist to in utero, Cohen’s writings work effortlessly on multiple levels. A number of his songs allow and usher in Zen-strength possibilities.

Whether noirist or boulevardier, the lover reflecting on his past adventures or present aches, Cohen proved to be the perfect Hogarthian. Plus he delivered sung poetry with a stand-up comedian’s timing. In his and Sharon Robinson’s In My Secret Life he sang, for instance, “I bite my lip/I buy what I’m told/From the latest hit/To the wisdom of old” and held and elongated old in a way that added wit to word. (Not having heard Live in London beforehand, it was still fresh for me.) During I’m Your Man, the lines “And if you want a doctor/I’ll examine every inch of you” were delivered to arch effect, pure roué theatre, cueing female screams.

Whether noirist or boulevardier, the lover reflecting on his past adventures or present aches, Cohen proved to be the perfect Hogarthian. Plus he delivered sung poetry with a stand-up comedian’s timing. In his and Sharon Robinson’s In My Secret Life he sang, for instance, “I bite my lip/I buy what I’m told/From the latest hit/To the wisdom of old” and held and elongated old in a way that added wit to word. (Not having heard Live in London beforehand, it was still fresh for me.) During I’m Your Man, the lines “And if you want a doctor/I’ll examine every inch of you” were delivered to arch effect, pure roué theatre, cueing female screams.

His songs were littered with self-deprecating observations and wall-eyed philosophical insights. Everybody Knows in the first set with its “Everybody knows that you’ve been faithful/Give or take a night or two” and suchlike was full of barbs and though the songs may be as familiar as hell, seeing him deliver them and raise his hat to the audience afterwards added poignancy. That is what the live moment demands and delivers way beyond the DVD souvenir. Cohen used every ounce of his limitations to deliver a truly superlative performance, praising his accompanists with remarks such as “So very beautiful” after Tower of Song, endearing himself still more for his rapt audience.

Now to get to the heart of the matter, here was a 74 3/4-year-old man who achieved what he did not merely because of the strength of his catalogue but, importantly, because of the power and suppleness of his ensemble under m.d. Roscoe Beck. During The Future – as on Live in London, the second song in the first set (the first seven songs were performed in the same order as that double-CD and DVD) – the voices of Sharon Robinson and The Webb Sisters – and their silky melt of different vocal colours and timbres – lifted the song each time they warbled “Repent” while on Dance Me To The End of Time Javier Mas cleverly conjured a Greek feeling with Spanish instrumentation, summoning a wind from Hydra, Cohen’s Aegean island past out of which so many important early songs took on shape and substance.

The crux of the matter is, the band gives him the freedom to fly and cover his deficiencies brilliantly. For example, during Suzanne the three female singers sang the phrase “with your mind” as a rising harmony that allowed him to trail off and cleverly bury his final note. The arrangements and instrumentation weren’t about recapturing past vinyl glories, they were about getting under the skin of the songs and pouring old wine into crystal decanters – as opposed too many acts’ plastic carry-out or wine box – for today’s delectation.

The crux of the matter is, the band gives him the freedom to fly and cover his deficiencies brilliantly. For example, during Suzanne the three female singers sang the phrase “with your mind” as a rising harmony that allowed him to trail off and cleverly bury his final note. The arrangements and instrumentation weren’t about recapturing past vinyl glories, they were about getting under the skin of the songs and pouring old wine into crystal decanters – as opposed too many acts’ plastic carry-out or wine box – for today’s delectation.

Two songs in, my friend’s sister sitting next to me whispered the wish to adopt Leonard Cohen as her grandfather. I wrote the remark down in my notes, followed by, lapsing into German, “an open invitation to Unzucht.” Unzucht means ‘sexual offence’ in German jurisprudence. Leonard Cohen was that good. He really was. And he definitely still has powers to charm sweet songbirds down from the trees.

Ensemble

Leonard Cohen: vocals, guitar, keyboards

Roscoe Beck: musical director, 5-string electric bass, double-bass, backing vocals

Rafael Gayol: drums, percussion

Neil Larsen: keyboards, accordion

Javier Mas: bandurria, laud, archilaud and 12-string guitar

Bob Metzger: electric and acoustic guitars, pedal steel, vocals

Sharon Robinson: vocals

Dino Soldo: tenor and soprano saxophone, winds, vocals

Charley and Hattie Webb (The Webb Sisters): vocals

Hattie Webb: harp

Set list

First Set* Dance Me To The End Of Love* The Future* Ain’t No Cure For Love* Bird On The Wire* Everybody Knows* In My Secret Life* Who By Fire* Heart With No Companion* Democracy* Anthem

Intermission

Second Set* Tower Of Song* Suzanne* Sisters Of Mercy* The Partisan* Boogie Street* Hallelujah* I’m Your Man* Take This Waltz

Encores

* So Long, Marianne* First We Take Manhattan* Famous Blue Raincoat* If It Be Your Will* Closing Time* I Tried To Leave You* Whither Thou Goest

Apart from the Live in London image, photos (c) Santosh Sidhu/Swing 51 Archives and Ken Hunt/Swing 51 Archives (the Corvus splendens Crow On the Wire image)

More information, videos and sundry guff

http://www.leonardcohen.com/

19. 7. 2009 |

read more...

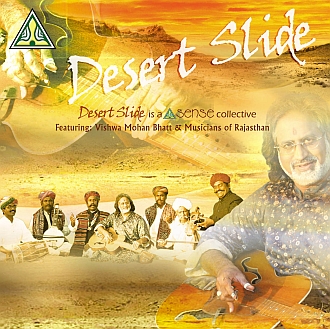

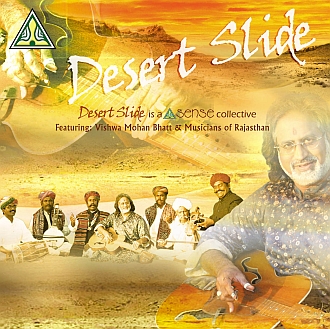

[by Ken Hunt, London] Even by repute, people who have never been to Rajasthan and only ever saw photographs or artwork, view Rajasthan popularly as a region saturated with colour. In its Great Thar Desert, soil, sand and salt lakes offer a palette of yellows, browns and reds. In its deciduous woodlands dhok and dhak – the tree known as the ‘flame of the forest’ – provide the seasonal mosaics of the forest canopy and forest floor and then there is the vibrancy of bougainvillea everywhere whether on the highways or streets. In its street markets full of chillies, mangoes, bananas and spinach, Rajasthan offers an abundance of saturated colours – and watery contrasts. Then factor in whether through raga or folk dance or mela (festival) how musically Rajasthan is affected by what is all around when musicians play.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Even by repute, people who have never been to Rajasthan and only ever saw photographs or artwork, view Rajasthan popularly as a region saturated with colour. In its Great Thar Desert, soil, sand and salt lakes offer a palette of yellows, browns and reds. In its deciduous woodlands dhok and dhak – the tree known as the ‘flame of the forest’ – provide the seasonal mosaics of the forest canopy and forest floor and then there is the vibrancy of bougainvillea everywhere whether on the highways or streets. In its street markets full of chillies, mangoes, bananas and spinach, Rajasthan offers an abundance of saturated colours – and watery contrasts. Then factor in whether through raga or folk dance or mela (festival) how musically Rajasthan is affected by what is all around when musicians play.

An ornithological metaphor springs to mind when it comes to Rajasthan’s traditional music. Jaipur has been home for demoiselle cranes for time out of mind. Huge numbers hug the thermals over the Pink City (Jaipur), landing to strut their courtship and territorial stuff – a source of inspiration for Rajasthani dance. Yet Keoladeo, long the place where Siberian cranes overwintered, has seen the birds’ numbers decrease to next to nothing. What is increasingly happening in Rajasthan – without getting judgemental about the musicians, performers and dancers – is tradition is disappearing in the tourist heat haze. There is a buzz that folk culture is getting as defanged as the palaces’ dancing cobras.

The Desert Slide project bucks any such prevailing trends. A dynamic microcosm, it cross-fertilises two parallel yet different Rajasthani traditions. One is the world of Hindustani classicism that Mohan Vishwa Bhatt playing the Vishwa Mohan vina represents. The other brings together Rajasthan’s two main indigenous and hereditary clans of semi-professional or full-time professional music-makers, namely the Langas and Manganiars (or Manganihars). That commingling of traditions is interesting because it brings together hereditary Hindu and Muslim musicians to common purpose. As a concert and recording collaboration, Desert Slide represents something boldly different in Rajasthani music.

The opening song Helo mharo suno on Desert Slide reinforces the conjoining of traditions. It is a praise song for Baba Ramdev, who was soon revered both as a Hindu deity and an Islamic pir (saint) in Rajasthan. In many ways what is more interesting still than Baba Ramdev crossing that religious divide is him spanning the gulf of caste.

Desert Slide is designed to grab your attention and is the very personification of how musicians embrace vocal and instrumental folk and art music traditions – that business of music connecting rather than dividing.

Let’s dig deeper.

The opening devotional song Helo mharo suno (track 1) is kin to the bhajan form of Hindu hymnody. It is in praise of one of Rajasthan’s most revered Hindu deities and Islamic pirs (saints) of medieval times. Said to have lived from 1469 to 1575 in the Christian Era, Baba Ramdev is linked with the Pokaran district, some 110 km east of Jelsalmer in western Rajasthan and is often depicted on horseback. His worship crosses the Hindu-Muslim divide as well as crossing the caste line since his followers include caste Hindus and the casteless (Dalits or Untouchables) in modern-day Rajasthan and Gujarat – and even further afield into Madhya Pradesh and Sind on the Pakistani side of the border. Several Rajasthani melas (fairs or festivals) celebrate his memory. Helo mharo suno is rooted in râg Bageshri with a sprinkle of râg Shahana and appears in an 8-beat tâl (rhythm cycle). Its title can be rendered along the lines of ‘Hear me calling you’ or ‘Hear my entreaty’. The style of singing is designed to attract attention. And it works remarkably well.

Avalu thari aave, badilo ghar aave (track 2) is a song of separation, a woman’s plea to her beloved (badilo), asking him to come home (ghar). Vishwa Mohan Bhatt plays a theme, a rhythmic melodic hook of his own composition early in the piece to convey a sense of journeying, but the wit of his playing lies in slipping between the interstices of ‘ragadom’. The interpretation is based in râg Bhairav with a little trace of Kalingra, another morning râg, again in the same 8-beat tâl, keherwa or kaharwa as Helo mharo suno. The portrait painted uses filigree brushstrokes, impressionistically summoning the two râgs’ slight difference.

Avalu thari aave, badilo ghar aave (track 2) is a song of separation, a woman’s plea to her beloved (badilo), asking him to come home (ghar). Vishwa Mohan Bhatt plays a theme, a rhythmic melodic hook of his own composition early in the piece to convey a sense of journeying, but the wit of his playing lies in slipping between the interstices of ‘ragadom’. The interpretation is based in râg Bhairav with a little trace of Kalingra, another morning râg, again in the same 8-beat tâl, keherwa or kaharwa as Helo mharo suno. The portrait painted uses filigree brushstrokes, impressionistically summoning the two râgs’ slight difference.

Jhilmil barse meh (track 3) is a rainy season song. In Rajasthani ‘meh’ means rain, a word perhaps related to the Hindi ‘megh’ (cloud) – hence the monsoon season râg Megh. ‘Barse’ means ‘pouring’ in this context while ‘jhilmil’ indicates something tiny or small, so the line can be translated as ‘Droplets of rain are falling’. The song is based in Malhar, a monsoon season râg, and Des, a râg with a Malhar feel. It is, so to speak, Des with a wash of Malhar – as distinct from Des Malhar, another râg permutation. Again, like all the pieces on Desert Slide bar Kesariya balam, it is in keherwa – that 8-beat tâl.

All languages love onomatopoeia. Rajasthani is no exception. In track 4, Hichki (Hiccoughs) hinges on a local folk belief or superstition. When a person thinks of somebody from whom they are apart, the person he or she is missing is said to get the hiccups. The narrator has got the hiccups. In Rajasthan the râg it is set in is commonly called Bhairavi but it is actually truer to Kirvani, a râg originally associated with the South Indian heartland. Vishwa Mohan Bhatt’s alap or opening invocation is designed to set the mood or scene, creating an atmosphere suffused with sadness or melancholy and a pain and pangs of separation. It also has a romantic undertow strong enough to whip the listener off their feet.

All languages love onomatopoeia. Rajasthani is no exception. In track 4, Hichki (Hiccoughs) hinges on a local folk belief or superstition. When a person thinks of somebody from whom they are apart, the person he or she is missing is said to get the hiccups. The narrator has got the hiccups. In Rajasthan the râg it is set in is commonly called Bhairavi but it is actually truer to Kirvani, a râg originally associated with the South Indian heartland. Vishwa Mohan Bhatt’s alap or opening invocation is designed to set the mood or scene, creating an atmosphere suffused with sadness or melancholy and a pain and pangs of separation. It also has a romantic undertow strong enough to whip the listener off their feet.

Mhari menhdi ro rang (track5) (The colour of my henna) is set in Pahadi. Pahadi here is more like a dhun or folk air than a pure râg. Distinguishing it from a strict râg, Bhatt likes to dub it a “dhun Pahadi” – a folk air Pahadi. The programme’s instinctive mela sub-theme resurfaces here. In Rajasthan, but also elsewhere in the Indian subcontinent, menhdi or henna’s uses range from the cosmetic – it is a hair colorant used by men and women alike – to rites of passage. It is particularly associated with bridal adornment and is used to dye intricate patterns on celebrants’ hands. Henna is also associated with typically Rajasthani melas. One such is the monsoon-season Teej, the festival of swings, in the Hindu month of Shravana (August-time in the Christian calendar) which toasts Parvati’s union with Shiva and hence conjugal bliss. Another is Gangaur, Rajasthan’s defining 18-day mela that follows on the heels of Holi, the spring festival of colours, and a mela that, like Teej, is connected with the Goddess Parvati. Henna’s earthy browns and reds are the colours from which life – and symbolically, green – springs.

Kesariya balam (track 6) or Saffron Beloved – imagine the colour of kesar mangos – is another song of longing and separation. It is in the 6-beat dadra tâl and set in Mand, a râg borrowed from the folk music of Rajasthan. The lyrics welcome the listener to the person’s home or homeland. The singer sings of counting the days, counting off the days that they have been apart, on the finger joints of the outstretched palm. She has done this so frequently and for so long that the lines of the skin creases are wearing away.

Rajasthan’s vastness of bright light and vibrant colour is reflected in its folk arts and the land’s robust musical heritage. That intensity and the sheer size of the state determine that it is a land of extremes. It embraces the camel browns and kesar yellows of the Thar Desert on its western flank and – pointing east towards Uttar Pradesh – the grey plumage and black heads of demoiselle cranes soaring over the Pink City, descending to dance and inspire dancers.

Desert Slide reflects the excitement of its birthplace, its surroundings, its musical origins and the colours of Rajasthan. In its bridging of tradition, nothing like Desert Slide has ever been captured for posterity before and that is why Helo mharo suno in its invocation of Baba Ramdev is so perfect. He banished boundaries in Rajasthan. Maybe only a white writer would have dared make those connections.

(c) 2009 Ken Hunt and Vishwa Mohan Bhatt – http://www.vishwamohanbhatt.com/

Photographs Desert Slide (c) Sense World Music 2009, otherwise (c) 2009 Ken Hunt

Desert Slide Sense World Music 085 (2006)

6. 7. 2009 |

read more...

« Later articles

Older articles »

[by Ken Hunt, London] The US record producer, engineer and mixer Greg Ladanyi, who worked with, amongst others, Jackson Browne, Fleetwood Mac, Jeff Healey, Don Henley, Los Jaguares, David Lindley and Warren Zevon, died on Cyprus on 29 September 2009. He died of the consequence of an accident on stage whilst touring with the Greek Cypriot singer Anna Vissi whose album Apagorevmeno (2008) he had co-produced.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The US record producer, engineer and mixer Greg Ladanyi, who worked with, amongst others, Jackson Browne, Fleetwood Mac, Jeff Healey, Don Henley, Los Jaguares, David Lindley and Warren Zevon, died on Cyprus on 29 September 2009. He died of the consequence of an accident on stage whilst touring with the Greek Cypriot singer Anna Vissi whose album Apagorevmeno (2008) he had co-produced. Karanfil Se Na Put Sprema – Amira Medunjanin and Merima Ključo

Karanfil Se Na Put Sprema – Amira Medunjanin and Merima Ključo Mindenkinek Kurványja – Bea Palya

Mindenkinek Kurványja – Bea Palya Troubadour – Tim Buckley

Troubadour – Tim Buckley David Crosby – Cowboy Movie

David Crosby – Cowboy Movie  [by Ken Hunt, London] Neil Young once stated, “The great Canadian dream is to get out.” It was certainly what three fifths of Buffalo Springfield did when they joined the California-based rock group’s US contingent, Stephen Stills and Richie Furay. In 1966 Young and Bruce Palmer – the band’s original bassist – had headed south in a 1953 Pontiac hearse with Ontario plates. Minds set on forming a rock group and already working up Young’s Nowadays Clancy Can’t Even Sing, Furay and Stills famously spotted the Canadians driving in the opposite direction on Sunset Boulevard. (Stills had already met Young in Thunder Bay, Ontario and had been taken.) Furay executed some nifty pursuit-chase driving and caught up with them before they hit the highway to head home. Four fifths of Buffalo Springfield were in place.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Neil Young once stated, “The great Canadian dream is to get out.” It was certainly what three fifths of Buffalo Springfield did when they joined the California-based rock group’s US contingent, Stephen Stills and Richie Furay. In 1966 Young and Bruce Palmer – the band’s original bassist – had headed south in a 1953 Pontiac hearse with Ontario plates. Minds set on forming a rock group and already working up Young’s Nowadays Clancy Can’t Even Sing, Furay and Stills famously spotted the Canadians driving in the opposite direction on Sunset Boulevard. (Stills had already met Young in Thunder Bay, Ontario and had been taken.) Furay executed some nifty pursuit-chase driving and caught up with them before they hit the highway to head home. Four fifths of Buffalo Springfield were in place. Dewey Martin completed the line-up in April 1966. It was widely believed he was American too. In fact he had been born Walter Milton Dewayne Midkiff in Chesterfield, Ontario on 30 September 1940 – ‘Dewey’ was a longstanding nickname and Midkiff was a mouthful – and grew up in Ottawa. He had already embraced the Great Canadian Dream and emigrated to the States. After US national service, he fetched up in Nashville at the beginning of the 1960s. He strove to break into its country scene, drumming on sessions and in touring bands. By 1963 he was playing with Faron Young and when the tour got to Los Angeles he liked the place so much he stayed. On the West Coast he played with Sir Raleigh and the Coupons (another of those bogus British Invasion groups), The Sons of Adam, the Modern Folk Quartet, the Standells and the Dillards.

Dewey Martin completed the line-up in April 1966. It was widely believed he was American too. In fact he had been born Walter Milton Dewayne Midkiff in Chesterfield, Ontario on 30 September 1940 – ‘Dewey’ was a longstanding nickname and Midkiff was a mouthful – and grew up in Ottawa. He had already embraced the Great Canadian Dream and emigrated to the States. After US national service, he fetched up in Nashville at the beginning of the 1960s. He strove to break into its country scene, drumming on sessions and in touring bands. By 1963 he was playing with Faron Young and when the tour got to Los Angeles he liked the place so much he stayed. On the West Coast he played with Sir Raleigh and the Coupons (another of those bogus British Invasion groups), The Sons of Adam, the Modern Folk Quartet, the Standells and the Dillards. Buffalo Springfield (1966) and Buffalo Springfield (1967) – originally with the working title Stampede – were the only true albums released during their lifespan. By May 1968 they had imploded and Last Time Around (1968) was a sellotaped-together, contractual obligation affair.

Buffalo Springfield (1966) and Buffalo Springfield (1967) – originally with the working title Stampede – were the only true albums released during their lifespan. By May 1968 they had imploded and Last Time Around (1968) was a sellotaped-together, contractual obligation affair. Wild Man In The City – Manu Dibango

Wild Man In The City – Manu Dibango Drown In My Own Tears – Ray Charles

Drown In My Own Tears – Ray Charles I Was Born To Preach The Gospel – Washington Phillips

I Was Born To Preach The Gospel – Washington Phillips Don’t Tempt Me – Richard Thompson

Don’t Tempt Me – Richard Thompson Eight Miles High – The Byrds

Eight Miles High – The Byrds Even A Dog Can Shake Hands – Warren Zevon

Even A Dog Can Shake Hands – Warren Zevon [by Ken Hunt, London] The Dutch counter-culture poet, writer and painter Simon Vinkenoog died in Amsterdam on Saturday, 12 July 2009, a few days before his 81st birthday. Born on 18 July 1928 in Amsterdam, Vinkenoog was the child of a lone parent family raised in the De Pijp part of Amsterdam’s Oud-Zuid (Old South) district.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Dutch counter-culture poet, writer and painter Simon Vinkenoog died in Amsterdam on Saturday, 12 July 2009, a few days before his 81st birthday. Born on 18 July 1928 in Amsterdam, Vinkenoog was the child of a lone parent family raised in the De Pijp part of Amsterdam’s Oud-Zuid (Old South) district. [by Ken Hunt, London] Forty years or so ago, Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger released their most recondite project, the two-volume Paper Stage. It was reconstructions of the first Elizabethan Age’s theatre for the second Elizabethan Age. The original peddlers of these more unauthorised than guerrilla playlets in song left few traces and fewer fingerprints. All that survived was the printed page. Theirs was street theatre, the equivalent of graffiti artist Banksy’s Mona Lisa with a rocket launcher, or that Banksy rat sawing a getaway hole to freedom through the pavement. Without forcing the analogy, the Paper Stage material somehow survived on paper without the accompanying music, just as Banksy’s long-gone, ephemeral spray paintings and stencil art images survive as photographic images in the book Wall And Piece without the walls.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Forty years or so ago, Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger released their most recondite project, the two-volume Paper Stage. It was reconstructions of the first Elizabethan Age’s theatre for the second Elizabethan Age. The original peddlers of these more unauthorised than guerrilla playlets in song left few traces and fewer fingerprints. All that survived was the printed page. Theirs was street theatre, the equivalent of graffiti artist Banksy’s Mona Lisa with a rocket launcher, or that Banksy rat sawing a getaway hole to freedom through the pavement. Without forcing the analogy, the Paper Stage material somehow survived on paper without the accompanying music, just as Banksy’s long-gone, ephemeral spray paintings and stencil art images survive as photographic images in the book Wall And Piece without the walls. [by Ken Hunt, London] Say you woke up one morning and the smell wasn’t coffee but the stench of something having gone off. What would you do? It happened to Leonard Cohen while he was on retreat at the Mount Baldy Zen Center in southern California’s San Gabriel Mountains. With a sheaf of law suits behind him, Cohen’s remedy was to hit the road, drumming up new interest by touring and giving audiences what they wanted. He picked himself up, brushed himself down and started all over again – sensibly chronicling the process with the revenue-injecting CD and DVD Live in London from the O2 venue in London in July 2008.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Say you woke up one morning and the smell wasn’t coffee but the stench of something having gone off. What would you do? It happened to Leonard Cohen while he was on retreat at the Mount Baldy Zen Center in southern California’s San Gabriel Mountains. With a sheaf of law suits behind him, Cohen’s remedy was to hit the road, drumming up new interest by touring and giving audiences what they wanted. He picked himself up, brushed himself down and started all over again – sensibly chronicling the process with the revenue-injecting CD and DVD Live in London from the O2 venue in London in July 2008. Throughout the concert two cameras stationed in front of the stage provided the pixels for the big screen on each side of the stage. But a sneaky third did emerge. It was probably most tellingly deployed during the opening song of the second half – Tower of Song – because the camera was in on the joke with its close-ups of Cohen’s right hand tinkling the ivories in unapologetically pedestrian fashion – to great applause. Camera and audience were complicit in the joke. After his ‘spotlit moment’ he gleefully announced, “Thank you music lovers.” To renewed applause. Clearly the band’s keyboardist could have run rings around him but that would have defeated the point of Cohen’s little planned coup de théâtre.

Throughout the concert two cameras stationed in front of the stage provided the pixels for the big screen on each side of the stage. But a sneaky third did emerge. It was probably most tellingly deployed during the opening song of the second half – Tower of Song – because the camera was in on the joke with its close-ups of Cohen’s right hand tinkling the ivories in unapologetically pedestrian fashion – to great applause. Camera and audience were complicit in the joke. After his ‘spotlit moment’ he gleefully announced, “Thank you music lovers.” To renewed applause. Clearly the band’s keyboardist could have run rings around him but that would have defeated the point of Cohen’s little planned coup de théâtre. Whether noirist or boulevardier, the lover reflecting on his past adventures or present aches, Cohen proved to be the perfect Hogarthian. Plus he delivered sung poetry with a stand-up comedian’s timing. In his and Sharon Robinson’s In My Secret Life he sang, for instance, “I bite my lip/I buy what I’m told/From the latest hit/To the wisdom of old” and held and elongated old in a way that added wit to word. (Not having heard Live in London beforehand, it was still fresh for me.) During I’m Your Man, the lines “And if you want a doctor/I’ll examine every inch of you” were delivered to arch effect, pure roué theatre, cueing female screams.

Whether noirist or boulevardier, the lover reflecting on his past adventures or present aches, Cohen proved to be the perfect Hogarthian. Plus he delivered sung poetry with a stand-up comedian’s timing. In his and Sharon Robinson’s In My Secret Life he sang, for instance, “I bite my lip/I buy what I’m told/From the latest hit/To the wisdom of old” and held and elongated old in a way that added wit to word. (Not having heard Live in London beforehand, it was still fresh for me.) During I’m Your Man, the lines “And if you want a doctor/I’ll examine every inch of you” were delivered to arch effect, pure roué theatre, cueing female screams. The crux of the matter is, the band gives him the freedom to fly and cover his deficiencies brilliantly. For example, during Suzanne the three female singers sang the phrase “with your mind” as a rising harmony that allowed him to trail off and cleverly bury his final note. The arrangements and instrumentation weren’t about recapturing past vinyl glories, they were about getting under the skin of the songs and pouring old wine into crystal decanters – as opposed too many acts’ plastic carry-out or wine box – for today’s delectation.

The crux of the matter is, the band gives him the freedom to fly and cover his deficiencies brilliantly. For example, during Suzanne the three female singers sang the phrase “with your mind” as a rising harmony that allowed him to trail off and cleverly bury his final note. The arrangements and instrumentation weren’t about recapturing past vinyl glories, they were about getting under the skin of the songs and pouring old wine into crystal decanters – as opposed too many acts’ plastic carry-out or wine box – for today’s delectation. [by Ken Hunt, London] Even by repute, people who have never been to Rajasthan and only ever saw photographs or artwork, view Rajasthan popularly as a region saturated with colour. In its Great Thar Desert, soil, sand and salt lakes offer a palette of yellows, browns and reds. In its deciduous woodlands dhok and dhak – the tree known as the ‘flame of the forest’ – provide the seasonal mosaics of the forest canopy and forest floor and then there is the vibrancy of bougainvillea everywhere whether on the highways or streets. In its street markets full of chillies, mangoes, bananas and spinach, Rajasthan offers an abundance of saturated colours – and watery contrasts. Then factor in whether through raga or folk dance or mela (festival) how musically Rajasthan is affected by what is all around when musicians play.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Even by repute, people who have never been to Rajasthan and only ever saw photographs or artwork, view Rajasthan popularly as a region saturated with colour. In its Great Thar Desert, soil, sand and salt lakes offer a palette of yellows, browns and reds. In its deciduous woodlands dhok and dhak – the tree known as the ‘flame of the forest’ – provide the seasonal mosaics of the forest canopy and forest floor and then there is the vibrancy of bougainvillea everywhere whether on the highways or streets. In its street markets full of chillies, mangoes, bananas and spinach, Rajasthan offers an abundance of saturated colours – and watery contrasts. Then factor in whether through raga or folk dance or mela (festival) how musically Rajasthan is affected by what is all around when musicians play. Avalu thari aave, badilo ghar aave (track 2) is a song of separation, a woman’s plea to her beloved (badilo), asking him to come home (ghar). Vishwa Mohan Bhatt plays a theme, a rhythmic melodic hook of his own composition early in the piece to convey a sense of journeying, but the wit of his playing lies in slipping between the interstices of ‘ragadom’. The interpretation is based in râg Bhairav with a little trace of Kalingra, another morning râg, again in the same 8-beat tâl, keherwa or kaharwa as Helo mharo suno. The portrait painted uses filigree brushstrokes, impressionistically summoning the two râgs’ slight difference.

Avalu thari aave, badilo ghar aave (track 2) is a song of separation, a woman’s plea to her beloved (badilo), asking him to come home (ghar). Vishwa Mohan Bhatt plays a theme, a rhythmic melodic hook of his own composition early in the piece to convey a sense of journeying, but the wit of his playing lies in slipping between the interstices of ‘ragadom’. The interpretation is based in râg Bhairav with a little trace of Kalingra, another morning râg, again in the same 8-beat tâl, keherwa or kaharwa as Helo mharo suno. The portrait painted uses filigree brushstrokes, impressionistically summoning the two râgs’ slight difference. All languages love onomatopoeia. Rajasthani is no exception. In track 4, Hichki (Hiccoughs) hinges on a local folk belief or superstition. When a person thinks of somebody from whom they are apart, the person he or she is missing is said to get the hiccups. The narrator has got the hiccups. In Rajasthan the râg it is set in is commonly called Bhairavi but it is actually truer to Kirvani, a râg originally associated with the South Indian heartland. Vishwa Mohan Bhatt’s alap or opening invocation is designed to set the mood or scene, creating an atmosphere suffused with sadness or melancholy and a pain and pangs of separation. It also has a romantic undertow strong enough to whip the listener off their feet.

All languages love onomatopoeia. Rajasthani is no exception. In track 4, Hichki (Hiccoughs) hinges on a local folk belief or superstition. When a person thinks of somebody from whom they are apart, the person he or she is missing is said to get the hiccups. The narrator has got the hiccups. In Rajasthan the râg it is set in is commonly called Bhairavi but it is actually truer to Kirvani, a râg originally associated with the South Indian heartland. Vishwa Mohan Bhatt’s alap or opening invocation is designed to set the mood or scene, creating an atmosphere suffused with sadness or melancholy and a pain and pangs of separation. It also has a romantic undertow strong enough to whip the listener off their feet.