Giant Donut Discs® – November 2009

2. 11. 2009 | Rubriky: Articles,Giant Donut Discs

Most months’ choices reflect deadlines and commissions with a pinch of music for pleasure. This month’s choices are Wenzel & Band, Martin Carthy, Javed Bashir, Sophie Harris and Ian Belton, Carol Grimes, Bob Dylan, Wasifuddin Dagar and Bahauddin Dagar, Alistair Anderson, Kaushiki Chakrabarty and Jackson Browne. As ever, they are in no particular order. Their only link is that none of them would go away. This month’s selections deliberately sidestep the Best of 2009 polls, even though it is that time of the year for such musings for December and January titles.

Zeit der Irren und Idioten – Wenzel & Band

Some of the times I have been happiest in my life have been when music has lifted me up and carried me off. One of those occasions was seeing Hans-Eckardt Wenzel & Band perform on the castle stage at Tanz&FolkFest Rudolstadt in July 2003. It was an altogether magnificent festival with performances by Les Charbonniers de l’enfer, Yggdrasil (the one from the Faroe Islands, at that point fronted by Eivor Pálsdóttir), Blowzabella and the Original Öberkreutzberger Nasenflötenorchester amongst others. Wenzel sang this song there in a set that trounced superlatives.

Some of the times I have been happiest in my life have been when music has lifted me up and carried me off. One of those occasions was seeing Hans-Eckardt Wenzel & Band perform on the castle stage at Tanz&FolkFest Rudolstadt in July 2003. It was an altogether magnificent festival with performances by Les Charbonniers de l’enfer, Yggdrasil (the one from the Faroe Islands, at that point fronted by Eivor Pálsdóttir), Blowzabella and the Original Öberkreutzberger Nasenflötenorchester amongst others. Wenzel sang this song there in a set that trounced superlatives.

Any song with a title that translates as “the time of madmen/mad ones and idiots” is going to pique my interest. Zeit der Irren und Idioten is a flicker-book of vignettes of Berlin city life. Well, when he sings it the backdrop for me is always Berlin. Summer in the city in Berlin is when the tarmac melts and bubbles, the heat is paid back with dives into dives for Bierpausen (‘beer breaks’) and the streets shimmer in the afternoon heat haze.

Wenzel’s take on the city is heated, too. As the verbal images pour out, the tempo builds and builds. Even without knowing German, the song’s frenetic pace communicates a sense of what is going on lyrically. Jan Hermerschmidt’s post-klezmer clarinet and Olli Becker’s drumming will do for you whatever language you speak.

But let’s return to Wenzel, that songwriter of extraordinary clarity and exquisite ambiguity. The first image of summer in the city that hits you is that the Nutten (prostitutes) have been given the time off for good behaviour because it’s too hot for bad behaviour. The word Hitzefrei is an old German workplace and school expression, for knocking off when it gets too hot to work. The police are cleaning their car windows and all logic gets forbidden. From Grünes Licht (Conträr 25, 2001)

Never The Same – Martin Carthy

The arranger-composer, conductor and keyboardist Robert Kirby’s death on 3 October 2009 prompted a revisiting of his work. He is best known for his sessions with Nick Drake – Drake’s first two albums, Five Leaves Left (1969) and Bryter Layter (1970), the ones that broke Kirby’s name. Then came, to give a flavour, Bernie Taupin (Bernie Taupin, 1970), Shelagh McDonald (Stargazer, 1971), Elton John (Madman Across The Water, 1971), John Cale (Helen of Troy, 1975), Elvis Costello (Almost Blue, 1982) through to Paul Weller (Heliocentric, 2000), The Magic Numbers (Those The Brokes, 2006) and Linda Thompson (Versatile Heart, 2007). All in all, a remarkable body of work.

Two works of his stand haloed for me: his conducting on David Ackles’ masterpiece American Gothic (1972) and arranging on Shining Bright (2002). The last one is a jewel of England’s Folk Revival – a revisiting of the songs of Lal and her brother Mike Waterson.

The only time I met Robert Kirby was when I dropped Martin Carthy off at the studio to cut this song of Lal Waterson’s. The Wrecking Crew – Howard Gott (violin), Jackie Norrie (violin), Sophie Sirota (viola) and Andy Waterworth (double bass) and Sarah Willson (cello) – were tuning and limbering up fingers by practising figures from Kirby’s arrangement. I didn’t stick around for the session to begin. Studios aren’t a spectator sport. Carthy’s treatment of his sister-in-law’s song is spot-on. From Shining Bright (Topic TSCD519, 2002)

Ken Hunt’s obituary of Robert Kirby from The Scotsman of 8 October 2009: http://news.scotsman.com/obituaries/Robert-Kirby.5714091.jp

Pierre Perrone’s excellent obituary published in The Independent of 30 October 2009 is here: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/robert-kirby-musical -arranger-who-worked-with-nick-drake-and-elvis-costello-1811607.h tml

Aj Latha Naeeo – Javed Bashir

The wonders of the new-fangled internet threw up this Pakistani “Amalgam of Sufi & Modern Music”. Bashir is a member of the Mekaal Hasan Band. The combination of vocals and drumming is just astonishing. Watch and be stunned.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IZCkA4HpRn4

Spiegel im Spiegel – Sophie Harris and Ian Belton

The initial draw of the Out of the Darkness album was Julian Marshall’s setting of the poem Aus dem Dunkel (Out of the Darkness). Gertrud Käthe Chodziesner (1894-1943) went under the nom de plume of Gertrud Kolmar. She is a transformative poet. For example, her seashore poem Travemünde – set in the Schleswig-Holstein port of Travemünde, near Lübeck – is a series of springboards into what can fairly be described as the infinite, with its images of the sounds and smells and colours of the natural world. Hibernating bats and seaweed hair have seldom been deployed so poetically and memorably – and probably never together in the same poem.

But good intentions often go astray and instead of Aus dem Dunkel it was Arvo Pärt’s Spiegel im Spiegel that wound up on replay. Its title can be translated variously. The better translation is ‘Mirrors in the mirror’ (over ‘Mirror in the mirror’) with its conjuring of never-ending mirrored images. This particular Spiegel im Spiegel is a setting for piano and cello, respectively the husband and wife duo of Ian Belton and Sophie Harris. Their performance reaches out. It needs no more words. Sheer beauty. From Out of the Darkness (Music & Media MMC101, 2009)

Into My Arms – Carol Grimes

Down the years certain songs have slipped under my guard and lodged themselves in my cranium before I realised what was going on. Tom Waits’ Innocent When You Dream is one. This is another. Nick Cave’s version is on Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds’ The Boatman’s Call (1997) and The Best of Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds (1998). Its first line grabs the attention: “I don’t believe in an interventionist God.”

Carol Grimes’ interpretation reaches all the parts the song should. The way she rolls the words round her mouth, accompanied by Greg Wain’s sparse acoustic guitar, is exquisite. “And I don’t believe in the existence of angels/But looking at you I wonder if that’s true.” She pulls you towards her, not like some infatuated lover, more like someone who knows you inside-out and still loves you. From Mother (CG59, 2005)

http://www.carolgrimes.com/

http://www.myspace.com/iamcarolgrimes

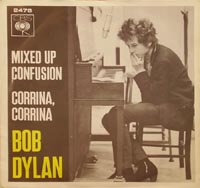

Mixed-Up Confusion – Bob Dylan

In the between-the-decades decade of the mid 1960s to the mid 1970s, Amsterdam exerted a remarkable pulling power. For me and countless thousands of hitchers. Hitch-hiking was an accepted and, for the most part, safe way of seeing Europe. Amsterdam was one of the cities many people bee-lined towards. It had plentiful counter-culture and alternative lifestyle attractions – more accurately, liestyle attractions for summer bohemians destined to conform and blend into grey. It had a city council-run hostel that, like The Dam – the square a short stroll from the main railway, tram and bus terminus – became a rendezvous for travellers of the kind that travelled by thumb. Amsterdam’s superb Indonesian food and music were also attractions, especially if on the homeward stretch from Scandinavia or Berlin or Austria.

In the between-the-decades decade of the mid 1960s to the mid 1970s, Amsterdam exerted a remarkable pulling power. For me and countless thousands of hitchers. Hitch-hiking was an accepted and, for the most part, safe way of seeing Europe. Amsterdam was one of the cities many people bee-lined towards. It had plentiful counter-culture and alternative lifestyle attractions – more accurately, liestyle attractions for summer bohemians destined to conform and blend into grey. It had a city council-run hostel that, like The Dam – the square a short stroll from the main railway, tram and bus terminus – became a rendezvous for travellers of the kind that travelled by thumb. Amsterdam’s superb Indonesian food and music were also attractions, especially if on the homeward stretch from Scandinavia or Berlin or Austria.

You see, the Dutch had a reputation for picking up on all manner of overlooked, good music, underground literature (of the banned kind) and comics. Dutch record companies were putting out interesting stuff on domestic release and Amsterdam’s record shops were bringing in US imports barely seen in Britain. The 45 single of Mixed-Up Confusion b/w Corrina, Corrina (CBS 2476) first appeared in the Netherlands in 1966. (Apparently an earlier US single version had been withdrawn.) The back of this 45’s paper sleeve said CBS Benelux. Hence alongside the picture sleeves for, amongst others, Gene Pitney’s Nobody Needs Your Love, Simon & Garfunkel’s Flowers Never Bend With The Rainfall, The Byrds’ Captain Soul, Ray Conniff’s Somewhere My Love were Bernd Spier’s Der neue Tag beginnt and The Louis Van Dyke Trio’s Shaffy-Cantate. By the early 1970s I had a circle of Dutch friends in Amsterdam and an admiration of Dutch culture and tradition undiminished to the present day.

But I am going off on a tangent. In the grand tradition of Dylan’s work, Mixed-Up Confusion had been shunted into the sidings and didn’t make the next album. It wouldn’t have fit on Freewheelin’ (1963). That is not to say that it was in the same league as his Blind Willie McTell that he left off Infidels so cavalierly. Mixed-Up Confusion is hardly a career highlight yet he carries off the song with a swagger. It was a minor revelation with him brazenly rockin’ out, given that it was cut at the time of the Freewheelin’ sessions. It was cut on 14 November 1962, it says in the Biograph booklet notes. Mixed-Up Confusion even had an alternative take of one of Corrina, Corinna on the B-side.

Aside from its rockabilly drive, Mixed-Up Confusion has a truly atmospheric opening. (Rockabilly would definitely not have been in my vocabulary in the 1960s.) He opens the song unaccompanied with “I’ve got mixed-up confusion/ Man, an’ it’s a-killin’ me” before the band jumps in. But that solo vocal track added an insight into the recording process that had never consciously registered before. It had the sound of air as well. It would be many years before I heard anyone articulate that. It’s a bit like the sort of insight into the recording process in a Jeremy Marre Classic Albums documentary such as Anthem to Beauty or The Band when somebody fades out the other tracks on the mixing desk in order to home in on one track in the mix. From CBS 2476 and Biograph (Columbia COL 488099, 1985)

Malkauns – Wasifuddin Dagar and Bahauddin Dagar

This voice and rudra vina jugalbandi (duet) was recorded at the 2006 Saptak Festival in Ahmedabad in Gujarat in India. The dhrupad singer Wasifuddin Dagar is the twentieth generation of his family to follow The Path (which is what Dagar means). Bahauddin Dagar is part of the same bloodlines and again the twentieth generation. In his case he is the son of Zia Mohiuddin Dagar whose dhrupad artistry was realised instrumentally, like his son’s, by playing the rudra vina.

This voice and rudra vina jugalbandi (duet) was recorded at the 2006 Saptak Festival in Ahmedabad in Gujarat in India. The dhrupad singer Wasifuddin Dagar is the twentieth generation of his family to follow The Path (which is what Dagar means). Bahauddin Dagar is part of the same bloodlines and again the twentieth generation. In his case he is the son of Zia Mohiuddin Dagar whose dhrupad artistry was realised instrumentally, like his son’s, by playing the rudra vina.

Dhrupad is one of the oldest classical music genres of Hindustani music. Some say it is a development from a song genre known as carya giti, a pan-Hindustan classical sonnet-like form also set in ragas, which has been dated to the Ninth to Twelfth Centuries of the Christian Era. It is venerable. Dhrupad has no truck with the flash-bang-wallop, oh-what-a-picture! of the latter, more popular khyal form. It takes its time. If it were food it would be slow food, like the north-eastern Italian dishes made of sweet chestnut flour, flour produced after 40 days and 40 nights of low-heat roasting. This is not to suggest that dhrupad requires an immersion of 40 days and 40 nights. It is not suited to listeners with short attention spans. Like several Asian art music forms, dhrupad is slow-fuse music and, like much in the South Asian cultural heritage, it blurs Indo-Pakistani and Hindu-Muslim divisions. Even though they are Muslim, they are caretakers of a Hindu musical tradition of utmost profundity,

The set time for Malkauns are the hours leading up to midnight until around one in the new day. This one-raga performance over a two-volume set is like a reverie, a dreamscape. Words, as is usual in dhrupad, are broken down into syllables, presented and re-presented, all the while, in a steadily evolving fashion. Wasifuddin Dagar and Bahauddin Dagar’s interpretation is full of flourishes of cut-crystal clarity and improvised daring. Its alap – the unmetered opening movement – feels timeless in multiple senses. Certainly it robs the listener of any sense of time in its tick-tock manifestation. It creates an awareness that time must be passing only in a Dali-like melting watch kind of way. It is only on the second disc that percussion enters, with Pravin Kumar Arya playing the double-headed, barrel hand-drum pakhawaj. Laurence Bastit plays tanpura throughout. Disc 1 is the one. From Vedanta (Sense World Music 094, 2007)

For more information about Wasifuddin Dagar, Bahauddin Mohiuddin Dagar and the Dagarvani tradition go to, http://dagarvani.org/

http://www.senseworldmusic.com/

The Air For Maurice Ogg/Jumping Jack/ The Air For Maurice Ogg – Alistair Anderson

To my mind, the disappearance of Ali Anderson’s magnum opus, the Steel Skies suite from the Topic catalogue until 2009 was the label’s single greatest loss. It originally appeared in Topic’s vinyl days and then was lost like a Northumbrian sunset into darkness. Choosing one segment of the suite is, however, frankly a bit pointless (but that has not stopped me). Steel Skies is modern composition in a traditional vein played on English concertina, Northumbrian smallpipes (Anderson himself), Tony Corcoran (fiddle), Martin Dunn (flute, whistle, piccolo), Robin Dunn (mandolin) and Chuck Fleming (fiddle, viola, mandolin).

This isn’t English music: it’s Northumbrian music. If England were Hungary and Alistair Anderson were Hungarian, he would be weighed down with awards, trophies and solid gold replicas of Northumbrian smallpipes. (This, alas, is England.) Anderson’s achievements might be compared to the Hungarian musician-composer Ferenc Kiss when it comes to composing using traditional idioms, rallying top-notch accompanists and supporting new and established talent.

Steel Skies is the lost ram of English folk music found and returned to the fold to procreate. And Anderson’s Air For Maurice Ogg is pretty damn sweet, too. From the peerless, the peerless Steel Skies (Topic TSCD427, 1982, reissued 2009)

Sanya nikas gaye – Kaushiki Chakrabarty

This bhajan – Hindu hymn – set in the all-purpose Northern Indian raga Bhairavi is stated to be a bhajan “of the late Shobha Gurtu” implying it is one of her compositions. Actually it is a composition by the mystic saint-composer Kabir’s daughter Kamali, although some claim her not to be his daughter but his disciple – since holy men are not supposed to procreate. Maybe therefore Kamali was speaking figuratively in these lyrics when she wrote “Kahata Kamali, Kabeer ki beti” (“Sayeth or Says Kamali, Kabir’s daughter”). But I rather doubt it somehow.

Kaushiki Chakrabarty’s rendition has energy, dynamics, and lashes of feeling as well as displaying her trademark talent for generating panegyrics. It confirms her status as one of the finest vocalists of her generation (she was born in 1980) operating in Hindustani music. From Live at Saptak Festival (Sense World Music 112, 2009)

Ken Hunt’s obituary of Shobha Gurtu from The Independent of Monday, 3 January 2005: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/shobha-gurtu-487736. html

Running On Empty – Jackson Browne

Jackson Browne’s Running On Empty is the sort of song to plant smiles at a humanist funeral. Well, if the ones I go to count. If it ever had to come down to nailing colours to the mast and naming one guitarist whose music would be impossible to live without, it would be a hard call. Too many have shaped my consciousness. Even without stooping to navel-gazing list-making, names like Oscar Alemán, Duane Allman, Vishwa Mohan Bhatt, Martin Carthy, Davey Graham, Jerry Garcia, Nic Jones, Wizz Jones, Brijbushan Kabra, Django Reinhardt, Marc Ribot, Martin Simpson, Richard Thompson and Bob Weir pour off the top of my head. (And this is a deadline, right? Fewer names, less pack drill.) But if I had to take one to the desert island, as opposed to the realm of Giant Donut Discs, Jackson Browne’s principal soloist accompanist – here on lap-steel and fiddle – would be booner than bona as brain fodder and for sheer spectacle and excitement. His name is David Lindley.

Jackson Browne’s Running On Empty is the sort of song to plant smiles at a humanist funeral. Well, if the ones I go to count. If it ever had to come down to nailing colours to the mast and naming one guitarist whose music would be impossible to live without, it would be a hard call. Too many have shaped my consciousness. Even without stooping to navel-gazing list-making, names like Oscar Alemán, Duane Allman, Vishwa Mohan Bhatt, Martin Carthy, Davey Graham, Jerry Garcia, Nic Jones, Wizz Jones, Brijbushan Kabra, Django Reinhardt, Marc Ribot, Martin Simpson, Richard Thompson and Bob Weir pour off the top of my head. (And this is a deadline, right? Fewer names, less pack drill.) But if I had to take one to the desert island, as opposed to the realm of Giant Donut Discs, Jackson Browne’s principal soloist accompanist – here on lap-steel and fiddle – would be booner than bona as brain fodder and for sheer spectacle and excitement. His name is David Lindley.

And what Lindley does here on Running On Empty is a bite-sized taste of why he is so revered. His liquid playing drips with passion and restraint in one of the best bands Jackson Browne ever assembled for touring. Browne’s depiction of life as a touring musician on the album that this comes from comes across as a good US novella about the highs and lows of the road, full of wit melting into wisdom, and, with Rosie, schoolyard humour and (probably) sly reverse psychology of the save him from himself kind. Others might have plumped for the undeniable glory that is Stay with Rosemary Butler and Lindley’s high-flying and falsetto vocals. Don’t cry. Maybe another month? For who knows what will be washed ashore in the future on Giant Donut Atoll? From Running On Empty (Elektra/Rhino 8122-78281-2, 2005)