Lives remembered in 2024

30. 12. 2024 | Rubriky: Articles,Lives

“Such a long, long time to be gone

And a short time to be there.” – ‘Box of Rain’, Phil Lesh (1940-2024)

[by Ken Hunt, London] For many years I was a newspaper obituarist writing for The Guardian, The Independent, The Scotsman, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Times. In addition, I wrote obituaries for many folk magazines. A sample would be Folker in Germany, the EFDSS Journal in the UK, Penguin Eggs in Canada and Sing Out! in the USA.

[by Ken Hunt, London] For many years I was a newspaper obituarist writing for The Guardian, The Independent, The Scotsman, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Times. In addition, I wrote obituaries for many folk magazines. A sample would be Folker in Germany, the EFDSS Journal in the UK, Penguin Eggs in Canada and Sing Out! in the USA.

Since Oxford University Press took over what from 2004 became the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, I have written music-related biographical essays, mainly folk-related, for that massive reference work. I have added more folk-related entries than any individual contributor in the work’s history, including contributors from 1885 to OUP taking over the reins. (It’s laborious but searching the site is easily do-able.) 2024 saw the publication of my entry for the rock musician Spencer Davis: ‘Davies, Spencer David Nelson (known as Spencer Davis) (1939-2020), singer, guitarist, and actor’.

I sometimes miss writing obituaries. Sometimes not. I miss writing them especially when I read ‘list obits’ which don’t capture what made their subject tick and their character. So here are some lives remembered, sometimes with memories, of a number of people who coloured my life.

The musician, activist and co-founder of Paredon Records, Barbara Dane (b.1927) was a huge influence. I was asked to write something about her in October 2024 for my friend Garth Cartwright’s substack. This is a slightly longer version:

“Over decades of interviewing people, many blur into a haze. That never applied to Bernice Johnson Reagon of the all-black female unaccompanied ensemble Sweet Honey in the Rock. It was the only time I can remember the (white) press officer being so intimidated by an act they were publicising they did a runner. They were formidable. Bernice was a complete joy and inspiration to interview. She had seen and done so much. She had been a founding member of the Freedom Singers which the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had birthed. She had been in the midst of the civil rights struggle during very – neutral word – fraught times.

“In the second half of the Eighties, research started with paper sources. One way or the other. With a season ticket to Collet’s Record Shop on New Oxford Street in London since my teens, it was inevitable that I went there when researching the interview.

“That was how I discovered Paredon Records. They were probably the most politicised record company of the period in the United States. Barbara Dane and her future husband Irwin ‘Izzy’ Silber co-founded the label. They put out Bernice’s Give Your Hands to Struggle. And that was how Barbara Dane, at one remove, came into my life.

“Over the next decades Barbara surfaced again and again. I remember reading a telling review by Young in the book I reviewed. The book’s title is The Conscience of the Folk Revival. It is a collection of Israel Young’s writings. The fourth piece is a review of the 1959 Newport Folk Festival. He wrote: “Barbara Dane then came on with blues and folk tunes. She made a hit by composing a blues, on the spot, about coming to Newport.” Enough said.

“It was decades before Barbara and I spoke. Exactly why and when we wound up talking is hazy now. Damn, she was feisty. She was a hoot and very, very amusing. I remember her talking about her admiration for the English political songwriter Robb Johnson. She positively glowed down the phone when I said we were old friends and drinking companions. To have this woman who was so important for the political song movement singing hosannas about Robb Johnson and Leon Rosselson felt like a fillip. She was indefatigable and inspirational. And at an age when, as they say, ‘she should’ve known better’ she was flamin’ incorrigible.”

The 45s of the Paris-born chanteuse Françoise Hardy (b. 1944) were transfixing. It would be a lie to say she did more for my French than hours of schoolroom lessons and vocabulary tests and conjugating verbs. Her lessons in French popular culture helped to motivate my confidence, though. Beginning with a halting attempt to converse in a Parisian shop, by the end of the Sixties I was chatting to drivers when I hitchhiked through France and Belgium. It was part of the deal to keep them awake. À bientôt, Françoise!

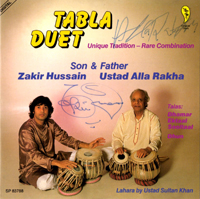

The Hindustani tabla and percussion maestro Ustad Zakir Hussain Qureshi (b. 1951), born a month before me, had been a presence in my musical life for more than ten years before we met in 1981. A child prodigy, he was taught by his father, Ustad Alla Rakha. Hussain’s parents were of Dogra stock. (They would go into Dogri in front of the children when they wanted to discuss something privately.) His dad belonged to the Punjab gharana (school and style of playing) under the tabla virtuoso Ustad Mian Qadir Baksh of Lahore. His father grounded him in its disciplines.

Zakir began performing in public from a young age: “I did my first show when I was seven, so I must have started at least three years before that. I played off and on from about seven to twelve. Then, when I was about twelve or thirteen, I started my professional career.” He went on to work extensively with many of the greatest exponents of the subcontinent’s two classical music systems.

Zakir began performing in public from a young age: “I did my first show when I was seven, so I must have started at least three years before that. I played off and on from about seven to twelve. Then, when I was about twelve or thirteen, I started my professional career.” He went on to work extensively with many of the greatest exponents of the subcontinent’s two classical music systems.

He went on to perform in a range of non-classical fields, notably with the British guitarist John McLaughlin in Shakti and Remember Shakti and Mickey Hart in a variety of ensembles. He was nominated several times for Grammy Awards. He won five. The first two were for Planet Drum and Global Drum Project with Hart. Three were awarded in the final year of his life, including one for This Moment with Shakti.

The first time Zakir and I spoke was as we walked out into the daylight after an all-nighter. He had performed with his dad and the sarangi maestro Ustad Sultan Khan. He said something like “I hear you’ve interviewed my father and Mickey.” And the conversation kept on.

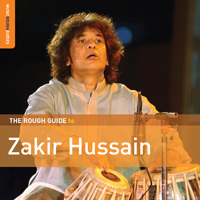

It was an honour to have known Zakir since we were both 30. He brought “new dimensions of eloquence and muscularity to talking in rhythm” (to quote myself from the Rough Guide to Zakir Hussain CD which I compiled and interviewed him for). No chamchagiri, he was one of the most beautiful people, inside and out, I ever met.

The sarodist Aashish Khan (b. 1939), the son of Ustad Ali Akbar Khan and grandson of Ustad Allauddin Khan was one of the young lions who entered the wider discographical imagination with Young Master of the Sarod, released on the World Pacific label or licensed to Liberty. He had the validation of Alla Rakha on tabla. Thanks to his father and his uncle Ravi Shankar, Khan came within George Harrison’s orbit. He appears on Wonderwall Music (1968) and an LP Jugalbandi (1973) on Elektra co-credited to John Barham and Aashish Khan (inevitably) with tabla accompaniment by Zakir Hussain. From talking to him on two occasions, I felt that he was a strangely mixed up fellow. I did not warm to him.

The death of Phil Lesh (b. 1940), the bassist-composer of the Grateful Dead (1965-1995) hit hard. His wide range of musical interests made him a dream interview subject.

Francis McPeake (b. 1942) was a doyen of the uilleann pipes and part of the Northern Irish McPeake dynasty. He was called Francis III for ease of reference. The influence of the McPeakes of Belfast was far-reaching. Their repertoire and performances touched Dylan and the Beatles, Van Morrison and the Byrds.

Ram Narayan (b. 1927) (other spellings of his surname are available) was the first sarangi maestro to elevate the instrument to the concert dais. I regret that I never saw him perform live. That was because he played an enormous part in my Hindustani education. He lit the blue touch-paper to a lifelong love of sarangi in its Hindustani classical, folk, Bombay film industry and qawwali manifestations.

Paredon Records was, as I wrote in the context of Barbara Dane, an important stepping stone in the exploration of the roots of Sweet Honey in the Rock. Their co-founder, the vocalist Bernice Johnson Reagon (b. 1942) was a Civil Rights activist and scholar. Re-reading our Swing 51 also cast me back to Sweet Honey’s ground-breaking role in placing Deaf politics and activism in their music. The feminist and lesbian music scene championed signing in their concerts.

Happy Traum (b.1938), another Swing 51 (Dark Star and Californian folk magazine Folk Scene) interviewee, was a folk musician whose music affected me deeply. The concerts that the Woodstock Mountains Review, of which he was a member, did in Britain in 1981 were real events. He and his wife, Jane also introduced me to Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky. They came to their hotel, fresh and excited from making a pilgrimage to a site of Blakean interest somewhere in, I seem to recall, Dorset. Ginsberg signed the Happy and Artie Traum LP I had with me which he had written the liner dedication for. Kismet. (Ginsberg and I did a number of interviews in subsequent years. One appeared in Mojo with Ginsberg’s early praise for Beck’s ‘Loser’ filleted out. A signed photo of Ginsberg dated “6/18/90” looks down on me on the office wall.) Happy and I kept in touch. He assisted me when I wrote the obituary of his brother Artie Traum for the Guardian in July 2008.

Happy and I resumed our public conversation in interview form in 2018 when I brought him and his old friend from the Greenwich Village days, Bonnie Dobson together for a chinwag for an end-of-life article for fRoots. Afterwards we went for a meal and it was a completely joyous occasion. At his Cecil Sharp House Q&A, asked about him ever distilling this life in print. Perhaps in an ‘Autobiography’ like Dylan’s Chronicles. He replied along the lines of the previous day. “A lot of people – including Jane – have been after me to do it. A couple of people have wanted to do it with me, to be my co-author, that kind of thing. I do have memories but I don’t know if I have enough to really fill out a book and I don’t know if my story is enough to interest people.” It would have and let’s hope he did get something down.

The bluegrass mandolinist Frank Wakefield (b.1934) was one of my wilder interviews. This was thanks to his idiosyncratic style of speech which translated badly to the printed page.

I didn’t learn of the death of Fun-Da-Mental’s Dave Watts in October on Tenerife, Spain until December. Dubbed rather imprecisely the “Asian Public Enemy”, they were ferocious. Aki Nawaz aka Propa-Gandhi had co-founded Fun-Da-Mental in 1991. In solidarity Dave Watts took the stage name Impi-D when he joined. Together they were at the group’s core.

I programmed Fun-Da-Mental as part of the 1997 Rudolstadt Festival in Germany. Back then it was Tanz&FolkFest Rudolstadt, a dance and folk festival. One of the 1997 festival’s Schwerpunkte (focuses) was the year’s regional one commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of India’s self-rule with music and wider arts. 1947 also marked Pakistani Independence from Britain. Enter Fun—Da-Mental.

The raw power of their performance was something else. Watching the reaction to them only felt like a vindication much later once the mushroom cloud had blown away. It polarised. The figurativejout ‘old folks’ were bewildered or shocked. The younger audience was ecstatic and got them. In 2015 the festival produced a limited edition 25th anniversary triple LP set. Fund-Da-Mental’s ‘Ja Sha Taan’ closed Side E. The track had been picked to represent 1997. According to the liner notes, for some, they were Żzu laut, zu roh, einfach unpassend für ein braves Folkfest® (‘too loud, too raw, simply unsuitable for a decent folk festival’). Non, je ne regrette rien. Fun-Da-Mental and its hip hop and sampling bump-started the festival into future worlds. At one point on the way to interviewing Dave I bumped into a friend by the name of Michael Ince in Notting Hill. They were both of British-Bajan (Barbados) stock. Seemed natural to ask Michael if he fancied tagging along. Such a great chinwag. Do get in touch, Michael, if you read this.

Two close friends died in 2024. Chris and Paul were a gay couple. While I was working in Leeds in 1993, I lived with them in Wheldrake, a village 11 km south-east of York. Chris England died in April and Paul Durose in December.

“The dead don’t die. They look on and help.” – D. H. Lawrence, The Letters of D. H. Lawrence: Volume 3, October 1916-June 1921 (1984)