John B. Spencer (1944-2002)

17. 10. 2007 | Rubriky: Articles,Lives

Spencer was blessed with one of the most unmistakeable voices in British popular music. That applied as much to his untrained, gruff vocals as the acuity, wit and verbal drolleries that marbled and ran through his songs. Of him, the folkie, ‘singer-wongwriter’ ((c) 2007, Phil Sutcliffe), actor and general all-rounder, John Tams observed to me, “I don’t know of any other writer, maybe Richard Thompson to a certain extent, who can compete.” In the Penguin Encyclopedia of Popular Music (1998), Spencer’s songs were described as ones written while God was looking the other way. It was a very good line. If I were less modest, I wouldn’t tell you I wrote it. Or that he used it in his publicity.

After leaving Clement Danes Grammar School in 1962, it looked as if his future was Morocco bound, as the Bob Hope and Bing Crosby song puts it so sweetly. The year before he had stacked shelves at the newsagent chain, W.H. Smith’s Holborn branch. The part-time experience would have been altogether forgettable but for the factlet that, as his eldest son Tom put it, “banging books together to keep the shelves dust-free” with him was a character called Brian Jones, shortly to embark on a bright, firefly career with the Rolling Stones. After the last school bell rang for him, Spencer went into the book trade. He joined Panther and progressed through its ranks, interrupted by a year-long diversion to Penguin.

In February 1966 he married Lou who was the subject of so many of his songs, though he also broke into verse (and worse) about his three boys, Tom, William and Syd. Around 1967 – it was the Sixties and some dates get woozy – Panther purred him back to be head of production. In 1970 he founded the Young Artists agency. Young Artists represented great, young illustrators such as Jim Burns and Gordon Crabb. Spencer maintained his interest in pictorial art and graphic design his whole life long. When the Tate Britain ran its William Blake exhibition from November 2000 to February 2001, he came away marvelling to me about how small the reconstruction of Blake’s work space had been and enthusing about the expansiveness of Blake’s visions in cramped physical surrounds.

Throughout his publishing sojourns, Spencer longed to make music as well. All that artistic stuff satisfied him but in 1980 he sold the agency (the present-day Arena agency) to concentrate on making music and writing fiction. Beginning in 1975 he saw seven of his novels published and a batch of other writings anthologised. What Spencer captured in his novels was the pungency of human frailty and humanity’s ability to overcome. Beginning with The Electronic Lullaby Meat Market (1975), he loved viewing lives through distorted prisms. The futuristic, Philip K Dick-ish A Case for Charley (1984) and Charley Gets The Picture (1985) followed. Quake City (1996), Perhaps She’ll Die (1996), Tooth And Nail (1998) and Stitch (1999) completed the seven published during his lifetime. More remained unpublished at his death, for, as Spencer would have guffawed into a Guinness at the Old Pack Horse at Chiswick Green, Grief remained outstanding. (The superbly named publishing house Do-Not-Press published it in 2003.) Peculiarly for somebody who rubbed shoulders with so many people in the public eye, during one of our monthly or so meetings, he confided that the nearest he ever got to “fan collywobbles” was when he went up to Steve Bell – the Guardian cartoonist – in the Tate Modern restaurant (Spencer held a season ticket for the Tate) – to thank him for his cartoons. Spencer had a strongly developed love of the absurd and Bell tickled that sensibility – and his fancy – enormously.

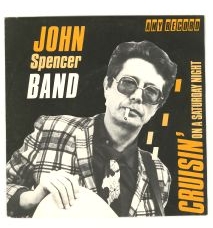

From 1978 onwards, over more than a dozen albums and a handful of singles released on a variety of British and European labels, Spencer threw himself into the recording business. His music never sold anything like the numbers that his old shelf-stacking workmate’s group would, but Spencer made his mark on the British music scene, though Jerry Williams took Cruisin’ (On A Saturday Night) into the Swedish Top 10. As John Collis wrote in 1996, Spencer retained “a faithful constituency of followers” but increasingly that following included name musicians. The scene that nurtured and sustained his songwriting blurred folk, blues, R&B, punk and pub rock. His songs were grounded in the sterling examples of Woody Guthrie, John Lee Hooker, Leadbelly and any number of people who had dealt a good three-chord trick. Interpreters such as Home Service, Augie Meyers, Martin Simpson, Norma Waterson and Jerry Williams took his songs into the wider world. Likewise, the actress Susan Penhaligon, with whom he did poetry and music performances that brought his name to still different audiences. Fast Lane Roogalator – sons Syd and Tom with a little bit of Will Spencer – made an album of twelve of their father’s songs, including Drive-In Movies (about his love-hate relationship with the USA), Only Dancing (power chords reign) and One More Whiskey (one of Spencer’s great parting glasses). Fast Lane Roogalator (2004) was produced by Graeme Taylor, incidentally.

Between 1974 and 1978 he gigged and recorded with his group, the Louts, with Chas Ambler, Johnny G. (Gotting) and Dave Thorne. “It was a pretty anarchic band,” he told me, “but the LP doesn’t reflect that: it’s full of pretty songs. The live gigs were something else. It preceded punk by about four years. In fact just as we were breaking up we were starting to get a few punks arriving at our gigs figuring that as we were called the Louts we were a punk band. We weren’t a punk band: we were an anarchic band. Each gig was either diabolical or fantastic. There was no middle ground.” Spencer later fondly remembered an incident at a Louts’ gig at the Half Moon at Putney as defining the band’s attitude. He had it on tape. “You hear this American voice keep calling out, ‘Haul ass, Spencer! Haul ass!’ Eventually Johnny G. behind the drums shouts back – he didn’t have to shout because he had a mike – ‘We got your money, fuck off!’ To which this American from the back cries out, ‘You didn’t get all my money. I got in for half-price.’ To which Johnny G. shouts back, ‘Then you should have fucked off half an hour ago!’ That summed up the Louts live.” The Half Moon of yore also saw the soon-to-be Elvis Costello open for him. Or maybe it was them – the Louts – because that is what the passage of the years does to people’s memories and I can’t check with Spencer now and Costello isn’t answering my calls.

In 1980, Spencer fell in with members of a collective of musicians based at the National Theatre. Effectively one of the NT’s main house bands, the collective would emerge from the shadow of the Albion Band and its temporary name of the First Eleven – very cricket, very big band – to become the Home Service. (Spencer would team up with three members of its early line-up – the bassist Malcolm Bennett, drummer Michael Gregory and guitarist Graeme Taylor.) The Home Service represented the next major development in folk-rock, the overdue progression away from Fairport Convention, Steeleye Span and the Albion Band. As time and other commitments allowed, a new ‘parallel offshoot’ of the Home Service came into being. It was known as the John Spencer Alternative (or variations on that name theme). Graeme Taylor’s signature Fender Stratocaster lead electric guitar would act as an eloquent foil to Spencer’s Telecaster rhythm guitar for many years.

While the Home Service and The Mysteries went from success to success, Spencer and Johnny G. made the album Out With A Bang (1993). It kept the pressure on. As he explained it, “I had an idea to go back to my early liking for skiffle, Big Bill Broonzy, Leadbelly, down home music, away from the more sophisticated rock format that I’d since developed.” And however secure work in the National Theatre made life for the musicians in the Home Service and the trilogy of plays they appeared in, The Mysteries brought them to the theatrical public, they found themselves missing that particular engagement that brings a band and a hall of concert-goers together. Distanced, one might say. They were a band of power and majesty – no exaggeration – indeed and they missed playing gigs. Spencer had never missed that face-to-face contact but when John Tams did one of his trademark disappearing acts, Spencer was shanghaied as the only fool in town who could do lead vocals with the Home Service. That is, without comparison with Tams or the band’s other, erstwhile vocalist Bill Caddick. Jon Davie, the band’s bassist – who made such a mark in the John Spencer Alternative (or variants thereof) after replacing Malcolm Bennett – recalled with great amusement how Spencer memorised the lyrics from the CD booklet on the way to the Sidmouth festival, periodically slugging from a bottle of scotch. It took three sorts of courage – London, Scotch and Dutch – to walk on stage depping for one of the greatest deliverers of a lyric the British folk scene ever nurtured – John Tams. Spencer had it. He also performed with Martin and Jessica Simpson in Flash Company as a sideman cum featured spotlight hog. In 1990 Spencer formed a semi-acoustic line-up called “Parlour Games” (with double quotes for some reason) that recorded several albums for Round Tower. It was an excellent band and a natural development for Spencer. He spent his musical career balancing the sensibilities of Buddy Holly and Big Bill Broonzy with the power of the Telecaster.

When it comes to acute observations, Spencer was up there with Richard Thompson in terms of quality and output. Neither was prolific but neither ever let up. Several things come across in Spencer’s songs. One is his wonderfully acerbic sense of humour. Crooked-smile observations adorn his songs. In All On The Road Tonight on one of his (inevitably) cassette releases he yelps, “Jesus Christ, they’re all on the road tonight/Perfect strangers out to take my life”. In his song about poverty knocking, Funny Honey, he squints, “Got a gallon of petrol in my tank/Earns interest for the local bank”. At other extremes, he wrote one of the most telling couplets about the Falklands Oil War of 1982: “What do we learn?/We learn aluminium burns”. That song, Acceptable Losses, released on Out With A Bang (1993), ranks as one of the most insightful songs about the South Atlantic debacle written in English, up there with Shipbuilding and Company Policy. Spencer adopted plenty of sides in his songs. Whiteboy on his undated Break & Entry CD (1989) is still one of the better observations on the Irish situation. Spider On A Log on “Parlour Games” (but the old cassette was better) is a song of leave-taking brought on by a fear of flying and a streak of pigheadedness while his body of relationship songs such as Crazy For My Lady, Gingham, White And Blue and Alone Together is nothing short of haunting. Even his backward glance at The London I Knew when neighbours were family and people gave up their seat on the tube looked at how people conduct themselves with friends or strangers. Even some of his apparently most straightforward songs had unwritten subtitles. One More Whiskey, a song that the Home Service made their own (it appears on their live album Wild Life (1992)), is a road song, a much over-subscribed to source of ‘inspiration’ for album filler, not a drinking song. As road song twists go, it rivals Robb Johnson’s Supporting Chumbawamba (At Whitehaven Civic Hall) as an alternative insight into life as a touring musician. To this day, it tends to be the old cassettes that he sold at gigs that I play.

JBS died of endocarditis aged 57 at Charing Cross Hospital, not so far from the flyover they built over his birthplace, on 25 March 2002. In a friendship that straddled three decades, John and I never exchanged a single cross word. To be honest, the worst thing I can think about John was his horticultural hypocrisy. It was a shared joke. When penning one of my favourite lines in one of my favourite songs of his, Forgotten The Blues, he sings – or Martin Simpson – the line “sweet as fresh-cut coriander”. Spencer was an unashamed parsley man when it came to growing the green herb; it was a gauntlet to a coriander grower like me. Actually, it was more banter and shared joke than anything else. Life is fed, watered and made hospitable by boon companions. John Spencer was one. I miss him tremendously.

Written in John’s local, The Old Pack Horse, Chiswick, August 2002, updated in the same borough, October 2007

2 Comments

1. Terry Oakes – Brief&hellip | 5. 12. 2016 | 9:01 am

[…] kind art editor at Sphere Books got him in touch with the late John Spencer, who had just founded an artists’ agency called ‘Young […]

2. admin | 18. 1. 2017 | 7:11 pm

Terry, Thank you so much for your words about John Spencer. He led a remarkable life. I still drink toasts to him, nowadays in wine rather than beer. Ken Hunt