Bess Lomax Hawes (1921-2009)

13. 9. 2010 | Rubriky: Articles,Lives

[by Ken Hunt, London] People’s appreciation of American folk music did not commence with the folk scare of the 1960s and the likes of the Kingston Trio, Peter, Paul and Mary, Joan Baez, Odetta, Buffy Sainte-Marie and Bob Dylan. A generation before them another folk revival, that similarly had no truck with segregation along racial lines, had been under way. Its crop of performers included progressives such as Josh White, Woody Guthrie, Huddie ‘Leadbelly’ Ledbetter and Pete Seeger. Like the next generation, the earlier one wrote new songs in various folk idioms, frequently darts with left-leaning barbs, dosed with class consciousness and social awareness.

[by Ken Hunt, London] People’s appreciation of American folk music did not commence with the folk scare of the 1960s and the likes of the Kingston Trio, Peter, Paul and Mary, Joan Baez, Odetta, Buffy Sainte-Marie and Bob Dylan. A generation before them another folk revival, that similarly had no truck with segregation along racial lines, had been under way. Its crop of performers included progressives such as Josh White, Woody Guthrie, Huddie ‘Leadbelly’ Ledbetter and Pete Seeger. Like the next generation, the earlier one wrote new songs in various folk idioms, frequently darts with left-leaning barbs, dosed with class consciousness and social awareness.

The musician, songwriter and folklorist Bess Lomax Hawes, who died in Portland, Oregon on 28 November 2009, was one of those musicians and songwriters whose worldview coloured, most notably, the Almanac Singers – the template and forerunner for the United States’ first commercially successful and internationally influential folk supergroup, The Weavers. And she may have helped colour yours.

Bess Hawes, born in Austin, Texas on 21 January 1921 came from a Texican family that boasted two of the most important figureheads in the new folk movement. Only the Seegers, as it were, aced them. Her father was the folklorist and musicologist John A. Lomax (1867-1948) and her name derived from her mother, Lomax’s first wife, Bess Baumann, née Brown (1881-1931). Bess Hawes’ brother Alan (1915-2002), six years and some days her senior, became one of the foremost ethnomusicologists of the post-Second World War years in his own right. Her fate was sealed. “Folkloring,” she wrote, “in those days was a family affair.”

Her exclusive Hockaday School education, under financial pressure, made or gave way to a “slum school” with a high Mexican-American intake. Nolan Porterfield, her father’s biographer, quotes her saying, “I was well ahead of them in school terms, but they were ahead of me in life terms. It had a very profound affect [sic] on me – it developed my social attitudes for the rest of my life.” After finishing her education at Bryn Mawr College in 1941 – excessive absenteeism had placed her on probation – she cut out for the wilds of New York City.

There she found herself in the company of a bunch of like-minded people that coalesced as the Almanac Singers. Scratching for a living with odd gigs in small venues, before union congregations, some radio work and some recording, they were yet to become legendary. She was the only one with a regular income, a salary. Their living arrangements bore out their financial fragility. Renting a communal townhouse on Greenwich Village’s Sixth Avenue, Woody Guthrie lived there. Space was so cramped that she and Pete Seeger shared the same attic room. Decorously, in order to divide and maintain the platonic nature of their quarters, a curtain separated them.

She never let on, to use the vernacular, that she had the hots for Seeger. Yet their chaste relationship could never stand up to her father’s inspection. Getting wind of an impending ‘inspection’ she barely had time to move her belongings before he was fuming at the door and Seeger redirected him. In any case, soon afterwards – in 1942 – she married one of the musicians within the Almanacs’ circle, the photographer and musician Butch Hawes, with whom she had two daughters and one son.

Most of her songs served next to no time. Their time came and went in a trice in the manner of the times. Often she – and the Almanacs – simply took a familiar or public-domain melody and wrote new words to it for a strike, a demonstration or a session. One, however, definitely endured. She and Jacqueline Steiner wrote a campaign song for Walter A. O’Brian, Boston’s Progressive Party candidate for mayor in 1949 about a stranded commuter on the Massachusetts Transit Authority who can’t get off the train because he doesn’t have the excess fare. It became a transferrable commuter hymn that could equally apply to Boris Johnson and Transport For London’s price hikes.

“Well, let me tell you of the story of a man named Charlie.

On a tragic and fateful day,

He put ten cents in his pocket, kissed his wife and family

Went to ride on the M.T.A..

Well, did he ever return? – no, he never returned

And his fate is still unlearned.

He may ride forever ‘neath the streets of Boston.

He’s the man who never returned.

Charlie handed in his dime at the Kendall Square station

And he changed for Jamaica Plain.

When he got there, the conductor told him one more nickel.

Charlie couldn’t get off of that train.”

Titled M.T.A. or Charlie On The M.T.A., a decade later the Kingston Trio defanged it and turned it into a major hit. In recognition in 2004, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority branded the CharlieCard, its equivalent of London’s Oyster Card, after the song’s hero. Call it simplistic thinking but the Oyster Card for its part was probably named for generating pearls for big business, as in rooking Charlies, rather than keeping prices down for commuters. If that’s the way your pleasure tends, M.T.A. and the CharlieCard constitute a small but telling win for the voice of the people and, perhaps, folk music.

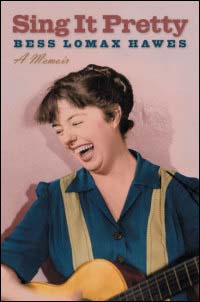

Appropriately, it was the University of Illinois – the same company that had published the biography of her father, Nolan Porterfield’s Last Cavalier – The Life and Times of John A. Lomax (1996) – that published her autobiography, Sing It Pretty: A Memoir (2008). Especially in her later years she bore a hair-raising resemblance to her brother Alan. She was, so to speak, the distaff side of the coin. Doyen of the Smithsonian Institution’s Festival of American Folklife, she became a key figure in the US National Endowment for the Arts before retiring in 1992. In 1993 Bill Clinton felicitated her with the National Medal of the Arts.

Further reading: Sing It Pretty, University of Illinois Press, ISBN: 978-0-252-07509-4 (paperback)