Joe Strummer 1952-2003

2. 7. 2012 | Rubriky: Articles,Lives

[by Ken Hunt, London] Aged 50, Joe Strummer died of a suspected heart attack at home in Broomfield in Somerset on 22 December 2003. In the warm glow and cold slab reality of his death, he seemed to have changed people’s perceptions of ‘reality’ more than most ever do. He was never the Bob Dylan figure that some claimed him to be after his death, though. Mind you, he did get to guest on Dylan’s Down In The Groove (1988).

[by Ken Hunt, London] Aged 50, Joe Strummer died of a suspected heart attack at home in Broomfield in Somerset on 22 December 2003. In the warm glow and cold slab reality of his death, he seemed to have changed people’s perceptions of ‘reality’ more than most ever do. He was never the Bob Dylan figure that some claimed him to be after his death, though. Mind you, he did get to guest on Dylan’s Down In The Groove (1988).

The son of Ronald Mellor, a British civil servant in the Foreign Office who went where the diplomacy of the day posted him, he was born John Graham Mellor in Ankara, Turkey on 21 August 1952. Strummer, as he later ‘became’, had a wider understanding of other cultures than most Brits of his, or indeed previous, generations. He expressed it gloriously, dressing it in a nicely multicultural guise, in the fractured syntax and humorously dubious orthography of the Bhindi Bhagee song on Global A Go-Go (2001). (Ordinarily it would be bindi (ladies’ fingers or okra) and bhaji (fritter).) In this truly amusing ‘list song’, a Kiwi seeking the authentic taste of “mushy peas” asks him where he can locate the grey-green mush that has passed for pea heaven for generations of Britons. The New Zealander gets a stream of gastronomic consciousness for his trouble. From akee (Caribbean dried fish), lassi (Indian yogurt drink), Somali wacky baccy (quite likely an illegal substance) and onwards, Strummer arcs across to music and the sort of nutrients in his musical plate. He and the Mescaleros proclaim their tastes as ragga, bhangra, “two-step tanga”, mini-cab radio and a few etceteras. By now, with years of worthy, well-intentioned cod-reggae pieces/reggae codpieces – Big Youth’s Screaming Target or Toots Hibbert’s Pressure Drop anyone? – and Rock Against Racism gig sensibility behind him, Strummer had become something of a mouthpiece for a multicultural Britain. He was far from the only one, thank goodness. For a taste of that, try and imagine Billy Bragg and The Blokes’ English, Half English (2002) without him. And then the others.

The son of Ronald Mellor, a British civil servant in the Foreign Office who went where the diplomacy of the day posted him, he was born John Graham Mellor in Ankara, Turkey on 21 August 1952. Strummer, as he later ‘became’, had a wider understanding of other cultures than most Brits of his, or indeed previous, generations. He expressed it gloriously, dressing it in a nicely multicultural guise, in the fractured syntax and humorously dubious orthography of the Bhindi Bhagee song on Global A Go-Go (2001). (Ordinarily it would be bindi (ladies’ fingers or okra) and bhaji (fritter).) In this truly amusing ‘list song’, a Kiwi seeking the authentic taste of “mushy peas” asks him where he can locate the grey-green mush that has passed for pea heaven for generations of Britons. The New Zealander gets a stream of gastronomic consciousness for his trouble. From akee (Caribbean dried fish), lassi (Indian yogurt drink), Somali wacky baccy (quite likely an illegal substance) and onwards, Strummer arcs across to music and the sort of nutrients in his musical plate. He and the Mescaleros proclaim their tastes as ragga, bhangra, “two-step tanga”, mini-cab radio and a few etceteras. By now, with years of worthy, well-intentioned cod-reggae pieces/reggae codpieces – Big Youth’s Screaming Target or Toots Hibbert’s Pressure Drop anyone? – and Rock Against Racism gig sensibility behind him, Strummer had become something of a mouthpiece for a multicultural Britain. He was far from the only one, thank goodness. For a taste of that, try and imagine Billy Bragg and The Blokes’ English, Half English (2002) without him. And then the others.

Mellor said he adopted his Strummer moniker because he felt, with a nicely self-deprecating touch, the word fitted his guitar-playing prowess. Supposedly an earlier interlude had him masquerading as Woody Mellor in homage to Woody Guthrie. True or not, it fitted because Guthrie knew how to thrash a guitar better than most when it was needed. And when the time came around he pawned his guitar with the ‘This Machine Kills Fascists’ slogan…

Art flirtations behind him, Strummer played with the 101ers, a damn average pub rock group. Early pre-Clash recordings by Joe Strummer and the 101ers appeared as the album Elgin Avenue Breakdown (Revisited) (2005). The title alluded to the number of the house in which they squatted. Back in the day, that district of West London was one of London’s many squatting hotbeds offering rebellion as soon as the social security giro came. During Strummer’s tenure, the group released one single. Elgin Avenue Breakdown… comprised an unreleased studio session with live recordings with the approval of Strummer’s widow, Lucinda. The 101ers had been a fairly standard pub rock doing R&B covers until the Sex Pistols supported them at the Nashville Rooms in West London but the experience shaped Strummer’s approach and led in time to The Clash.

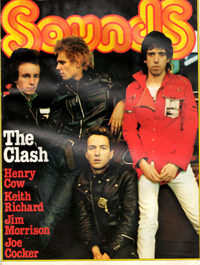

The Clash happened when two members of the London SS – the group’s guitarist Mick Jones and bassist Paul Simonon – whisked Strummer away. They needed a new name and the name they chose was The Clash.

Punk was a movement full of kidding on about rage and nihilism while wallowing in hedonistic complacency. (The rebellion begins when the social security cheque arrives, this pub closes and the like.) When it came to the disdainful matter of politics or any semblance of political insight, there was only one real exception to the punkish rule and The Clash was it. They rescued the punk movement from its fashion statement manifesto and manipulation in ways that Malcolm McLaren and the Sex Pistols could only dream of, fantasise over, or have nightmares about. When it came to going through the butter of society, the Sex Pistols, the Buzzcocks and Damned were the hammer and The Clash the hot knife.

Punk was a movement full of kidding on about rage and nihilism while wallowing in hedonistic complacency. (The rebellion begins when the social security cheque arrives, this pub closes and the like.) When it came to the disdainful matter of politics or any semblance of political insight, there was only one real exception to the punkish rule and The Clash was it. They rescued the punk movement from its fashion statement manifesto and manipulation in ways that Malcolm McLaren and the Sex Pistols could only dream of, fantasise over, or have nightmares about. When it came to going through the butter of society, the Sex Pistols, the Buzzcocks and Damned were the hammer and The Clash the hot knife.

The Clash had an authentic voice, not some posturing snide snarl or curled identikit lip for the crowd’s benefit. Punk swiftly degenerated into something else once a waft of dosh maced the young hopefuls. White Man In Hammersmith Palais howled about “turning rebellion into cash” and in Lost In The Supermarket they became the “special offer”. (As ever shall be, once ground smooth by the star-making machinery, wry amen.) Yet surely, if Mick Jones’ power chords count for anything, The Clash showed off a bar sinister genealogy that pointed to the Kinks as much as punk or reggae.

Parenthetically, John Lydon emerged post-punk, post-PIL as truly one of the most articulate, engaging and though-provoking interviewees of them all after his Johnny Rotten phase.

After Strummer’s death, Billy Bragg, one of many launched on the wings of The Clash, called Strummer “the political engine of the band.” (In the spurious link twilit zone, the working title for Combat Rock (1982) was Rat Patrol From Fort Bragg.) Good soundbite. More accurately, William, Strummer was the fuel that drove the movement’s only political engine. And The Clash only got better, got proficient, and got better at rock than at punk. And got good at humour: Julie’s In The Drug Squad still tickles.

Like most bands, The Clash’s five albums between 1977 and 1982 were downright variable in quality. The one that stood out was London Calling (1979). Try the strongly recommended three-CD The Clash On Broadway (1991) for a better career overview. It contains the stuff that elevated them above the ranks. Plus. Between its live Lightning Strikes (Not Once But Twice) with its Loaded Velvet Underground raucousness, its Sandinista! outtake Every Little Bit Hurts and the unedited Straight To Hell (which does what the Kinks’ Lola failed to pull off, thanks to the BBC’s worry-warts, namely, including the unexpurgated alternative to ‘cherry cola’), The Clash On Broadway captures the band’s essence better than pages of words (and I include these). The group disbanded in dragged-out silliness, drugged-out stupidity and low-life recriminations in 1985. It still took years for Strummer to admit his mistake about firing his songwriting partner Jones from the band in 1983. At least Strummer had the graciousness to do the decent thing and make amends.

To say that Strummer went on to do a lot of nothing for several years is only partially true. There was a lot of darkness and much foolishness after The Clash folded its hand. He worked on several film projects of varying quality. He racked up work with films such as Walker, Mystery Train, Lost In Space and Sid And Nancy – either/and/or acting/doing the music. There were other picture palace credits but they don’t matter. He filled in with the Pogues for Shane MacGowan for a while. Bless him and most of all, Strummer had the integrity not to do retreads of Should I Stay Or Should I Go (on the back of that jeans advert hit), This Is Radio Clash or Rock The Casbah for the king’s ransom offered to participate in a Clash reunion tour.

Instead, he put together one of Britain’s great bands of the turn of the Millennium – Bragg and the Blokes rank there too – and they were the Mescaleros. They first emerged in 1999. The songs told great stories, perhaps sung through a distorting prism, but worthy to sit beside the Bill Kirchen-led Moonlighters’ own mescal visions. Rock, Art and the X-ray Style was good. It was wonderful to see song credits going to Pablo Cook, Tymon Dogg, Scott Shields, Martin Slattery and Strummer. It said volumes about the organic creative process that happens in bands. The Mescaleros’ collective credits were just another reason to hope they were making music for a New Age.

Strummer did something else that brings him into the Grateful Dead class. Over the Dead’s thirty-year history, San Francisco’s finest did more benefits and raised and distributed more funds than arguably any music act had in history. Strummer shared a similar spirit. In his last month, he was working with Bono – U2 had been massively influenced by The Clash – and Dave Stewart on a track for a Nelson Mandela-driven project to do with awareness of AIDS in Africa. He also did a firefighters’ union benefit at Acton to the west of the metropolis at which Mick Jones, the man he had had sacked in 1983, joined him on stage.

This Life is an edited and expanded and revised version of an obituary that appeared in the Canadian magazine Penguin Eggs after Strummer’s death. In the meanwhile, we have Chris Salewicz’s Redemption Song (HarperCollins, 2006) to cast further light on Joe Strummer and there is Strummerville

For about Strummerville go to http://www.glastonburyfestivals.co.uk/areas/strummerville/.