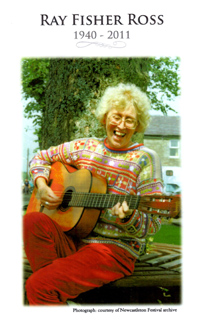

Ray Fisher 1940-2011

19. 9. 2011 | Rubriky: Articles,Lives

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Scottish folksinger Ray Fisher once told me that she had a series of scheduled performances in Czechoslovakia that were abruptly cancelled when the Soviet bloc forces had the bad manners to invade in 1968. The following year, rescheduled concerts finally took place. She recalled the mayor of one town greeting her. Two Soviet officers flanked him. The mood was tense. Then, one of them broke the ice by asking her excitedly whether she knew the Beatles. (With her winsome charm, no doubt she pulled it off effortlessly but alas I have no memory of how exactly she got out of that one.) As part of the cultural exchange, the tour introduced her to dudy – Czech bagpipes and ‘bagpipes’ in Czech – and she remembered the experience with wry fondness.

[by Ken Hunt, London] The Scottish folksinger Ray Fisher once told me that she had a series of scheduled performances in Czechoslovakia that were abruptly cancelled when the Soviet bloc forces had the bad manners to invade in 1968. The following year, rescheduled concerts finally took place. She recalled the mayor of one town greeting her. Two Soviet officers flanked him. The mood was tense. Then, one of them broke the ice by asking her excitedly whether she knew the Beatles. (With her winsome charm, no doubt she pulled it off effortlessly but alas I have no memory of how exactly she got out of that one.) As part of the cultural exchange, the tour introduced her to dudy – Czech bagpipes and ‘bagpipes’ in Czech – and she remembered the experience with wry fondness.

Born in Glasgow, Scotland on 26 November 1940, in 1962, she had married Colin Ross, the fiddler and piper, and later co-founder of the High Level Ranters, and settled in Tyneside. With her marriage to Colin, she was wed – or, as she sometimes joked – widowed to the pipes. She was one of six daughters – Jean, Joyce, Cindy, Audrey and Priscilla – and one token son – Archie – born into a family with catholic musical tastes that included light operatic and parlour fare (their father John Galbraith Fisher sang in the City of Glasgow police choir), Scots and, since their mother, Marion née MacDonald (known as Morag or Ma Fisher) had it as her mother tongue, Gaelic songs. Like many folkies of her generation, Britain’s skiffle movement was the springboard to a greater awareness of folk music. Through a fluke of fate and proximity, a bloke who owned a local record shop lent US import LPs on Folkways by Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, Buell Kazee and Aunt Samantha Bumgarner to Hamish Imlach, whose Cod Liver Oil and The Orange Juice – Reminiscences of a Fat Folk Singer – discusses the early Glasgow folk scene. Imlach borrowed them because he was the one with a record player that could play them.

Born in Glasgow, Scotland on 26 November 1940, in 1962, she had married Colin Ross, the fiddler and piper, and later co-founder of the High Level Ranters, and settled in Tyneside. With her marriage to Colin, she was wed – or, as she sometimes joked – widowed to the pipes. She was one of six daughters – Jean, Joyce, Cindy, Audrey and Priscilla – and one token son – Archie – born into a family with catholic musical tastes that included light operatic and parlour fare (their father John Galbraith Fisher sang in the City of Glasgow police choir), Scots and, since their mother, Marion née MacDonald (known as Morag or Ma Fisher) had it as her mother tongue, Gaelic songs. Like many folkies of her generation, Britain’s skiffle movement was the springboard to a greater awareness of folk music. Through a fluke of fate and proximity, a bloke who owned a local record shop lent US import LPs on Folkways by Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, Buell Kazee and Aunt Samantha Bumgarner to Hamish Imlach, whose Cod Liver Oil and The Orange Juice – Reminiscences of a Fat Folk Singer – discusses the early Glasgow folk scene. Imlach borrowed them because he was the one with a record player that could play them.

Recorded music, like these Folkways LPs and the Weavers, fed the heads of Archie, Bobby Campbell and Ray informing their skiffle group’s repertoire. “It was really through Archie,” she told Howard Glasser in an interview for Sing Out! in 1974 (Volume 22/number 6), “that I first started singing. Archie and I and Bobby Campbell went to the same school. Bobby played violin in the school orchestra. At the time in Glasgow there were lots of skiffle groups, and Archie and Bobby decided they were going to start a group.” The Wayfarers would open for Pete Seeger in Glasgow, Edinburgh and Aberdeen. And that was no small deal.

Ray also studied with the Scottish Traveller ballad singer, Jeannie Robertson, spending her school summer holidays in her finals year and learning from her . It was an extraordinarily brave thing to do. It flew in the face of convention since many viewed Travellers with suspicion. By staying at Robertson’s home in Aberdeen, she dismissed prejudices and warinesses about the Traveller community. Over those six weeks, she imbibed open-mindedly. When she left, she understood. It was one of the experiences that turned her into one of Scotland’s finest interpreters of folk material. She heard Jeannie Robertson, later, in 1968, to be appointed MBE for her services to traditional music, sing not only the big ballads but also the radio hits of the day whilst doing the washing up. Ray Fisher never unlearned those lessons.

Ray and Archie Fisher formed a duo which lasted until 1962 when she moved to Tyneside. Archie recalled at Ray’s funeral that living in two different cities meant that they had little chance to rehearse for their appearances. Rehearsing was quite important as the duo was appearing on the Scottish television teatime magazine programme, Here And Now. Actually, very important, as they were going out live. Since his financial position was weaker, he would reverse the charges (call collect for North American readers) and they would rehearse for their broadcasts over the phone. Camouflaging the extent of their under-rehearsal on screen they would look directly into each other’s eyes. This look is captured well in one famous image from Brian Shuel’s portfolio of photographs. One important reason for looking so intently at each other is that they were lip-reading as well in order to get the lyrics right. The duo’s EP Far Over The Forth EP (Topic, 1961) captures the period and the folkier side of their repertoire well but in the television studio they were also running through an output of topical songs in the style of the day, many of which were learnt for the transmission and then forgotten. Far Over The Forth Scots had an unabashed Scottish focus and regionality, something that would take on a greater significance in future years. Both Dick Gaughan and Anne Briggs took direction from it.

Singing for Labour Party events, Centre 42 concert parties, pro-CND, anti-Polaris protests and Aldermaston marches brought Ray further into left-wing political circles. In the period between 1963 and 1965, she contributed to three important projects and a handful of ‘various artists’ projects, notably the fake Edinburgh Folk Festival anthologies (actually recorded specifically for Decca in a studio ‘re-creation’ of the festival experience). The first was A.L. Lloyd’s The Iron Muse. This was, Bert Lloyd explained in the LP notes, an album of industrial songs. “‘What is folk song?’ he asked as his opening rhetorical flourish. “The term is vague and seems to be getting vaguer. However, the songs on this record may conveniently be called ‘industrial folk songs’ for without exception they were created by industrial workers out of their own daily experience and were circulated, mainly by word of mouth, to be used by the songmakers’ workmates in mines, mills and foundries.” Both Ray and her husband Colin contributed to this project, as they did to the sixth On The Edge radio ballad, a form of audio-documentary with song, devised and developed by Ewan MacColl, Charles Parker and Peggy Seeger for BBC radio. First broadcast in February 1963, it addressed the transition from childhood to adolescence to adulthood. (First released on LP on the Argo label in 1967, it was reissued as a Topic CD (Topic TSCD 806) in 1999 as part of Topic’s radio ballad release programme.)

Most important of all, many would consider, was Topic’s LP The Fisher Family, recorded in 1965 and released the following year. Its subtitle said ‘Traditional and New Songs from Scotland’. Bill Leader recorded it at the Fisher Family palace, while Joe Boyd, his assistant on the job (later to achieve other things through Witchseason, Island, Elektra, Reprise and more, but also the snapper that captured the cover image), slept in the car outside because there was no more room in the palace. At her funeral, her surviving sisters sang Ewan MacColl’s Come All Ye Fisher Lasses, the album’s opening track on which Ray had sung lead.

Most important of all, many would consider, was Topic’s LP The Fisher Family, recorded in 1965 and released the following year. Its subtitle said ‘Traditional and New Songs from Scotland’. Bill Leader recorded it at the Fisher Family palace, while Joe Boyd, his assistant on the job (later to achieve other things through Witchseason, Island, Elektra, Reprise and more, but also the snapper that captured the cover image), slept in the car outside because there was no more room in the palace. At her funeral, her surviving sisters sang Ewan MacColl’s Come All Ye Fisher Lasses, the album’s opening track on which Ray had sung lead.

A short digression. The tail end of Cyclone Katia was still blowing the day of the funeral – 12 September 2011 – and trains down to London were delayed more than somewhat by fallen trees. When we reached London, a disparate band of stranded travellers arrived to missed connections and last trains gone. The rail company laid on taxis and bundled people with nearby destinations off together. Finding common cause in adversity, we chatted and a Scottish woman talked about missing her friend’s wedding because of rail staff misdirecting on to a train, the first stop turned out to be the wrong side of the border, Newcastle upon Tyne. She spoke of crying uncontrollably and MacColl’s words “greet like a wean” (‘weep like a child’) from Come All Ye Fisher Lasses came back to me. After hearing them an English voice use those words, she repeated them in half-surprise and burst into laughter.

Ray expressed little interest in recording, being averse to the regime of recording studios and much preferring the spontaneity of singing to living, breathing humans or delivering something live, say, to radio. Never partial to the studio recording process, she successfully managed to manoeuvre in the most eel-like of ways and succeeded in putting off recording her debut solo debut, The Bonny Birdie (Trailer, 1972) into the next decade. This was a feat in itself. Again recorded by Bill Leader (with Seumas Ewens assisting), its producer Ashley Hutchings brought in a bunch of musicians to re-upholster the arrangements with Martin Carthy, Tim Hart and Peter Knight and Hutchings himself from the Steeleye Span circle, Alistair Anderson and Colin Ross by then members of the High Level Ranters, Bobby Campbell (long past his Wayfarers days) and Liz and Stefan Sobell. Typical of her dry wit, she explained of The Forfar Sodger (The Forfar Soldier) that, “To hirple means to hobble (as if you didn’t know!)” The album was later reissued by Highway Records and still later fell foul of the contractual conundrums presented by the demise of Bill Leader’s Leader and Trailer labels. Ten years later she made her second album Willie’s Lady (Folk-Legacy, 1982). Less florid, more natural than The Bonny Birdie, it felt closer to her live act – not that records any longer needed to be mere reflections of concert performance or a folk club repertoire. Its magnificent title track, a slow build-up of accumulated repetitions from a pre-televisual age, appeared six years after Martin Carthy’s version on Crown of Horn (Topic, 1976). In fact, they had cracked their individual versions – hers in Scots, his in English – the same night when Carthy stayed with the Rosses in Monkseaton. Another highlight was the closing track, her treatment of Alan Rogerson’s version of When Fortune Turns The Wheel – a song she had learned from Lou Killen. Between those two songs you discover what made her unique as a singer and song interpreter.

In 1991 she released her third and final solo album Traditional Songs of Scotland which complemented Saydisc’s English and Welsh companion volumes – Jo Freya’s Traditional Songs of England and Siwsann George’s Traditional Songs of Wales/Caneuon Traddodiadol Cymru. Its out-take Now Westlin’ Winds, with Martin Carthy accompanying on guitar, from the same sessions appeared on the seasonal round anthology, All Through The Year (Fledg’ling, 1991).

In 1991 she released her third and final solo album Traditional Songs of Scotland which complemented Saydisc’s English and Welsh companion volumes – Jo Freya’s Traditional Songs of England and Siwsann George’s Traditional Songs of Wales/Caneuon Traddodiadol Cymru. Its out-take Now Westlin’ Winds, with Martin Carthy accompanying on guitar, from the same sessions appeared on the seasonal round anthology, All Through The Year (Fledg’ling, 1991).

Long associated with the Newcastle upon Tyne folk scene, whether ‘knitting’ bags for her pipe-maker husband’s much sought-after Northumbrian pipes or just singing or adding drolleries of the spoken monologue or parody song type, she appeared on 50 Years of Folk Music in Newcastle (Ceilidh Connections, 2009) performing her arch monologue Behave Yoursel’ – a treatise on declining standards in public places – and, accompanied by Tom Gilfellon on guitar, Generations of Change and Old Maid In A Garret. It was a no-frills double-CD celebrating a half-century of one of Britain’s finest folk hubs – the club that began as Folksong and Ballad before becoming the Bridge Folk Club and most especially known from its time at the Barras Bridge Hotel in the city. It ranked, I wrote in R2, as “one of the folk scene’s very most important outposts when the likes of Mike Waterson … willingly thumbed it from Hull to Liverpool (pre-motorway system) in order to visit the Spinners’ folk club.” I continued, “You get the club’s founding fathers – Johnny Handle and Louis Killen – in the glad company of past and present High Level Ranters (surely verging on the holotypic in a folk revival band sense and absolutely one of Britain’s finest), Chris Hendry, Ray Fisher, Pete Wood, John Brennan and others. … 50 Years of Folk Music in Newcastle brilliantly distils the essence of not merely one but this country’s whole folk club movement.”

Long associated with the Newcastle upon Tyne folk scene, whether ‘knitting’ bags for her pipe-maker husband’s much sought-after Northumbrian pipes or just singing or adding drolleries of the spoken monologue or parody song type, she appeared on 50 Years of Folk Music in Newcastle (Ceilidh Connections, 2009) performing her arch monologue Behave Yoursel’ – a treatise on declining standards in public places – and, accompanied by Tom Gilfellon on guitar, Generations of Change and Old Maid In A Garret. It was a no-frills double-CD celebrating a half-century of one of Britain’s finest folk hubs – the club that began as Folksong and Ballad before becoming the Bridge Folk Club and most especially known from its time at the Barras Bridge Hotel in the city. It ranked, I wrote in R2, as “one of the folk scene’s very most important outposts when the likes of Mike Waterson … willingly thumbed it from Hull to Liverpool (pre-motorway system) in order to visit the Spinners’ folk club.” I continued, “You get the club’s founding fathers – Johnny Handle and Louis Killen – in the glad company of past and present High Level Ranters (surely verging on the holotypic in a folk revival band sense and absolutely one of Britain’s finest), Chris Hendry, Ray Fisher, Pete Wood, John Brennan and others. … 50 Years of Folk Music in Newcastle brilliantly distils the essence of not merely one but this country’s whole folk club movement.”

Folk clubs were Ray’s driving force when it came to making music. She loved the folk club scene. She stoutly avoided recording under her own name. In an interview with me, published in Swing 51Crab Wars she and a front row of nasty people hid crab shells under their chairs. At the critical moment, the concealed crab carapace percussion was whipped out and clattered in an attempt to get the Kippers to corpse.

PS At Ray’s funeral in Whitley Bay there was much piping and singing. At one point Martyn Wyndham-Reed movingly sang The Rose, a Greenwich Village single of his on which Ray had sung in 1984 – the same song that Bette Midler had sung. Adding the backing vocals were Cilla Fisher, Di Henderson (on whose By Any Other Name (DH, 1991) Ray had also sung) and Cilla’s daughter Jane.

Jane sings with the Glasgow-based electro, punk and rock’n’roll band Fangs. Wonderful to discover that yet another generation of Fishers is singing. For more information and to try This Is Art for starters, visit http://www.myspace.com/fangsfangsfangs

The main image is © Sandy Paton/Folk-Legacy Records, cropped from the album sleeve of Willie’s Lady, the yesty image of Ray from her funeral programme is courtesy of the Newcastleton Festival archive, photographer unknown. The copyright of all other images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers.

With thanks to Cilla Fisher.