Remembering Jerry Garcia (1942-1995)

9. 8. 2016 | Rubriky: Articles

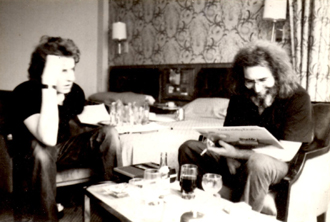

[by Ken Hunt, London] In April 1981 I walked into the anteroom of hotel round the corner from Green Park tube station in Central London to do the first of a series of booked interviews with members of the Grateful Dead. A hirsute gentleman, actually an aureole of hair with a splash of face, eyed me up and crossed the room to talk to me. We shook by way of opening pleasantries (his handshake was like the Dave Allen crack: “Am I the Irish comedian with half a finger? No, I’m the Irish comedian with nine and a half fingers.”). We fell into conversation straightaway.

[by Ken Hunt, London] In April 1981 I walked into the anteroom of hotel round the corner from Green Park tube station in Central London to do the first of a series of booked interviews with members of the Grateful Dead. A hirsute gentleman, actually an aureole of hair with a splash of face, eyed me up and crossed the room to talk to me. We shook by way of opening pleasantries (his handshake was like the Dave Allen crack: “Am I the Irish comedian with half a finger? No, I’m the Irish comedian with nine and a half fingers.”). We fell into conversation straightaway.

His interview had failed to show on time. My interview was still running in the park. All around us a low-frequency mêlée of voices was in full swell. Noise, like indolence, has its time and place, so we elected to go somewhere quieter. And that was how an overdue, towel-wrapped drummer with the Grateful Dead called Mickey Hart first met me. I was already doing an impromptu interview with his band mate Jerry Garcia, whom I was due to interview the next day. And the following day when the interview proper was under way, Bob Weir for reasons I cannot fathom joined us in the same room. He got so intrigued with the conversation that we beckoned him over to join in the conversation.

Garcia was San Francisco-born and very much bred in the Californian bone. He breathed his first breath on 1 August 1942, the second of two sons born to Ruth and José ‘Joe’ Garcia. His father had been a swing clarinettist and bandleader before falling foul of his local cock-of-the-midden musicians’ union. Jerome John Garcia was named after Jerome Kern. It is no exaggeration to say that Garcia became a walking musical encyclopaedia, cross-referenced in the bizarrest of ways. He made connections the whole time. They ranged from the country music and opera he heard in his boyhood home to his brother Tiff’s early love of rock ‘n’ roll and rhythm ‘n’ blues. And beyond. At the age of 15 he got his first guitar, though this involved him pestering his mother to return the accordion that she had substituted for the birthday present he really wanted. The loss of part of a finger in a boyhood accident just helped shape his style, like it did Reinhardt. Style is an expression of limitations.

Garcia was San Francisco-born and very much bred in the Californian bone. He breathed his first breath on 1 August 1942, the second of two sons born to Ruth and José ‘Joe’ Garcia. His father had been a swing clarinettist and bandleader before falling foul of his local cock-of-the-midden musicians’ union. Jerome John Garcia was named after Jerome Kern. It is no exaggeration to say that Garcia became a walking musical encyclopaedia, cross-referenced in the bizarrest of ways. He made connections the whole time. They ranged from the country music and opera he heard in his boyhood home to his brother Tiff’s early love of rock ‘n’ roll and rhythm ‘n’ blues. And beyond. At the age of 15 he got his first guitar, though this involved him pestering his mother to return the accordion that she had substituted for the birthday present he really wanted. The loss of part of a finger in a boyhood accident just helped shape his style, like it did Reinhardt. Style is an expression of limitations.

Ultimately, Jerry Garcia was a rock guitarist for people who outgrew rock guitar. His playing started out full of folk, bluegrass and rock’n’roll, but was always imbued with a tincture of other elements, like avant-garde, Western and non-Western classical music, show tunes, soundtrack material (including, famously, Close Encounters of the Third Kind) and, naturally, jazz. The jazz elements that flowed through his work were various and multilayered. Miles Davis and John Coltrane were givens. Ornette Coleman represented a torch being carried forward and held aloft. But like any acoustic guitar player with diligent research tendencies, Django Reinhardt and his largely forgotten Argentinean counterpart Oscar Alemán were influences. (His take on Alemán’s version of Irving Berlin’s Russian Lullaby, on 1974’s Compliments of Garcia, is priceless, with strong violin from Richard Greene, Amos Garrett on trombone and Joel Tepp on clarinet.) And given San Francisco’s importance on the beat and bohemian barometer the crypto-significant jazz-rap of Lord Buckley and Ken Nordine never flew south. The twin keys to so many of the elements in his musical universe were improvisation and discipline.

On 9 August 1995 Jerry Garcia began the next stage on the wrong side of the grass. When he died aged 53 in Forest Knolls, California, it was more awaited than unexpected. Yet still a shock. The news shockwaves of his death travelled ultra-fast. And despite the time difference, the morning after, UK time, I wrote the day off to sit beside the Thames at Kingston. Outside The Bishop Out Of Residence I nursed a couple of beers and reflected on Garcia’s life and works and particularly the man as I knew him. It was not a time for music.

On 9 August 1995 Jerry Garcia began the next stage on the wrong side of the grass. When he died aged 53 in Forest Knolls, California, it was more awaited than unexpected. Yet still a shock. The news shockwaves of his death travelled ultra-fast. And despite the time difference, the morning after, UK time, I wrote the day off to sit beside the Thames at Kingston. Outside The Bishop Out Of Residence I nursed a couple of beers and reflected on Garcia’s life and works and particularly the man as I knew him. It was not a time for music.

Much like the Indian actress Karuna Banerjee expressed it of Chhabi Biswas, I shall never be able to say, “I had known him well.” Garcia and I met to do interviews three times over two decades. The rest was bumping into him backstage. He was unfailingly courteous, widely read and an indefatigable conversationalist. I declined to interview him later, though offered him as an interviewee. I never regretted that. Norma Waterson, who later covered the Garcia/Hunter song Black Muddy River, asked me what he was like. I told her truthfully that he was one of the best conversationalists on the planet that I had ever met.

The closing words go to or mutual friend, the former Grateful Dead keyboardist Tom Constanten. “What I miss most about Jerry, aside from and in addition to his playing and his musicality, is how he was backstage and at the hotel, his takes on things, the quickness of his wit, the new things he was reading, discovering, into.” That was Garcia all over and it showed in his music.

The image of Ken Hunt and Jerry Garcia is © Roy Wilbrahamt/Swing 51 Archives