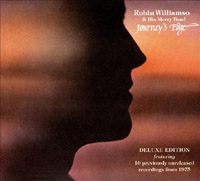

Robin Williamson’s Journey’s Edge

21. 3. 2011 | Rubriky: Articles,CD reviews

[by Ken Hunt, London] Journey’s Edge is a stepping-stone, a betwixt and between work. It captures Robin Williamson poised in midair or mid-dream skipping from the fading psychedelic sepia of The Incredible String Band and yet to land sure-footedly on the other shore. Though nobody knew that on Journey’s Edge‘s unveiling in 1977. That only became apparent with the Merry Band of American Stonehenge later that year and A Glint At The Kindling in 1978. Journey’s Edge was Williamson’s début solo release after the splintering of the ISB in late 1974. The ISB’s final flurry of creativity – many would have substituted ‘death throes’ – as evidenced by No Ruinous Feud (1973) and Hard Rope And Silken Twine (1974) and the half-remarkable, rarely remembered swansong films Rehearsal and No Turning Back (both 1974), had increasingly bled them of their heyday’s constituency. The thrill had gone. To be frank, Journey’s Edge represented something between foreboding and tenterhooks anticipation. Williamson rose to the challenge, as perhaps only he knew how far to go. Journey’s Edge is relocation music par excellence.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Journey’s Edge is a stepping-stone, a betwixt and between work. It captures Robin Williamson poised in midair or mid-dream skipping from the fading psychedelic sepia of The Incredible String Band and yet to land sure-footedly on the other shore. Though nobody knew that on Journey’s Edge‘s unveiling in 1977. That only became apparent with the Merry Band of American Stonehenge later that year and A Glint At The Kindling in 1978. Journey’s Edge was Williamson’s début solo release after the splintering of the ISB in late 1974. The ISB’s final flurry of creativity – many would have substituted ‘death throes’ – as evidenced by No Ruinous Feud (1973) and Hard Rope And Silken Twine (1974) and the half-remarkable, rarely remembered swansong films Rehearsal and No Turning Back (both 1974), had increasingly bled them of their heyday’s constituency. The thrill had gone. To be frank, Journey’s Edge represented something between foreboding and tenterhooks anticipation. Williamson rose to the challenge, as perhaps only he knew how far to go. Journey’s Edge is relocation music par excellence.

Journey’s Edge‘s tales of journeying and arrival recall his responses to moving from Scotland to the United States at the turn of the year, 1974 into 1975, and his lingering looks back to Europe. Plus the album is very much in the stamp of its time and place of origin with its jazz-funk into Bee Gees’ disco – quite unlike the sound of his first West Coast agglomeration or fling, the Far Cry Ceilidh Band. At a musicians’ party he ran into one of the mainstays of the Merry Band, Sylvia Woods – the deliverer of Journey’s Edge‘s opening flourish and statement of intent on Border Tango. She recalled in an interview in Swing 51 that their meeting happened in December 1975. Woods, under the influence of Alan Stivell had begun playing harp and had gone so far to travel to Waltons in Dublin to buy a harp and harp tutors. She crammed them, Stivell and Derek Bell’s harp playing with the Chieftains into her cranium. She also admitted that before meeting him at the party she had heard neither of Robin Williamson nor the Incredible String Band. But she was working at McCabe’s Guitar Shop on Pico Boulevard in Santa Monica, which doubled as one of the Los Angeles area’s famous folk clubs. It became one of the Merry Band’s regular gigs.

In January 1975 she and Williamson started welding something together, sucking two musicians in her circle, the banjoist Kevin Carr and fiddler Bill Jackson, into their orbit. They were soon replaced by, as it were, the band’s two other, core musicians, Christopher Caswell and Jerry McMillan. The benchmark Merry Band, as they became known, gave their début concert on the 4th of July 1976, thus turning a humdrum date into a memorable one, one that should forever be remembered. Regrettably, Williamson cannot remember where it was. That quartet remains a benchmark of excellence and in Williamson’s memory “a happy band”. They would play their final concert at McCabe’s in December 1979. Although they never told their audience it was their final concert, it went out over national public radio and was subsequently released as an album. “We changed a bit through all the albums,” Sylvia told me in 1980, “but we were the Merry Band with a couple of extra people for Journey’s Edge.”

Williamson’s relocation to Los Angeles led to a burst of creative activity of varying kinds. Much of it was, however, hard to obtain outside continental North America in that great pre-internet age when learning about what he was doing meant reading counter-culture music press and discovering small-circulation literary and music magazines – mine, Swing 51 (1979-1989), being but one. Parallel with sketching, developing and head-arranging the material on Journey’s Edge, he wrote two music tutors for the fiddle and penny whistle, had extracted material from his “surreal autobiography” or “lyric montage” Mirrorman’s Sequence published in the 1977 West Coast anthology Outlaw Visions – it also included the work of writer-composer Paul Bowles and the painter-illustrator Neon Park of Frank Zappa, David Bowie and Little Feat cover art repute – and that year’s co-written thriller called The Glory Trap published under the composite pen name Sherman Williamson.

Fictions, collusions and inventions of varying sorts were Williamson’s forte, he would be the first – or, as Mirrorman, last – to agree. The ISB had revelled in their psychedelic prayer, post-Gilbert and Sullivan silliness and ‘premature world music’ guises. Along the way, at their peak they were shifting enough units and generating enough influence to give Jimi Hendrix and The Supremes a run for their money. But Journey’s Edge is Williamson reaching out to something new, more homespun and – dare one invoke the O-word? – more organic and reaching for things older and more philosophical. Mythic Times captures Williamson claiming again his ancestors of choice and Red Eye Blues his personal Newfoundland while The Maharajah of Mogador is him reclaiming an ancestor for whom he had no choice in the matter, as the said Maharajah came from his wind-up gramophone boyhood. Journey’s Edge is no Childhood’s End. It is no Journey’s End either. It looks to the future. It looks to the past. It is Williamson captured in mid-flight and in trailing-cloud, as they say in Hindlish, air-dash.

December 2006

This is a hitherto unpublished, longer version of some notes written for a reissue that stalled. An expanded edition of Journey’s Edge is available as Fledg’ling FLED 3071 (2008).

More information at www.thebeesknees.com