Shirley Collins and Within Sound (1)

11. 4. 2011 | Rubriky: Articles,CD reviews

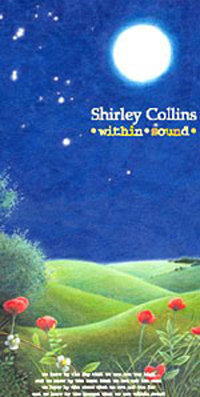

[by Ken Hunt, London] Folksong, English, Czech, Hungarian or any other, is all human life in a nutshell distilled, confined or liberated through song. The Sussex singer Shirley Collins’ achievement is unmatched in the annals of twentieth-century folk music anywhere. Blessed with a voice a natural as breathing, she succeeded in bottling and freeing the essence of the songs she sang. When Shirley Collins’ Within Sound appeared in 2002, the boxed retrospective treatment was a relatively new development in folk music. It is utterly appropriate that Shirley Collins should have been Britain’s first female folk singer to get the long-box treatment. Joan Baez’s Rare, Live and Classic (1993) got the US honours in the female folkie category. Shirley Collins got it with the now sold-out Within Sound (Fledg’ling NEST 5001, 2002).

[by Ken Hunt, London] Folksong, English, Czech, Hungarian or any other, is all human life in a nutshell distilled, confined or liberated through song. The Sussex singer Shirley Collins’ achievement is unmatched in the annals of twentieth-century folk music anywhere. Blessed with a voice a natural as breathing, she succeeded in bottling and freeing the essence of the songs she sang. When Shirley Collins’ Within Sound appeared in 2002, the boxed retrospective treatment was a relatively new development in folk music. It is utterly appropriate that Shirley Collins should have been Britain’s first female folk singer to get the long-box treatment. Joan Baez’s Rare, Live and Classic (1993) got the US honours in the female folkie category. Shirley Collins got it with the now sold-out Within Sound (Fledg’ling NEST 5001, 2002).

Over the course of her eventful career, Shirley Collins, born in August 1935, had any number of peers but very few equals when it came to England’s folk scene and astonishingly few questionable moments on vinyl. She may have experimented with Irish and American song forms early on (though her inflexions wavered at times on say, Jane, Jane on her and Davey Graham’s co-credited Folk Roots, New Route also anthologised on Argo’s spoken word and music set, Voices), but she never dropped her Southern English accent – as if she could ever get Sussex out of her bloodstream. Within Sound made her achievement and progress patently clear. It need not be said, but let’s say it anyway: Fledg’ling Record’ David Suff and Shirley Collins had a huge body of work to draw upon, and a massive task before them, when cherry-picking the performances that made it to final mastering.

For her, part of the joy inherent in the selection process was rediscovering the worth of and joy in what she had done. “I always knew that The Plains of Waterloo was a great song but it’s a great recording of it too. It’s lovely,” she smiles, “that you can still surprise yourself with your own performance. That’s a bonus.”

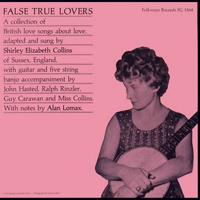

On Within Sound, complementing Collins’ official releases on the Argo, Collector, Deram, Folkways, Harvest, HMV, Island, Polydor and Topic labels, is a smattering of judiciously chosen studio and live performances never, if ever, heard by the wider public, since the day she breathed life into them. Chronologically organised, Within Sound takes the listener on an aural journey from Dabbling In The Dew drawn from the various artists’ anthology Folk Song Today (HMV, 1955), and her double LP debut with Sweet England (1959) for Argo in Britain and False True Lovers (1960) for Folkways in the United States – a phenomenal feat at the time – to Lost In A Wood, drawn from Martyn Wyndham-Read’s brainchild, Song Links (Fellside, 2003), a visionary examination setting British and Australian variants of folksongs next to each other.

On Within Sound, complementing Collins’ official releases on the Argo, Collector, Deram, Folkways, Harvest, HMV, Island, Polydor and Topic labels, is a smattering of judiciously chosen studio and live performances never, if ever, heard by the wider public, since the day she breathed life into them. Chronologically organised, Within Sound takes the listener on an aural journey from Dabbling In The Dew drawn from the various artists’ anthology Folk Song Today (HMV, 1955), and her double LP debut with Sweet England (1959) for Argo in Britain and False True Lovers (1960) for Folkways in the United States – a phenomenal feat at the time – to Lost In A Wood, drawn from Martyn Wyndham-Read’s brainchild, Song Links (Fellside, 2003), a visionary examination setting British and Australian variants of folksongs next to each other.

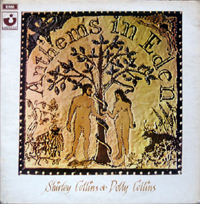

Within Sound contains plenty of the revelations we have come to expect of boxed sets. For example, the run-through of Whitsun Dance – a recording pre-dating her and her arranger-composer sister Dolly Collins’ sessions proper for their 1969 opus magnum Anthems In Eden – is the stuff of dreams. Likewise, the inclusion of her first husband, Austin John Marshall’s song Honour Bright from the never-realised but partially recorded ballad opera The Anonymous Smudge.

As to other comparisons of the creative nature, there is Just As The Tide Was Flowing, as Shirley Collins quips, available “in its three lives” in versions recorded or released in 1959, 1971 and 1979. These were “the straightforward one as we learned from Aunt Grace, then the one with the Albion Country Band and finally a nice arrangement of Dolly’s.” Shirley explains, “That’s an important song because it’s one song that came direct from the family. Nobody else had it [in that version]. If other people sang it they had it in a much rounder form. I still get letters from people saying, ‘You know Just As The Tide Was Flowing; did you know it’s got fourteen more verses?’ My Aunt Grace only knew two verses, so that’s how we sang it.”

Within Sound‘s chronological sequencing makes many things plain, most particularly her development. Beginning near the beginning and treating her first two apprentice pieces, Sweet England and False True Lovers as a single piece of work – they were recorded them back-to-back in one recording session under the watchful eyes of Alan Lomax and Peter Kennedy and then the tracks were divvied up – the listener gets a good feel for the extent of change from one album to the next. Although other work appeared out of sequence, notably the Collins Sisters’ collaboration with the Young Tradition, The Holly Bears The Crown (only finally released in 1995, long after the Young Tradition had broken up in 1969), the official releases between Sweet England and False True Lovers and For As Many As Will (1978) – the final album released under her own name, after which a form of dysphonia stole her singing voice – bear that out.

Between those years, she achieved much of worth. Her second husband, Ashley Hutchings played a prominent part, involving her with the likes of the Morris On bunch, the Etchingham Steam Band, the Albion Dance Band and the Albion Band. Whereas so many folk acts made essentially the same album again and again and again, Shirley Collins showed a steady advance and little or no stylistic repetition once she was recording LPs – and that first release was, remember, in 1959.

She had begun accompanying herself on autoharp or banjo, perhaps augmented with somebody like the physicist John Hasted on guitar. It was all very much in the Fifties’ style of presenting folksong and very much in the stamp of the times. By the time she made The Sweet Primeroses (1967) – ‘primerose’ is a dialect or variant spelling of the commoner ‘primrose’, for the English primrose (Primula vulgaris) – she had five EPs to her name, that collaborative LP with the guitarist Davey Graham (Folk Roots, New Routes, 1964) and a lot of journeyman work to her name and behind her. The Sweet Primeroses was a landmark, not only because it marked the recording debut of her arranger-accompanist-composer sister Dolly on portative pipe organ but because it was one of the albums that stood apart from the trend of the times.

She had begun accompanying herself on autoharp or banjo, perhaps augmented with somebody like the physicist John Hasted on guitar. It was all very much in the Fifties’ style of presenting folksong and very much in the stamp of the times. By the time she made The Sweet Primeroses (1967) – ‘primerose’ is a dialect or variant spelling of the commoner ‘primrose’, for the English primrose (Primula vulgaris) – she had five EPs to her name, that collaborative LP with the guitarist Davey Graham (Folk Roots, New Routes, 1964) and a lot of journeyman work to her name and behind her. The Sweet Primeroses was a landmark, not only because it marked the recording debut of her arranger-accompanist-composer sister Dolly on portative pipe organ but because it was one of the albums that stood apart from the trend of the times.

Whereas the popular face of folk was the smiles and serious faces of television’s Julie Felix, the Spinners and their ilk, Shirley sang Sussex; much like the Watersons sang Yorkshire or Harry Boardman sang Lancashire. A year on and Shirley Collins was making The Power of the True Love Knot (1968), still credited solely to her but with Dolly’s adventuresome arrangements and accompaniments ever more to the fore.

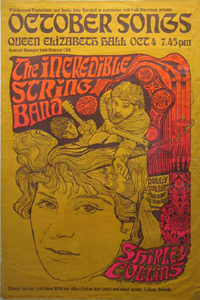

Dolly Collins defined her approach succinctly to me in 1979 for an article in Swing 51: “Let the music be suited to the people [the audience] rather than the people be ‘trained’ to the music”; these were words that her teacher, the composer and doyen of the Workers’ Music Association Alan Bush (1900-1995) might have dictated to her. The Power of the True Love Knot‘s opener, Bonnie Boy uses the cello of Bramwell ‘Bram’ Martin, the cellist on the Beatles’ Eleanor Rigby and She’s Leaving Home but also a mainstay of the ‘Mantovani Sound’, as a colour instrument while Mike Heron and Robin Williamson of the Incredible String Band did their finger-popping stuff on the bonnily romantic, let’s-outdo-Mills & Boon Ritchie Story. (Both tracks are fragrances on Within Sound.) By now, you realised that you were somewhere completely unimaginable at the time of Sweet England. This is less surprising when you know that Austin John Marshall was an early advocate of Jimi Hendrix and had taken Shirley off to see him early on. It was a period of exemplary artistic foment.

Next she asked her audience to take a deep breath and a leap into the unknown with Anthems In Eden. 1969 was the year of Martin Carthy and Dave Swarbrick’s defining Prince Heathen, Ralph McTell’s Spiral Staircase, Judy Collins’ Who Knows Where The Time Goes, Joan Baez’s Any Day Now, Fairport Convention’s Liege and Lief, and the Spinners’ never-better-titled Not Quite Folk. The Sisters’ Early Music, big band album stood out and apart from the throng. Furthermore, it was released in the launch year of EMI’s ‘progressive’ label Harvest. It would sit alongside era-defining work by Pink Floyd, Forest, the Edgar Broughton Band and Deep Purple. Its first side, a complete song-cycle, had first been aired on BBC Radio 1’s My Kind of Folk in August 1968 with the Home Brew and the Dolly Collins Harmonious Band supporting. This, the first of two albums for the ‘underground label’, reached places and audiences denied Radio 1.

Next she asked her audience to take a deep breath and a leap into the unknown with Anthems In Eden. 1969 was the year of Martin Carthy and Dave Swarbrick’s defining Prince Heathen, Ralph McTell’s Spiral Staircase, Judy Collins’ Who Knows Where The Time Goes, Joan Baez’s Any Day Now, Fairport Convention’s Liege and Lief, and the Spinners’ never-better-titled Not Quite Folk. The Sisters’ Early Music, big band album stood out and apart from the throng. Furthermore, it was released in the launch year of EMI’s ‘progressive’ label Harvest. It would sit alongside era-defining work by Pink Floyd, Forest, the Edgar Broughton Band and Deep Purple. Its first side, a complete song-cycle, had first been aired on BBC Radio 1’s My Kind of Folk in August 1968 with the Home Brew and the Dolly Collins Harmonious Band supporting. This, the first of two albums for the ‘underground label’, reached places and audiences denied Radio 1.

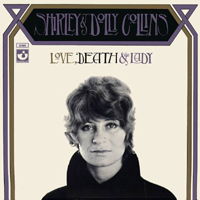

Creatively it was a high water mark that she wisely never attempted to reach again. That was not in her nature. Beside the buoyancy and big-budget values of Anthems In Eden, Love, Death & The Lady (1970) seemed a bare affair, reflecting in part its leading ladies’ wretchedness in matters of the heart. Plains of Waterloo captures a rarely paralleled quality of a sombre bleakness and hopelessness. Following Love, Death & The Lady, she returned with No Roses (1971), co-credited to the Albion Country Band, an album with a crew of folk-rock and wayward folk alumni that included Ashley Hutchings on bass, Dave Mattacks on drums, Richard Thompson on guitar, vocalists Maddy Prior (of Steeleye Span) and Royston Wood (late of the Young Tradition), Lal and Mike Waterson. By Adieu To Old England (1975) and For As Many As Will (1978), Shirley and Dolly Collins had gone back to acoustically rooted sensibilities. If the listener picks three (or five) of these albums sequentially starting anywhere in the chronological order, the degree of stylistic difference is astounding. The one constant is her voice. It rarely veered from its Sussex roots.

Creatively it was a high water mark that she wisely never attempted to reach again. That was not in her nature. Beside the buoyancy and big-budget values of Anthems In Eden, Love, Death & The Lady (1970) seemed a bare affair, reflecting in part its leading ladies’ wretchedness in matters of the heart. Plains of Waterloo captures a rarely paralleled quality of a sombre bleakness and hopelessness. Following Love, Death & The Lady, she returned with No Roses (1971), co-credited to the Albion Country Band, an album with a crew of folk-rock and wayward folk alumni that included Ashley Hutchings on bass, Dave Mattacks on drums, Richard Thompson on guitar, vocalists Maddy Prior (of Steeleye Span) and Royston Wood (late of the Young Tradition), Lal and Mike Waterson. By Adieu To Old England (1975) and For As Many As Will (1978), Shirley and Dolly Collins had gone back to acoustically rooted sensibilities. If the listener picks three (or five) of these albums sequentially starting anywhere in the chronological order, the degree of stylistic difference is astounding. The one constant is her voice. It rarely veered from its Sussex roots.

For more information go to www.shirleycollins.co.uk

Small print

The copyright of all other images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers. Unless otherwise stated, all interview material is original and copyright Ken Hunt.