Shirley Collins and Within Sound (2)

18. 4. 2011 | Rubriky: Articles,CD reviews

[by Ken Hunt, London] In this second part we pick up the story of the out-of-print classic retrospective Within Sound at a point after the 1970 masterpiece Love, Death & The Lady (1970).

[by Ken Hunt, London] In this second part we pick up the story of the out-of-print classic retrospective Within Sound at a point after the 1970 masterpiece Love, Death & The Lady (1970).

Despite everything in the years from 1955, when Shirley Collins had first appeared on record, to 1970 , there was no grand plan behind the continually shape-shifting projects that she was delivering. “I have to say,” she explains. “it ‘happened’ rather than it was planned in advance that one would do something different the whole time. Things did evolve. It was the discoveries. It was those fortunate meetings. It was my own interests in the sorts of music I liked listening to – Early Music, for example – that led me into these other things. In a way it did just grow. It wasn’t planned but it wasn’t willy-nilly. There was obviously a great deal of thought involved with each record once we decided to do the recording we were doing. I think it’s possibly because my personal life and my singing life were so bound up that whatever was going on in my life was reflected in the records as well. The influences, the things that were happening, the people I met as I went along… It’s all rather fortunate the way things happened. Like finding the Early Musicians in Musica Reservata and meeting David Munrow. But then, I suppose, it was having the wit to think that this and that would work together. With part of the early stuff it was John Marshall who thought that we could do it; it was Dolly who wrote the stuff and made it happen with her arrangements; and it was my ear and my own inclinations to do the best for the music.

Despite everything in the years from 1955, when Shirley Collins had first appeared on record, to 1970 , there was no grand plan behind the continually shape-shifting projects that she was delivering. “I have to say,” she explains. “it ‘happened’ rather than it was planned in advance that one would do something different the whole time. Things did evolve. It was the discoveries. It was those fortunate meetings. It was my own interests in the sorts of music I liked listening to – Early Music, for example – that led me into these other things. In a way it did just grow. It wasn’t planned but it wasn’t willy-nilly. There was obviously a great deal of thought involved with each record once we decided to do the recording we were doing. I think it’s possibly because my personal life and my singing life were so bound up that whatever was going on in my life was reflected in the records as well. The influences, the things that were happening, the people I met as I went along… It’s all rather fortunate the way things happened. Like finding the Early Musicians in Musica Reservata and meeting David Munrow. But then, I suppose, it was having the wit to think that this and that would work together. With part of the early stuff it was John Marshall who thought that we could do it; it was Dolly who wrote the stuff and made it happen with her arrangements; and it was my ear and my own inclinations to do the best for the music.

“In a way it harks back to what Alan always believed. Alan Lomax always believed that you put the best at the disposal of the people you were recording. He went for the best: the best technical quality you could get, the best recording equipment – and it was being improved the whole time. He always had to do the best for the people that he was recording. And I always felt that I had to do the best for the music. The best was, in many cases, to get a perfect accompaniment. Or if not perfect, an appropriate accompaniment for this lovely music that had been neglected for so long. I was fortunate to have a sister that could write it, and people around me that were encouraging. God knows, it didn’t get a lot of encouragement but there were key people!”

She volunteers their names without prompting. “I was fortunate to meet Lomax in the first place. John Marshall was another. He supported and encouraged me, and was always trying to find other ways of doing things – although they were tiresome at times as well. He was always willing and open to try things. I was fortunate later to meet Ashley. I was fortunate to have David Tibet come on the scene; he put out the first compilation of the Topic stuff. I was incredibly fortunate to have David Suff as a champion. I was absolutely blessed with these keen figures but then I also think they were also blessed with me.”

She volunteers their names without prompting. “I was fortunate to meet Lomax in the first place. John Marshall was another. He supported and encouraged me, and was always trying to find other ways of doing things – although they were tiresome at times as well. He was always willing and open to try things. I was fortunate later to meet Ashley. I was fortunate to have David Tibet come on the scene; he put out the first compilation of the Topic stuff. I was incredibly fortunate to have David Suff as a champion. I was absolutely blessed with these keen figures but then I also think they were also blessed with me.”

Recovering from a small fit of the giggles, she continues, “I’ve stopped being so modest nowadays because when I listen to the stuff I know it’s so good. I’m not going to sit back and pretend that it’s not now.”

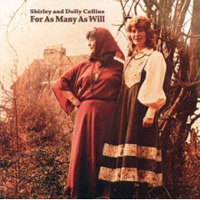

Part of the problem to do with her phasing out performing in public was a loss of confidence. In 1978 Topic released For As Many As Will, co-credited to her sister Dolly. Two years later on an Australian tour in early 1980, a double-hander with Peter Bellamy (formerly of the Young Tradition), she plagued herself with doubts – and self-inflicted doubts are amongst the worst . It had further repercussions for her singing. She remembers Australia as “being a terrifying ordeal because I didn’t have Dolly and I was losing my voice. It was part of this slow process of everything going and the more I did the more afraid I became. The Sydney Opera House was terrifying. When I listened to Come, My Love it was absolutely gorgeous. There was Dolly’s wonderful arrangement played with such bravura on the harpsichord by Winsome Evans that I thought, ‘You were all right, you could have kept on doing this, Shirl!’ But I didn’t hear this at the time. I wasn’t aware at the time that it was more than OK. I let myself believe that I was no good anymore. I loved English music and I wanted to be a singer of English songs. However hard it got, I never gave in. Until things got too impossible for me to be able to sing, that is. By that time, I’d already virtually done it really, I think against all the odds. I hoodwinked myself. Or perhaps I punished myself.”

Part of the problem to do with her phasing out performing in public was a loss of confidence. In 1978 Topic released For As Many As Will, co-credited to her sister Dolly. Two years later on an Australian tour in early 1980, a double-hander with Peter Bellamy (formerly of the Young Tradition), she plagued herself with doubts – and self-inflicted doubts are amongst the worst . It had further repercussions for her singing. She remembers Australia as “being a terrifying ordeal because I didn’t have Dolly and I was losing my voice. It was part of this slow process of everything going and the more I did the more afraid I became. The Sydney Opera House was terrifying. When I listened to Come, My Love it was absolutely gorgeous. There was Dolly’s wonderful arrangement played with such bravura on the harpsichord by Winsome Evans that I thought, ‘You were all right, you could have kept on doing this, Shirl!’ But I didn’t hear this at the time. I wasn’t aware at the time that it was more than OK. I let myself believe that I was no good anymore. I loved English music and I wanted to be a singer of English songs. However hard it got, I never gave in. Until things got too impossible for me to be able to sing, that is. By that time, I’d already virtually done it really, I think against all the odds. I hoodwinked myself. Or perhaps I punished myself.”

Going through the possible material for inclusion on Within Sound no longer involved breast- or brow-beating. The passage of the years had taught her the lesson not to judge herself as harshly as once she had. “There were certain things, like The False True Love that I’d recorded twice in my life, where I thought how brave a performance it was when I listened to it. That was the actual word. I hold one note and it just goes on. I was always in love or suffering. I think it has the essence of young, unrequited love in it. I thought, ‘God, that’s a brave performance!'”

This process of rediscovery threw up several insights too. “There are other things that you listen to – Poor Murdered Woman, which I think is one of the great tracks – which have great passion in them. It’s not so passionate that it’s dramatised. The passion is within the song itself. It’s a very restrained sort of passion. When I hear Poor Murdered Woman I think, that’s good. There are so many funny things too. Like, when you listen to Fare Thee Well, My Dearest Dear there’s Ashley’s bass louder than my voice. And I think that’s fairly typical. It makes me laugh but I had to put it on the boxed set because that’s such an important song to me and Harriet Verrall of Monksgate was such an important singer to me.”

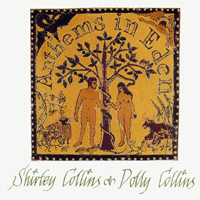

With Within Sound surprises came in other packages too. One of the pieces that rings so sonorously down the years is the unearthing of Whitsun Dance. Unlike the ‘big band’ rendition from the finished Anthems In Eden (1969), on the boxed set she sings it alone with her sister accompanying on piano. Adding an insight into the creativity, it wafts in the refreshing tang of something familiar yet somehow unfamiliar. “That was obviously a trial recording of the piece. I didn’t know I had it. It came from the cupboard under the stairs. I got a box of tapes and we kept looking and looking. There was this thing that said Whitsun Dance. I thought it was bound to be an Anthems track. It was recorded in the studio, I don’t remember for certain, a day or so before. It is lovely. I was so thrilled when I heard it because it has a different quality and a slightly different lift to the tune. I hadn’t realised what I’d done. I was so thrilled by that little discovery. It’s only a slight difference but it’s a huge difference.”

With Within Sound surprises came in other packages too. One of the pieces that rings so sonorously down the years is the unearthing of Whitsun Dance. Unlike the ‘big band’ rendition from the finished Anthems In Eden (1969), on the boxed set she sings it alone with her sister accompanying on piano. Adding an insight into the creativity, it wafts in the refreshing tang of something familiar yet somehow unfamiliar. “That was obviously a trial recording of the piece. I didn’t know I had it. It came from the cupboard under the stairs. I got a box of tapes and we kept looking and looking. There was this thing that said Whitsun Dance. I thought it was bound to be an Anthems track. It was recorded in the studio, I don’t remember for certain, a day or so before. It is lovely. I was so thrilled when I heard it because it has a different quality and a slightly different lift to the tune. I hadn’t realised what I’d done. I was so thrilled by that little discovery. It’s only a slight difference but it’s a huge difference.”

What emerges over the course of Within Sound is the distillation of something uniquely English. Folksong isn’t everybody’s cup of tea – nothing is, thank goodness – but some of that is because too many people have come to the table with their minds made up about singers with cupped hand over the ear. (Far from being folk’s exclusive domain or folly, it is a technique used in voice projection round the globe.) Naturally, folksong must have had its moments of Moon-in-Junery but folk music’s oral process is an extremely efficient way of disposing of banality as well as preserving the stuff that touches the soul. After all, a shit song need not be a shit song forever; it can be relegated to the antiquarian’s back pages and quietly parked. It’s the good stuff that we remember and that is what we need to remember.

With Within Sound, part of England’s rich folk tradition began to receive the attention it deserves.

A coda

A coda

Harriet Verrall, it should be explained, was the original source of Poor Murdered Woman on Shirley Collins and the Albion Country Band’s No Roses (1971) and the well-known tune to Our Captain Cried All Hands, a piece of music that Ralph Vaughan Williams re-christened Monksgate when setting John Bunyan’s rousing school assembly ‘favourite’, He Who Would Valiant Be in The English Hymnal published in 1906 for the Church of England under the editorship of Percy Dearmer and Ralph Vaughan Williams. Parethetically, the whole Verrall-Vaughan Williams axis figures in her recent talk A Most Sunshiny Day that she performs with actor-singer Pip Barnes.

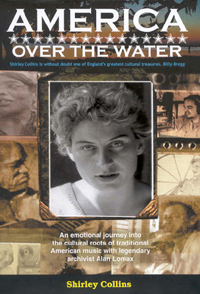

Although she lost her singing voice, she bounced back with a series of talks that range over her work with Alan Lomax (also the subject of her autobiographical account of their 1959 music-collecting trip America Over The Water (2004)), accounts of Southern English Gypsies and, as ever with Pip Barnes, supporting Martyn Wyndham-Read in his account, Down The Lawson Trail – his portrait in words and song of the Australian writer and bush poet Henry Lawson (1867-1922).

For more information go to www.shirleycollins.co.uk

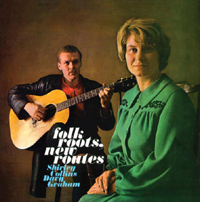

Ken Hunt is the author of the biographical essays about Dolly Collins (1933-1995) and Davey Graham (1940-2008) in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Small print

The copyright of all other images lies with the respective photographers, companies and image-makers. Unless otherwise stated, all interview material is original and copyright Ken Hunt.