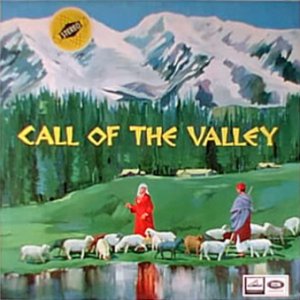

Shivkumar Sharma, Brijbushan Kabra and Hariprasad Chaurasia’s The Call of the Valley II

1. 6. 2009 | Rubriky: Articles,CD reviews

[by Ken Hunt, London] Key works that open doors to reveal unsuspected possibilities are fewer and farther between than press releases and other fictions would lead us to believe. On the basis that a little hyperbole goes a long way, glib judgements get bandied around with frightening frequency and lightning strike effect. For many people Call of the Valley opened up the skies, was a revelation. Its impact could be likened to revealing a new colour in the spectrum, for it was directly responsible for bringing Hindustani classical music – as Northern Indian classical music is known – to new audiences all around the globe. Its three soloists would go on to internationally acclaimed careers. But all that lay in the future. For countless listeners the first time they would hear the consummate musicianship of Shivkumar Sharma, Brijbushan Kabra and Hariprasad Chaurasia would be this record.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Key works that open doors to reveal unsuspected possibilities are fewer and farther between than press releases and other fictions would lead us to believe. On the basis that a little hyperbole goes a long way, glib judgements get bandied around with frightening frequency and lightning strike effect. For many people Call of the Valley opened up the skies, was a revelation. Its impact could be likened to revealing a new colour in the spectrum, for it was directly responsible for bringing Hindustani classical music – as Northern Indian classical music is known – to new audiences all around the globe. Its three soloists would go on to internationally acclaimed careers. But all that lay in the future. For countless listeners the first time they would hear the consummate musicianship of Shivkumar Sharma, Brijbushan Kabra and Hariprasad Chaurasia would be this record.

Shivkumar Sharma, Brijbushan Kabra and Hariprasad Chaurasia were all aged about 30 when they convened to make Call of the Valley. Shivkumar Sharma, who had made his first solo album in 1960, had worked to raise the status of the santoor to that of a respected classical concert instrument. A trapezoid-shaped member of the hammer dulcimer family, his santoor is modified to bear 87 strings arranged in 29 triplets of strings, each triplet tuned to the same note. The strings are struck with two mallets called qalam made of a hardwood such as walnut. In his native Jammu and Kashmir, where it is used to accompany a regional music called sufiana mausiqi or its poetic counterpart called sufiana kalaam, the santoor has 100 strings, albeit differently configured. Although its Persian relative, the santur, has long associations with Persian and Iranian classical music, Shivkumar Sharma’s decision to elevate such a lowly folk instrument to the concert platform was viewed as folly in conservative quarters.

Call of the Valley, in the opinion of Shivkumar Sharma and many other people, was responsible for establishing and popularising the instrument in Hindustani classical circles. It would decisively silence the critics. In 1967, however, it was an altogether different story. Brijbushan Kabra’s instrument was the guitar, another instrument that was having to prove itself because of its non-classical and western associations. Hariprasad Chaurasia was in the process of establishing himself as a flautist. His choice of the bansuri, a bamboo transverse flute, presented other problems. The flute is not just popular, it is of religious significance to the Hindu faith. In the 1960s memories of the flute virtuoso Pannalal Ghosh – he died in 1960 – were fresh. Hariprasad Chaurasia had to brave and convince the conservative wing of Hindustani music. The success of this album would place all three musicians on the musical map.

In 1967 the concept behind Call of the Valley broke new ground. While staying true to Hindustani tradition, it also captured a freshness and a timelessness. Conceived as a suite, Call of the Valley wove a story about a day in the life of two lovers in Kashmir. Santoor, guitar and flute were the voices that told the story. Underlying the tale was something that was as simple as it was radical. Shivkumar Sharma’s proposal was to make use of one of the basic organisational principles of the Indian raga – or rāg – system. The raga – “that which colours the mind” is a poetic description often applied – is the melodic heart of Indian music. For centuries music theoreticians have classified ragas in various ways, associating them with a particular season or time of the day according to their characteristics and mood. Talking to me in April 1987 Shivkumar Sharma sketched how this relationship works: “For early morning we have a raga that expresses a particular mood. In the daytime different ragas are played. They’re connected with Nature. How do you feel when the sun rises? You have a particular feeling when you see full moonlight. You react to Nature in different ways. Our ragas are connected with that and each raga expresses a different mood.”

“You know,” he reflected looking back on the project in June 1994, “when I was asked to do this recording and I thought about its theme, I wanted to have classically based ragas and convey them through a story. What I thought was we should weave a story around these rāgs as we had a time period that started with sunrise and afternoon through to evening and late evening and all that. I had one sketch in mind. I thought about a story and I discussed it with Mr. G.N. Joshi. I told him how I wanted to project the story.”

Classics are not magicked out of the ether and Shivkumar Sharma’s fantasia needed further definition and substance. But G.N. Joshi, the writer of the original sleeve notes, intuitively grasped the concept and gave the budding project the green light. “When I thought of this idea, when I thought of these two characters, one male and one female, and of Nature, I felt I should have a few more instruments. Naturally when I thought about it, I thought about my friends Hariprasad Chaurasia and Brijbushan Kabra, because if you want to create music together it is essential that you know the person, know the musician personally. We were friends. I naturally thought of them. I felt the guitar could express the mood of a male character, the santoor of a female character. The flute could express what Nature is and what a person feels about natural surroundings. When I talked to them they liked the idea very much. We knew we could work together very easily.

“We arrived at the whole synopsis of the story, so to speak, and how to proceed. We started with Rāg Ahir Bhairav and then Nat Bhairav and then there was a composition in Rāg Piloo. After Piloo we had Bhoop and then there was some composition based on Des. The last one was Pahadi, based on a folk song. After we were clear about all these ragas and compositions and how we would proceed and how each instrument would be involved in that, when the whole thing was ready, I again had discussions with Mr. G.N. Joshi and explained to him how I conceived this idea, how I felt about it. He explained the whole thing – which was the sleeve notes – the story about how a shepherd’s day goes and what each instrument was conveying.”

G.N. Joshi’s very presence at the sessions was a kind of validation. He would become the de facto producer of the album – albeit uncredited – as Shivkumar Sharma explains: “He was in charge of the recording section [at the Gramophone Company of India in Bombay]. I don’t know the terminology and what exactly his designation was but he was in charge. He used to be responsible for getting all these recordings done. He used to be responsible for engaging the musicians, getting the recordings done. He was the producer of that recording, a kind of producer.”

Because he was a key player in this Kashmiri drama, it is useful to capture a flavour of how respected G.N. Joshi was. Born in 1909, Govindrao Joshi was a singer. In 1930, as he wrote in Down Memory Lane, his account of a career in music, he received an invitation to broadcast from a Bombay radio station. The broadcast took place on New Year’s Day, 1931 and was well received. Which was how he came to record for HMV (His Master’s Voice), one of the names that the Gramophone Company of India traded under in those days. His setting of N.G. Deshpande’s Marathi poem Sheel (‘The Whistle’) – G.N. Joshi’ mother tongue was Marathi – proved particularly popular in Maharashtra. More recording sessions followed. By 1936 Joshi’s reputation could sustain a four-month tour of British East Africa, including Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika and Zanzibar. Yet, like the dutiful son that he was, parallel with his singing career he had gone about getting himself pukka qualifications. In due course he was practising law. But music was his first love and he jumped at an offer to work full time as a recording executive for HMV in Bombay. He started on the first day of June 1938.

It was a post he would hold for 34 years. During that time G.N. Joshi would preside over many of the most historic sessions in Indian classical music. Call of the Valley was but one of the seminal sessions he helped to shape. At one extreme he would record a variety of important Marathi actor-singers whose work, he tells, was the living embodiment of literary high-browism. At another, more humdrum extreme, he was responsible for recording politicians’ speeches, singer-propagandists extolling the alcohol prohibition in force in the early 1950s, and government exhortations to open small savings accounts. Visionaries, and G.N. Joshi was one, also have to deal with the mundane. More relevantly, he was also personally responsible for a catalogue of magnificent artistry. Among the legendary vocalists he recorded were Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan and his brother Ustad Barakat Ali Khan, Pandit Omkarnath Thakur, D.V. Paluskar, Ustad Amir Khan, Dr. Kumar Gandharva, Surashri Kesarbai Kerkar, Begum Akhtar and Pandit Bhimsen Joshi. He also preserved the work of masters such as Pannalal Ghosh, the multi-instrumentalist Ustad Allauddin Khan and his son, the sarod virtuoso Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, the tabla maestros Ustad Amir Hussain Khan, Ustad Ahmad Jan Tirakhwa and Ustad Alla Rakha, and the sitar virtuoso Ustad Vilayat Khan. By preserving many of Hindustani music’s most colourful vocalists and instrumentalists G.N. Joshi helped to shape and shade the future appreciation of Indian music. He was present at a pivotal time in Hindustani music. The old master-pupil tradition of handing on knowledge was under severe pressure and in decline. The World of Indian Arts will be forever in his debt.

Not for nothing then was Shivkumar Sharma delighted to have G.N. Joshi’s blessing. “This was a very novel idea at that time,” Shivkumar Sharma remarked. “Nobody had tried in Indian classical music a theme like that, trying to express a story-like theme. Mr. Joshi was himself a musician. It was very important that he could understand what we were doing.

“Normally what happens is that if a person is working with a record company he is not knowing music. It’s difficult to work or get things done together. If he happens to be a musician – like Mr. Joshi was – things can be very easy. We could understand each other and work things out together. He knew many great musicians like Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khansahib, Ustad Amir Khan and Pandit Omkarnath Thakur because he had been involved with all the recordings of HMV in those days.”

Their session with G.N. Joshi took place over the course of one night in HMV’s studio in Bombay. In addition to the three main voices of guitar, flute and santoor, Manikrao Popatkar played tabla. Typically for the period the original LP credits were incomplete. Shivkumar Sharma was able to clarify some things from memory. “Rijh Ram played pakhawaj [a two-headed barrel drum] as well as swarmandal. There were some other effects – bells and small effects – that were made by some musician from HMV.” (The latter’s name has gone unremembered.) “We did two or three days’ rehearsal together. Of course, everything was not fixed. We just fixed the compositions in the ragas and for the rest of it we just had tentative ideas of the timings. The recording was done in one day. We went in the studio in the evening and we worked till next morning. I don’t think we had to repeat many things or that there were cuts in the recording. We finished it in one session.”

Call of the Valley clearly found a commercial as well as an aesthetic niche because, unusually, the Gramophone Company of India never let it drop from the catalogue. A colleague at the company’s London office told me it even turned up in CD counterfeiting raids in Britain in 1994 – an accolade of the backhanded sort for a classical recording. Part of its appeal lay in the ease with which it engaged the listener, irrespective of their cultural background. “In India itself many people who were not interested in Indian classical music at all, they got interested in Indian classical music after listening to this record. Then they started listening to other things also. The same thing happened in America and in many of the European countries which I came to know later on when I used to go on tour. Many people even now meet me and tell me that they had not been exposed to Indian classical music, were never interested in it before but after listening to Call of the Valley they got interested and were attracted to these sounds.”

For time out of mind people have suspended critical judgement and emptied their minds to chant somebody else’s First Law of Self-promotion. Law or mantra, it goes, ‘The latest is the best.’ Consequently so much that is insubstantial gets hailed as an instant classic in the compulsion to laud the new to the skies. Call of the Valley was a historic landmark in the popularisation of Hindustani classical music. A benchmark of excellence, time has shown how important and how innovative its vision was. Call of the Valley has truly earned its status of classic. ‘Classic’ is a much abused word but it applies to Call of the Valley.

A version of this essay – and its first part – appeared in 1995 with the dedication: “For G.N. Joshi for Ustad Amir Khan’s Marwa, Call of the Valley and others yet to discover, my father Leslie Lloyd Hunt who put me on the path of music, for my uncle Alec Frederick Hunt who acquainted me with the correlation of culture, history and politics, and for Shivkumar Sharma for opening so many minds.”