Sketches of American Counterculture – Laurie Anderson. Allen Ginsberg. Philip Glass.

17. 10. 2011 | Rubriky: Articles

[by Ken Hunt, London] Let’s start metaphorical. Maybe poetical and ecological too. Counter-culture in the 1960s was like alternative now, like spring-water welling to the surface and forming rivulets. Streams and rivers form, few with fixed shapes. Currents change unpredictably. Some silt or dry up or form ox-bow lakes. Others keep on flowing and joining up. Counter-culture and alternative have something else going for them. Without getting rheumy-eyed, it’s like great river junction at Prayaga – Hinduism’s Allahabad – where the Ganges and Jamuna meet the invisible Sarasvati. Like Prayaga, they are where the seen and the spiritual meet in a great confluence.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Let’s start metaphorical. Maybe poetical and ecological too. Counter-culture in the 1960s was like alternative now, like spring-water welling to the surface and forming rivulets. Streams and rivers form, few with fixed shapes. Currents change unpredictably. Some silt or dry up or form ox-bow lakes. Others keep on flowing and joining up. Counter-culture and alternative have something else going for them. Without getting rheumy-eyed, it’s like great river junction at Prayaga – Hinduism’s Allahabad – where the Ganges and Jamuna meet the invisible Sarasvati. Like Prayaga, they are where the seen and the spiritual meet in a great confluence.

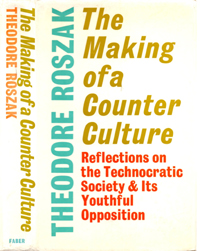

Theodore Roszak’s 1969 book The Making of a Counter Culture – Reflections on the Technocratic Society & Its Youthful Opposition was the first major attempt to examine and contextualise the movement and, importantly, its historical continuum. At one point he observes how, “Shelley’s magnificent essay ‘The Defence of Poetry’ could still stand muster as a counter cultural manifesto.” Counter-culture had everything to do with what Patti Smith calls “chosen ancestors”. Percy Bysshe Shelley is still a chosen ancestor, waiting in the wings to come on. The first time I met Ginsberg he was returning from a visit to a Southern English place with William Blake associations. The last time we met he gave an impromptu performance of Shelley’s poem The Mask of Anarchy; it was so gloriously approximate, it amounted to a rewrite. When it comes to choosing ancestors, wit lies in not in fabricating genealogy but what you do with the legacy.

Historically, personal recommendation was the main way of tuning in and turning on to new experiences. Through word of mouth, reading and listening you made connections. In that pre-internet age, it was linking finding a rope at night. It was only come daylight that you started to get a proper feel for how far back it stretched and how varicoloured the rope’s strands were. Nowadays it’s easier and more difficult. Once the difficulty was accessing information. Now, it’s information overload. Although a title like Sketches of American Counterculture requires a New World focal point, bear in mind that rope stretched right round the globe.

So you read Kerouac and he connects with Ginsberg, Corso, Ferlinghetti, Burroughs and Slim Gaillard. You discover Bob Dylan and you see the names Eric von Schmidt and Martin Carthy on the backs of LPs. More recommendations. Avant-garde composers John Cage and Lou Harrison steer you to Colin McPhee, Henry Cowell and Philip Glass. Or you discover Alla Rakha and Ravi Shankar and get to Glass by a non-minimalist route. There are many routes. (Shankar’s original overseas audiences came via Satyajit Ray’s films and the jazz and folk scenes before the Beatles.) Eventually you have a countercultural rope trick.

You join up the microdots and the connections are infinite. Steve Reich, Pauline Oliveros, the Grateful Dead, Country Joe and the Fish all have connections with the San Francisco Mime Troupe. Likewise, Burroughs connects with Laurie Anderson, David Bowie, Paul Bowles, Lou Reed and on and on and back to Patti Smith’s “chosen ancestors. Or to digress outside the arts, in 1962 you read Rachel Carson’s environmental wake-up call about the agrochemical impact on the food chain, Silent Spring and that leads to further alternative discoveries about what food you are eating and to organic gardening, ecology and the environment. These Sketches focus on the arts, but when did you last meet anyone artistic who doesn’t eat?

Counter-culture’s great confluence of ideas bust open many a mind-dam. Yet, as citing Shelley suggests, it never sprang fully formed. It came with historical forebears. It drew on earlier bohemian, artistic and radical antecedents. It built on dissenting, freethinking traditions. It suggested political, belief system or humanist ethics. It even responded to mainstream society legalising the forbidden or redefining the rules. North America may have its well-known traditions of polygamy or polyamory but so did Germany. Had history lessons about the 30 Years War recalled the Church’s injunction to good god-fearing Germans to take 10 wives in order to repopulate congregations, I might have paid more heed. Mind you, you were probably never taught about the English Revolution with its radical organisations like the Levellers, Ranters and Diggers – resurrected in San Francisco in the 1960s – or British republicans celebrating 30 January 1649. So we’re quits.

What I remember best – or choose to remember the most – is the Counter-culture’s open-mindedness, its invitation to examine conformities and expand minds. Of course, it had hedonistic moments and peddled derangements of the mind. (They weren’t all bad either.) It’s just such a pity the Counter-culture got saddled with such a shitty name. The dead hand of etymology weighs it down. Unlike the old Johnny Mercer and Harold Arlen lyric, counter-culture accentuates the negative with its ‘contra’ and ‘against’ associations. When counter-culture entered everyday speech in the 1960s, it was laden with all manner of negative baggage. On balance, its positivity outweighed the negative. The movement itself was more pro than anti. Alternative accentuates the positive better. Anyway, I’m still finding new chosen countercultural ancestors. Or getting to know them better. I suspect the day I stop I’ll be dead.

This is a version of a German-language essay published in the programme to TFF Rudolstadt in 2007. This essay is published here for the first time in English in memory of Theodore Roszak (1933-2011).