Ralph McTell – On songs, recording, Nanna’s Song and Streets of London

2. 4. 2010 | Rubriky: Articles,Interviews

[by Ken Hunt, London] Ralph McTell is one of Britain’s foremost commentators on the national condition using demotic idioms – folk, blues, ragtime. Rather like Wolf Biermann, Franz-Josef Degenhardt and Christof Stählin in Germany (and then add your own regional or national candidates), he has depicted his homeland through music, through songs, that meanings of which seem immediately apparent but which may well prove to be more eely or oblique.

[by Ken Hunt, London] Ralph McTell is one of Britain’s foremost commentators on the national condition using demotic idioms – folk, blues, ragtime. Rather like Wolf Biermann, Franz-Josef Degenhardt and Christof Stählin in Germany (and then add your own regional or national candidates), he has depicted his homeland through music, through songs, that meanings of which seem immediately apparent but which may well prove to be more eely or oblique.

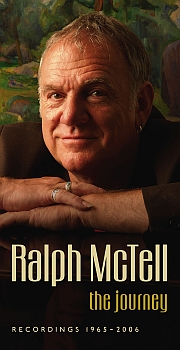

This snippet is drawn from a long interview conducted in September 2006 for an article that appeared at the time of the release of the self-effacing man’s 4-CD boxed set, The Journey – Recordings 1965-2006 (Leola OLABOX60) that David Suff put together for the label.

True to his roots, McTell booked a folk club gig at Twickfolk @ the Cabbage Patch Pub in Twickenham, Middlesex in March 2010, prompting this morsel.

What did you learn about your own creative process from The Journey?

Very good question. I think we have to go back to my perceived role for myself. I think that it is not a keeper of the scrolls or the tradition, or a protector of the tradition; it is the belief that there is a basic honesty in one man and a guitar if the subject matter is right. My stimulus is drawn from men and women who appeared to do that for me. All, I think, I sought to do while I was doing that, was to get better at what I was doing. Which is partly to enjoy and to discover the music myself and to exploit what little I have or what my offering could be and to try to improve. But not to lose sight entirely of what first motivated me. The odd excursion I have made into a broader folk-rock field or whatever was all done with the same intent. The idea of doing songs in the main still had to fit those criteria.

Listening back [to The Journey], it’s not as good as what I hoped at the time. Considering I’m a very bad recording artist. I’ve had a 40-year career, sometimes I say in spite of my recordings! I’m not at ease in the studio. I don’t like recording studios. I don’t enjoy recording and I don’t particularly enjoy listening to my own records. But I enjoy the process of creating. I leave the ‘studio bits’ to other people. I have managed to develop the rather useless talent of hearing what I want to hear when I’m listening to playback. I’m not as hard enough on myself, on mixes and on performances as I should be.

When I was working with a producer like Gus Dudgeon who sought perfection at every level, he must have despaired of me. We parted company on the basis that I couldn’t keep repeating performances. Since I have liberated myself from that by doing only live vocals and only one or two takes I’m much happier with those recordings that have gone back to the basic honesty of those first recordings by other people that I love.

So, that’s what I’ve learnt. I’ve learnt, one, that there’s nothing wrong with the odd foible, dodgy note, slightly sharp, breathless, more moved than moving – as my manager once said to me – and gone for the way Bob [Dylan] does it. I’m not blessed with a voice that can soar and rise and do the things that Bob can do in his individual performances, but my voice has grown, has got broader, wider, deeper, whatever. I’m as sincere as I ever was. I trust my 40 years of guitar playing and singing to get a reasonable performance down in the studio.

But to say I’m a fan of my own records is not true. I can be delighted with other people’s performances but they’re very wordy songs, so I don’t often give a lot of room for other people to blow or to play over. They’re there to enhance the song and to fill out what I hear in my head within the chord structure that I’ve created.

How do you feel about your personal progress? For instance, you have a song on the boxed set to do with your wife, Nanna. You have a very early recording of Nanna’s Song [from Eight Frames A Second, 1968] and you have a much later one [from Travelling Man, 1999] which is a much simpler version of Nanna’s Song. Is that going back to what you’ve just said about the basic honesty of a man and guitar and a voice?

Yes, I think it is. When I wrote that song I wrote it how you hear it the second time. When I took it to the studio, they went, ‘Oh God, it’s French! We’ve got to put some accordion on it.’ It was all a kind of musical cliché. Actually that song on that first album probably sold the album. Because I think it was an honest intent. If someone were to study that song I hope they would see it’s not just a song of being in love in Paris. It’s a song of regret that things are coming to a close – though they never did. But that’s the perception of the song at the time. It’s a wistful song that deals with meeting and parting somehow. Are they still together? Do you know what happened?

I’ve got this thing about songs. If you get it straightaway, it’s one kind of song; if it creeps into you, it’s another song; if you return to a song, it’s another. I picked a quote up the other day from Samuel Taylor Coleridge: it’s the poems we go back to, to read again that are the special ones. I would like my songs to be thought of like that. I would like it would be possible to go back to them and find something that you didn’t get the first time.

The exception to that is the ‘big song’ – The Streets of London. It is what it is: it does what it says on the tin: there’s no need to go back to it. And ironically it’s the one that everybody goes back to and keeps talking about. That’s the way it is. Most of my songs aren’t as direct or as straight ahead as that. I like to think there’s nearly always a built-in ‘something else’.

Small print

Unless otherwise stated, all interview material is original and copyright Ken Hunt. If you wish to quote, seek permission. It’s the writer’s way.

For more information and updates about Ralph McTell, go to www.ralphmctell.co.uk